The Sentinelese- Indigenous Tribes. Globalism, and the Preservation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Self Determination and Indigenous People: the Fight for 'Commons'

144 Medico-legal Update, January-March 2020, Vol.20, No. 1 DOI Number: 10.37506/v20/i1/2020/mlu/194313 Self Determination and Indigenous People: The Fight For ‘Commons’ Swati Mohapatra Assistant Professor, School of Law, K.I.I.T , Deemed to be University Abstract History has always seen the less-privileged as the one suffering the alienation of their rights, entitlements. It is equally true that these communities have fought back to claim what is rightfully theirs. The principle of Self determination or the right to decide how to be governed can be traced back to World War-1 and the principles laid down by Woodrow Wilson. This right to Self determination exists for each one of us. This becomes even more imminent when it belongs to a community which has its own preserved culture to protect, it has its own resources of which it is the foremost protector. Here the paper emphasizes how the tribals in India have now been reduced to a mere dependant and beggary.The paper traces the various changes of the Indian legal system governing the relationship between the ‘Commons’ and the Tribal Communities. But ‘the history of Forests is the history of conflicts’. The researcher has taken two case studies- the struggles of the Dongria-Kondhs of Odisha and the Sentinelese from Andaman , to show how these communities have in their own unparalleled ways protect their Commons from the never-ending appetite of the industrialization and human greed. Lastly, the researcher has analysed various provisions from the Corpus of Indian laws, to find out where is the State missing out. -

The Last Island of the Savages

The Last Island of the Savages Journeying to the Andaman Islands to meet the most isolated tribe on Earth By Adam Goodheart | September 5, 2000 Ana Raquel S. Hernandes/Flickr The lumps of white coral shone round the dark mound like a chaplet of bleached skulls, and everything around was so quiet that when I stood still all sound and all movement in the world seemed to come to an end. It was a great peace, as if the earth had been one grave, and for a time I stood there thinking mostly of the living who, buried in remote places out of the knowledge of mankind, still are fated to share in its tragic or grotesque miseries. In its noble struggles too—who knows? The human heart is vast enough to contain all the world. It is valiant enough to bear the burden, but where is the courage that would cast it off? —Joseph Conrad, Lord Jim Shortly before midnight on August 2, 1981, a Panamanian-registered freighter called the Primrose, which was traveling in heavy seas between Bangladesh and Australia with a cargo of poultry feed, ran aground on a coral reef in the Bay of Bengal. As dawn broke the next morning, the captain was probably relieved to see dry land just a few hundred yards from the Primrose’s resting place: a low-lying island, several miles across, with a narrow beach of clean white sand giving way to dense jungle. If he consulted his charts, he realized that this was North Sentinel Island, a western outlier in the Andaman archipelago, which belongs to India and stretches in a ragged line between Burma and Sumatra. -

Unique Origin of Andaman Islanders: Insight from Autosomal Loci

J Hum Genet (2006) 51:800–804 DOI 10.1007/s10038-006-0026-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Unique origin of Andaman Islanders: insight from autosomal loci K. Thangaraj Æ G. Chaubey Æ A. G. Reddy Æ V. K. Singh Æ L. Singh Received: 9 April 2006 / Accepted: 1 June 2006 / Published online: 19 August 2006 Ó The Japan Society of Human Genetics and Springer-Verlag 2006 Abstract Our mtDNA and Y chromosome studies Introduction lead to the conclusion that the Andamanese ‘‘Negrito’’ mtDNA lineages have survived in the Andaman Is- The ‘‘Negrito’’ populations found scattered in parts of lands in complete genetic isolation from other South southern India, the Andaman Islands, Malaysia and the and Southeast Asian populations since the initial set- Philippines are considered to be the relic of early tlement of the region by the out-of-Africa migration. In modern humans and hence assume considerable order to obtain a robust reconstruction of the evolu- anthropological and genetic importance. Their gene tionary history of the Andamanese, we carried out a pool is slowly disappearing either due to assimilation study on the three aboriginal populations, namely, the with adjoining populations, as in the case of the Se- Great Andamanese, Onge and Nicobarese, using mang of Malaysia and Aeta of the Philippines, or due autosomal microsatellite markers. The range of alleles to their population collapse, as is evident in the case of (7–31.2) observed in the studied population and het- the aboriginals of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman erozygosity values (0.392–0.857) indicate that the se- and Nicobar Islands are inhabited by six enigmatic lected STR markers are highly polymorphic in all the indigenous tribal populations, of which four have been three populations, and genetic variability within the characterized traditionally as ‘‘Negritos’’ (the Jarawa, populations is significantly high, with a mean gene Onge, Sentinelese and Great Andamanese) and two as diversity of 77%. -

A War-Prone Tribe Migrated out of Africa to Populate the World

A war-prone tribe migrated out of Africa to populate the world. Eduardo Moreno1. 1 CNIO, Melchor Fernández Almagro, 3. Madrid 28029, Spain. Of the tribal hunter gatherers still in existence today, some lead lives of great violence, whereas other groups live in societies with no warfare and very little murder1,2,3,4,5. Here I find that hunter gatherers that belong to mitochondrial haplotypes L0, L1 and L2 do not have a culture of ritualized fights. In contrast to this, almost all L3 derived hunter gatherers have a more belligerent culture that includes ritualized fights such as wrestling, stick fights or headhunting expeditions. This appears to be independent of their environment, because ritualized fights occur in all climates, from the tropics to the arctic. There is also a correlation between mitochondrial haplotypes and warfare propensity or the use of murder and suicide to resolve conflicts. This, in the light of the “recent out of Africa” hypothesis”6,7, suggests that the tribe that left Africa 80.000 years ago performed ritualized fights. In contrast to the more pacific tradition of non-L3 foragers, it may also have had a tendency towards combat. The data implicate that the entire human population outside Africa is descended from only two closely related sub-branches of L3 that practiced ritual fighting and probably had a higher propensity towards warfare and the use of murder for conflict resolution. This may have crucially influenced the subsequent history of the world. There is little evidence for the practice of war before the late Paleolithic3,4. -

The Invisible Tribal Tourism in Andaman & Nicobar Islands

Perspectives on Business Management & Economics Volume II • September 2020 ISBN: 978-81-947738-1-8 THE INVISIBLE TRIBAL TOURISM IN ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS MOUSIME XALXO Assistant Professor, Indian Academy Degree College, Bengaluru ORCID ID: 0000-0002-7034-7646 ABSTRACT The Andaman Islands consist of 527 islands that lie in the Andaman Sea and Bay of Bengal. A total land area of 8249 sq. kms forms this beautiful union territory. The island can sustain these tribes and carry them as one of the major attractions in tourism. Tribal tourism is one of the major sources of income and attraction for tourists. Tourism and agriculture are the primary sources of income on the island. The original population of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands consists of aboriginal indigenous people that are tribal. They dwell in the forest and remain isolated for thousands of years. Tribal tourism connects to tribal culture, values, traditions, tourism products owned and operated by the tribal people. But the tribal population of the islands is not aware of the opportunity and challenges faced by them. Tribes lack in all the facilities provided by the Government because they don’t like to surround or interact with the population and are indirectly is the source and contribution to tourism. The finding of the paper states that education is the key to tribal development. Tribal children have very low levels of participation in social-cultural activities. Though the development of the tribes is taking place in India, the pace of development has been rather slow. If govt. will not take some drastic steps for the development of tribal education KEYWORDS: Tribal tourism, sustainable tourism, challenges and opportunities JEL CLASSIFICATION: D00, E00, E71 CITE THIS ARTICLE: Xalxo, Mousime. -

Protecting the Sentinelese

Protecting the Sentinelese drishtiias.com/printpdf/protecting-the-sentinelese Why in News Recently, the Anthropological Survey of India (ANSI) policy document warned of threat to the Sentinelese from commercial activity. The policy document comes almost two years after American national John Allen Chau was allegedly killed by the Sentinelese on the North Sentinel Island. Key Points 1/3 ANSI Guidelines: Any exploitation of the North Sentinel Island of the Andamans for commercial and strategic gain would be dangerous for its occupants, the Sentinelese. The Right of the people to the island is non-negotiable, unassailable and uninfringeable. The prime duty of the state is to protect these rights as eternal and sacrosanct. Their island should not be eyed for any commercial or strategic gain. The document also calls for building a knowledge bank on the Sentinelese. Since ‘on-the-spot study’ is not possible for the tribal community, anthropologists suggest the ‘study of a culture from distance’. About the Sentinelese: The Sentinelese are a pre-neolithic, negrito tribe who live in North Sentinel Island of the Andamans. They are completely isolated with no contact to the outside world. The first time they were contacted by a team of Indian anthropologists in 1991. Due to no contact, the census of Sentinelese is taken through photographing the island individuals from distance. It has a population of about 50 to 100 on the North Sentinel Island. Surveys of North Sentinel Island have not found any evidence of agriculture. Instead, the community seems to be hunter-gatherers, getting food through fishing, hunting, and collecting wild plants living on the island. -

Leptospiral Infection Among Primitive Tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands

Epidemiol. Infect. (1999), 122, 423–428. Printed in the United Kingdom # 1999 Cambridge University Press Leptospiral infection among primitive tribes of Andaman and Nicobar Islands " " " " S. C. SEHGAL *, P.VIJAYACHARI , M.V.MURHEKAR , A.P.SUGUNAN , " # S.SHARMA S. S. SINGH " Regional Medical Research Centre (Indian Council of Medical Research), Post Bag No. 13, Port Blair 744 101, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, India # G.B. Pant Hospital, Port Blair (Accepted 15 January 1998) SUMMARY The Andaman islands were known to be endemic for leptospirosis during the early part of the century. Later, for about six decades no information about the status of the disease in these islands was available. In the late 1980s leptospirosis reappeared among the settler population and several outbreaks have been reported with high case fatality rates. Besides settlers, these islands are the home of six primitive tribes of which two are still hostile. These tribes have ample exposure to environment conducive for transmission of leptospirosis. Since no information about the level of endemicity of the disease among the tribes is available, a seroprevalence study was carried out among all the accessible tribes of the islands. A total of 1557 serum samples from four of the tribes were collected and examined for presence of antileptospiral antibodies using Microscopic Agglutination Test (MAT) employing 10 serogroups as antigens. An overall seropositivity rate of 19n1% was observed with the highest rate of 53n5% among the Shompens. The seropositivity rates in the other tribes were 16n4% among Nicobarese, 22n2% among the Onges and 14n8% among the Great Andamanese. All of the tribes except the Onges showed a similar pattern of change in the seroprevalence rates with age. -

The Jarawa of the Andamans

Te Jarawa of the Andamans Rhea John and Harsh Mander* India’s Andaman Islands are home to some of the some scholars describe appropriately as ‘adverse most ancient, and until recently the most isolated, inclusion’.1 Te experience of other Andaman tribes peoples in the world. Today barely a few hundred like the Great Andamanese and the Onge highlight of these peoples survive. Tis report is about one of poignantly and sombrely the many harmful these ancient communities of the Andaman Islands, consequences of such inclusion.2 Te continued the Jarawa, or as they describe themselves, the Ang. dogged resistance of the Sentinelese to any contact with outsiders makes them perhaps the most Until the 1970s, and even to a degree until the isolated people in the world. On the other hand, 1990s, the Jarawa people fercely and ofen violently the early adverse consequences of exposure of the defended their forest homelands, fghting of a Jarawa people to diseases and sexual exploitation diverse range of incursions and ofers of ‘friendly’ by outsiders, suggest that safeguarding many forms contact—by other tribes-people, colonial rulers, of ‘exclusion’ may paradoxically constitute the best convicts brought in from mainland India by the chance for the just and humane ‘inclusion’ of these colonisers, the Japanese occupiers, independent highly vulnerable communities. India’s administration, and mainland communities settled on the islands by the Indian government. Since However, the optimal balance between isolation the 1990s, two of the three main Ang communities and contact with the outside world of such have altered their relationship with the outsider of indigenous communities is something that no many hues, accepting their ‘friendship’ and all that government in the modern world has yet succeeded came with it, including health care support, clothes, in establishing. -

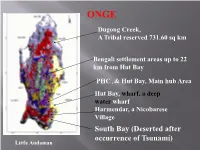

South Bay (Deserted After Occurrence of Tsunami)

ONGE Dugong Creek, A Tribal reserved 731.60 sq km Bengali settlement areas up to 22 km from Hut Bay PHC , & Hut Bay, Main hub Area Hut Bay, wharf, a deep water wharf Harmendar, a Nicobarese Village South Bay (Deserted after occurrence of Tsunami) Little Andaman Little Andaman (LA) Island once was exclusively the abode of the OG until early 1960s OG tribe, settled at Dugong Creek (DC) & South Bay, LA in 1978 Post-Tsunami situation relocated them a little away from DC The geographical isolation of Dugong and South Bay offers a secure resemblance of nomadic pursuits, and the tropical rain forest, ecology, creeks, rivulets, sea etc are conducive to sustain foraging activities throughout the year. Age-wise population Age Male Female Total Sex group) (in years) N % N % N % Ratio 0-10 25 53.19 22 46.81 47 100 880 11-20 11 57.89 08 42.11 19 100 727 21-30 07 53.85 06 46.15 13 100 857 31-40 03 30 07 70 10 100 2333 41-50 03 42.85 04 57.15 07 100 1333 51+ 04 36.36 07 63.64 11 100 1750 53 49.53 54 50.47 107 100 1019 *AAJVS *Till June 2012 Socio-Economic condition of the Onge As semi-nomad forager, hunting & fishing were their fortes, fond of dugong that they hunt on full moon night Being animists, belief on ancestral assistance in various foraging activities Observed adolescent ritual for a month long usually followed by smearing their bodies & hunting as well Body painting with red ochre & white clay common Dead is buried under the large bedstead in the hut, which is then deserted Monogamy stringently adhered to as marriage rules, re-marriage of widow or widower allowable Pre-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Onge settlement deserted Post-tsunami situation, Dugong Creek Intrinsic designs, which are usually painted by womenfolk on their loving spouses & on themselves too. -

11.31 Andaman & Nicobar Islands

11.31 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 11.31.1 Introduction Andaman & Nicobar Islands comprise 572 Islands (including islets & rocks) and has a geographical area of 8,249 sq km, constituting 0.25% of the total geographical area of the country. The Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal are to the eastern and western sides of the Islands. The Union Territory lies between 6°N to 14°N latitude and 92°E to 94°E longitudes. It comprises the Andaman and the Nicobar groups of Islands, which are separated by the 10°N channel. The islands lie along an arc in a long and narrow broken chain, approximately extending North-South over a distance more than 700 km and have a coastline of 1,962 km. The climate is humid and tropical and the humidity ranges between 70% to 90%. The average annual rainfall ranges between 1,400 mm to 3,000 mm. The weather is generally pleasant and annual temperature varies from 24°C and 28°C. The territory is drained by several small rivulets which end up as creeks often lined with dense mangroves. Kalpong is an important river in Diglipur Island. Saddle peak is the highest hill in the Islands. The only active volcano of the country, the Barren Island is located in A&N Islands. As per Census 2011, the UT is divided into 3 districts and has a total population of 0.38 million which constitute 0.03% of the country's population. The urban & rural population constitutes 62.30% and 37.70% respectively. The Tribal population is 7.61%. -

1 Linguistic Clues to Andamanese Pre-History

Linguistic clues to Andamanese pre-history: Understanding the North-South divide Juliette Blevins Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology ABSTRACT The Andaman Islands, were, until the 19th century, home to numerous hunter-gatherer societies. The ten or so tribes of Great Andamanese spread over the north and central parts of the islands are thought to have spoken related languages, while the Onge, Jangil and Jarawa of the southern parts, including Little Andaman, have been assumed to constitute a distinct linguistic family of 'Ongan' languages. Preliminary reconstruction of Proto-Ongan shows a potential link to Austronesian languages (Blevins 2007). Here, preliminary reconstructions of Proto-Great Andamanese are presented. Two interesting differences characterize the proto-languages of northern vs. southern tribes. First, sea-related terms are easily reconstructable for Proto-Great Andamanese, while the same is not true of Proto-Ongan. Second, where Proto-Ongan shows an Austronesian adstrate, Proto-Great Andamanese includes lexemes which resemble Austroasiatic reconstructions. These linguistic clues suggest distinct prehistoric origins for the two groups. 1. An introduction to languages and peoples of the Andaman Islands. The Andaman Islands are a cluster of over 200 islands in the Bay of Bengal between India and Myanmar (Burma) (see Map 1). [MAP 1 AROUND HERE; COURTESY OF GEORGE WEBER] They were once home to a range of hunter-gatherer societies, who are best known from the descriptions of Man (1883) and Radcliffe-Brown (1922). These writers, along with the Andamanese themselves, split the population of the Andamans into two primary language/culture groups, the 'Great Andaman Group' and the 'Little Andaman Group' (Radcliffe-Brown 1922:11). -

Colonial Practices in the Andaman Islands

For Cileme of course! And for Appa on his seventy fifth. 1 2 DEVELOPMENT AND ETHNOCIDE: COLONIAL PRACTICES IN THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS by Sita Venkateswar Massey University - Palmerston North Aotearoa/New Zealand IWGIA Document No. 111 - Copenhagen 2004 3 DEVELOPMENT AND ETHNOCIDE: COLONIAL PRACTICES IN THE ANDAMAN ISLANDS Author: Sita Venkateswar Copyright: IWGIA 2004 – All Rights Reserved Editing: Christian Erni and Sille Stidsen Cover design, typesetting and maps: Jorge Monrás Proofreading: Elaine Bolton Prepress and Print: Eks/Skolens Trykkeri, Copenhagen, Denmark ISBN: 87-91563-04-6 ISSN: 0105-4503 Distribution in North America: Transaction Publishers 390 Campus Drive / Somerset, New Jersey 08873 www.transactionpub.com INTERNATIONAL WORK GROUP FOR INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS Classensgade 11 E, DK 2100 - Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: (45) 35 27 05 00 - Fax: (45) 35 27 05 07 E-mail: [email protected] - Web: www.iwgia.org 4 This book has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs 5 CONTENTS Map ..............................................................................................................9 Preface ..........................................................................................................10 Prologue: a Sense of Place .......................................................................12 The island ecology ......................................................................................14 The passage to the field site ......................................................................18