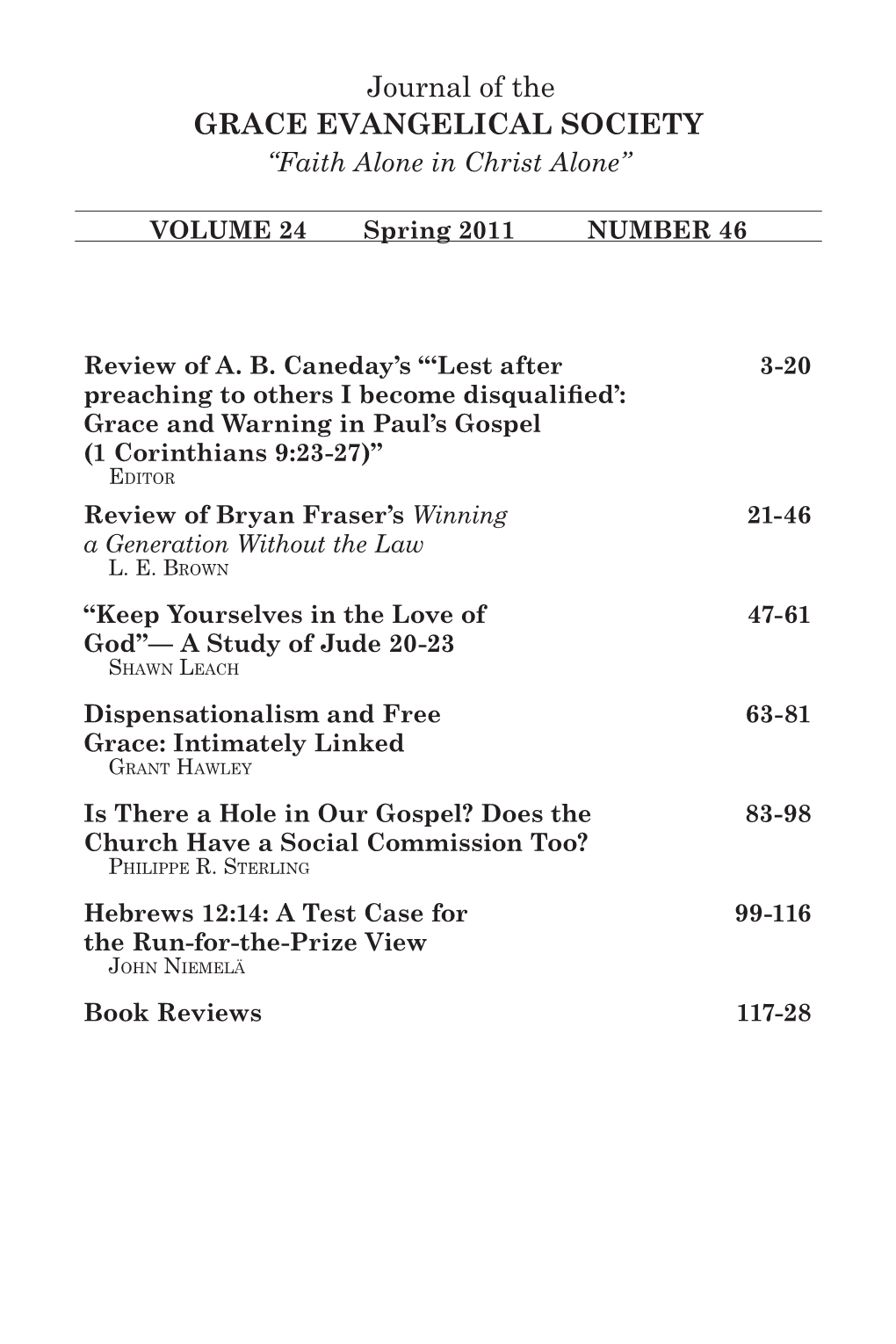

Spring 2011 NUMBER 46

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POSTMODERN OR PROPOSITIONAL? Robert L

TMSJ 18/1 (Spring 2007) 3-21 THE NATURE OF TRUTH: POSTMODERN OR PROPOSITIONAL? Robert L. Thomas Professor of New Testament Ernest R. Sandeen laid a foundation for a contemporary concept of truth that was unique among evangelicals with a high view of Scripture. He proposed that the concept of inerrancy based on a literal method of interpretation was late in coming during the Christian era, having its beginning among the Princeton theologians of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He ruled out their doctrines related to inspiration because they were based on rational thinking which he taught was absent from earlier Christian thought. Subsequent evaluations of Sandeen’s work have disproved his assumption that those doctrines were absent from Christianity prior to the Princeton era. Yet well-known Christian writers have since built on Sandeen’s foundation that excludes rationality and precision from an interpretation of Scripture. The Sandeenists criticize the Princetonians for overreacting in their response to modernism, for their use of literal principles of interpretation, for defining propositional truth derived from the Bible, and for excluding the Holy Spirit’s help in interpretation. All such criticisms have proven to be without foundation. The Princetonians were not without fault, but their utilization of common sense in biblical interpretation was their strong virtue. Unfortunately, even the Journal of the inerrantist Evangelical Theological Society has promoted some of the same errors as Sandeen. The divine element in inspiration is a guarantee of the rationality and precision of Scripture, because God, the ultimate author of Scripture, is quite rational and precise, as proven by Scripture itself. -

Calvinism Or Arminianism? They Have Both Led to Confusion, Division and False Teaching

Is Calvinism or Arminianism Biblical? A Biblical Explanation of the Doctrine of Election. By Cooper P. Abrams, III (*All rights reserved) [Comments from some who read this article] [Frequently Asked Questions About Calvinism] Is Calvinism or Arminianism Biblical? One of the most perplexing problems for the teacher of God's Word is to explain the relationship between the doctrine of election and the doctrine of salvation by grace. These two doctrines are widely debated by conservative Christians who divide themselves into two opposing camps, the "Calvinists" and the "Arminians." To understand the problem let us look at the various positions held, the terms used, a brief history of the matter, and then present a biblical solution that correctly addresses the issue and avoids the unbiblical extremes of both the Calvinists and the Arminians. Introduction to Calvinism John Calvin, the Swiss reformer (1509-1564) a theologian, drafted the system of Soteriology (study of salvation) that bears his name. The term "Calvinism" refers to doctrines and practices that stemmed from the works of John Calvin. The tenants of modern Calvinism are based on the works of Calvin that have been expanded by his followers. These beliefs became the distinguishing characteristics of the Reformed churches and some Baptists. Simply stated, this view claims that God predestined or elected some to be saved and others to be lost. Those elected to salvation are decreed by God to receive salvation and cannot "resist God's grace." However, those that God elected to be lost are born condemned eternally to the Lake of Fie and He will not allow them be saved. -

Autumn 1995 NUMBER 15

Journal of the GRACE EVANGELICAL SOCIETY "Faith Alone in Cbrist Alone" VOLUME 8 Autumn 1995 NUMBER 15 A Dangerous Book or a Faulty Review? A Rejoinder to Robert Vilkin's Critique of A House United? VILLIAM D. \TATKINS 3-23 A Surrejoinder to Villiam D. Vatkins's Rejoinder to My Critique of A House United? ROBERT N. \TILKIN 25-37 The Faith of Demons: James 2;19 JOHN F. HART 39-54 Soteriological Implications of Five-Point Calvinism PHILIP F. CONGDON 55-68 A Voice from the Past: The True Grace of God in Vhich You Stand J. N. DARBY 6e-73 Book Reviews 75-90 Periodical Reviews 9l-95 A Hymn of Grace: Rock of Ages FRANCES A. MOSHER 97-99 Books Received lO1-103 Journal of the GRACE EVANGELICAL SOCIETY Published Semiannuallv bv GES Editor Arthur L. Farstad Associate Editors Production Zane C. Hodges Cathy Beach Robert N. Vilkin Sue Broadwell Mark J. Farstad Manuscripts, periodical and book reviews, and other communi- cations should be addressed to Cathy Beach, GES, P.O. Box 167128, Irving, TX75016-7128. Journal subscriptions, renewals, and changes of address should be sent to the Grace Evangelical Society, P.O. Box 167128, Irving, TX 75016-71,28. Subscription Rates: single copy, $7.50 (U.S.); 1year,$tS.OO; 2 years, $zs.Oo; 3 years, $lf.oo; 4 years, $48.00. Members of GES receive the Journal at no additional charge beyond the membership dues of $ts.OO ($10.00 for active full-time student members). Purpose: The Grace Evangelical Society was formed "to promote the clear proclamation of God's free salvation through faith alone in Christ alone, which is properly correlated with and distinguished from issues related to discipleship." Statement of Faith: "Jesus Christ, God incarnate, paid the full penalty for man's sin when He died on the Cross of Calvary. -

20 Timothy George: Luther Vs

10 Questions: Greg Gilbert 7 / Q & A: Thomas Nettles 15 / Greg Forster: Joy of Calvinism 10 CredoVol. 2, Issue 3 - May 2012 Chosen by Grace 20 TIMOTHY GEORGE: Luther vs. Erasmus 27 PAUL HELM: Calvin vs. Bolsec 36 MATTHEW BARRETT: Unconditional Election 46 BRUCE WARE: Suffering and the Elect 55 FRED ZASPEL: Warfield and Predestination Timothy Paul Jones | KY Director of the Doctor of Education program We are Serious about the Gospel he Southern Seminary Doctor Our Ed.D. will provide a practical yet of Education degree will equip theologically-grounded curriculum that you to serve as a leader in can be completed in 30-months from Christian educational institutions or in anywhere. For more information see the educational ministries of the church. www.sbts.edu/edd Visit us at sbts.edu INTRODUCING the Reformation Commentary on Scripture from InterVarsity Press “ e Reformation Commentary on Scripture is a major publishing event—for those with historical interest in the founding convictions of Protestantism, but even more for those who care about understanding the Bible.” —Mark A. Noll, Francis A. McAnaney Professor of History, University of Notre Dame Ezekiel, Daniel Edited by Carl L. Beckwith Discover fi rsthand the Reformers’ also available innovative readings of the Old Testament prophets Ezekiel and Daniel. Familiar passages like Ezekiel’s vision of the wheels or Galatians, Daniel’s four beasts are revital- Ephesians ized as they take the stage at this Edited by Gerald L. Bray pivotal moment in history. 978-0-8308-2973-6, $50.00 978-0-8308-2962-0, $50.00 scan here for a video introduction to the rcs! For information on how you can subscribe to the Reformation Commentary on Scripture and be the fi rst to receive new volumes, visit ivpress.com/rcsad. -

Contents THEME: Spiritual Leadership Editorial EVANGELICAL REVIEW of THEOLOGY Page 99 Lord Radstock and the St

Contents THEME: Spiritual Leadership Editorial REVIEW OF THEOLOGY EVANGELICAL page 99 Lord Radstock and the St. Petersburg Revival ANDREY P. PUZYNIN page 100 David Livingstone’s Vision Revisited – Christianity, Commerce and Civilisation in the 21st Century SAS CONRADIE page 118 The Missional-Ecclesial Leadership Vision of the Early Church PERRY W.H. SHAW page 131 From ‘Grammatical-historical Exegesis’ to ‘Theological Exegesis’: Five Essential Practices HANK VOSS page 140 The Bible and our Postmodern World 37, NO 2, April 2013 VOLUME Articles and book reviews reflecting BILLY KRISTANTO global evangelical theology for the purpose page 153 of discerning the obedience of faith Bias and Conversion: An Evaluation of Spiritual Transformation BENSON OHIHON IGBOIN page 166 Reviews page 183 Volume 37 No. 2 April 2013 Evangelical Review of Theology GENERAL EDITOR: THOMAS SCHIRRMACHER Articles and book reviews reflecting global evangelical theology for the purpose of discerning the obedience of faith Published by for WORLD EVANGELICAL ALLIANCE Theological Commission Volume 37 No. 2 April 2013 Copyright © 2013 World Evangelical Alliance Theological Commission Dr Thomas Schirrmacher, Germany Dr David Parker, Australia Executive Committee of the WEA Theological Commission Dr Thomas Schirrmacher, Germany, Executive Chair Dr James O. Nkansah, Kenya, Vice-Chair Dr Rosalee V. Ewell, Brasil, Executive Director The articles in the Evangelical Review of Theology reflect the opinions of the authors and reviewers and do not necessarily represent those of the Editor or the Publisher. should be addressed to the Editor Dr Thomas Schirrmacher, Friedrichstrasse 38, 53111 Bonn, Germany. The Editors welcome recommendations of original or published articles or book reviews that relate to forthcoming issues for inclusion in the Review. -

The Calvinism Debate

The Calvinism Debate Updated January 27, 2009 (first published December 12, 2001) (David Cloud, Fundamental Baptist Information Service, http://www.wayoflife.org/database/calvinismdebate.html. Calvinism is a theology that was developed by John Calvin (1509-64) in the sixteenth century. He presented this theology in his Institutes of Christian Religion, which subsequently became the cor- nerstone of Presbyterian and Reformed theology. It is also called TULIP theology. Calvin himself did not use the term TULIP to describe his theology, but it is an accurate, though simplified, repre- sentation of his views, and every standard point of TULIP theology can be found in Calvin’s Insti- tutes. Calvinistic theology was summarized into five points during the debate over the teachings of Jaco- bus Arminius (1560-1609). Arminius studied under Theodore Beza, Calvin’s successor at Geneva, but he rejected Calvinism and taught his non-Calvinist theology in Holland. Arminius’ followers arranged his teaching under the following five points and began to distribute this theology among the Dutch churches in 1610: (1) Free will, or human ability, (2) Conditional election, (3) Universal Redemption, or General Atonement, (4) Resistible Grace, and (5) Insecure Faith. These points were rejected at the state-church Synod of Dort in Holland in 1618-1619 (attended as well by representa- tives from France, Germany, Switzerland, and Britain), and this Synod formulated the “five points of Calvinism” in resistance to Arminianism. Arminius’ followers were thereafter put out of their churches and persecuted by their Calvinist brethren. In the late 18th century, the five points of Calvinism were rearranged under the acronym TULIP as a memory aid. -

The Holy Spirit

Published by Chapel Library 2603 West Wright St. Pensacola, Florida 32505 USA Sending Christ-centered materials from prior centuries worldwide Worldwide: please use the online downloads worldwide without charge. In North America: please write for a printed copy without charge. We do not ask for donations, send promotional mailings, or share the mailing list. The Holy Spirit Arthur W. Pink 1886-1952 Contents 1. The Holy Spirit............................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 2. The Personality of the Holy Spirit.. Error! Bookmark not defined. 3. The Deity of the Holy Spirit........... Error! Bookmark not defined. 4. The Titles of the Holy Spirit........... Error! Bookmark not defined. 5. The Covenant-Offices of the Holy Spirit Error! Bookmark not defined. 6. The Holy Spirit During the Old Testament Ages Error! Bookmark not defined. 7. The Holy Spirit and Christ ............ Error! Bookmark not defined. 8. The Advent of the Spirit................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 9. The Work of the Spirit.................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 10. The Holy Spirit Regenerating......... Error! Bookmark not defined. 11. The Spirit Quickening..................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 12. The Spirit Enlightening .................. Error! Bookmark not defined. 13. The Spirit Convicting ..................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 14. The Spirit Comforting..................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 15. The Spirit Drawing ......................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 16. The Spirit Working Faith................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 17. The Spirit Uniting to Christ............ Error! Bookmark not defined. 18. The Spirit Indwelling...................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 19. The Spirit Teaching ........................ Error! Bookmark not defined. 20. The Spirit Cleansing ....................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 21. The Spirit Leading.......................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 22. -

The Love of God for Humanity1

TMSJ 7/1 (Spring 1996) 7-30 THE LOVE OF GOD FOR HUMANITY1 John F. MacArthur, Jr. President and Professor of Pastoral Ministries John 3:16 declares God's love for the whole world, but in recent times some have insisted that God does not love everyone. The OT and the NT repeatedly indicate that God's love extends to everyone. The immediate context of John 3:16 supports this fact. Further, no grounds exist for questioning God's sincerity in showing mercy to the non-elect. Though difficult for humans to understand, God can love and be the Savior of those whom He does not save. His love for the elect may be somewhat different from that for the non-elect, but His love for the latter is still genuine. God demonstrates His love for all people in four ways: through His common grace, through His compassion, through His admonitions to the lost, and through His gospel offer to them. * * * * * Perhaps you have noticed that someone shows up at almost every major American sporting event, in the center of the television camera's view, holding a sign that usually reads "John 3:16." At the World Series, the sign can normally be spotted right behind home plate. At the Super Bowl, someone holding the sign inevitably has seats between the goalposts. And in the NBA playoffs, the ubiquitous "John 3:16" banner can be seen somewhere in the front-row seats. How these people always manage to get prime seats is a mystery. But someone is always there, often wearing a multicolored wig to call 1The source of this essay is the recently released volume entitled The Love of God (Dallas: Word, 1996). -

LD5655.V856 1985.W567.Pdf (14.36Mb)

CF FX ÜT~EE:'\M¥ A THE OF $$0-- 2.*.7133 3 1 / K . by ‘ ä iaw ¥·Hn=?.m··1.¢ iéichszrzi léi i „x tige __ rxuhmittsarä tu Um Gmuduattc $'6=•;:a,;!7;_·..· aj.? hszztä te.1¢;¤r· rm:} Sixatre ä.i~:£vm·s„5<;·.· ·§m·· dugrsga tm? e-·u=¤;;eärae::1=.er.·:s ttm In partinl ·}ui·§·i!!ms·r•t ¤i· · cat ÜGCYÜPE CFin cL!¢‘I'*‘CU§£.i5! üüd iI'iEät|‘UE;;€.¥_S.?äl E ,-" ¤ ·*= :. ; Ä.J. Ä _ __ _. 2 . 7 4 fg ‘~· f . „Ü ' [.....*:2..;..-.„..„„„.J;.3.-;.:;,1....:;;-.:;;......-..}...1.*-;.. „ "' ;..~.-«~·- ...„>.. ..........„..........„....- l ‘.·..:.J.......-.........4.‘ _ _ _ T. Hunßs-Chmirraan . T, ¥§§1;3~5··;:-ag; , ·" \...«···*‘ 7‘"“ ‘ ’¢.-' ·'·' ·l ‘·____ "'# 4; __ .>.’i§’;.=:... ...:.2; ,....;...-;,....2. .-.„ „.-.,...„.-,.... K /1...... ..@...».; 7.1.. ..1 ‘ g ' ' ·‘ / - ' é Iäsaäävcan.1 E. I '~ I J L. " 4••~•••·•••1n••·•«•\•••\‘;;...-„.•-{-.• , U I .~•.,;„„,.. - ‘~ E ” Nav:N. EuritX?85 · ‘ A1 wcuid like te recngnize the members nf mv dccturai :smmittee= Chairman Dr. Thomas Hunt and cammittee members Ur. Thomas Sherman: Ur. Eiizabeth Struthers Ma|h¤n• Dr. Margaret Eisenhart: and Dr. Norman God!. Esch at {MEW has made inveiuabie cuntributinns ta this researeh experience and to my education. 1 would especially iike tn thank Dr. Hunt for his painstaking supervision at the - writing: Ur. Sherman tor iurcing me to grapnle with difficult issues: and Dr. Maibun for her assistance·in polishing the final manuscript. My appreciatien is extended to all those on the answered A Statt at Appaiachian Bible College who patientiy endless questions and helped me to fänd the materials - that 1 needed. Betty Phillips deserves sseuiai . recognitisn tar her assistance in iocating +i$es.end V . -

Calvinism Debate Copyright 2006 by David W

The Calvinism Debate Copyright 2006 by David W. Cloud This edition December 2020 ISBN: 1-58318-093-1 Published by Way of Life Literature PO Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) - [email protected] www.wayoflife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church 4212 Campbell St. N., London Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 (voice) - 519-652-0056 (fax) [email protected] Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry Contents What We Believe about Salvation ...................................5 Introductory Points ...........................................................9 John Calvin and Process Salvation ...............................21 A Summary of TULIP Teology ...................................25 Calvinism on the March .................................................30 Central Errors of Calvinism ..........................................42 Not all Calvinists the Same ............................................76 Beware of Quick Prayerism ...........................................80 Calvin’s Camels ................................................................83 Calvinism’s Proof Texts Examined .............................114 What about Hyper-Calvinism? ...................................160 A Question for Non-hyper Calvinists ........................164 Hebrews vs. Sovereign Election Teology .................167 Calvinist Standard Version (CSV) ..............................171 “By predestination we mean the eternal decree of God, by which he determined with himself whatever he wished to happen with regard to every man. -

The Forgotten Pink by Rev

1 The Forgotten Pink by Rev. Ronald Hanko Minister in the Protestant Reformed Churches of North America This article was first published in the British Reformed Journal No. 17 for Jan - March 1997 Spurgeon First Forgotten We have deliberately chosen the title of this article in reference to the book, pub- lished by the Banner of Truth Trust and written by Mr. Iain Murray, entitled The Forgotten Spurgeon. In that excellent book Murray accuses the religious world of forgetting that Spurgeon was a Calvinist and shows what an implacable opponent of Arminianism he was. Thus Murray speaks with disapproval of the Kelvedon edition of Spurgeon’s works in which “Arminianism” was removed from some sermons. Murray says, “More serious- ly, ‘Arminianism’has been removed from the text of some of Spurgeon’s Sermons reprint- ed in the Kelvedon edition, though no warning of the abridgement is given to the reader” (The Forgotten Spurgeon, second edition, 1973, p. 52, note)1 . Let us note that Murray’s criticism revolves primarily around the removal of all ref- erences to Arminianism, and the fact that no notice of the removal is given to the reader. That removal is sufficient, in Murray’s opinion, to make the Kelvedon edition of Spurgeon’s sermons an “abridgement.” Pink Pinked To our surprise we learned a number of years ago that the Banner of Truth Trust (hereafter referred to as the Banner), with which Mr. Murray has had the closest possible connections over many years, had done the same thing to Arthur Pink’s important book, The Sovereignty of God. -

Copyright © 2018 Evan Todd Fisher All Rights Reserved. the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary Has Permission to Reproduce A

Copyright © 2018 Evan Todd Fisher All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without limitation, preservation or instruction. STRENGTHEN WHAT REMAINS: THE RHETORICAL SITUATION OF JAMES MONTGOMERY BOICE __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Evan Todd Fisher December 2018 APPROVAL SHEET STRENGTHEN WHAT REMAINS: THE RHETORICAL SITUATION OF JAMES MONTGOMERY BOICE Evan Todd Fisher Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Hershael W. York (Chair) __________________________________________ Robert A. Vogel __________________________________________ Michael A. G. Haykin Date ______________________________ To the memory of James Montgomery Boice A tireless champion for the Word of God TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . vii PREFACE . viii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION . 1 Thesis . 6 Background . 18 Methodology . 22 2. THE RISE OF LIBERALISM IN NORTHERN MAINLINE PRESBYTERIANISM . 26 Fundamentalist-Modernist Controversy . 27 Conclusion . 51 3. STRENGTHENING WHAT REMAINS: BOICE’S STRUGGLE WITH THE UPCUSA . 53 The Rise of Neo-Orthodoxy in Mainline Presbyterianism . 53 Ecumenism and the Confession of 1967 . 55 Boice Begins at Tenth and Disagrees with UPCUSA . 61 Working for Change from Within . 76 4. MENTORS THAT SHAPED THE LIFE AND MINISTRY OF JAMES BOICE . 93 Donald Grey Barnhouse . 94 Harold John Ockenga . 99 Robert J. Lamont . 105 iv Chapter Page John Gerstner . 109 Conclusion . 114 5. PROCLAMATION FOR REFORMATION: SERMONS AND WRITINGS OF JAMES BOICE . 116 Strategic Sermons . 116 Genesis . 119 The Gospel of John .