SVEKSNA: Our Town

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust

Ezra’s Archives | 77 Strategies of Survival: Lithuanian Jews and the Holocaust Taly Matiteyahu On the eve of World War II, Lithuanian Jewry numbered approximately 220,000. In June 1941, the war between Germany and the Soviet Union began. Within days, Germany had occupied the entirety of Lithuania. By the end of 1941, only about 43,500 Lithuanian Jews (19.7 percent of the prewar population) remained alive, the majority of whom were kept in four ghettos (Vilnius, Kaunas, Siauliai, Svencionys). Of these 43,500 Jews, approximately 13,000 survived the war. Ultimately, it is estimated that 94 percent of Lithuanian Jewry died during the Holocaust, a percentage higher than in any other occupied Eastern European country.1 Stories of Lithuanian towns and the manner in which Lithuanian Jews responded to the genocide have been overlooked as the perpetrator- focused version of history examines only the consequences of the Holocaust. Through a study utilizing both historical analysis and testimonial information, I seek to reconstruct the histories of Lithuanian Jewish communities of smaller towns to further understand the survival strategies of their inhabitants. I examined a variety of sources, ranging from scholarly studies to government-issued pamphlets, written testimonies and video testimonials. My project centers on a collection of 1 Population estimates for Lithuanian Jews range from 200,000 to 250,000, percentages of those killed during Nazi occupation range from 90 percent to 95 percent, and approximations of the number of survivors range from 8,000 to 20,000. Here I use estimates provided by Dov Levin, a prominent international scholar of Eastern European Jewish history, in the Introduction to Preserving Our Litvak Heritage: A History of 31 Jewish Communities in Lithuania. -

The Migration of Lithuanian Jews to the United States, 1880 – 1918, and the Decisions Involved in the Process, Exemplified by Five Individual Migration Stories

Nathan T. Shapiro Hofstra University Department of Global Studies and Geography The Migration of Lithuanian Jews to the United States, 1880 – 1918, and the Decisions Involved in the Process, Exemplified by Five Individual Migration Stories Honors Thesis in Geography Advisor: Dr. Kari B. Jensen Shapiro 1 Table of Contents Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 2 Jews in Lita and Reasons for Their Emigration According to the Literature ..................... 5 Migration Theory .............................................................................................................. 11 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 14 Case studies: Five Personal Migration Stories .................................................................. 16 Concluding Remarks ......................................................................................................... 35 Endnote ............................................................................................................................. 39 Bibliography ..................................................................................................................... 40 Appendix ........................................................................................................................... 43 Figure 1: Europe 1871 ...................................................................................................... -

The Rebbe and the Yak

Hillel Halkin on King James: The Harold Bloom Version JEWISH REVIEW Volume 2, Number 3 Fall 2011 $6.95 OF BOOKS Alan Mintz The Rebbe and the Yak Ruth R. Wisse Yehudah Mirsky Adam Kirsch Moshe Halbertal The Faith of Reds On Law & Forgiveness Yehuda Amital Elli Fischer & Shai Secunda Footnote: the Movie! Ruth Gavison The Nation of Israel? Philip Getz Birthright & Diaspora PLUS Did Billie Holiday Sing Yo's Blues? Sermons & Anti-Sermons & MORE Editor Abraham Socher Publisher Eric Cohen The history of America — Senior Contributing Editor one fear, one monster, Allan Arkush Editorial Board at a time Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri “An unexpected guilty pleasure! Poole invites us Leora Batnitzky into an important and enlightening, if disturbing, Ruth Gavison conversation about the very real monsters that Moshe Halbertal inhabit the dark spaces of America’s past.” Hillel Halkin – J. Gordon Melton, Institute for the Study of American Religion Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira “A well informed, thoughtful, and indeed frightening Michael Walzer angle of vision to a compelling American desire to J. H.H. Weiler be entertained by the grotesque and the horrific.” Leon Wieseltier – Gary Laderman, Emory University Ruth R. Wisse Available in October at fine booksellers everywhere. Steven J. Zipperstein Assistant Editor Philip Getz Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Business Manager baylor university press Lori Dorr baylorpress.com Interns Kif Leswing Arielle Orenstein The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, An eloquent intellectual Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication of ideas and criticism published in Spring, history of the human Summer, Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 745 Fifth Avenue, Suite 1400, New York, NY 10151. -

Researching Your Lithuanian Roots

RESEARCHING YOUR LITHUANIAN ROOTS Judy Baston [email protected] Since its founding 20 years ago, LitvakSIG’s translation activities have taken place through geographic- specific Research Groups whose primary purpose is to identify, collect and translate data from available records for Lithuania. A number of towns now in Belarus and Poland but with records in Lithuanian Archives also fall under our aegis. Looking forward, LitvakSIG will be translating more records from the Lithuanian State Central Archives, including country-wide lists such as: Emigration to Eretz Israel; Evacuees to the USSR during World War II; Jewish Volunteers in the Lithuanian Army; JDC Lithuanian Survivors List. LitvakSIG is an independent organization whose database and discussion group are hosted by JewishGen. Each organization has its own, separate administrative and fundraising structure. How to find out what records exist for your towns * In LitvakSIG, towns are organized into District Research Groups for the purpose of getting records translated. To find out what District your town is in, download and check the LitvakSIG Shtetl List It will show you the current spelling of the town and what District the town is in. https://www.litvaksig.org/information-and-tools/shtetls/ * On the website for Miriam Weiner’s Routes to Roots Foundation, search the archival database for the town and also for the Uyezd (District) that the town is in. These searches will provide information on what records exist and what archives they are in. http://www.rtrfoundation.org/search.php * Browse the Index of Records in the Kaunas Regional Archive and the Inventory of Jewish Vital Records in the Lithuanian State Historical Archives (LVIA), which are on the LitvakSIG Members Page. -

Modesty and Piety: Improving on the Past

Modesty and Piety: Improving on the Past Modesty and Piety: Improving on the Past by: Michael K. Silber The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The well known “coat of arms” of the priestly Rapaport family first appeared as a colophon at the end of Avraham Menachem Rapa of Porto’s Mincha Belulah (Verona, 1594), fol. 207b, readily at HebrewBooks.org (here). Instead of a motto, a banner proclaimed the author’s name above and below the shield which featured a pair of hands raised in priestly benediction in the upper half, while below was depicted a crow (Rabe in German) on a branch, a reference to the author’s family name. The shield is flanked by two heraldic supporters, and this is what interests us here. The supporters feature two female torsos rampant facing away from the shield. They are nude from the waist up. It was by no means rare to encounter nude women in Hebrew books between the sixteenth and the early eighteenth centuries, even prominently displayed on the covers (Adam accompanied at times by a buxom Eve is a ready example). But no doubt such nudity proves unsettling to the Orthodox public nowadays. Benjamin Shlomo Hamburger’s recently published magisterial three volume history, Ha-Yeshiva ha-Rama bi-Fiorda (Bnei Brak, 5770) is a rich, learned study by one who has dedicated many scholarly books to the heritage of German Jewry. The volumes are noteworthy also for their rich illustrations, but one in particular catches the eye. A chapter dedicated to Baruch Kahana Rapaport who served for many years as rabbi of Fürth (1711-1746), reproduces, as many a study on the Rapaports, the “coat of arms” fromMincha Belulah (volume 1, page 390). -

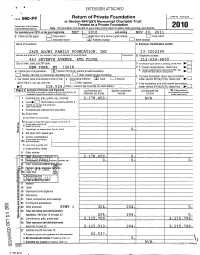

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

d I EXTENSION ATTACHED Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2010 Internal Revenue Service Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2010 , or tax year beginning DEC 1, 2010 and ending NOV 3 0, 2011 G Check all that apply. Initial return Initial return of a former public charity Ej Final return 0 Amended return ® Address chanae Name change Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMI FAMILY FOUNDATION INC 13-3202295 Number and street (or P O box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/swte B Telephone number 463 SEVENTH AVENUE , 4TH FLOOR 212-629-960 0 City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here NEW YORK , NY 10 018 D 1- Foreign organizations, check here 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation charitable Other taxable foundation Section 4947(a )( 1 ) nonexem pt trust 0 private E If p rivate foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: ® Cash 0 Accrual under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col. (c), line 16) = Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 111114 218 5 2 4 . (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis.) under section 507 b 1 B , check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net ( d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns (b) (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a)) expenses per books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received 2 , 178 , 450. -

The Lithuanian Jewish Community of Telšiai

The Lithuanian Jewish Community of Telšiai By Philip S. Shapiro1 Introduction This work had its genesis in an initiative of the “Alka” Samogitian Museum, which has undertaken projects to recover for Lithuanians the true history of the Jews who lived side-by-side with their ancestors. Several years ago, the Museum received a copy of the 500-plus-page “yizkor” (memorial) book for the Jewish community of Telšiai,2 which was printed in 1984.3 The yizkor book is a collection of facts and personal memories of those who had lived in Telšiai before or at the beginning of the Second World War. Most of the articles are written in Hebrew or Yiddish, but the Museum was determined to unlock the information that the book contained. Without any external prompting, the Museum embarked upon an ambitious project to create a Lithuanian version of The Telshe Book. As part of that project, the Museum organized this conference to discuss The Telshe Book and the Jewish community of Telšiai. This project is of great importance to Lithuania. Since Jews constituted about half of the population of most towns in provincial Lithuania in the 19th Century, a Lithuanian translation of the book will not only give Lithuanian readers a view of Jewish life in Telšiai but also a better knowledge of the town’s history, which is our common heritage. The first part of this article discusses my grandfather, Dov Ber Shapiro, who was born in 1883 in Kamajai, in the Rokiškis region, and attended the Telshe Yeshiva before emigrating in 1903 to the United States, where he was known as “Benjamin” Shapiro. -

JUDAICA LIST [email protected] List 2, July 2014 75 Items Including PH: 44 208 455 9139 Anglo-Judaica, FAX: 44 208 922 5008 Zionism and Antiquarian Books

FISHBURN BOOKS www.fishburnbooks.com JUDAICA LIST [email protected] List 2, July 2014 75 Items including PH: 44 208 455 9139 Anglo-Judaica, FAX: 44 208 922 5008 Zionism and Antiquarian books ITEM NO 51 – FIDDLER ON THE ROOF FILM POSTER £125 ZIONISM , PALESTINE MANDATE AND ISRAEL 1. ANTI -TUBERCULOSIS LEAGUE OF PALESTINE = LIGA LE -MILKHAMA -BE - SHAHAFAT BE -ERETS YISRAEL Jerusalem, Anti-Tuberculosis League of Palestine 1930-40 18cm, single sheet folded to form 8p., ill., text in English, alternative title in English, very good condition. [ref: 13008 ] £45 2. NORDAU , MAX . POSTCARD – PORTRAIT OF MAX NORDAU SIGNED BY HIM WITH A SHORT NOTE DATED 1907 Max Nordau (1849 – 1923) was a Zionist leader, physician, author, and social critic. He was a co- founder of the World Zionist Organization together with Theodor Herzl, and president or vice president of several Zionist congresses. [ref: 16069 ] £375 3. YIZKOR... TMUNOT VE -TOLDOT 18 QEDOSHEI NISSAN 5696 Tel-Aviv, A. Mozes 1936? Original wrappers, 27cm, 6pp, text in Hebrew, black and white photos, soiling to first two pages, creasing throughout. Pamphlet commemorating the first victims of Arab Revolt. Includes a portrait and short life story of each of the victims. Photo of Israel Hazan on the front cover. [ref: 11286 ] £125 4. HECHALUTZ . - HOW JEWISH YOUTH IN BRITAIN REGAIN NEW LIFE ON THE LAND . London Hechalutz [1942] Original wrappers, 24 cm, 15 pp, text in English, illustrated. Photos of Hechalutz in Palestine and in Kent. One staple is missing. [ref: 15620 ] £100 5. CLASSIFIED PALESTINE SONGS . NUMBER 1. CAMP ISSUE Jerusalem, The Overseas Youth Department of the Head Office of the Jewish National Fund 1942 Original wrappers, 30cm, 18pp, text in English and Hebrew, illustrated, good condition Includes note charts, Hebrew text, transliteration and English translation of all the songs. -

The Corona Ushpizin

אושפיזי קורונה THE CORONA USHPIZIN Rabbi Jonathan Schwartz PsyD Congregation Adath Israel of the JEC Elizabeth/Hillside, NJ סוכות תשפא Corona Ushpizin Rabbi Dr Jonathan Schwartz 12 Tishrei 5781 September 30, 2020 משה תקן להם לישראל שיהו שואלים ודורשים בענינו של יום הלכות פסח בפסח הלכות עצרת בעצרת הלכות חג בחג Dear Friends: The Talmud (Megillah 32b) notes that Moshe Rabbeinu established a learning schedule that included both Halachic and Aggadic lessons for each holiday on the holiday itself. Indeed, it is not only the experience of the ceremonies of the Chag that make them exciting. Rather, when we analyze, consider and discuss why we do what we do when we do it, we become more aware of the purposes of the Mitzvos and the holiday and become closer to Hashem in the process. In the days of old, the public shiurim of Yom Tov were a major part of the celebration. The give and take the part of the day for Hashem, it set a tone – חצי לה' enhanced not only the part of the day identified as the half of the day set aside for celebration in eating and enjoyment of a חצי לכם for the other half, the different nature. Meals could be enjoyed where conversation would surround “what the Rabbi spoke about” and expansion on those ideas would be shared and discussed with everyone present, each at his or her own level. Unfortunately, with the difficulties presented by the current COVID-19 pandemic, many might not be able to make it to Shul, many Rabbis might not be able to present the same Derashos and Shiurim to all the different minyanim under their auspices. -

1 American Victims of the 1929 Hebron Massacre Dr. Yitzchok

American Victims Of The 1929 Hebron Massacre Dr. Yitzchok Levine Department of Mathematical Sciences Stevens Institute of Technology Hoboken, NJ 07030 [email protected] Introduction On August 27, 1929 The New York Times ran a front page article under the banner 8 AMERICANS LISTED IN 70 HEBRON DEAD Attack on Rabbinical College was Savage – 18 Killed in Banker’s House WOMEN AND CHILDREN SLAIN The headline was, of course, referring to the infamous and unprovoked Hebron Massacre that Arabs perpetrated on innocent Jews on August 24. Many of those killed on this Shabbos were students studying in the branch of the Slabodka Yeshiva then located in Hebron. In 1924 the Lithuanian government tried to draft into the army the majority of students studying in the Slabodka Yeshiva. This, of course, threatened the very existence of the Yeshiva. Since Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Epstein, the Rosh Yeshiva, was in America at that time, Rabbi Yechezkel Sarna tried to have the decree averted, but to no avail. After consulting Rabbi Nosson Tzvi Finkel, known as the Alter of Slabodka, it was decided to transfer the yeshiva to Eretz Yisroel. The Alter sent a telegram to Rabbi Epstein asking if he approved of the plan. Rabbi Epstein wired back his consent promising to make every effort to raise the funds necessary for the yeshiva's relocation. That same year the Alter sent Rabbi Sarna to Eretz Yisroel to choose a site for the yeshiva and to coordinate its establishment there. He was also charged with securing visas for the students. After evaluating various options, Rabbi Sarna chose the city of Hebron as the yeshiva's new home. -

Lithuania and the Jews the Holocaust Chapter

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Lithuania and the Jews The Holocaust Chapter Symposium Presentations W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Lithuania and the Jews The Holocaust Chapter Symposium Presentations CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2004 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. First printing, July 2005 Copyright © 2005 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Contents Foreword.......................................................................................................................................... i Paul A. Shapiro and Carl J. Rheins Lithuanian Collaboration in the “Final Solution”: Motivations and Case Studies........................1 Michael MacQueen Key Aspects of German Anti-Jewish Policy...................................................................................17 Jürgen Matthäus Jewish Cultural Life in the Vilna Ghetto .......................................................................................33 David G. Roskies Appendix: Biographies of Contributors.........................................................................................45 Foreword Centuries of intellectual, religious, and cultural achievements distinguished Lithuania as a uniquely important center of traditional Jewish arts and learning. The Jewish community -

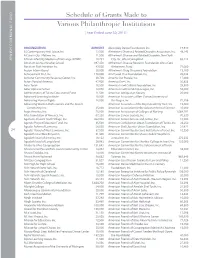

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc.