Marketable Securities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imazine 2013

IIMAZINEMAZINE 20132013 VOLVOL.. 33 New Castle County Libraries’ Annual Teen Magazine Cover: Frame of Mind by Taylor B. (age 17) 2 TableTable ofof ContentsContents (cover) Frame of Mind Taylor B. 5 A Grimm Fairy Tale Chloe M. 6 Lotus in the Night Sky Sangeeta 7 Alexander and the Star Chloe M. 10 If Life Was One of Us Medha R. 12 Colossal Transformations Kayla V. 13 Spirited Jordyn V. 14 Beyond the Looking Glass Taylor B. 16 Bonnie and Frank Matthew W. 18 Complementary Color Chloe M. 19 Fall Leaves Sangeeta 20 Sleeping Beauty Taylor B. 22 Game of the Season Benjamin 24 Rise of Gold Caroline 25 Beauty of Fall Sangeeta 26 The Suspicious Friends Donovan T. 28 Time Arianna H. 29 Sundial Taylor B. 30 To the Voices Inside My Head Medha R. 31 Mistakes Matter Jordyn V. 33 Winding Path in Shadow and Light Taylor B. 34 Damsel Taylor B. 36 Give Me Arianna H. 37 Smile Medha R. 38 Vibrant Jordyn V. 39 Now this is emptiness… Taylor B. 40 Room 401 Rebekah M. 42 Wounded Soldier Caroline 45 The Hum Chloe M. 47 Day's End Jordyn V. 3 4 A Grimm Fairy Tale by Chloe M. (age 16) Like looking through a looking glass, that's not completely clear a beautiful and dark glimpse of neither here nor there a world of dim light and foreignness of deep shadows and night a place where demons kiss and angels learn to bite you see it in old stories that warn of curiosity where innocent and desperate unleash the caged ferocity those frightening tales of caution of a place that we all know that from the time we're children we fear but want to go 5 Lotus in the Night Sky by Sangeeta C. -

August 5, 2015 7:30 A.M

HEALTH COMMITTEE AGENDA Government Center, Room 400 Wednesday, August 5, 2015 7:30 a.m. 1) Roll Call 2) Chairman’s Approval of Minutes – None to approve 3) Appearance by Members of the Public 4) Departmental Matters: A. Walt Howe, Health Department Administrator 1) Items to be presented for action: a) Request for approval of an Emergency Appropriation Ordinance of the McLean County Board Amending the 2015 Combined Annual Appropriation and Budget Ordinance for Fund 0105 Health Fund for the Health Promotion Program 1-2 2) Items to be presented for information: a) Agenda and attachments from the Board of Health May 13, 2015 meeting 3-95 b) Agenda and attachments from the Board of Health July 8, 2015 meeting 96-133 c) General Report d) Other B. Bill Wasson, County Administrator 1) Items to be Presented for Information: a) Report on Recent Employment Activities 134 b) General Report c) Other 5) Other Business and Communication 6) Recommend payment of Bills and Transfers, if any, to the County Board 135-136 7) Adjournment E:\Admin (Ann)\Agenda\Health\Health.August.2015.doc An Ordinance of the McLean County Board Amending the 2015 Combined Appropriation and Budget Ordinance for Fund 0105 WHEREAS, Chapter 55, Section 5/6-1003 of the Illinois Compiled Statutes (1992) allows the County Board to approve appropriations in excess of those authorized by the budget; and, WHEREAS, the McLean County Health Department has requested an amendment to the McLean County Fiscal Year 2015 appropriation in Fund 0105 Preventive Care Fund, and the Board of Health and Finance Committee concur; and, WHEREAS, the County Board concurs that it is necessary to approve such amendment, now, therefore, BE IT ORDAINED AS FOLLOWS: 1. -

Cornell University Assembly Minutes of the November 14, 2017 Meeting 4:30 PM – 6:00 PM Room 401, Physical Sciences Building I

Cornell University Assembly Minutes of the November 14, 2017 Meeting 4:30 PM – 6:00 PM Room 401, Physical Sciences Building I. Call to Order and Roll Call a. Roll Call i. Present: J. Anderson, M. Battaglia, R. Bensel, L. Copman, M. de Roos, K. Fitch, M. Hatch, N. Jaisinghani, G. Kaufman, J. Kruser, J. Kim, E. Michel, K. Quinn, U. Smith, C. Van Loan, A. Waymack, E. Winarto ii. Absent: R. Howarth, E. Loew, A. Martinez b. Welcome and Introduction (3 minutes) c. Call for Late Additions to the Agenda (1 minute) II. President Martha Pollack and Vice President for University Relations Joel Malina (25 minutes) a. President Martha Pollack gave some updates to the University Assembly. i. She said that the Breazzano Family Center for Business Education in Collegetown was dedicated on October 18, 2017, and that the newly renovated Cornell Health was dedicated on October 20, 2017. ii. She said that are five new hires to the CAPS program. She also discussed the campus climate, speaking on the Alternative Dispute Resolution program, the Presidential Task Force, the Panhellenic Council, and the new Free Speech Presidential Speaker Series. iii. She said that she is pleased with the University Assembly’s work on the Campus Code of Conduct and the issues of Hate Speech. She said that she encourages the Codes and Judicial Committee and the Presidential Task Force to work together and engage in outreach. iv. She said that she received Resolution #4: Addressing Housekeeping Changes and Laying the Groundwork for a Holistic Evaluation of the Campus Code of Conduct last week, and that she is reviewing the resolution, and may be able to accept nearly all of the changes. -

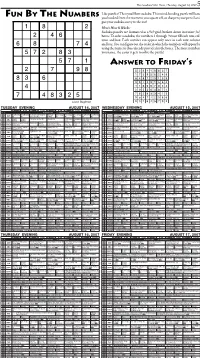

Answer to Friday's

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, August 14, 2007 5 Like puzzles? Then you’ll love sudoku. This mind-bending puzzle will have FUN BY THE NUMBERS you hooked from the moment you square off, so sharpen your pencil and put your sudoku savvy to the test! Here’s How It Works: Sudoku puzzles are formatted as a 9x9 grid, broken down into nine 3x3 boxes. To solve a sudoku, the numbers 1 through 9 must fill each row, col- umn and box. Each number can appear only once in each row, column and box. You can figure out the order in which the numbers will appear by using the numeric clues already provided in the boxes. The more numbers you name, the easier it gets to solve the puzzle! ANSWER TO FRIDAY’S TUESDAY EVENING AUGUST 14, 2007 WEDNESDAY EVENING AUGUST 15, 2007 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 6PM 6:30 7PM 7:30 8PM 8:30 9PM 9:30 10PM 10:30 E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone E S E = Eagle Cable S = S&T Telephone Dog Bounty Dog Bounty Dog the Bounty Hunter: A Mindfreak Criss Angel Criss Angel Criss Angel Dog Bounty Dog Bounty CSI: Miami: Killer Date CSI: Miami: Recoil The Sopranos: Calling All Family Family CSI: Miami: Killer Date 36 47 A&E (R) (R) Man Called Dog (TVPG) (R) (R) (R) (R) (R) 36 47 A&E (TV14) (HD) (TV14) (HD) Cars (TVMA) (HD) Jewels (R) Jewels (R) (TV14) (HD) Laughs Laughs Primetime: Crime (N) i-Caught (N) KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live According Knights NASCAR in Primetime: The Nine: The Inside Man KAKE News (:35) Nightline (:05) Jimmy Kimmel Live 4 6 ABC (TVPG) (TVPG) at 10 (N) (TV14) (R) 4 6 ABC (R) (HD) Prosp. -

Covered by Med-QUEST but Not by Kaiser Permanente” at the End of This Section

QUEST Integration Member Handbook Your introduction to Kaiser Permanente Kaiser Permanente QUEST Integration 1 Kaiser Permanente complies with applicable Federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate, exclude people, or treat people differently because of: Race Color National Origin Age Disability Sex Kaiser Permanente provides free aids and services to people with disabilities to communicate effectively with us, such as: Qualified sign language interpreters Written information in other formats (large print, audio, accessible electronic formats, other formats) Kaiser Permanente provides free language services to people whose primary language is not English, such as: Qualified interpreters Information written in other languages If you need these services, contact 808-432-5330, toll-free 1-800- 651-2237 or by TTY 711 If you believe that Kaiser Permanente has failed to provide these services or discriminated in another way, you can file a grievance with: Kaiser Civil Rights Coordinator 711 Kapiolani Blvd., Honolulu, HI 96813 Phone: 808-432-5330 or toll-free 1-800-651-2237 TTY: 711 Fax: 808-432-5300 Email: [email protected] KP19-041 Member Handbook For help or for more information please visit kpquest.org or call 808-432-5330 (Oahu), 1-800-651-2237 (toll-free), 711 (TTY) 2 Kaiser Permanente QUEST Integration You can file a grievance in person or by mail or fax. If you need help filing a grievance, the Kaiser Civil Rights Coordinator is available to help you. You can also file a grievance with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office for Civil Rights, electronically through the Office for Civil Rights Complaint Portal, available at https://ocrportal.hhs.gov/ocr/portal/lobby.jsf, or by mail or phone at: U.S. -

Community Living Guide Has Been Provided So That You Are Cognizant of the Policies and Procedures Governing the Residence Halls

0 Virginia State University 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter from the Director………………………..….……………………….3 Letter from Interim Associate Vice President....…………………….…….4 Mission & Vision……………………………………………………….5 Commitment to Diversity & Inclusion………………………………..5 Title IX……………………………………………………………...6 FERPA……………………………………………………………9 Overview of Residence Life & Housing………………………..11 Staffing……………………………………………………….11 Where to Find Help………………………………………..12 Resident’s Bill of Rights………………………………….14 Yellow Pages: STEP-BY-STEP GUIDE ResLife Policies & Procedures A-Z……………………….15 Residence Hall Safety……………………………….29 COVID-19………………………………………30 Visitation……………………………………….31 Hall Damages & Charges…………………….32 Violations…………………………………..33 Bed Bug Policy…………………………...35 Orange Pages: QUICK FACTS Items to Bring…………………………..38 Hall Closure Schedule…………………39 Social Media……………………….40 Blue Pages: READY REFERENCE Essential Areas Directory…….48 ResLife Directory…………..49 FAQs……………………50 Appendix: Move In Schedule…56 Index…………57 2 LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR Dear Students: Welcome to your home high above the Appomattox River at Virginia State University for the 2020-2021 academic year. Residence Life & Housing is extremely happy that you’ve chosen to live in our residence halls. Living in a residence hall is an exciting and an educational experience in community living. You will find many opportunities to interact socially, educationally, and culturally in our halls. The Department of Residence Life & Housing encourages you to become involved in the opportunities offered to you. Take advantage of the programs and activities planned by the residence hall staff. We hope you will participate in all aspects of the residence hall, the campus, and the community and make it a fundamental part of your education. Living in a residential community requires that you be aware of and sensitive to the needs of your fellow residents. -

Attorneys for Epstein Guards Wary of Their Clients Being Singled out For

VOLUME 262—NO. 103 $4.00 WWW. NYLJ.COM TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 2019 Serving the Bench and Bar Since 1888 ©2019 ALM MEDIA PROPERTIES, LLC. COURT OF APPEALS IN BRIEF Chinese Professor’s hearing date of Dec. 3. She also NY Highest Court Judges Spar IP Fraud Case Reassigned mentioned that the payments were coming from a defendant A third judge in the Eastern in the case discussed in the Over How to Define the Word District of New York is now sealed relatedness motion. handling the case of a Chinese While the Curcio question ‘Act’ in Disability Benefits Case citizen accused of stealing an now moves to Chen’s court- American company’s intellec- room, Donnelly issued her tual property on behalf of the order Monday on the related- Office by Patricia Walsh, who was Chinese telecom giant Huawei, ness motion. BY DAN M. CLARK injured when an inmate acciden- according to orders filed Mon- “I have reviewed the Govern- tally fell on her while exiting a day. ment’s letter motion and con- JUDGES on the New York Court of transport van. Walsh broke the CRAIG RUTTLE/AP U.S. District Judge Pamela clude that the cases are not Appeals sparred Monday over how inmate’s fall and ended up with Chen of the Eastern District of presumptively related,” she the word “act,” as in action, should damage to her rotator cuff, cervi- Tova Noel, center, a federal jail guard responsible for monitoring Jeffrey Epstein New York was assigned the case wrote. “Indeed, the Government be defined in relation to an injured cal spine, and back. -

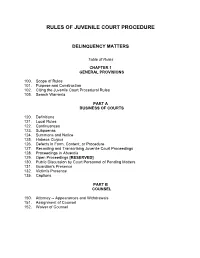

Rules of Juvenile Court Procedure

RULES OF JUVENILE COURT PROCEDURE DELINQUENCY MATTERS Table of Rules CHAPTER 1 GENERAL PROVISIONS 100. Scope of Rules 101. Purpose and Construction 102. Citing the Juvenile Court Procedural Rules 105. Search Warrants PART A BUSINESS OF COURTS 120. Definitions 121. Local Rules 122. Continuances 123. Subpoenas 124. Summons and Notice 125. Habeas Corpus 126. Defects in Form, Content, or Procedure 127. Recording and Transcribing Juvenile Court Proceedings 128. Proceedings in Absentia 129. Open Proceedings [RESERVED] 130. Public Discussion by Court Personnel of Pending Matters 131. Guardian's Presence 132. Victim's Presence 135. Captions PART B COUNSEL 150. Attorney -- Appearances and Withdrawals 151. Assignment of Counsel 152. Waiver of Counsel PART C RECORDS PART C(1) ACCESS TO JUVENILE RECORDS 160. Inspection of Juvenile File/Records 163. Release of Information to School PART C(2) MAINTAINING RECORDS 165. Design of Forms 166. Maintaining Records in the Clerk of Courts 167. Filings and Service of Court Orders and Notices PART C(3) EXPUNGING OR DESTROYING RECORDS 170. Expunging or Destroying Juvenile Court Records 172. Order to Expunge or Destroy PART D MASTERS 185. Appointment to Cases 187. Authority of Master 190. Admissions Before Master 191. Master's Findings and Recommendation to the Judge 192. Challenge to Master’s Recommendation CHAPTER 2 COMMENCEMENT OF PROCEEDINGS, ARREST PROCEDURES, WRITTEN ALLEGATION AND PRE-ADJUDICATORY DETENTION PART A COMMENCING PROCEEDINGS 200. Commencing Proceedings PART B ARREST PROCEDURES IN DELINQUENCY CASES (a) Arrest Warrants 2 210. Arrest Warrants 211. Requirements for Issuance 212. Duplicate and Alias Warrants of Arrest 213. Execution of Arrest Warrant (b) Arrests Without Warrant 220. -

Rockefeller Statement to the Senate Committee” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 29, folder “Rockefeller, Nelson - Confirmation Hearings: Rockefeller Statement to the Senate Committee” of the John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald R. Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 29 of The John Marsh Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library EMBARGO EMBARGO EMBARGO THE ATTACHED IS FOR RELEASE AT 10 A.M. (E.S.T.) ON WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 1974, AND NOT PRIOR THERETO. CARE MUST BE EXERCISED TO AVOID PREMATURE RELEASE WHETHER BY DIRECT QUOTATION OR EXCERPT OF INFORMATION. ' EMBARGO EMBARGO EMBARGO ~e ·. LA t\ I \d N!A(.,~ l r c0 r r (\'1'\M i 111\ W·1-)~ $' J btt · f, no n Corp· ~ lq~l _. - November 13, 1974 10:00 A.M. Mr. Chairman, Distinguished Members of the Committee on Rules and Administration of the United States Senate: It is a privilege to have the opportunity of appearing before you again, and I look forward again to answering, freely and fully, any and all questions. -

Convention Officials Special Events Featured Speakers Sessions For

Local Welcome 3 Convention Welcome 4 Convention Officials 5 Special Events 6 Keynote Speakers 8 Featured Speakers 9 Sessions for Administrators 12 Middle School Sessions 12 Multimedia Sessions 13 Thursday at a Glance 14 Thursday Sessions 15 Friday at a Glance 24 Friday Sessions 30 Saturday at a Glance 46 Saturday Sessions 52 Hotel Map 90 Sponsor Thank You 92 1 Contents philadelphia We the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility,- pro The summer of 1776 was a hot one in Philadelphia, the site of the Second Conti- vide for the commonnental defense, Congress. promote Temperatures the general were welfare, rising in andthe smallsecure room the where blessings the delegates of liberty were to ourselves and our posterity, meeting, and the tension around the issue of the day — independence — was doing do ordain and establishnothing this Constitutionto cool things down.for the Eventually, United theStates colonies of declaredAmerica. their We independencethe people of from the United States, in order elcome to our fair city, the City of Brotherly Love, Philadelphia, America’s Most Historic Square Mile. In Britain. The moment was announced with the chime of a bell, which rang out across the city. this mile you can visit the Liberty Bell, the new National Constitution Center, Ben Franklin’s office and the place to form a more perfectWar union, resulted, establish but justice,within ainsure few years domestic the delegates tranquility, in Philadelphia provide turned for the their common defense, promote the where the Constitution was signed, just a block from the beautiful Convention Center attached to the Philadelphia attention from fighting for revolution to building the architecture of a new nation, one general welfare, andfounded secure on the liberty. -

April Chamberline 2018

Utility April 2018 Spring is in the air! Can you smell the fresh aroma of flowers and feel the refreshing raindrops of April showers? There is something about spring after surviving a cold, snowy winter and not being able to enjoy the sunshine and the great outdoors. With it, spring brings a fresh start and here at the Chamber we are in the spring season. There is a lot of cleaning up as well as creating new events and avenues of promoting the Chamber as well as Shippensburg. Many of the committees that have been an important part of the Chamber for years are being reinvigorated and Chamber of Commerce reevaluated. What would the Chamber be without all of the amazing volunteers that constantly give of their time and resources to serve on Boards and committees to assure that the Chamber and all of its committees Amanda Ridgway………..…..Ridgway Real Estate Board of Directors and Staff succeed. To them, we say a huge THANK YOU! Mitchell Burrows……………..University Grille Chair: James Zimmerman…………..New Enterprise Stone & Lime Co., Inc. The Chamber is celebrating its 80�� anniversary this year and looking back through the history of the Dan Baer……………………..….ACNB Bank Anne Detter Schaffner……..S.U. Foundation Vice Chair: Steve Oldt………………………..Shippensburg Township Shippensburg Area Chamber of Commerce, this Chamber has always been a vital component in the Vicky Simmel…………………..Gannon Associates Insurance Rich Capozzi……………………..StretchPak, Inc. Shippensburg community even in its early days with advocating for business community, connecting with the Treasurer: Scott Eckenrode……………….Aqua Power Pros/Creative Engraving Plus community in a variety of community service projects, and being key in economic and development. -

1972 Annual Review (PDF)

mfi Rockefeller Brothers Fund Annual Report 1972 RBF Rockefeller Brothers Fund Annual Report 1972 30 Rockefeller Plaza, New York, New York 10020, Telephone: 212 - CI 7-8135 Table of Contents Page Winthrop Rockefeller Memorial 4 Introduction 8 International Program 11 Grants 23 Financial Information 80 Trustees 97 Officers 98 Staff Associates 99 This printed report includes the information submitted by the Rocl<efeiier Brothers Fund to the Internal Revenue Service as required of private foundations under Section 6056 of the Internal Revenue Code. Winthrop Rockefeller: May 1,1912-February22,1973 Winthrop Rockefeller, a founder and trustee of the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, died of cancer in February after an illness of less than a year. His death removes from American philanthropy a highly individualistic force which found its chief outlet in personal service. The personal qualities manifested in Winthrop Rockefeller's public service dominated the flood of affection that appeared in print in Arkansas, where he had lived for twenty years and whose governor he had been. "A giant of a man with a spirit to match"; "a man of courage, convictions and compassion"; "a major healer of the state's racial divisions"; "a warm and compassionate man"—these attributes of the individual were constantly repeated in the tributes. Assessments of Winthrop Rockefeller as governor were invariably balanced by recollections of him as a person: his appetite for life; his exuberant pride in the role of Squire of Winrock Farms (and his fun in describing himself as a simple, hilltop Arkansas farmer); his passion fortalk; his qualities as a night-person who waxed during the small hours while others waned; his irresistible urge to listen to personal problems...