Modesty and Piety: Improving on the Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rebbe and the Yak

Hillel Halkin on King James: The Harold Bloom Version JEWISH REVIEW Volume 2, Number 3 Fall 2011 $6.95 OF BOOKS Alan Mintz The Rebbe and the Yak Ruth R. Wisse Yehudah Mirsky Adam Kirsch Moshe Halbertal The Faith of Reds On Law & Forgiveness Yehuda Amital Elli Fischer & Shai Secunda Footnote: the Movie! Ruth Gavison The Nation of Israel? Philip Getz Birthright & Diaspora PLUS Did Billie Holiday Sing Yo's Blues? Sermons & Anti-Sermons & MORE Editor Abraham Socher Publisher Eric Cohen The history of America — Senior Contributing Editor one fear, one monster, Allan Arkush Editorial Board at a time Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri “An unexpected guilty pleasure! Poole invites us Leora Batnitzky into an important and enlightening, if disturbing, Ruth Gavison conversation about the very real monsters that Moshe Halbertal inhabit the dark spaces of America’s past.” Hillel Halkin – J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira “A well informed, thoughtful, and indeed frightening Michael Walzer angle of vision to a compelling American desire to J. H.H. Weiler be entertained by the grotesque and the horrific.” Leon Wieseltier – Gary Laderman, Emory University Ruth R. Wisse Available in October at fine booksellers everywhere. Steven J. Zipperstein Assistant Editor Philip Getz Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Business Manager baylor university press Lori Dorr baylorpress.com Interns Kif Leswing Arielle Orenstein The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, An eloquent intellectual Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication of ideas and criticism published in Spring, history of the human Summer, Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 745 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1400, New York, NY 10151. -

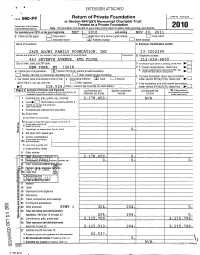

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

d I EXTENSION ATTACHED Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2010 Internal Revenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2010 , or tax year beginning DEC 1, 2010 and ending NOV 3 0, 2011 G Check all that apply. Initial return Initial return of a former public charity Ej Final return 0 Amended return ® Address chanae Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMI FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 13-3202295 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/swte B Telephone number 463 SEVENTH AVENUE , 4TH FLOOR 212-629-960 0 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here NEW YORK , NY 10 018 D 1- Foreign organizations, check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation charitable Other taxable foundation Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt trust 0 private E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) = Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 111114 218 5 2 4 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507 b 1 B , check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b) (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received 2 , 178 , 450. -

JUDAICA LIST [email protected] List 2, July 2014 75 Items Including PH: 44 208 455 9139 Anglo-Judaica, FAX: 44 208 922 5008 Zionism and Antiquarian Books

FISHBURN BOOKS www.fishburnbooks.com JUDAICA LIST [email protected] List 2, July 2014 75 Items including PH: 44 208 455 9139 Anglo-Judaica, FAX: 44 208 922 5008 Zionism and Antiquarian books ITEM NO 51 – FIDDLER ON THE ROOF FILM POSTER £125 ZIONISM , PALESTINE MANDATE AND ISRAEL 1. ANTI -TUBERCULOSIS LEAGUE OF PALESTINE = LIGA LE -MILKHAMA -BE - SHAHAFAT BE -ERETS YISRAEL Jerusalem, Anti-Tuberculosis League of Palestine 1930-40 18cm, single sheet folded to form 8p., ill., text in English, alternative title in English, very good condition. [ref: 13008 ] £45 2. NORDAU , MAX . POSTCARD – PORTRAIT OF MAX NORDAU SIGNED BY HIM WITH A SHORT NOTE DATED 1907 Max Nordau (1849 – 1923) was a Zionist leader, physician, author, and social critic. He was a co- founder of the World Zionist Organization together with Theodor Herzl, and president or vice president of several Zionist congresses. [ref: 16069 ] £375 3. YIZKOR... TMUNOT VE -TOLDOT 18 QEDOSHEI NISSAN 5696 Tel-Aviv, A. Mozes 1936? Original wrappers, 27cm, 6pp, text in Hebrew, black and white photos, soiling to first two pages, creasing throughout. Pamphlet commemorating the first victims of Arab Revolt. Includes a portrait and short life story of each of the victims. Photo of Israel Hazan on the front cover. [ref: 11286 ] £125 4. HECHALUTZ . - HOW JEWISH YOUTH IN BRITAIN REGAIN NEW LIFE ON THE LAND . London Hechalutz [1942] Original wrappers, 24 cm, 15 pp, text in English, illustrated. Photos of Hechalutz in Palestine and in Kent. One staple is missing. [ref: 15620 ] £100 5. CLASSIFIED PALESTINE SONGS . NUMBER 1. CAMP ISSUE Jerusalem, The Overseas Youth Department of the Head Office of the Jewish National Fund 1942 Original wrappers, 30cm, 18pp, text in English and Hebrew, illustrated, good condition Includes note charts, Hebrew text, transliteration and English translation of all the songs. -

The Corona Ushpizin

אושפיזי קורונה THE CORONA USHPIZIN Rabbi Jonathan Schwartz PsyD Congregation Adath Israel of the JEC Elizabeth/Hillside, NJ סוכות תשפא Corona Ushpizin Rabbi Dr Jonathan Schwartz 12 Tishrei 5781 September 30, 2020 משה תקן להם לישראל שיהו שואלים ודורשים בענינו של יום הלכות פסח בפסח הלכות עצרת בעצרת הלכות חג בחג Dear Friends: The Talmud (Megillah 32b) notes that Moshe Rabbeinu established a learning schedule that included both Halachic and Aggadic lessons for each holiday on the holiday itself. Indeed, it is not only the experience of the ceremonies of the Chag that make them exciting. Rather, when we analyze, consider and discuss why we do what we do when we do it, we become more aware of the purposes of the Mitzvos and the holiday and become closer to Hashem in the process. In the days of old, the public shiurim of Yom Tov were a major part of the celebration. The give and take the part of the day for Hashem, it set a tone – חצי לה' enhanced not only the part of the day identified as the half of the day set aside for celebration in eating and enjoyment of a חצי לכם for the other half, the different nature. Meals could be enjoyed where conversation would surround “what the Rabbi spoke about” and expansion on those ideas would be shared and discussed with everyone present, each at his or her own level. Unfortunately, with the difficulties presented by the current COVID-19 pandemic, many might not be able to make it to Shul, many Rabbis might not be able to present the same Derashos and Shiurim to all the different minyanim under their auspices. -

1 American Victims of the 1929 Hebron Massacre Dr. Yitzchok

American Victims Of The 1929 Hebron Massacre Dr. Yitzchok Levine Department of Mathematical Sciences Stevens Institute of Technology Hoboken, NJ 07030 [email protected] Introduction On August 27, 1929 The New York Times ran a front page article under the banner 8 AMERICANS LISTED IN 70 HEBRON DEAD Attack on Rabbinical College was Savage – 18 Killed in Banker’s House WOMEN AND CHILDREN SLAIN The headline was, of course, referring to the infamous and unprovoked Hebron Massacre that Arabs perpetrated on innocent Jews on August 24. Many of those killed on this Shabbos were students studying in the branch of the Slabodka Yeshiva then located in Hebron. In 1924 the Lithuanian government tried to draft into the army the majority of students studying in the Slabodka Yeshiva. This, of course, threatened the very existence of the Yeshiva. Since Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein, the Rosh Yeshiva, was in America at that time, Rabbi Yechezkel Sarna tried to have the decree averted, but to no avail. After consulting Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, known as the Alter of Slabodka, it was decided to transfer the yeshiva to Eretz Yisroel. The Alter sent a telegram to Rabbi Epstein asking if he approved of the plan. Rabbi Epstein wired back his consent promising to make every effort to raise the funds necessary for the yeshiva's relocation. That same year the Alter sent Rabbi Sarna to Eretz Yisroel to choose a site for the yeshiva and to coordinate its establishment there. He was also charged with securing visas for the students. After evaluating various options, Rabbi Sarna chose the city of Hebron as the yeshiva's new home. -

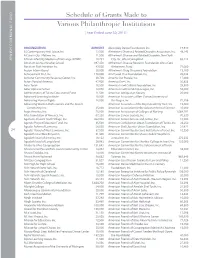

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

SVEKSNA: Our Town

SVEKSNA:U Our Town This article is dedicated to the memory of my Grandfather Zacharia Marcus, who came from Sveksna; and to my cousins: Jack Marcus, Daniel Marcus, Marcia Partridge, Mark Marcus, to their children and of course to my Daughters and their children: with hope that we will all always remember our common background with honor and love. To Allison, Marcia’s daughter, the biggest wedding present that I can give you, is to share my love for our Family Heritage with you. Esther (Herschman) Rechtschafner Kibbutz Ein Zurim 79510 ISRAEL 08 8588281 [email protected] Copyright © 2004 Esther (Herschman) Rechtschafner 1 TABLEU OF CONTENTS U PU age U INTRODUCTION 3 THE JEWS OF LITHUANIA 5 HISTORY 5 CULTURAL LIFE 14 ENLIGHTENMENT 19 ZIONISM 21 SOCIALISM 24 INFLUENCE 25 SVEKSNA 26 GEOGRAPHY 26 HISTORY 27 JEWISH HISTORY 30 THE HOLOCAUST 38 AFTER THE HOLOCAUST 47 APPENDICES 52 APPENDIX 1- MAP OF LITHUANIA 52 APPENDIX 2- MAP OF SVEKSNA AREA 53 APPENDIX 3- THE JEWISH POPULATION IN LITHUANIA 54 APPENDIX 4-THE POPULATION/ JEWISH POPULATION OF SVEKSNA 55 APPENDIX 5- SHOPS IN SVEKSNA 56 CONCLUSION 57 BIBLIOGRAPHY 59 2 INTRODU UCTION During the past few years I have written articles about the places in Eastern Europe that my Grandparents came from. 1 Now the time has come for me to try to write about Sveksna, the town in Lithuania that my Maternal Grandfather ZACHARIAU MARCUS,U who I loved so much, came from. I hope to succeed here in honoring the memory of the Jews of this town; and thereby the memory of my Grandfather. -

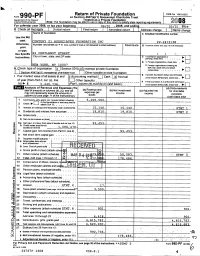

Return of Private Foundation

hilis, Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form• 990-PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust I 008 Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service Note : The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2008, or tax year beg inning 06 / 01 r 2008 , and ending 05 / 31 , 2009 G Check all that apply initial return Final return Amended return T_Address chance I Nama rh..,.,o Name of foundation A Employer Identification number Use the IRS label. CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 Otherwise , Number and street ( or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see page 10 of to vebucbore) print or type. See Specific 22 CORTLANDT STREET _ Instructions . City or town , state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending , check here • • . D 1. Foreign organizations , check here , NEW YORK , NY 10007 2. Foreign organizations meeting the co ones . here and attach H Check type of organization. X Section 501 ( c 3 lucom exempt private foundation cam p utation Section 4947 ( a)( 1 ) nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accounting method : Cash X] Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A) , check here . 0. El of year (from Part ll, col. (c), line Other (specify) _ _ _ _ __________________ F If the foundation Is in afi0-monthtermination 16) ' $ 5 , 440 , 73 6. -

The Flourishing of Higher Jewish Learning for Women

www.jcpa.org No. 429 26 Nisan 5760 / 1 May 2000 THE FLOURISHING OF HIGHER JEWISH LEARNING FOR WOMEN Rochelle Furstenberg Hundreds of Women Scholars / The Hafetz Haim Supports Women's Study in 1918 / Jewish Education Beyond High School / Nechama Leibowitz / Contemporary Jewish Studies for Women / The Ideology of Women's Study / Rabbinical Court Advocates / Women as Rabbinic Judges? / Halakhic Advisors / Women as Spiritual Leaders / Women's Unique Approach to Study This is written in memory of Daniel Elazar, whose sweet intelligence enriched the lives of all who touched him. His deep connectedness to Am Yisrael, his perception of human nature and the workings of the polity, his warmth, and yearning for justice and truth beyond the commonly accepted academic truths, made him a friend and mentor. Each time I spoke to him I came away with new insights about life and society, particularly Israeli society. * * * Hundreds of Women Scholars A revolution is taking place. Yet most of the orthodox community denies that it is a revolution. They look with wonder and pride at what is being created, and yet downplay the revolutionary aspect of this feminist development. To some extent, this soft-pedaling of the revolutionary aspect of women's study of Judaism is tactical. The leaders of the revolution are fearful of arousing the opposition of the conservative elements of the religious Establishment whom they need for both financial and institutional support. But most of all, revolution runs counter to the self-image of most of the orthodox women involved in women's study. Revolution is identified with the breakdown of tradition, and these women cherish and want to promote the tradition. -

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2017 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT American Civil Liberties Union Foundation of 18 Corp. d/b/a Ahavat Torah of Short Hills 73,000 Florida, Inc. 28,000 180 Turning Lives Around, Inc. 100,000 American Civil Liberties Union Foundation, Inc. 284,328 9 Dots Community Learning Center 36,000 American Committee for Shaare Zedek Hospital A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 58,717 in Jerusalem, Inc. 498,449 JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Joshua Heschel School 1,410,430 American Committee for the Weizmann Institute Academy in Manayunk, Inc. 37,425 of Science, Inc. 183,125 Accion International 30,000 American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Achievement First, Inc. 150,000 Research 130,000 Ackerman Institute for the Family 55,250 American Freedom Defense Initiative 50,000 ACLU Foundation of Southern California 258,830 American Friends of Alyn Hospital, Inc. 46,034 Actors Fund of America 186,200 American Friends of Amaleh Shel Torah, Inc. 29,610 Adirondack Council, Inc. 27,200 American Friends of Aram Soba 54,181 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 32,500 American Friends of Ateret Cohanem, Inc. 37,056 Advanced Learning Institute 106,000 American Friends of Bat Ayin Yeshiva 39,500 African Wildlife Foundation 25,000 American Friends of Batsheva Dance Company, Inc. 87,834 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 78,600 American Friends of Beit Hatfutsot 1,843,500 Agahozo-Shalom Youth Village, Inc. 610,790 American Friends of Beit Issie Shapiro, Inc. 46,876 Agenda Project Education Fund, Inc. 46,250 American Friends of Beit Morasha 40,100 Agudas Yisroel of West Lawrence, Inc. -

Eikev 5781; Tu B’Av Shabbat

July 30, 2021; 21 Av 5781 Potomac Torah Study Center Vol. 8 #41, July 30, 2021; 21 Av 5781; Eikev 5781; Tu B’Av Shabbat .. NOTE: Devrei Torah presented weekly in Loving Memory of Rabbi Leonard S. Cahan z”l, Rabbi Emeritus of Congregation Har Shalom, who started me on my road to learning 50 years ago and was our family Rebbe and close friend until his untimely death. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Devrei Torah are now Available for Download (normally by noon on Fridays) from www.PotomacTorah.org. Thanks to Bill Landau for hosting the Devrei Torah. New: a limited number of copies of the first attachment will now be available at Beth Sholom on the Shabbas table! __________________________________________________________________________________ Dedicated in loving memory of Sidney Glashofer, Yisrael ben Yaakov, husband of Miriam Glashofer and father of Paul Glashofer. Heartfelt condolences to Paul, his wife Sara, and family. ____________________________________________________________________________________ Each parsha in Sefer Devarim has a special theme or focus. In Eikev, the focus is on the land of Israel, especially in connection with Avraham Avinu. God repeatedly tests Avraham until after the Akeidah, He promises Avraham many descendants and the land of Israel – “eikev” (because) Avraham did not withhold even his most treasured possession, his beloved son Yitzhak. Rabbi David Fohrman’s colleagues at alephbeta.org explain Moshe’s warning. The “eikev” connection requires that Jews keep God’s mitzvot, undertake periodic tests from God, and remember that the land and its benefits are a gift to Jews only as long as we realize the source and express appreciation to God for His blessings. -

Fine Judaica: Printed Books, Manuscripts, Holy Land Maps & Ceremonial Objects, to Be Held June 23Rd, 2016

F i n e J u d a i C a . printed booKs, manusCripts, holy land maps & Ceremonial obJeCts K e s t e n b au m & C om pa n y thursday, Ju ne 23r d, 2016 K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny . Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art A Lot 147 Catalogue of F i n e J u d a i C a . PRINTED BOOK S, MANUSCRIPTS, HOLY LAND MAPS & CEREMONIAL OBJECTS INCLUDING: Important Manuscripts by The Sinzheim-Auerbach Rabbinic Dynasty Deaccessions from the Rare Book Room of The Hebrew Theological College, Skokie, Ill. Historic Chabad-related Documents Formerly the Property of the late Sam Kramer, Esq. Autograph Letters from the Collection of the late Stuart S. Elenko Holy Land Maps & Travel Books Twentieth-Century Ceremonial Objects The Collection of the late Stanley S. Batkin, Scarsdale, NY ——— To be Offered for Sale by Auction, Thursday, 23rd June, 2016 at 3:00 pm precisely ——— Viewing Beforehand: Sunday, 19th June - 12:00 pm - 6:00 pm Monday, 20th June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Tuesday, 21st June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Wednesday, 22nd June - 10:00 am - 6:00 pm No Viewing on the Day of Sale This Sale may be referred to as: “Consistoire” Sale Number Sixty Nine Illustrated Catalogues: $38 (US) * $45 (Overseas) KESTENBAUM & COMPANY Auctioneers of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Fine Art . 242 West 30th Street, 12th Floor, New York, NY 10001 • Tel: 212 366-1197 • Fax: 212 366-1368 E-mail: [email protected] • World Wide Web Site: www.Kestenbaum.net K est e n bau m & C o m pa ny .