Download The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Ball! One of the Most Recognizable Stars on the U.S

TVhome The Daily Home June 7 - 13, 2015 On the Ball! One of the most recognizable stars on the U.S. Women’s World Cup roster, Hope Solo tends the goal as the U.S. 000208858R1 Women’s National Team takes on Sweden in the “2015 FIFA Women’s World Cup,” airing Friday at 7 p.m. on FOX. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., June 7, 2015 — Sat., June 13, 2015 DISH AT&T CABLE DIRECTV CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA SPORTS BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING 5 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 Championship Super Regionals: Drag Racing Site 7, Game 2 (Live) WCIQ 7 10 4 WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Monday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 8 p.m. ESPN2 Toyota NHRA Sum- 12 p.m. ESPN2 2015 NCAA Baseball WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 mernationals from Old Bridge Championship Super Regionals Township Race. -

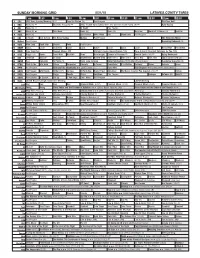

Sunday Morning Grid 5/31/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/31/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å 2015 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Auto Racing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å World of X Games (N) IndyCar 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program The Simpsons Movie 13 MyNet Paid Program Becoming Redwood (R) 18 KSCI Man Land Rock Star Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Easy Yoga Pain Deepak Chopra MD JJ Virgin’s Sugar Impact Secret (TVG) Suze Orman’s Financial Solutions for You (TVG) 28 KCET Raggs Pets. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Echoes of Creation Å Sacred Earth (TVG) Å Aging Backwards 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Al Punto (N) Hotel Todo Incluido Duro Pero Seguro (1978) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Alvin and the Chipmunks ›› (2007) Jason Lee. -

Wild’ Evaluation Between 6 and 9Years of Age

FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:05 PM Residential&Commercial Sales and Rentals tvspotlight Vadala Real Proudly Serving Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Cape Ann Since 1975 Estate • For the week of July 11 - 17, 2015 • 1 x 3” Massachusetts Certified Appraisers 978-281-1111 VadalaRealEstate.com 9-DDr. OsmanBabsonRd. Into the Gloucester,MA PEDIATRIC ORTHODONTICS Pediatric Orthodontics.Orthodontic care formanychildren can be made easier if the patient starts fortheir first orthodontic ‘Wild’ evaluation between 6 and 9years of age. Some complicated skeletal and dental problems can be treated much more efficiently if treated early. Early dental intervention including dental sealants,topical fluoride application, and minor restorativetreatment is much more beneficial to patients in the 2-6age level. Parents: Please makesure your child gets to the dentist at an early age (1-2 years of age) and makesure an orthodontic evaluation is done before age 9. Bear Grylls hosts Complimentarysecond opinion foryour “Running Wild with child: CallDr.our officeJ.H.978-283-9020 Ahlin Most Bear Grylls” insurance plans 1accepted. x 4” CREATING HAPPINESS ONE SMILE AT ATIME •Dental Bleaching included forall orthodontic & cosmetic dental patients. •100% reduction in all orthodontic fees for families with aparent serving in acombat zone. Call Jane: 978-283-9020 foracomplimentaryorthodontic consultation or 2nd opinion J.H. Ahlin, DDS •One EssexAvenue Intersection of Routes 127 and 133 Gloucester,MA01930 www.gloucesterorthodontics.com Let ABCkeep you safe at home this Summer Home Healthcare® ABC Home Healthland Profess2 x 3"ionals Local family-owned home care agency specializing in elderly and chronic care 978-281-1001 www.abchhp.com FINAL-1 Sun, Jul 5, 2015 3:23:06 PM 2 • Gloucester Daily Times • July 11 - 17, 2015 Adventure awaits Eight celebrities join Bear Grylls for the adventure of a lifetime By Jacqueline Spendlove TV Media f you’ve ever been camping, you know there’s more to the Ifun of it than getting out of the city and spending a few days surrounded by nature. -

Sweet Fruits of Innovation How Are Inventive Alumni Improving Our Lives?

58559_Cover_u2.qxd 3/31/09 4:34 PM Page 3 spring 2009 WHEATON Sweet Fruits of Innovation How are inventive alumni improving our lives? Inside: Student DNA Research • Senior Art Show • The Promise Report 58559_ ifc-13_u1.qxd 3/31/09 4:30 PM Page c2 Wheaton College exists to help build the church and improve society worldwide by promoting the development of whole and effective Christians through excellence in programs of Christian higher education. This mission expresses our commitment to do all things “For Christ and His Kingdom.” VOLUME 12 ISSUE 2 8 SPRING 2009 ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 32 A Word with Alumni 2 Letters From the President of the Alumni Association 4 News 33 Wheaton Alumni Association News 10 Sports Association news and events 27 The Promise Report 38 Alumni Class News An update on The Promise of Wheaton campaign 58 Authors Books by Wheaton’s faculty; thoughts from published Cover photo: Dr. David Bedford ’73 rates apples in the apple alumnus Dr. Douglas Sweeney ’87 breeding orchard at the University of Minnesota, where he is a research scientist. His Honeycrisp apple won accolades for 60 Readings its flavor and texture. A 1935 alumnus writes about the Great Depression Photo by Dave Hansen, University of Minnesota 62 Faculty Voice Dr. Jennifer Powell McNutt on providence and history Inside photos: Michael Hudson ’89, pages 7, 10-11, 50, 57, 62, 64, 66; Ellen Rising Morris, page 3; 63 Student Profile Les Barker and Craig Taylor, pages 4, 30-31. A student sings with a world-class opera 64 Wheaton in the World Dr. -

Gaudenz Domenig

Gaudenz DOMENIG * Land of the Gods Beyond the Boundary Ritual Landtaking and the Horizontal World View** 1. Introduction The idea that land to be taken into possession for dwelling or agriculture is already inhabited by beings of another kind may be one the oldest beliefs that in the course of history have conditioned religious attitudes towards space. Where the raising of a building, the founding of a settlement or city, or the clearing of a wilderness for cultivation was accompanied by ritual, one of the ritual acts usually was the exorcising of local beings supposed to have been dwelling there before. It is often assumed that this particular ritual act served the sole purpose of driving the local spirits out of the new human domain. Consequently, the result of the ritual performance is commonly believed to have been a situation where the castaways were thought to carry on beyond the land’s boundary, in an outer space that would surround the occupied land as a kind of “chaos.” Mircea Eliade has expressed this idea as follows: One of the characteristics of traditional societies is the opposition they take for granted between the territory they inhabit and the unknown and indeterminate space that surrounds it. Their territory is the “world” (more precisely, “our world”), the cosmos; the rest is no longer cosmos but a kind of “other world,” a foreign, chaotic space inhabited by ghosts, demons, and “foreigners” (who are assimilated to the demons and the souls of the dead). (Eliade 1987: 29) * MSc ETH (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology), Zürich. -

14.Az:“Energy (Electricity & Gas) Sector Performance Assessment And

14.AZ:“ENERGY (ELECTRICITY & GAS) SECTOR PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT AND IMPROVEMENT UNDER THE REGULATORY PERSPECTIVE” INOGATE Technical Secretariat (ITS) and Integrated Programme in support of the Baku Initiative and the Eastern Partnership energy objectives Contract No 2011/278827 A project within the INOGATE Programme Implemented by: Ramboll Denmark A/S (lead partner) EIR Development Partners Ltd. The British Standards Institution LDK Consultants S.A. MVV decon GmbH ICF International Statistics Denmark Energy Institute Hrvoje Požar i Project Title: “ENERGY (ELECTRICITY & GAS) SECTOR PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT AND IMPROVEMENT UNDER THE REGULATORY PERSPECTIVE” Contract No: 2011/278827 Country: Azerbaijan Project Office EC Contractor INOGATE Technical Secretariat Kiev Ramboll Denmark A/S Name Kudriavska 26/28 Hannemanns Allé 53, Address 04053 Kiev – Ukraine 2300 Copenhagen S Denmark +380 44 230 2754 +45 51 61 85 91 Tel. Number +380 44 230 2753 +45 51 61 10 01 Fax Number e-mail Contact Person Signatures Authors: Non Key Expert Team CONTRACTING AUTHORITIES Signature Date EC Programme Ms Viola Calabrese Manager Document title ENERGY (ELECTRICITY & GAS) SECTOR PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENT AND IMPROVEMENT UNDER THE REGULATORY PERSPECTIVE Prepared by Konstantinos Perrakis, Katerina Sardi, Nikos Tourlis and Zaur Mamadov Checked by Nikos Tsakalidis Date January 2015, March 2015 ii Acronyms ACER Agency for the cooperation of Energy Regulators AGI Above Ground Installation AHEF Ad-Hoc Expert Facility BETTA British Electricity Trading and Transmission Arrangements -

Special Interest Zenders

TV Uitzendschema - Special Interest zenders Periode 22-8-2016 t/m 18-9-2016 Doelgroep 25-59 jaar Dag Datum Tijd Spotlengte Zender Progn. grp's P Programma voor Programma na ma 22-08-16 08:10 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment ma 22-08-16 08:50 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 09:20 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 09:40 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 10:14 20+5 TLC 0,3 my 600lb life my 600lb life ma 22-08-16 11:20 20+5 Xite 0,0 after school after school ma 22-08-16 11:30 20+5 SlamTV 0,0 most wanted most wanted ma 22-08-16 11:47 20+5 TLC 0,1 gypsy sisters gypsy sisters ma 22-08-16 11:55 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment ma 22-08-16 12:25 5+20 History 0,0 storage wars storage wars ma 22-08-16 12:31 20+5 RTL Lounge 0,0 wonderland wonderland ma 22-08-16 12:55 20+5 Crime Inv 0,0 crimes that shook britain 2 crimes that shook britain 2 ma 22-08-16 13:00 20+5 SlamTV 0,0 slam!non-stop slam!non-stop ma 22-08-16 13:01 20+5 Comedy 0,0 bobs burgers bobs burgers ma 22-08-16 13:08 20+5 Crime Inv 0,0 fatal vows fatal vows ma 22-08-16 13:12 20+5 MTV 0,0 made made ma 22-08-16 13:23 20+5 Comedy 0,0 american dad american dad ma 22-08-16 13:56 20+5 Crime Inv 0,0 fatal vows fatal vows ma 22-08-16 14:50 20+5 Xite 0,0 standaard standaard ma 22-08-16 15:37 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment ma 22-08-16 15:50 20+5 Xite 0,0 standaard standaard ma 22-08-16 16:44 20+5 History 0,1 pawn stars uk 0:5hr pawn stars uk 0:5hr ma 22-08-16 17:09 20+5 E! 0,0 e! entertainment e! entertainment -

D.C. CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Jeffrey Dewitt Attachment A

Attachment A D.C. CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Jeffrey DeWitt Executive Assistant Acting Executive Director CIO Michelle Johnson Ridgely Bennett Alok Chadda TE: 4 Director of Information Technology Special Assistant Chief Operating Officer Gordon Wong Jennifer Thomas Tracey Cohen FTE: 14 Director, Sports Wagering Oversight & Chief of Compliance & Director of Resource Agency Fiscal Officer Enforcement Management Regulation Craig Lindsey Derrica Wilson Gwen Washington Peter Alvarado FTE: 11 FTE: 11 FTE: 10 FTE: 13.5 Director of Sales Arthur Page FTE: 10 Director of Communications and Marketing FY 2021 Approved Nicole Jordan Budgeted Positions FTE: 15 Total FTEs: 88.5 1 Attachment A Office of Executive Direction FTE: 4 Acting Executive Director Executive Assistant Ridgely Bennett Michelle Johnson 1015 1015 Special Assistant Chief Operating Officer Jennifer Thomas Tracey Cohen 1015 1015 2 Attachment A Security and Licensing FTE: 10 Department Chief Compliance & Enforcement Staff Assistant Derrica Wilson Shameka Bryant 1075 1075 Program Specialist Investigator Russell Bruce Scott Miller 6500 1075 Program Specialist Sarita Curtis Investigator 6500 Edwardo Jackson 1075 Program Specialist Keisha Staples 6500 Systems and Compliance Program Specialist Investigator Niki Mathis Ethan Murphy 6500 1075 Program Specialist Matthew Pinder 6500 3 Attachment A Office of Resources Management FTE: 13.5 Resource Management Director of Resource Management Coordinator Gwen Washington 1010 Dionne Bryant 1010 Chief of Customer Service Chief of Support Services Michael Morton Jonah Ray 1010 Senior Lottery Draw 1030 Specialist Customer Service Anthony Edwards Specialist 6400 Support Services Specialist Grant Jackson Wayne Carrington 1010 1030 Customer Service Lottery Draw Specialist Specialist Juanita Burns (PT) 6400 Support Services Cheryl Malone Specialist 1010 Charles Butler, Jr. -

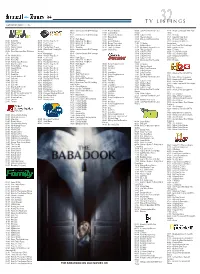

TV Listings SATURDAY, MAY 27, 2017

TV listings SATURDAY, MAY 27, 2017 00:50 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 17:25 Double Teamed 09:00 Jake And The Never Land 12:25 Hollywood Medium With Tyler Witch 19:00 Star Darlings Pirates Henry 01:15 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 19:05 Stuck In The Middle 09:30 Sofia The First 13:15 E! News Witch 19:30 Bizaardvark 10:00 The Lion Guard 13:45 Celebrity Style Story 01:40 Hank Zipzer 19:55 Bunkʼd 10:30 Mickey And The Roadster 14:15 E! News: Daily Pop 00:45 Bondi Vet 00:30 How Do They Do It? 02:05 Binny And The Ghost 20:20 Elena Of Avalor Racers 15:10 Keeping Up With The 01:40 Wildest Africa 00:55 Food Factory 02:30 Binny And The Ghost 20:45 Disney The Lodge 11:00 PJ Masks Kardashians 02:35 Tanked 01:20 Mythbusters 02:55 Hank Zipzer 21:10 Girl Meets World 11:25 Goldie & Bear 16:10 Live From The Red Carpet 03:25 Wildest Islands 02:10 The Big Brain Theory 03:15 The Hive 21:35 Thatʼs So Raven 11:55 My Friends Tigger & Pooh 18:00 Fashion Police 04:15 Cats 101 03:00 What Could Possibly Go 03:20 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 22:00 Shake It Up 12:20 The Lion Guard 19:00 E! News 05:02 River Monsters (Best Of Series Wrong? Witch 12:50 Sofia The First 20:00 Second Wives Club 1-5) 03:48 Mythbusters 03:45 Sabrina Secrets Of A Teenage 13:20 Sofia The First 21:00 Second Wives Club 05:49 Wildest Africa 04:36 How Do They Do It? Witch 13:45 Sofia The First 22:00 Keeping Up With The 06:36 Going Ape 05:00 Food Factory 04:10 Hank Zipzer 14:10 Sofia The First Kardashians 07:00 Going Ape 05:24 Mythbusters 04:35 Binny And The Ghost 14:40 Mickey And The Roadster 23:00 -

How Long Distance Foot Travel Shaped Views of Nature and Society in Early Modern America Brian Christopher Hurley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2016 Walking in American History: How Long Distance Foot Travel Shaped Views of Nature and Society in Early Modern America Brian Christopher Hurley University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Environmental Studies Commons, Other American Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hurley, Brian Christopher, "Walking in American History: How Long Distance Foot Travel Shaped Views of Nature and Society in Early Modern America" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 1530. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1530 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Walking in American History: How Long Distance Foot Travel Shaped Views of Nature and Society in Early Modern America A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment Of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Brian C. Hurley Colby College Bachelor of Arts in History and Religious Studies, 2003 May 2016 University of Arkansas This dissertation is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. ____________________________________________________ Dr. Elliott West Dissertation Director _____________________________________________________ Dr. Michael Pierce -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Japanese Folk Tale

The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Copublished with Asian Folklore Studies YANAGITA KUNIO (1875 -1962) The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale Translated and Edited by FANNY HAGIN MAYER INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS Bloomington This volume is a translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai. Tokyo: Nihon Hoso Shuppan Kyokai, 1948. This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by ASIAN FOLKLORE STUDIES, Nanzan University, Nagoya, japan. © All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nihon mukashibanashi meii. English. The Yanagita Kunio guide to the japanese folk tale. "Translation of Nihon mukashibanashi meii, compiled under the supervision of Yanagita Kunio and edited by Nihon Hoso Kyokai." T.p. verso. "This book has been produced from camera-ready copy provided by Asian Folklore Studies, Nanzan University, Nagoya,japan."-T.p. verso. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Tales-japan-History and criticism. I. Yanagita, Kunio, 1875-1962. II. Mayer, Fanny Hagin, 1899- III. Nihon Hoso Kyokai. IV. Title. GR340.N52213 1986 398.2'0952 85-45291 ISBN 0-253-36812-X 2 3 4 5 90 89 88 87 86 Contents Preface vii Translator's Notes xiv Acknowledgements xvii About Folk Tales by Yanagita Kunio xix PART ONE Folk Tales in Complete Form Chapter 1.