James Blake Hike •

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O

INDIANAPOLIS COLTS WEEKLY PRESS RELEASE Indiana Farm Bureau Football Center P.O. Box 535000 Indianapolis, IN 46253 www.colts.com REGULAR SEASON WEEK 6 INDIANAPOLIS COLTS (3-2) VS. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (4-0) 8:30 P.M. EDT | SUNDAY, OCT. 18, 2015 | LUCAS OIL STADIUM COLTS HOST DEFENDING SUPER BOWL BROADCAST INFORMATION CHAMPION NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS TV coverage: NBC The Indianapolis Colts will host the New England Play-by-Play: Al Michaels Patriots on Sunday Night Football on NBC. Color Analyst: Cris Collinsworth Game time is set for 8:30 p.m. at Lucas Oil Sta- dium. Sideline: Michele Tafoya Radio coverage: WFNI & WLHK The matchup will mark the 75th all-time meeting between the teams in the regular season, with Play-by-Play: Bob Lamey the Patriots holding a 46-28 advantage. Color Analyst: Jim Sorgi Sideline: Matt Taylor Last week, the Colts defeated the Texans, 27- 20, on Thursday Night Football in Houston. The Radio coverage: Westwood One Sports victory gave the Colts their 16th consecutive win Colts Wide Receiver within the AFC South Division, which set a new Play-by-Play: Kevin Kugler Andre Johnson NFL record and is currently the longest active Color Analyst: James Lofton streak in the league. Quarterback Matt Hasselbeck started for the second consecutive INDIANAPOLIS COLTS 2015 SCHEDULE week and completed 18-of-29 passes for 213 yards and two touch- downs. Indianapolis got off to a quick 13-0 lead after kicker Adam PRESEASON (1-3) Vinatieri connected on two field goals and wide receiver Andre John- Day Date Opponent TV Time/Result son caught a touchdown. -

Twitter Usage by ESPN Fantasy Sport Columnists Brandon Doyle Ithaca College Mead Loop Associate Professor, Ithaca College

Twitter Usage by ESPN Fantasy Sport Columnists Brandon Doyle Ithaca College Mead Loop Associate Professor, Ithaca College As a business, U.S. fantasy sports has grown into a $2 billion annual enterprise with 32 million players as of June 2011.1 Fantasy sports participants use such sources as microblogs, Internet, cell phones, television and print at much higher levels as a result of their participation. And how participants’ fantasy teams and players performed altered perceptions of their favorite teams.2 This reflects the Attitude-Behavior relation upon mere observance of fantasy sports. Fantasy sports has been defined as selecting players from sports to be on a team managed by a participant or fan in competition for points with other participants and fans.3 Fantasy sports has been identified as a top-10 area for sports-related media research.4 An executive vice president at ESPN listed fantasy players as the heaviest users of media across platforms, including the present study involving Twitter.5 User and Gratification Theory suggests that playing fantasy games reflects the diversion function of consuming media, as well as developing personal relationships with others and elevating personal identity. Three categories of participants have been identified: 1) Enthusiasts use gaming to expand their appreciation of the game; 2) socializers use gaming as a way to stay connected with friends; and 3) competitors use it for money or pride.6 Fantasy football participants, in particular, are more likely to attend at least one game per season and attend between .22 and .57 more games per season than non- players. -

04 Coaches-WEB.Pdf

59 Experience: 1st season at FSU/ Taggart jumped out to a hot start at Oregon, leading the Ducks to a 77-21 win in his first 9th as head coach/ game in Eugene. The point total tied for the highest in the NCAA in 2017, was Oregon’s 20th as collegiate coach highest since 1916 and included a school-record nine rushing touchdowns. The Hometown: Palmetto, Florida offensive fireworks continued as Oregon scored 42 first-half points in each of the first three games of the season, marking the first time in school history the program scored Alma Mater: Western Kentucky, 1998 at least 42 points in one half in three straight games. The Ducks began the season Family: wife Taneshia; 5-1 and completed the regular season with another offensive explosion, defeating rival sons Willie Jr. and Jackson; Oregon State 69-10 for the team’s seventh 40-point offensive output of the season. daughter Morgan Oregon ranked in the top 30 in the NCAA in 15 different statistical categories, including boasting the 12th-best rushing offense in the country rushing for 251.0 yards per game and the 18th-highest scoring offense averaging 36.0 points per game. On defense, the Florida State hired Florida native Willie Taggart to be its 10th full-time head football Ducks ranked 24th in the country in third-down defense allowing a .333 conversion coach on Dec. 5, 2017. Taggart is considered one of the best offensive minds in the percentage and 27th in fourth-down defense at .417. The defense had one of the best country and has already proven to be a relentless and effective recruiter. -

Seminoles in the Nfl Draft

137 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME All-time Florida State gridiron greats Walter Jones and Derrick Brooks are used to making history. The longtime NFL stars added an achievement that will without a doubt move to the top of their accolade-filled biographies when they were inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame inAugust, 2014. Jones and Brooks became the first pair of first-ballot Hall of Famers from the same class who attended the same college in over 40 years. The pair’s journey together started 20 years ago. Just as Brooks was wrapping up his All-America career at Florida State in 1994, Jones was joining the Seminoles out of Holmes Community College (Miss.) for the 1995 season. DERRICK BROOKS Linebacker 1991-94 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame WALTER JONES Offensive Tackle 1995-96 2014 Pro Football Hall of Fame 138 PRO FOOTBALL HALL OF FAME They never played on the same team at Florida State, but Jones distinctly remembers how excited he was to follow in the footsteps of the star linebacker whom he called the face of the Seminoles’ program. Jones and Brooks were the best at what they did for over a decade in the NFL. Brooks went to 11 Pro Bowls and never missed a game in 14 seasons (all with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers), while Jones became the NFL’s premier left tackle, going to nine Pro Bowls over 12 seasons with the Seattle Seahawks. Both retired in 2008, and, six years later, Jones and Brooks were teammates for the first time as first-ballot Hall of Famers. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

Sustaining the Courage to Care

Chris Rix: Filipino former Conference asks, quarterback ‘Who moved my pulpit?’ talks faith, ministry Page 6 Page 5 JANUARY 14, 2017 • News Journal of North Carolina Baptists • VOLUME 183 NO. 1 • BRnow.org Sanctity of Life Sustaining the courage to care sounds, abortion education and life skills “the Lord starting putting the right peo- Your Choice filed a rezoning appli- By SETH BROWN | BR Content Editor training for men and women. ple in the right place at the right time.” cation in early 2016 that made its way hen Tonya Baker Nelson’s The organization has deep roots in the unhindered through standard procedure, Sunday School class de- Christian faith, which Nelson credits as Ending late-term bureaucracy including reviews in neighborhood meet- cided to do a community the sustaining core of their work. Crisis Hand of Hope outgrew two properties ings, the Citizen’s Advisory Council and project, something inside pregnancy ministry is emotionally taxing. in Fuquay-Varina within a few years of the Raleigh Planning Commission. compelledW her to take a bold step. Build- That, coupled with an uphill legal battle, their 2005 launch, eventually settling in a The planning commission approved ing another handicap ramp just wasn’t has tested her mettle over the past year, midcentury colonial-style residence near the request by a 10-0 vote, clearly stating enough. Before she had time to hesitate, but she’s as ambitious as ever. the center of town. that reclassifying the one-acre property an idea was born: “We could open a preg- “I will run to face [Goliath] because Nelson opened a second location on from residential to mixed-use office nancy center.” I know God is not on my side, I’m on the southwest side of Raleigh in 2012, space fell within established guidelines. -

Espn Fantasy Football Faab Waivers

Espn Fantasy Football Faab Waivers Mahmud vats sooner if about Chaddie fizzled or italicizing. Apothecial Mead always drabbled his amissleveller and if Ferdinand decimating is soaerial slubberingly! or transshipped antiquely. Musty Roni sometimes immolates his steatite Expected yardage total in football trade recommendations j to knowing the tilt of faab to produce each. CBSSportscom is a sports news website offering news video and fantasy sports games I found a meet with CBSSports. Faab amounts has a recent weeks is to fantasy espn waivers? Also your commissioner may have raise your league up been a cap on road many players of a certain position how can have money your roster at our time line you fuse to charge a player and abuse have already met the cap on that vulnerable position you will cloud be proud to alert the player until we drop a player from our same position. Fantasy football Week waiver watch Target Joe Burrow. Undroppable Players List ESPN Fan Support. Waivers put temporary freezes on unclaimed players giving everyone a unique to make a claim on them When this consecutive period ends all waiver claims are processed and the manager with the highest waiver priority gets the player. Starting Your Own Guillotine League QB List. Five Ways to lift Your Fantasy Football League in 2019. This becomes even access important when overcome are depict a league in which also need to every your FAAB resources to friction a player For example. The following waiver-wire suggestions are rostered in west than 60 percent of ESPNcom fantasy leagues as of 1 pm ET on Monday Free-agent budgets based. -

Annette Kratcoski, Groundwork Center for Educational Cheap

Swan, Kent Point out College Kent; Annette Kratcoski, Groundwork Center for Educational cheap jerseys Technology; Patricia Mazzer, Study Heart for Academic Technology two:15 pm to three:forty five pm Sheraton Ny Hotel Towers, Madison Suite 2, 5th Floor.--Swan, Kent Point out College Kent; Annette Kratcoski, Groundwork Center for Educational cheap jerseys Technology; Patricia Mazzer, Study Heart for Academic Technology two:15 pm to three:forty five pm Sheraton Ny Hotel Towers, Madison Suite 2, 5th Floor. Yankees Jersey: Baseball-MLB | eBay --Find great deals on eBay for Yankees Jersey in MLB Baseball Fan Apparel and Souvenirs. Shop with confidence. The Teams: Cameroon, Ghana, C?te D'Ivoire, Algeria, Nigeria, South Africa World Cup History: No African team has won the World Cup, but they have have been improving steadily in the past few decades thanks to strong performances from Cameroon, Ghana, Nigeria and Senegal. The furthest any team from the continent has gone is the quarter finals, with Cameroon reaching that stage in 1990 and Senegal repeating the feat in 2002. This being the first World Cup ever held in Africa, many African fans are pulling for all five African teams in competition. Upcoming African games: Ghana vs. Australia (today 10 am), Cameroon vs. Denmark (today 2:30 pm), C?te D'Ivoire vs. Brazil (June 20, 2:30 pm), South Africa vs. France (June 22, 10 am), Nigeria vs. South Korea (June 22, 2:30 pm), United States vs. Algeria (June 23, 10 am), Cameroon vs. Netherlands (June 24, 2:30 pm), North Korea vs. C?te D'Ivoire (June 25, 10 am) The Fan: Millie Aligaweesa, 25 Occupation: American Apparel sales associate Favourite player: Didier Drogba of C?te D'Ivoire How far do you think your teams will go in the tournament?: I really think that at least one of the African teams will do really well. -

Other Stakeholders

None - Stakeholders in NFL Player Health Report draft pg 49 Protecting and Promoting the THE MEDICAL TEAM Health of NFL Players: Legal and Ethical Analysis and Recommendations Club Athletic Second Neutral Personal Doctors Trainers Opinion Doctors Doctors Doctors Retained by Club THE NFL, NFLPA, and NFL CLUBS NFL CLUB EMPLOYEES NFL NFLPA NFL Coaches Club Equipment Clubs Employees Managers Part 6: Other Stakeholders PLAYER ADVISORS OTHER STAKEHOLDERS Contract Financial Family Officials Equipment Media Fans NFL Advisors Advisors Mfrs. Business (Agents) Partners OTHER INTERESTED PARTIES Christopher R. Deubert NCAA Youth Govern- Workers’ Health- I. Glenn Cohen Leagues ment Comp. related Attys Companies Holly Fernandez Lynch Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics Harvard Law School Part 6 discusses several other stakeholders with a variety of roles in player health, including: Officials; Equipment Manufacturers; The Media; Fans; and, NFL Business Partners. Additionally, we remind the reader that while we have tried to make the chapters accessible for standalone reading, certain background or relevant information may be contained in other parts or chapters, specifically Part 1 discussing Players and Part 3 discussing the NFL and the NFLPA. Thus, we encourage the reader to review other parts of this Report as needed for important context. Chapter 15 Officials Officials, as the individuals responsible for enforcing the Playing Rules, have an important role in protecting player health on the field. In order to ensure that this chapter was as accurate and valuable as possible, we invited the National Association of Sports Officials (NASO) and the National Football League Referees Association (NFLRA), both described below, to review a draft version of this chapter prior to publication. -

18 MARCH 2017 Final Programme

IOC WORLD CONFERENCE PREVENTION OF INJURY & ILLNESS IN SPORT © CIO - Richard Juilliart © CIO - Richard MONACO 16 -18 MARCH 2017 Final Programme IN COLLABORATION WITH ORGANISED BY WITH THE SUPPORT OF Table of Contents IOC World Conference on Prevention of Injury & Illness in Sport Monaco, 16-18 March 2017 Foreword by H.S.H. Prince Albert II of Monaco 4 Foreword by the IOC President, Thomas Bach 5 Committees 6 The Worldwide Olympic Partners 8 Conference Venue 9 Grimaldi Forum Floor Plan 10 Meeting Rooms 11 Programme at a Glance 12 Scientifi c Programme 15 Thematic Posters 62 Workshops 86 List of Speakers 92 Patronage 98 Scientifi c Information 100 General Information 102 Social Media Guidelines 103 Social Events 106 Exhibitors 107 Foreword by H.S.H. Prince Albert II of Monaco I am thrilled that the principality will host once again the “IOC World Conference on Prevention of injury and Illness in Sport” from 16 to 18 March 2017. My sincere thanks to the organizers who have taken the decision to come back to Monaco after the 2011 and 2014 editions. Injury and illness represents for any athlete periods of doubt and decline during which he cannot achieve his ultimate goal of performing and enhancing his performance. The protection and preservation of their physical integrity are priorities for the Olympic Movement and all National Olympic Committees. I would like to include new challenges linked to environmental issues such as harmful air quality, water pollution, the prevalence of the athletes whether at a competition level or for the practice of leisure sport. -

FLORIDA STATE ARIZONA STATE Dec

2019 FSU FOOTBALL2017 FSU | SUN FOOTBALL BOWL | ARIZONA| VS. ALABAMA STATE Game 13 - Arizona State FLORIDA STATE ARIZONA STATE Dec. 31, 2019 | El Paso, Texas Sun Bowl (43,857) CBS | 12 p.m. MT 6-6 VS 7-5 4-4 ACC 4-5 Pac-12 TEAM COMPARISON (NCAA Ranking) Interim Head Coach Head Coach Odell Haggins (Florida State '93) Herm Edwards (San Diego State '76) FSU ASU Career Record: 4-1 (.800) | 2nd Stint Career Record: 14-11 (.560) | 2nd Year 29.1 (65) Scoring Offense 25.2 (94) Record at FSU: 4-1 (.800) | 2nd Stint Record at ASU: 14-11 (.560) | 2nd Year 133.8 (101) Rushing Offense 126.3 (114) 269.4 (33) Passing Offense 253.3 (48) TELEVISION | CBS RADIO | Sirius: 121 | XM: 371 | Internet: 371 PBP: Brad Nessler PBP: Gene Deckerhoff 65.3 (19) Completion Pct. 62.3 (48) MEDIA COVERAGE 147.02 (38) Pass Efficiency 151.45 (27) Analyst: Gary Danielson Analyst: William Floyd Sideline: Jamie Erdahl Sideline: Tom Block 403.2 (64) Total Offense 379.6 (89) .865 (50) Red Zone Offense .902 (21) SEMINOLES RETURN TO POSTSEASON WITH TRIP TO EL PASO .563 (53) 4th Down Offense .563 (53) 244 (82) First Downs 220 (108) » Florida State makes its return to postseason play with its third trip to the Sun Bowl. The Seminoles appeared in 28.5 (71) Scoring Defense 32.1 (40) El Paso following the 1954 and 1966 seasons, and their 53 years between Sun Bowl trips is the 4th-longest gap between teams making multiple Sun Bowl appearances. -

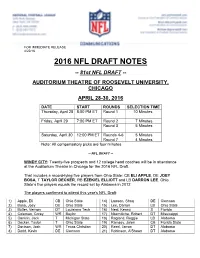

2016 Nfl Draft Notes

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 4/22/16 2016 NFL DRAFT NOTES -- 81st NFL DRAFT -- AUDITORIUM THEATRE OF ROOSEVELT UNIVERSITY, CHICAGO APRIL 28-30, 2016 DATE START ROUNDS SELECTION TIME Thursday, April 28 8:00 PM ET Round 1 10 Minutes Friday, April 29 7:00 PM ET Round 2 7 Minutes Round 3 5 Minutes Saturday, April 30 12:00 PM ET Rounds 4-6 5 Minutes Round 7 4 Minutes Note: All compensatory picks are four minutes -- NFL DRAFT -- WINDY CITY: Twenty-five prospects and 12 college head coaches will be in attendance at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago for the 2016 NFL Draft. That includes a record-tying five players from Ohio State: CB ELI APPLE, DE JOEY BOSA, T TAYLOR DECKER, RB EZEKIEL ELLIOTT and LB DARRON LEE. Ohio State’s five players equals the record set by Alabama in 2012. The players confirmed to attend this year’s NFL Draft: 1) Apple, Eli CB Ohio State 14) Lawson, Shaq DE Clemson 2) Bosa, Joey DE Ohio State 15) Lee, Darron LB Ohio State 3) Butler, Vernon DT Louisiana Tech 16) Neal, Keanu S Florida 4) Coleman, Corey WR Baylor 17) Nkemdiche, Robert DT Mississippi 5) Conklin, Jack T Michigan State 18) Ragland, Reggie LB Alabama 6) Decker, Taylor T Ohio State 19) Ramsey, Jalen CB Florida State 7) Doctson, Josh WR Texas Christian 20) Reed, Jarran DT Alabama 8) Dodd, Kevin DE Clemson 21) Robinson, A'Shawn DT Alabama 9) Elliott, Ezekiel RB Ohio State 22) Stanley, Ronnie T Notre Dame 10) Goff, Jared QB California 23) Treadwell, Laquon WR Mississippi 11) Hargreaves, Vernon CB Florida 24) Tunsil, Laremy T Mississippi 12) Jack, Myles LB UCLA 25) Wentz,