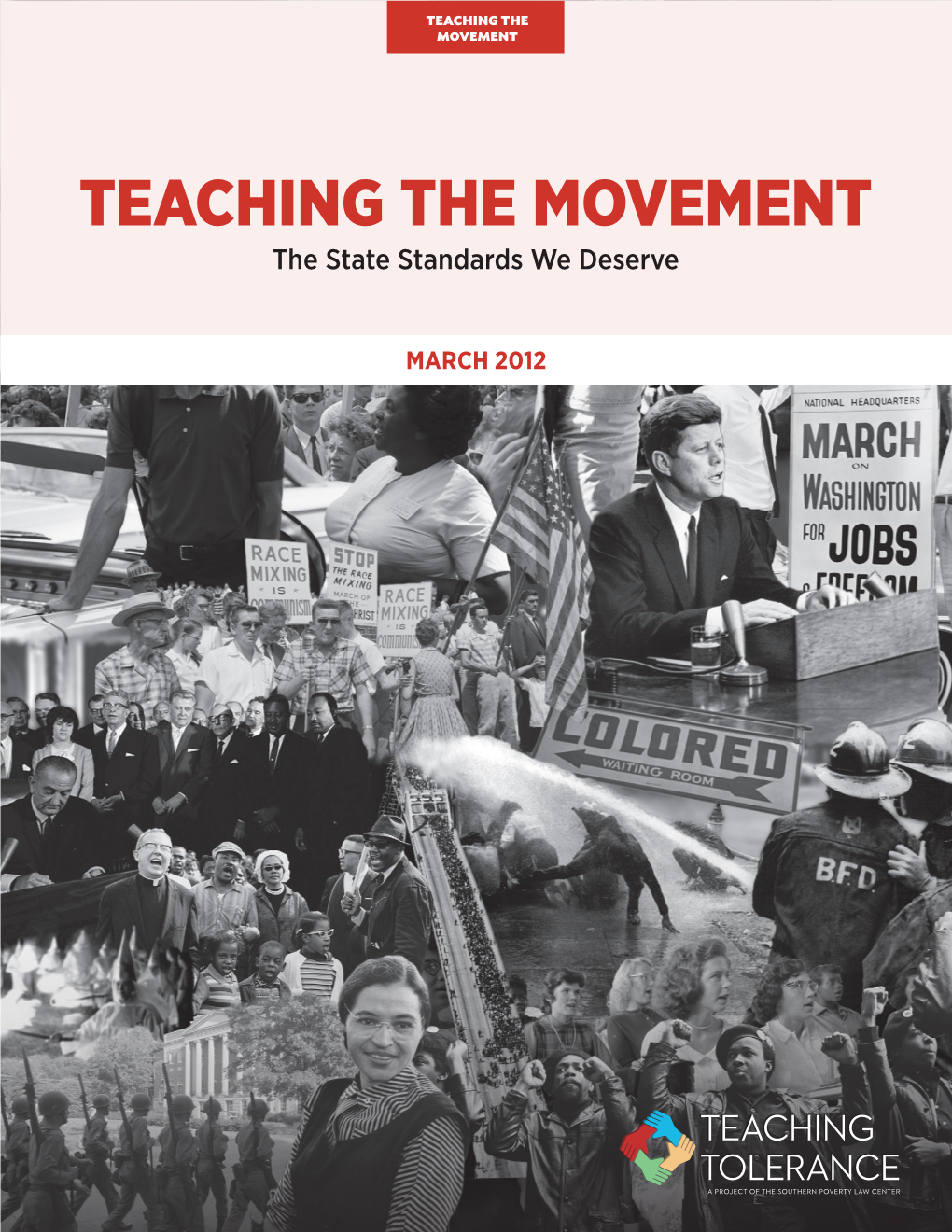

Teaching the Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Everything Is a Story

EVERYTHING IS A STORY Editor Maria Antónia Lima EVERYTHING IS A STORY: CREATIVE INTERACTIONS IN ANGLO-AMERICAN STUDIES Edição: Maria Antónia Lima Capa: Special courtesy of Fundação Eugénio de Alemida Edições Húmus, Lda., 2019 End.Postal: Apartado 7081 4764-908 Ribeirão – V. N. Famalicão Tel. 926 375 305 [email protected] Printing: Papelmunde – V. N. Famalicão Legal Deposit: 000000/00 ISBN: 978-989-000-000-0 CONTENTS 7 Introduction PART I – Short Stories in English 17 “It might be better not to talk”: Reflections on the short story as a form suited to the exploration of grief Éilís Ní Dhuibhne 27 Beyond Boundaries: The Stories of Bharati Mukherjee Teresa F. A. Alves 34 The Identity of a Dying Self in Tolstoy’s The Death of Ivan Ilych and in Barnes’s The Story of Mats Israelson Elena Bollinger 43 And They Lived Unhappily Ever After: A. S. Byatt’s Uncanny Wonder Tales Alexandra Chieira 52 (Re)imagining Contemporary Short Stories Ana Raquel Fernandes 59 “All writers are translators of the human experience”: Intimacy, tradition and change in Samrat Upadhyay’s imaginary Margarida Pereira Martins 67 Literariness and Sausages in Lydia Davis Bernardo Manzoni Palmeirim PART II – AMERICAN CREATIVE IMAGINATIONS 77 Schoolhouse Gothic: Unsafe Spaces in American Fiction Sherry R. Truffin 96 Slow time and tragedy in Gus Van Sant’s Gerry Ana Barroso 106 American Pastoralism: Between Utopia and Reality Alice Carleto 115 Kiki Smith or Kiki Frankenstein: The artist as monster maker Maria Antónia Lima 125 Edgar Allan Poe’s Gothic Revisited in André Øvredal’s -

Commonlit | Showdown in Little Rock

Name: Class: Showdown in Little Rock By USHistory.org 2016 This informational text discusses the Little Rock Nine, a group of nine exemplary black students chosen to be the first African Americans to enroll in an all-white high school in the capital of Arkansas, Little Rock. Arkansas was a deeply segregated southern state in 1954 when the Supreme Court ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional. The Little Rock Crisis in 1957 details how citizens in favor of segregation tried to prevent the integration of the Little Rock Nine into a white high school. As you read, note the varied responses of Americans to the treatment of the Little Rock Nine. [1] Three years after the Supreme Court declared race-based segregation illegal, a military showdown took place in the capital of Arkansas, Little Rock. On September 3, 1957, nine black students attempted to attend the all-white Central High School. The students were legally enrolled in the school. The National Association for the Advancement of "Robert F. Wagner with Little Rock students NYWTS" by Walter Colored People (NAACP) had attempted to Albertin is in the public domain. register students in previously all-white schools as early as 1955. The Little Rock School Board agreed to gradual integration, with the Superintendent Virgil Blossom submitting a plan in May of 1955 for black students to begin attending white schools in September of 1957. The School Board voted unanimously in favor of this plan, but when the 1957 school year began, the community still raged over integration. When the black students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” attempted to enter Central High School, segregationists threatened to hold protests and physically block the students from entering the school. -

The Limits of “Diversity” Where Affirmative Action Was About Compensatory Justice, Diversity Is Meant to Be a Shared Benefit

The Limits of “Diversity” Where affirmative action was about compensatory justice, diversity is meant to be a shared benefit. But does the rationale carry weight? By Kelefa Sanneh, THE NEW YORKER, October 9, 2017 This summer, the Times reported that, under President Trump, the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice had acquired a new focus. The division, which was founded in 1957, during the fight over school integration, would now be going after colleges for discriminating against white applicants. The article cited an internal memo soliciting staff lawyers for “investigations and possible litigation related to intentional race-based discrimination in college and university admissions.” But the memo did not explicitly mention white students, and a spokesperson for the Justice Department charged that the story was inaccurate. She said that the request for lawyers related specifically to a complaint from 2015, when a number of groups charged that Harvard was discriminating against Asian-American students. In one sense, Asian-Americans were overrepresented at Harvard: in 2013, they made up eighteen per cent of undergraduates, despite being only about five per cent of the country’s population. But at the California Institute of Technology, which does not employ racial preferences, Asian- Americans made up forty-three per cent of undergraduates—a figure that had increased by more than half over the previous two decades, while Harvard’s percentage had remained relatively flat. The plaintiffs used SAT scores and other data to argue that administrators had made it “far more difficult for Asian-Americans than for any other racial and ethnic group of students to gain admission to Harvard.” They claimed that Harvard, in its pursuit of racial parity, was not only rewarding black and Latino students but also penalizing Asian-American students—who were, after all, minorities, too. -

Untimely Meditations: Reflections on the Black Audio Film Collective

8QWLPHO\0HGLWDWLRQV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH%ODFN$XGLR )LOP&ROOHFWLYH .RGZR(VKXQ Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Number 19, Summer 2004, pp. 38-45 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\'XNH8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/nka/summary/v019/19.eshun.html Access provided by Birkbeck College-University of London (14 Mar 2015 12:24 GMT) t is no exaggeration to say that the installation of In its totality, the work of John Akomfrah, Reece Auguiste, Handsworth Songs (1985) at Documentall introduced a Edward George, Lina Gopaul, Avril Johnson, David Lawson, and new audience and a new generation to the work of the Trevor Mathison remains terra infirma. There are good reasons Black Audio Film Collective. An artworld audience internal and external to the group why this is so, and any sus• weaned on Fischli and Weiss emerged from the black tained exploration of the Collective's work should begin by iden• cube with a dramatically expanded sense of the historical, poet• tifying the reasons for that occlusion. Such an analysis in turn ic, and aesthetic project of the legendary British group. sets up the discursive parameters for a close hearing and viewing The critical acclaim that subsequently greeted Handsworth of the visionary project of the Black Audio Film Collective. Songs only underlines its reputation as the most important and We can locate the moment when the YBA narrative achieved influential art film to emerge from England in the last twenty cultural liftoff in 1996 with Douglas Gordon's Turner Prize vic• years. It is perhaps inevitable that Handsworth Songs has tended tory. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE September 25, 1997

H7838 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð HOUSE September 25, 1997 and $200 billion deficits as far as the willing to go to any length to overturn thing sometime. When is this House eye could see. the election of Congresswoman LORET- going to be ready? When will the lead- With a determination to save the TA SANCHEZ. The committee majority ership of this House be prepared to American dream for the next genera- is in the process of sharing the Immi- clean up the campaign finance mess we tion, the Republican Congress turned gration and Naturalization Service have in this country? the tax-and-spend culture of Washing- records of hundreds of thousands of Or- This House, the people's House, ton upside down and produced a bal- ange County residents with the Califor- should be the loudest voice in the cho- anced budget with tax cuts for the nia Secretary of State. These records rus. We must put a stop to big money American people. Now that the Federal contain personal information on law- special interests flooding the halls of Government's financial house is finally abiding U.S. citizens, many of them our Government. It is time, Madam in order, the big question facing Con- targeted by committee investigators Speaker, for the Republican leadership gress, and the President, by the way, is simply because they have Hispanic sur- to join with us to tell the American what is next? With the average family names or because they reside in certain people that the buck stops here. still paying more in taxes than they do neighborhoods, and that is an outrage. -

The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillm

“A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By: Thomas Anthony Gass, M.A. Department of History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Hasan Kwame Jeffries, Advisor Dr. Kevin Boyle Dr. Curtis Austin 1 Copyright by Thomas Anthony Gass 2014 2 Abstract “A Mean City”: The NAACP and the Black Freedom Struggle in Baltimore, 1935-1975” traces the history and activities of the Baltimore branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) from its revitalization during the Great Depression to the end of the Black Power Movement. The dissertation examines the NAACP’s efforts to eliminate racial discrimination and segregation in a city and state that was “neither North nor South” while carrying out the national directives of the parent body. In doing so, its ideas, tactics, strategies, and methods influenced the growth of the national civil rights movement. ii Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to the Jackson, Mitchell, and Murphy families and the countless number of African Americans and their white allies throughout Baltimore and Maryland that strove to make “The Free State” live up to its moniker. It is also dedicated to family members who have passed on but left their mark on this work and myself. They are my grandparents, Lucious and Mattie Gass, Barbara Johns Powell, William “Billy” Spencer, and Cynthia L. “Bunny” Jones. This victory is theirs as well. iii Acknowledgements This dissertation has certainly been a long time coming. -

Martin Luther King Jr., Cesar Chavez, and the Images of Their Movements

MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ, AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by ANDREA SHAN JOHNSON Dr. Robert Weems, Jr., Dissertation Supervisor MAY 2006 © Copyright by Andrea Shan Johnson 2006 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled MIXED UP IN THE MAKING: MARTIN LUTHER KING JR., CESAR CHAVEZ AND THE IMAGES OF THEIR MOVEMENTS Presented by Andrea Shan Johnson A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of History And hereby certify that in their opinion it is worthy of acceptance. __________________________________________________________ Professor Robert Weems, Jr. __________________________________________________________ Professor Catherine Rymph __________________________________________________________ Professor Jeffery Pasley __________________________________________________________ Professor Abdullahi Ibrahim ___________________________________________________________ Professor Peggy Placier ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I owe thanks to many people for helping me in the completion of this dissertation. Thanks go first to my advisor, Dr. Robert Weems, Jr. of the History Department of the University of Missouri- Columbia, for his advice and guidance. I also owe thanks to the rest of my committee, Dr. Catherine Rymph, Dr. Jeff Pasley, Dr. Abdullahi Ibrahim, and Dr. Peggy Placier. Similarly, I am grateful for my Master’s thesis committee at Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis, Dr. Annie Gilbert Coleman, Dr. Nancy Robertson, and Dr. Michael Snodgrass, who suggested that I might undertake this project. I would also like to thank the staff at several institutions where I completed research. -

Africa Latin America Asia 110101101

PL~ Africa Latin America Asia 110101101 i~ t°ica : 4 shilhnns Eurnna " fi F 9 ahillinnc Lmarica - .C' 1 ;'; Africa Latin America Asia Incorporating "African Revolution" DIRECTOR J. M . Verg6s EDITORIAL BOARD Hamza Alavi (Pakistan) Richard Gibson (U .S.A.) A. R. Muhammad Babu (Zanzibar) Nguyen Men (Vietnam) Amilcar Cabrera (Venezuela) Hassan Riad (U.A .R .) Castro do Silva (Angola) BUREAUX Britain - 4. Leigh Street, London, W. C. 1 China - A. M. Kheir, 9 Tai Chi Chang, Peking ; distribution : Guozj Shudian, P.O . Box 399, Peking (37) Cuba - Revolucibn, Plaza de la Revolucibn, Havana ; tel. : 70-5591 to 93 France - 40, rue Franqois lei, Paris 8e ; tel. : ELY 66-44 Tanganyika - P.O. Box 807, Dar es Salaam ; tel. : 22 356 U .S.A. - 244 East 46th Street, New York 17, N. Y. ; tel. : YU 6-5939 All enquiries concerning REVOLUTION, subscriptions, distribution and advertising should be addressed to REVOLUTION M6tropole, 10-11 Lausanne, Switzerland Tel . : (021) 22 00 95 For subscription rates, see page 240. PHOTO CREDITS : Congress of Racial Equality, Bob Adelman, Leroy McLucas, Associated Press, Photopress Zurich, Bob Parent, William Lovelace pp . 1 to 25 ; Leroy LcLucas p . 26 ; Agence France- Presse p . 58 ; E . Kagan p . 61 ; Photopress Zurich p . 119, 122, 126, 132, 135, 141, 144,150 ; Ghana Informa- tion Service pp . 161, 163, 166 ; L . N . Sirman Press pp . 176, 188 ; Camera Press Ltd, pp . 180, 182, 197, 198, 199 ; Photojournalist p . 191 ; UNESCO p . 195 ; J .-P . Weir p . 229 . Drawings, cartoons and maps by Sine, Strelkoff, N . Suba and Dominique and Frederick Gibson . -

OBJ (Application/Pdf)

NEWS FROM DIRECTOR OF PUBLIC RELATIONS EXECUTIVE SECRETARY FOR RELEASE: JUNE 5, 1958 LITTLE ROCK NINE AND <RS. BATES'" TO RECEIVE ANNUAL SPINGARN M'EDAT NEV/ YORK, June 5.--Nine Negro teenagers, the first of their race to enroll in Central High School of Little Rock, and Mrs. L.C. Bates, their mentor and president of the Arkansas State Conference of Branches, have been chosen as this year's recipients of the Spingarn Medal, Roy Wilkins, executive secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, announced here today. The medal, awarded annually to a Negro American for distinguished achievement, will be presented at the 49th annual NAACP convention in Cleveland, Precedents Broken In selecting Mrs. Bates and these six girls and three boys, the Spingarn Award Committee broke two precedents. For the first time, the award, regarded as the most coveted in the field, is being given to a group rather than an individual. Also for the first time minors are recipients of the award. The children and Mrs. Bates are cited for "their courageous self-restraint in the face of extreme provocation and peril," and for "their exemplary conduct in upholding the American ideals of liberty and justice." Their role in the Little Rock crisis, the citation continues, "entitles them to the gratitude of every American who believes in law and order, equality of rights, and human decency." The young people entered Central High last September in compliance with a federal district court order. They were at first denied admittance by Arkansas state troopers acting on orders of Governor Orval E. -

The Tallahassee Bus Protest

FIELD REPORTS ON DESEGREGATION IN THE SOUTH THE TALLAHASSEE BUS PROTEST by CHARLES U. SMITH Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University and LEWIS M. KILLIAN Florida State University Published by the ANTI-DEFAMATION LEAGUE OF B'NAI B'RITH with the cooperation of THE COMMITTEE ON INTERGROUP RELATIONS THE SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF SOCIAL PROBLEMS ; י/ r February, 1958 Published by the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith 515 Madison Avenue, New York 22, N. Y. Officers: HENRY EDWARD SCHULTZ, chairman; MEIER STEINBRINK, honorary chairman; BARNEY BALABAN, A. G. BALLENGER, HERBERT H. LEHMAN, LEON LOWENSTEIN, WILLIAM SACHS, BENJAMIN SAMUELS, MELVIN H. SCHLESINGER, JESSE STEINHART, honorary vice-chairmen; JOSEPH COHEN, JEFFERSON E. PEYSER, MAX J. SCHNEIDER, vice-chairmen; BENJAMIN GREENBERG, treasurer; HERBERT LEVY, secretary; BENJAMIN R. EPSTEIN, national director; BERNARD NATH, chairman, executive committee; PAUL H. SAMPLINER, vice-chairman, executive committee; PHILIP M. KLUTZNICK, president, B'nai B'rith; MAURICE BISGYER, executive vice-president, B'nai B'rith. Staff Directors: NATHAN C, BELTH, press relations; OSCAR COHEN, program; ARNOLD FORSTER, civil rights; ALEXANDER F. MILLER, community service; J. HAROLD SAKS, administration; LESTER J. WALDMAN, executive assistant. Series Editor: OSCAR COHEN, national director, program division. THE TALLAHASSEE BUS PROTEST Community Background Tallahassee is a small city (population 27,237 in 1950) in a state which con- tains some of the most rapidly growing urban areas in the southeast. It is not an important industrial center. Its chief importance lies in the fact that it is the state capital. Perhaps its next most important characteristic is that it is the seat of two of the state's institutions of higher learning: Florida State University (white) and Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (Negro). -

Civil Rights Resproj

TheAFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE in North Carolina The Civil Rights Movement North Carolina Freedom Monument Project Research Project Lesson Plan for Teachers: Procedures ■ Students will read the introduction and time line OBJECTIVE: To become familiar with of the Civil Rights Movement independently, as a significant events in the Civil Rights Movement small group or as a whole class. and their effects on North Carolina: ■ Students will complete the research project independently, as a small group or as a whole class. 1. Students will develop a basic understanding of, and ■ Discussion and extensions follow as directed by be able to define specific terms; the teacher. 2. Students will be able to make correlations between the struggle for civil rights nationally and in North Evaluation Carolina; ■ Student participation in reading and discussion of 3. Students will be able to analyze the causes and the time line. predict solutions for problems directly related to dis- ■ Student performance on the research project. criminatory practices. Social Studies Objectives: 3.04, 4.01, 4.03, 4.04, 4.05, 5.03, 6.04, 7.02, 8.01, 8.03, 9.01, 9.02, 9.03 Social Studies Skills: 1, 2, 3 Language Arts Objectives: 1.03, 1.04, 2.01, 5.01, 6.01, 6.02 Resources / Materials / Preparations ■ Time line ■ Media Center and/or Internet access for student research. ■ This research project will take two or three class periods for the introduction and discussion of the time line and to work on the definitions. The research project can be assigned over a two- or three-week period. -

President's Remarks for Tallahassee Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King

President’s Remarks for Tallahassee Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Day “The URGENCY of NOW” Thank you to Ms. Cummings for that wonderful introduction and for all that you do to lead our efforts and engagement with Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University alumni. We appreciate your leadership. I am honored to be here with you today as we celebrate the life and legacy of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., on what would have been his 90th birthday weekend. Standing on these steps has special significance, beyond symbolism. Many of the laws that govern this great state are crafted and decided upon right here. Resources/dollars that support everything from education to health care to transportation to public safety are decided upon here by the men and women elected by citizens from the panhandle to the Florida Keys. From a distance, or from the perspective of the casual observer, it might seem as though the processes associated with what happens in the Florida Legislature are intermittent, starting at a specific date - ending on another. But when viewed much closer and by the astute observer it becomes obvious that political processes in Florida and equally in our nation in general, don’t have temporal boundaries defined by specific dates and times but rather they are continuous: occurring at sunrise, sundown, throughout the night – and throughout all seasons of the year. And thus to influence what happens here, there must be an appreciation for the simple concepts of persistence and perseverance; not waiting for tomorrow, not waiting until your ducks are all lined up in a row, not waiting until you can afford to take a risk because your finances are finally in order.