Snake Bites 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freshwater Fishes

WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE state oF BIODIVERSITY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Methods 17 Chapter 3 Freshwater fishes 18 Chapter 4 Amphibians 36 Chapter 5 Reptiles 55 Chapter 6 Mammals 75 Chapter 7 Avifauna 89 Chapter 8 Flora & Vegetation 112 Chapter 9 Land and Protected Areas 139 Chapter 10 Status of River Health 159 Cover page photographs by Andrew Turner (CapeNature), Roger Bills (SAIAB) & Wicus Leeuwner. ISBN 978-0-620-39289-1 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES 2 Western Cape Province State of Biodiversity 2007 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Andrew Turner [email protected] 1 “We live at a historic moment, a time in which the world’s biological diversity is being rapidly destroyed. The present geological period has more species than any other, yet the current rate of extinction of species is greater now than at any time in the past. Ecosystems and communities are being degraded and destroyed, and species are being driven to extinction. The species that persist are losing genetic variation as the number of individuals in populations shrinks, unique populations and subspecies are destroyed, and remaining populations become increasingly isolated from one another. The cause of this loss of biological diversity at all levels is the range of human activity that alters and destroys natural habitats to suit human needs.” (Primack, 2002). CapeNature launched its State of Biodiversity Programme (SoBP) to assess and monitor the state of biodiversity in the Western Cape in 1999. This programme delivered its first report in 2002 and these reports are updated every five years. The current report (2007) reports on the changes to the state of vertebrate biodiversity and land under conservation usage. -

Snake Charming and the Exploitation of Snakes in Morocco

Snake charming and the exploitation of snakes in Morocco J UAN M. PLEGUEZUELOS,MÓNICA F ERICHE,JOSÉ C. BRITO and S OUMÍA F AHD Abstract Traditional activities that potentially threaten bio- also for clothing, tools, medicine and pets, as well as in diversity represent a challenge to conservationists as they try magic and religious activities (review in Alves & Rosa, to reconcile the cultural dimensions of such activities. ). Vertebrates, particularly reptiles, have frequently Quantifying the impact of traditional activities on biodiver- been used for traditional medicine. Alves et al. () iden- sity is always helpful for decision making in conservation. In tified reptile species ( families, genera) currently the case of snake charming in Morocco, the practice was in- used in traditional folk medicine, % of which are included troduced there years ago by the religious order the on the IUCN Red List (IUCN, ) and/or the CITES Aissawas, and is now an attraction in the country’s growing Appendices (CITES, ). Among the reptile species tourism industry. As a consequence wild snake populations being used for medicine, % are snakes. may be threatened by overexploitation. The focal species for Snakes have always both fascinated and repelled people, snake charming, the Egyptian cobra Naja haje, is undergo- and the reported use of snakes in magic and religious activ- ing both range and population declines. We estimated the ities is global (Alves et al., ). The sacred role of snakes level of exploitation of snakes based on field surveys and may be related to a traditional association with health and questionnaires administered to Aissawas during – eternity in some cultures (Angeletti et al., ) and many , and compared our results with those of a study con- species are under pressure from exploitation as a result ducted years previously. -

(Equatorial Spitting Cobra) Venom a P

The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases ISSN 1678-9199 | 2011 | volume 17 | issue 4 | pages 451-459 Biochemical and toxinological characterization of Naja sumatrana ER P (Equatorial spitting cobra) venom A P Yap MKK (1), Tan NH (1), Fung SY (1) RIGINAL O (1) Department of Molecular Medicine, Center for Natural Products and Drug Research (CENAR), Faculty of Medicine, University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Abstract: The lethal and enzymatic activities of venom from Naja sumatrana (Equatorial spitting cobra) were determined and compared to venoms from three other Southeast Asian cobras (Naja sputatrix, Naja siamensis and Naja kaouthia). All four venoms exhibited the common characteristic enzymatic activities of Asiatic cobra venoms: low protease, phosphodiesterase, alkaline phosphomonoesterase and L-amino acid oxidase activities, moderately high acetylcholinesterase and hyaluronidase activities and high phospholipase A2. Fractionation of N. sumatrana venom by Resource® S cation exchange chromatography (GE Healthcare, USA) yielded nine major protein peaks, with all except the acidic protein peak being lethal to mice. Most of the protein peaks exhibit enzymatic activities, and L-amino acid oxidase, alkaline phosphomonoesterase, acetylcholinesterase, 5’-nucleotidase and hyaluronidase exist in multiple forms. Comparison of the Resource® S chromatograms of the four cobra venoms clearly indicates that the protein composition of N. sumatrana venom is distinct from venoms of the other two spitting cobras, N. sputatrix (Javan spitting cobra) and N. siamensis (Indochinese spitting cobra). The results support the revised systematics of the Asiatic cobra based on multivariate analysis of morphological characters. The three spitting cobra venoms exhibit two common features: the presence of basic, potentially pharmacologically active phospholipases A2 and a high content of polypeptide cardiotoxin, suggesting that the pathophysiological actions of the three spitting cobra venoms may be similar. -

Field Notes from Africa

Field Notes from Africa by Geoff Hammerson, November 2012 Africa! Few place names are evocative on so many levels and for such diverse reasons. Africa hosts Earth’s most spectacular megafauna, and the southern part of the continent, though temperate rather than tropical, has an extraordinarily rich and unique flora. Africa is the “cradle of humankind” and home to our closest living primate relatives. Indigenous peoples in arid southern Africa have learned to live in one of Earth’s most extreme environments. For early sea-going explorers, Africa was both an obstacle and a port of call, and later the continent proved to be a treasure-trove of diamonds, gold, and other natural resources. Sadly, Africa is also a land of human starvation, deadly disease, and genocide, and grotesque slaughter of wildlife to satisfy the superstitions and greed of people on other continents. It was a target for slave traders and a prize for imperialists. Until as recently as 1994, South Africa was a nation where basic human rights and opportunities were Our experience was greatly enhanced by the truly apportioned according to the melanin content of exceptional quality and efforts of our South African one’s skin. Africa’s exploitative and racist history guide, Patrick Cardwell, who was frequently and has made it a cauldron of political and social superbly assisted behind the scenes by Marie- turmoil. Given this mixture of alluring and Louise Cardwell. Patrick’s knowledge and repugnant characteristics, many potential visitors experience repeatedly put us in the right place at to Africa first pause and carefully consider the just the right time. -

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List

Addo Elephant National Park Reptiles Species List Common Name Scientific Name Status Snakes Cape cobra Naja nivea Puffadder Bitis arietans Albany adder Bitis albanica very rare Night adder Causes rhombeatus Bergadder Bitis atropos Horned adder Bitis cornuta Boomslang Dispholidus typus Rinkhals Hemachatus hemachatus Herald/Red-lipped snake Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Olive house snake Lamprophis inornatus Night snake Lamprophis aurora Brown house snake Lamprophis fuliginosus fuliginosus Speckled house snake Homoroselaps lacteus Wolf snake Lycophidion capense Spotted harlequin snake Philothamnus semivariegatus Speckled bush snake Bitis atropos Green water snake Philothamnus hoplogaster Natal green watersnake Philothamnus natalensis occidentalis Shovel-nosed snake Prosymna sundevalli Mole snake Pseudapsis cana Slugeater Duberria lutrix lutrix Common eggeater Dasypeltis scabra scabra Dappled sandsnake Psammophis notosticus Crossmarked sandsnake Psammophis crucifer Black-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus laevissimus Common/Red-bellied watersnake Lycodonomorphus rufulus Tortoises/terrapins Angulate tortoise Chersina angulata Leopard tortoise Geochelone pardalis Green parrot-beaked tortoise Homopus areolatus Marsh/Helmeted terrapin Pelomedusa subrufa Tent tortoise Psammobates tentorius Lizards/geckoes/skinks Rock Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus niloticus niloticus Water Monitor Lizard/Leguaan Varanus exanthematicus albigularis Tasman's Girdled Lizard Cordylus tasmani Cape Girdled Lizard Cordylus cordylus Southern Rock Agama Agama atra Burrowing -

Meerkat Survival Audience Activity Designed for 8 Years Old and Up

Meerkat Survival Audience Activity designed for 8 years old and up. You need at least two people to play. Goal Students will appreciate the important role that meerkats play within their ecosystem as well as gain a better understanding of the predator/prey relationship. Objective • To learn predator/prey relationship. • To understand the important role a meerkat serves. Conservation Message Meerkats are an important part of the ecosystem and can also help shape habitats. They create burrows that act as underground tunnel systems. Once the meerkats move on, they are used as homes for small rodents and reptiles. Meerkats are also import prey species for predators in deserts and savannas of Africa. Background Information Meerkats are native to desert habitats in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. These animals live in large communities and abide by the idea that there is safety in numbers. They will often assign a community member, or sometimes multiples members, as a lookout, called the sentinel. The sentinel is looking out for predators such as jackals and eagles. Occasionally meerkats will have a run in with venomous snakes such as the Cape Cobra. When the sentinel sees a potential danger, they will let out a sharp very high-pitched call to warn others to take cover and hide. While there are a few guarding the community, other meerkats will forage for foods and are good hunters that work together to catch rodents, insects and small reptiles. Materials Needed • 10 cups • Small light-weight ball such as ping pong ball • Pen/pencil/marker • Counters (buttons, pennies, beans, etc.) • Sticky Notes or Small Pieces of Paper with tape on back • Scenario Cards Length of Activity 40 minutes Procedure • Read the background information and gather the necessary materials. -

Cobra Risk Assessment

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Cobra (all species) Steve Csurhes and Paul Fisher First published 2010 Updated 2016 Pest animal risk assessment © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Photo: Image from Wikimedia Commons (this image is reproduced under the terms of a GNU Free Documentation License) Invasive animal risk assessment: Cobra 2 Contents Summary 4 Introduction 5 Identity and taxonomy 5 Taxonomy 3 Description 5 Diet 5 Reproduction 6 Predators and diseases 6 Origin and distribution 7 Status in Australia and Queensland 8 Preferred habitat 9 History as a pest elsewhere 9 Uses 9 Pest potential in Queensland 10 Climate match 10 Habitat suitability 10 Broad natural geographic range 11 Generalist diet 11 Venom production 11 Disease 11 Numerical risk analysis 11 References 12 Attachment 1 13 Invasive animal risk assessment: Cobra 3 Summary The common name ‘cobra’ applies to 30 species in 7 genera within the family Elapidae, all of which can produce a hood when threatened. All cobra species are venomous. As a group, cobras have an extensive distribution over large parts of Africa, Asia, Malaysia and Indonesia. -

An in Vivo Examination of the Differences Between Rapid

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN An in vivo examination of the diferences between rapid cardiovascular collapse and prolonged hypotension induced by snake venom Rahini Kakumanu1, Barbara K. Kemp-Harper1, Anjana Silva 1,2, Sanjaya Kuruppu3, Geofrey K. Isbister 1,4 & Wayne C. Hodgson1* We investigated the cardiovascular efects of venoms from seven medically important species of snakes: Australian Eastern Brown snake (Pseudonaja textilis), Sri Lankan Russell’s viper (Daboia russelii), Javanese Russell’s viper (D. siamensis), Gaboon viper (Bitis gabonica), Uracoan rattlesnake (Crotalus vegrandis), Carpet viper (Echis ocellatus) and Puf adder (Bitis arietans), and identifed two distinct patterns of efects: i.e. rapid cardiovascular collapse and prolonged hypotension. P. textilis (5 µg/kg, i.v.) and E. ocellatus (50 µg/kg, i.v.) venoms induced rapid (i.e. within 2 min) cardiovascular collapse in anaesthetised rats. P. textilis (20 mg/kg, i.m.) caused collapse within 10 min. D. russelii (100 µg/kg, i.v.) and D. siamensis (100 µg/kg, i.v.) venoms caused ‘prolonged hypotension’, characterised by a persistent decrease in blood pressure with recovery. D. russelii venom (50 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg, i.m.) also caused prolonged hypotension. A priming dose of P. textilis venom (2 µg/kg, i.v.) prevented collapse by E. ocellatus venom (50 µg/kg, i.v.), but had no signifcant efect on subsequent addition of D. russelii venom (1 mg/kg, i.v). Two priming doses (1 µg/kg, i.v.) of E. ocellatus venom prevented collapse by E. ocellatus venom (50 µg/kg, i.v.). B. gabonica, C. vegrandis and B. -

Annual Report 2017

3 CONTACT DETAILS Dean Prof Danie Vermeulen +27 51 401 2322 [email protected] MARKETING MANAGER ISSUED BY Ms Elfrieda Lötter Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences +27 51 401 2531 University of the Free State [email protected] EDITORIAL COMPILATION PHYSICAL ADDRESS Ms Elfrieda Lötter Room 9A, Biology Building, Main Campus, Bloemfontein LANGUAGE REVISION Dr Cindé Greyling and Elize Gouws POSTAL ADDRESS University of the Free State REVISION OF BIBLIOGRAPHICAL DATA PO Box 339 Dr Cindé Greyling Bloemfontein DESIGN, LAYOUT South Africa )LUHÀ\3XEOLFDWLRQV 3W\ /WG 9300 PRINTING Email: [email protected] SA Printgroup )DFXOW\ZHEVLWHZZZXIVDF]DQDWDJUL 4 NATURAL AND AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES REPORT 2017 CONTENT PREFACE Message from the Dean 7 AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES Agricultural Economics 12 Animal, Wildlife and Grassland Sciences 18 Plant Sciences 26 Soil, Crop and Climate Sciences 42 BUILDING SCIENCES Architecture 50 Quantity Surveying and Construction Management 56 8UEDQDQG5HJLRQDO3ODQQLQJ NATURAL SCIENCES Chemistry 66 Computer Sciences and Informatics 80 Consumer Sciences 88 Genetics 92 Geography 100 Geology 106 Mathematical Statistics and Actuarial Science 112 Mathematics and Applied Mathematics 116 Mathematics 120 0LFURELDO%LRFKHPLFDODQG)RRG%LRWHFKQRORJ\ Physics 136 Zoology and Entomology 154 5 Academic Centres Disaster Management Training and Education Centre of Africa - DiMTEC 164 Centre for Environmental Management - CEM 170 Centre for Microscopy 180 6XVWDLQDEOH$JULFXOWXUH5XUDO'HYHORSPHQWDQG([WHQVLRQ Paradys Experimental Farm 188 Engineering Sciences 192 Institute for Groundwater Studies 194 ACADEMIC SUPPORT UNITS Electronics Division 202 Instrumentation 206 STATISTICAL DATA Statistics 208 LIST OF ACRONYMS List of Acronyms 209 6 NATURAL AND AGRICULTURAL SCIENCES REPORT 2017 0(66$*( from the '($1 ANNUAL REPORT 2016 will be remembered as one of the worst ±ZKHUHHDFKELQFRXOGFRQWDLQDXQLTXHSURGXFWDQG years for tertiary education in South Africa due once a product is there, it remains. -

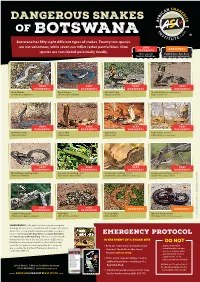

Botswana Has Fifty Eight Different Types of Snakes

DANGEROUS SNAKES OF B OT SWA NA Botswana has fifty eight different types of snakes. Twenty two species are not venomous, while seven can inflict rather painful bites. Nine VERY DANGEROUS species are considered potentially deadly. DANGEROUS Has caused Painful bite, but does human fatalities not require antivenom VERY VERY VERY VERY DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS Black Mamba Black Mamba Snouted Cobra Snouted Cobra - banded phase (Dendroaspis polylepis) (Dendroaspis polylepis) (Naja annulifera) (Naja annulifera) VERY VERY VERY VERY DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS Anchieta’s Cobra Cape Cobra Cape Cobra Cape Cobra - juvenile (Naja anchietae) (Naja nivea) (Naja nivea) (Naja nivea) Photo Marius Burger VERY VERY VERY VERY DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS Mozambique Spitting Cobra Common Boomslang - male Common Boomslang - female Common Boomslang - juvenile (Naja mossambica) (Dispholidus typus viridis) (Dispholidus typus viridis) Photo André Coetzer (Dispholidus typus viridis) VERY VERY DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS DANGEROUS Southern Twig Snake Puff Adder Horned Adder Bibron’s Stiletto Snake (Thelotornis capensis capensis) (Bitis arietans arietans) (Bitis caudalis) (Atractaspis bibronii) Photo Warren Dick © Johan Marais African Snakebite Institute Snakebite African © Johan Marais JOHAN MARAIS is the author of various books on reptiles including the best-seller A Complete Guide to Snakes of Southern Africa. He is a popular public speaker and offers a variety of courses including Snake Awareness, Scorpion Awareness EMERGENCY PROTOCOL and Venomous Snake Handling. Johan is accredited by the International Society of Zoological Sciences (ISZS) and is a IN THE EVENT OF A SNAKE BITE Field Guides Association of Southern Africa (FGASA) and DO NOT ww Travel Doctor-approved service provider. His courses are 1 Keep the victim calm, immobilized and .. -

Quantitative Characterization of the Hemorrhagic, Necrotic, Coagulation

Hindawi Journal of Toxicology Volume 2018, Article ID 6940798, 8 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/6940798 Research Article Quantitative Characterization of the Hemorrhagic, Necrotic, Coagulation-Altering Properties and Edema-Forming Effects of Zebra Snake (Naja nigricincta nigricincta)Venom Erick Kandiwa,1 Borden Mushonga,1 Alaster Samkange ,1 and Ezequiel Fabiano2 1 School of Veterinary Medicine, Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Neudamm Campus, University of Namibia, P. Bag 13301, Pioneers Park, Windhoek, Namibia 2Department of Wildlife Management and Ecotourism, Katima Mulilo Campus, Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of Namibia, P. Bag 1096, Ngweze, Katima Mulilo, Namibia Correspondence should be addressed to Alaster Samkange; [email protected] Received 30 May 2018; Revised 5 October 2018; Accepted 10 October 2018; Published 24 October 2018 Academic Editor: Anthony DeCaprio Copyright © 2018 Erick Kandiwa et al. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Tis study was designed to investigate the cytotoxicity and haemotoxicity of the Western barred (zebra) spitting cobra (Naja nigricincta nigricincta) venom to help explain atypical and inconsistent reports on syndromes by Namibian physicians treating victims of human ophidian accidents. Freeze-dried venom milked from adult zebra snakes was dissolved in phosphate bufered saline (PBS) for use in this study. Haemorrhagic and necrotic activity of venom were studied in New Zealand albino rabbits. Oedema-forming activity was investigated in 10-day-old Cobb500 broiler chicks. Procoagulant and thrombolytic activity was investigated in adult Kalahari red goat blood in vitro. -

Snakes of Durban

SNakes of durban Brown House Snake Herald Snake Non - venomous Boaedon capensis Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Often found near human habitation where they Also referred to as the Red-lipped herald. hunt rodents, lizards and small birds. This nocturnal (active at night) snake feeds They are active at night and often collected mainlyly on frogs and is one of the more common for the pet trade. snakes found around human dwellings. SPOTTED BUSH Snake Eastern Natal Green Snake Southern Brown Egg eater Philothamnus semivariegatus Philothamnus natalensis natalensis Dasypeltis inornata Probably the most commonly found snake in This green snake is often confused with the This snake has heavily keeled body scales and urban areas. They are very good climbers, Green mamba. This diurnal species, (active during is nocturnal (active at night) . Although harmless, often seen hunting geckos and lizards the day) actively hunts frogs and geckos. they put up an impressive aggression display, in the rafters of homes. Max length 1.1 metres. with striking and open mouth gaping. Can reach This diurnal species (active during the day) over 1 metre in length and when they are that big is often confused with the Green mamba. they can eat chicken eggs. Habitat includes Max length 1.1 metres. grasslands, coastal forests and it frequents suburban gardens where they are known to enter aviaries in search of eggs. night adder Causus rhombeatus A common snake often found near ponds and dams because they feed exclusively on amphibians. They have a cytotoxic venom and bite symptoms will include pain and swelling. Max length 1 metre.