A Checklist of the Cave Fauna of Oklahoma: Amphibia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spotted Chorus Frog

This Article From Reptile & Amphibian Profiles From February, 2005 The Cross Timbers Herpetologist Newsletter of the Dallas-Fort Worth Herpetological Society Dallas-Fort Worth Herpetological Society is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organiza- tion whose mission is: To promote understanding, appreciation, and conservation Spotted Chorus Frog ( Pseudacris clarkii ) of reptiles and amphibians, to encourage respect for their By Michael Smith habitats, and to foster respon- Texas winters can be cold, with biting loud for a frog of such small size. As the frogs sible captive care. winds and the occasional ice storm. But Texas brace against prairie grasses in the shallow wa- winters are often like the tiny north Texas ter, the throats of the males expand into an air- towns of Santo or Venus – you see them com- filled sac and call “wrret…wrret…wrret” to All articles and photos remain ing down the road, but if you blink twice nearby females. under the copyright of the au- you’ve missed them. And so, by February we Spotted chorus frogs are among the small thor and photographer. This often have sunny days where a naturalist’s and easily overlooked herps of our area, but publication may be redistributed thoughts turn to springtime. Those earliest they are beautiful animals with interesting life- in its original form, but to use the sunny days remind us that life and color will article or photos, please contact: return to the fields and woods. styles. [email protected] In late February or early March, spring Classification rains begin, and water collects in low places. -

The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-Dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus Spp

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2005 The aN tural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia Michael Steven Osbourn Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Osbourn, Michael Steven, "The aN tural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia" (2005). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 735. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia. Thesis submitted to The Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Science Biological Sciences By Michael Steven Osbourn Thomas K. Pauley, Committee Chairperson Daniel K. Evans, PhD Thomas G. Jones, PhD Marshall University May 2005 Abstract The Natural History, Distribution, and Phenotypic Variation of Cave-dwelling Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus spp. Cope (Plethodontidae), in West Virginia. Michael S. Osbourn There are over 4000 documented caves in West Virginia, potentially providing refuge and habitat for a diversity of amphibians and reptiles. Spring Salamanders, Gyrinophilus porphyriticus, are among the most frequently encountered amphibians in caves. Surveys of 25 caves provided expanded distribution records and insight into ecology and diet of G. -

Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts

2 0 1 5 – 2 0 2 5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts Appendix 1.4C-Amphibians Amphibian Species of Greatest Conservation Need Maps: Physiographic Provinces and HUC Watersheds Species Accounts (Click species name below or bookmark to navigate to species account) AMPHIBIANS Eastern Hellbender Northern Ravine Salamander Mountain Chorus Frog Mudpuppy Eastern Mud Salamander Upland Chorus Frog Jefferson Salamander Eastern Spadefoot New Jersey Chorus Frog Blue-spotted Salamander Fowler’s Toad Western Chorus Frog Marbled Salamander Northern Cricket Frog Northern Leopard Frog Green Salamander Cope’s Gray Treefrog Southern Leopard Frog The following Physiographic Province and HUC Watershed maps are presented here for reference with conservation actions identified in the species accounts. Species account authors identified appropriate Physiographic Provinces or HUC Watershed (Level 4, 6, 8, 10, or statewide) for specific conservation actions to address identified threats. HUC watersheds used in this document were developed from the Watershed Boundary Dataset, a joint project of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Physiographic Provinces Central Lowlands Appalachian Plateaus New England Ridge and Valley Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain Appalachian Plateaus Central Lowlands Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain New England Ridge and Valley 675| Appendix 1.4 Amphibians Lake Erie Pennsylvania HUC4 and HUC6 Watersheds Eastern Lake Erie -

<I>Salamandra Salamandra</I>

International Journal of Speleology 46 (3) 321-329 Tampa, FL (USA) September 2017 Available online at scholarcommons.usf.edu/ijs International Journal of Speleology Off icial Journal of Union Internationale de Spéléologie Subterranean systems provide a suitable overwintering habitat for Salamandra salamandra Monika Balogová1*, Dušan Jelić2, Michaela Kyselová1, and Marcel Uhrin1,3 1Institute of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, P. J. Šafárik University, Šrobárova 2, 041 54 Košice, Slovakia 2Croatian Institute for Biodiversity, Lipovac I., br. 7, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia 3Department of Forest Protection and Wildlife Management, Faculty of Forestry and Wood Sciences, Czech University of Life Sciences, Kamýcká 1176, 165 21 Praha, Czech Republic Abstract: The fire salamander (Salamandra salamandra) has been repeatedly noted to occur in natural and artificial subterranean systems. Despite the obvious connection of this species with underground shelters, their level of dependence and importance to the species is still not fully understood. In this study, we carried out long-term monitoring based on the capture-mark- recapture method in two wintering populations aggregated in extensive underground habitats. Using the POPAN model we found the population size in a natural shelter to be more than twice that of an artificial underground shelter. Survival and recapture probabilities calculated using the Cormack-Jolly-Seber model were very constant over time, with higher survival values in males than in females and juveniles, though in terms of recapture probability, the opposite situation was recorded. In addition, survival probability obtained from Cormack-Jolly-Seber model was higher than survival from POPAN model. The observed bigger population size and the lower recapture rate in the natural cave was probably a reflection of habitat complexity. -

Protozoan, Helminth, and Arthropod Parasites of the Sported Chorus Frog, Pseudacris Clarkii (Anura: Hylidae), from North-Central Texas

J. Helminthol. Soc. Wash. 58(1), 1991, pp. 51-56 Protozoan, Helminth, and Arthropod Parasites of the Sported Chorus Frog, Pseudacris clarkii (Anura: Hylidae), from North-central Texas CHRIS T. MCALLISTER Renal-Metabolic Lab (151-G), Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, 4500 S. Lancaster Road, Dallas, Texas 75216 ABSTRACT: Thirty-nine juvenile and adult spotted chorus frogs, Pseudacris clarkii, were collected from 3 counties of north-central Texas and examined for parasites. Thirty-three (85%) of the P. clarkii were found to be infected with 1 or more parasites, including Hexamita intestinalis Dujardin, 1841, Tritrichomonas augusta Alexeieff, 1911, Opalina sp. Purkinje and Valentin, 1840, Nyctotherus cordiformis Ehrenberg, 1838, Myxidium serotinum Kudo and Sprague, 1940, Cylindrotaenia americana Jewell, 1916, Cosmocercoides variabilis (Harwood, 1930) Travassos, 1931, and Hannemania sp. Oudemans, 1911. All represent new host records for the respective parasites. In addition, a summary of the 36 species of amphibians and reptiles reported to be hosts of Cylin- drotaenia americana is presented. KEY WORDS: Anura, Cosmocercoides variabilis, Cylindrotaenia americana, Hannemania sp., Hexamita in- testinalis, Hylidae, intensity, Myxidium serotinum, Nyctotherus cordiformis, Opalina sp., prevalence, Pseudacris clarkii, spotted chorus frog, survey, Tritrichomonas augusta. The spotted chorus frog, Pseudacris clarkii ported to the laboratory where they were killed with (Baird, 1854), is a small, secretive, hylid anuran an overdose of Nembutal®. Necropsy and parasite techniques are identical to the methods of McAllister that ranges from north-central Kansas south- (1987) and McAllister and Upton (1987a, b), except ward through central Oklahoma and Texas to that cestodes were stained with Semichon's acetocar- northeastern Tamaulipas, Mexico (Conant, mine and larval chiggers were fixed in situ with 10% 1975). -

Chris Harper Private Lands Biologist U.S

Chris Harper Private Lands Biologist U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Austin Texas Ecological Services Office 512-490-0057 x 245 [email protected] http://www.fws.gov/partners/ U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service The Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program in Texas Voluntary Habitat Restoration on Private Lands • The Mission of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: working with others to conserve, protect and enhance fish, wildlife, and plants and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people Federal Trust Species • The term “Federal trust species” means migratory birds, threatened species, endangered species, interjurisdictional fish, marine mammals, and other species of concern. • “Partners for Fish and Wildlife Act” (2006) • To authorize the Secretary of the Interior to provide technical and financial assistance to private landowners to restore, enhance, and manage private land to improve fish and wildlife habitats through the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program. Habitat Restoration & Enhancement • Prescribed fire • Brush thinning • Grazing management • Tree planting • Native seed planting • Invasive species control • In-stream restoration • “Fish passage” • Wetlands Fire as a Driver of Vegetation Change • Climate X Fire Interactions • Climate X Grazing Interactions • Climate X Grazing X Fire • Historic effects • Time lags • Time functions • Climate-fuels-fire relationships • Fire regimes • Restoring fire-adapted ecosystems Woody encroachment Austin PFW • Houston Toad – Pine/oak savanna/woodlands • Southern Edwards Plateau -

2005 MO Cave Comm.Pdf

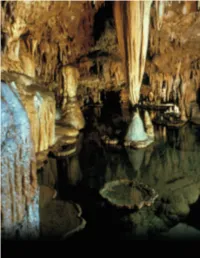

Caves and Karst CAVES AND KARST by William R. Elliott, Missouri Department of Conservation, and David C. Ashley, Missouri Western State College, St. Joseph C A V E S are an important part of the Missouri landscape. Caves are defined as natural openings in the surface of the earth large enough for a person to explore beyond the reach of daylight (Weaver and Johnson 1980). However, this definition does not diminish the importance of inaccessible microcaverns that harbor a myriad of small animal species. Unlike other terrestrial natural communities, animals dominate caves with more than 900 species recorded. Cave communities are closely related to soil and groundwater communities, and these types frequently overlap. However, caves harbor distinctive species and communi- ties not found in microcaverns in the soil and rock. Caves also provide important shelter for many common species needing protection from drought, cold and predators. Missouri caves are solution or collapse features formed in soluble dolomite or lime- stone rocks, although a few are found in sandstone or igneous rocks (Unklesbay and Vineyard 1992). Missouri caves are most numerous in terrain known as karst (figure 30), where the topography is formed by the dissolution of rock and is characterized by surface solution features. These include subterranean drainages, caves, sinkholes, springs, losing streams, dry valleys and hollows, natural bridges, arches and related fea- Figure 30. Karst block diagram (MDC diagram by Mark Raithel) tures (Rea 1992). Missouri is sometimes called “The Cave State.” The Mis- souri Speleological Survey lists about 5,800 known caves in Missouri, based on files maintained cooperatively with the Mis- souri Department of Natural Resources and the Missouri Department of Con- servation. -

Baseline Population Inventory of Amphibians on the Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge and Screening for the Amphibian Disease Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis

Baseline Population Inventory of Amphibians on the Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge and Screening for the Amphibian Disease Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis This study was funded by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Southeast Region Inventory and Monitoring Network FY 2012 September 2013 Gregory Scull1 Chester Figiel1 Mark Meade2 Richard Watkins2 1U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 2Jacksonville State University, Jacksonville, Alabama The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Introduction: Amphibians are facing worldwide population declines, range contractions, and species extinction. Within the last 30 years, over 200 species have become extinct and close to one-third of the world’s amphibians are imperiled (IUCN, 2010). A recent trend analysis indicates that amphibian decline may be even more widespread and severe than previously realized and includes species for which there has been little conservation concern or assessment focus in the past (Adams et al. 2013). Factors such as invasive species, disease, changes in land use, climate change effects and the interactions of these factors all form current hypotheses that attempt to explain this dilemma (McCallum, 2007). This is alarming considering that the Southeast contains the highest level of amphibian diversity in the United States. It is imperative that we obtain and maintain current information on amphibian communities inhabiting our public lands so that we can adaptively manage resources for their long-term survival. Although a number of causes appear related to amphibian declines in recent years, one of the leading factors is the infectious disease known as chytridiomycosis. -

Standard Common and Current Scientific Names for North American Amphibians, Turtles, Reptiles & Crocodilians

STANDARD COMMON AND CURRENT SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR NORTH AMERICAN AMPHIBIANS, TURTLES, REPTILES & CROCODILIANS Sixth Edition Joseph T. Collins TraVis W. TAGGart The Center for North American Herpetology THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY www.cnah.org Joseph T. Collins, Director The Center for North American Herpetology 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 (785) 393-4757 Single copies of this publication are available gratis from The Center for North American Herpetology, 1502 Medinah Circle, Lawrence, Kansas 66047 USA; within the United States and Canada, please send a self-addressed 7x10-inch manila envelope with sufficient U.S. first class postage affixed for four ounces. Individuals outside the United States and Canada should contact CNAH via email before requesting a copy. A list of previous editions of this title is printed on the inside back cover. THE CEN T ER FOR NOR T H AMERI ca N HERPE T OLOGY BO A RD OF DIRE ct ORS Joseph T. Collins Suzanne L. Collins Kansas Biological Survey The Center for The University of Kansas North American Herpetology 2021 Constant Avenue 1502 Medinah Circle Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Lawrence, Kansas 66047 Kelly J. Irwin James L. Knight Arkansas Game & Fish South Carolina Commission State Museum 915 East Sevier Street P. O. Box 100107 Benton, Arkansas 72015 Columbia, South Carolina 29202 Walter E. Meshaka, Jr. Robert Powell Section of Zoology Department of Biology State Museum of Pennsylvania Avila University 300 North Street 11901 Wornall Road Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 Kansas City, Missouri 64145 Travis W. Taggart Sternberg Museum of Natural History Fort Hays State University 3000 Sternberg Drive Hays, Kansas 67601 Front cover images of an Eastern Collared Lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) and Cajun Chorus Frog (Pseudacris fouquettei) by Suzanne L. -

H:\Ken\Salamander\SALAMANDERS W-Cover & Toc.Wpd

Table of Contents I. Introduction ........................................................1 II. Species Accounts ....................................................1 A. Cave Salamander, Eurycea lucifuga Rafinesque ......................1 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................1 2. Historical and Current Distribution ...........................1 3. Species Associations .....................................2 4. Population Sizes and Abundance ............................2 5. Reproduction ...........................................3 6. Food and Feeding Requirements ............................3 B. Many Ribbed Salamander, Eurycea multiplicata geiseogaster ...........3 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................3 2. Life History and Ecological Information ........................3 C. Grotto Salamander, Typlotriton spealaeus Stejneger ...................4 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................4 2. Life History Information and Habitats .........................4 D. Long-tailed Salamander Eurycea longicauda melanopleura Cope ........5 1. Taxonomy and Description .................................5 2. Historical and Current Distribution ...........................5 3. Life History Information ...................................6 III. Ownership of Species Habitats ..........................................6 IV. Potential Threats to Species or Their Habitats ...............................6 V. Protective Laws .....................................................7 A. Federal .....................................................7 -

Obligate Salamander

DOI: 10.1111/jbi.13047 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Hydrologic and geologic history of the Ozark Plateau drive phylogenomic patterns in a cave-obligate salamander John G. Phillips1 | Dante B. Fenolio2 | Sarah L. Emel1,3 | Ronald M. Bonett1 1Department of Biological Sciences, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK, USA Abstract 2Department of Conservation and Research, Aim: Habitat specialization can constrain patterns of dispersal and drive allopatric San Antonio Zoo, San Antonio, TX, USA speciation in organisms with limited dispersal ability. Herein, we tested biogeo- 3Department of Biology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA graphic patterns and dispersal in a salamander with surface-dwelling larvae and obli- gate cave-dwelling adults. Correspondence John G. Phillips, Department of Biological Location: Ozark Plateau, eastern North America. Sciences, University of Tulsa, Tulsa, OK, Methods: A population-level phylogeny of grotto salamanders (Eurycea spelaea com- USA. Current Email: [email protected] plex) was reconstructed using mitochondrial (mtDNA) and multi-locus nuclear DNA (nucDNA), primarily derived from anchored hybrid enrichment (AHE). We tested Funding information Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Grant - patterns of molecular variance among populations and associations between genetic American Museum of Natural History; distance and geographic features. University of Tulsa, Grant/Award Number: 20-2-1211607-53600; Oklahoma Results: Divergence time estimates suggest rapid formation of three major lineages Department of Wildlife Conservation, Grant/ in the Middle Miocene. Contemporary gene flow among divergent lineages appears Award Number: E-22-18 and E22-20; National Science Foundation, Grant/Award negligible, and mtDNA suggests that most populations are isolated. There is a signif- Number: DEB 1050322; Oklahoma icant association between phylogenetic distance and palaeodrainages, contemporary NSF-EPSCoR Program, Grant/Award Number: IIA-1301789 drainages and sub-plateaus of the Ozarks, as all features explain a proportion of genetic variation. -

Amphibians and Reptiles Of

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Amphibians and Reptiles of Aransas National Wildlife Refuge Abundance Common Name Abundance Common Name Abundance C Common; suitable habitat is available, Scientific Name Scientific Name should not be missed during appropriate season. Toads and Frogs Texas Tortoise R Couch’s Spadefoot C Gopherus berlandieri U Uncommon; present in moderate Scaphiopus couchi Guadalupe Spiny Soft-shelled Turtle R numbers (often due to low availability Hurter’s Spadefoot C Trionyx spiniferus guadalupensis of suitable habitat); not seen every Scaphiopus hurteri Loggerhead O visit during season Blanchard’s Cricket Frog U Caretta caretta Acris crepitans blanchardi Atlantic Green Turtle O O Occasional; present, observed only Green Tree Frog C Chelonia mydas mydas a few times per season; also includes Hyla cinerea Atlantic Hawksbill O those species which do not occur year, Squirrel Tree Frog U Eretmochelys imbricata imbricata while in some years may be Hyla squirella Atlantic Ridley(Kemp’s Ridley) O fairly common. Spotted Chorus Frog U Lepidocheyls kempi Pseudacris clarki Leatherback R R Rare; observed only every 1 to 5 Strecker’s Chorus Frog U Dermochelys coriacea years; records for species at Aransas Pseudacris streckeri are sporadic and few. Texas Toad R Lizards Bufo speciosus Mediterranean Gecko C Introduction Gulf Coast Toad C Hemidactylus turcicus turcicus Amphibians have moist, glandular skins, Bufo valliceps valliceps Keeled Earless Lizard R and their toes are devoid of claws. Their Bullfrog C Holbrookia propinqua propinqua young pass through a larval, usually Rana catesbeiana Texas Horned Lizard R aquatic, stage before they metamorphose Southern Leopard Frog C Phrynosoma cornutum into the adult form.