Chronicling the Recorded Legacy of Motown's Golden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Young Americans to Emotional Rescue: Selected Meetings

YOUNG AMERICANS TO EMOTIONAL RESCUE: SELECTING MEETINGS BETWEEN DISCO AND ROCK, 1975-1980 Daniel Kavka A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC August 2010 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Katherine Meizel © 2010 Daniel Kavka All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Disco-rock, composed of disco-influenced recordings by rock artists, was a sub-genre of both disco and rock in the 1970s. Seminal recordings included: David Bowie’s Young Americans; The Rolling Stones’ “Hot Stuff,” “Miss You,” “Dance Pt.1,” and “Emotional Rescue”; KISS’s “Strutter ’78,” and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You”; Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy“; and Elton John’s Thom Bell Sessions and Victim of Love. Though disco-rock was a great commercial success during the disco era, it has received limited acknowledgement in post-disco scholarship. This thesis addresses the lack of existing scholarship pertaining to disco-rock. It examines both disco and disco-rock as products of cultural shifts during the 1970s. Disco was linked to the emergence of underground dance clubs in New York City, while disco-rock resulted from the increased mainstream visibility of disco culture during the mid seventies, as well as rock musicians’ exposure to disco music. My thesis argues for the study of a genre (disco-rock) that has been dismissed as inauthentic and commercial, a trend common to popular music discourse, and one that is linked to previous debates regarding the social value of pop music. -

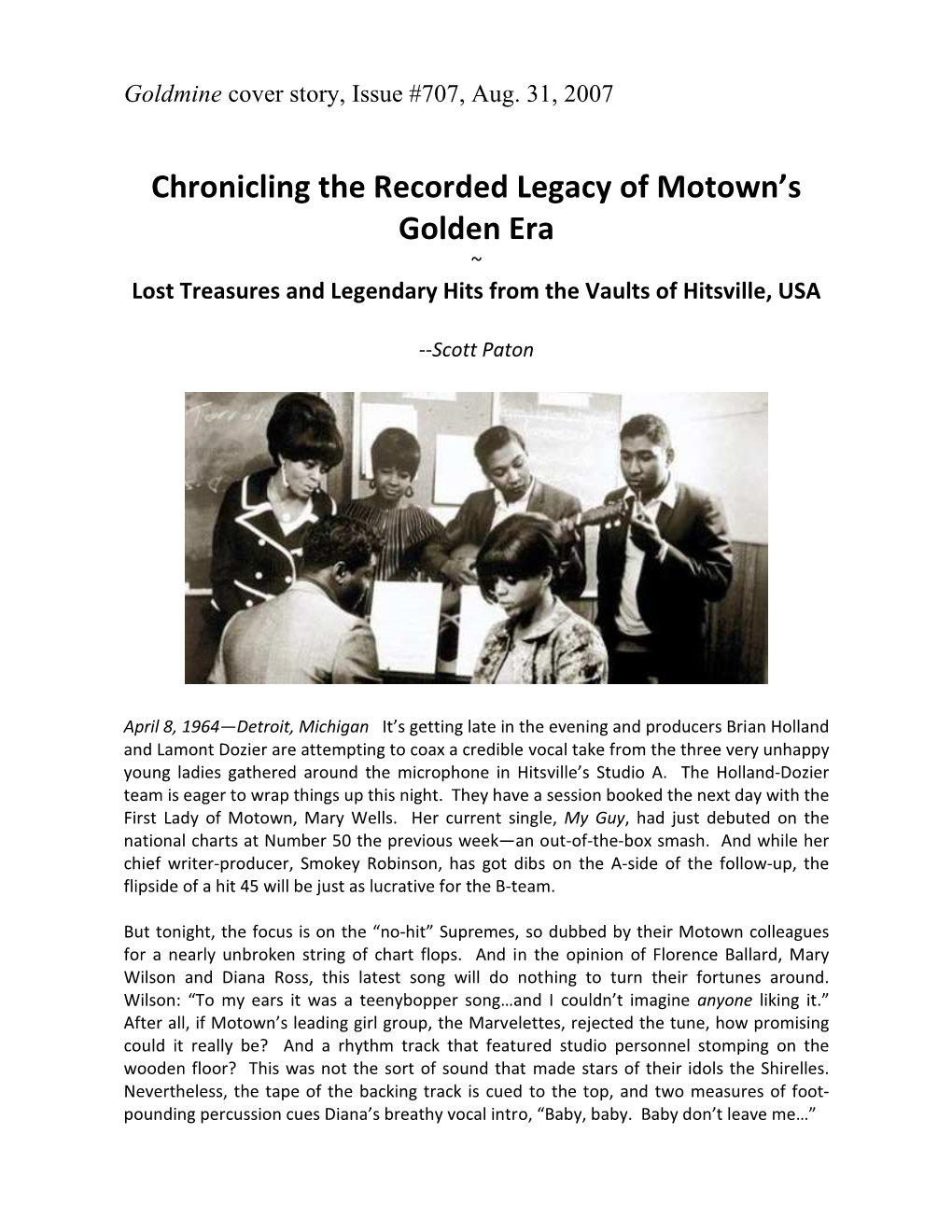

Marvin Gaye As Vocal Composer 63 Andrew Flory

Sounding Out Pop Analytical Essays in Popular Music Edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2010 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2013 2012 2011 2010 4321 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sounding out pop : analytical essays in popular music / edited by Mark Spicer and John Covach. p. cm. — (Tracking pop) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-472-11505-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-0-472-03400-0 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Popular music—History and criticism. 2. Popular music— Analysis, appreciation. I. Spicer, Mark Stuart. II. Covach, John Rudolph. ML3470.S635 2010 781.64—dc22 2009050341 Contents Preface vii Acknowledgments xi 1 Leiber and Stoller, the Coasters, and the “Dramatic AABA” Form 1 john covach 2 “Only the Lonely” Roy Orbison’s Sweet West Texas Style 18 albin zak 3 Ego and Alter Ego Artistic Interaction between Bob Dylan and Roger McGuinn 42 james grier 4 Marvin Gaye as Vocal Composer 63 andrew flory 5 A Study of Maximally Smooth Voice Leading in the Mid-1970s Music of Genesis 99 kevin holm-hudson 6 “Reggatta de Blanc” Analyzing -

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (Guest Post)*

“My Girl”—The Temptations (1964) Added to the National Registry: 2017 Essay by Mark Ribowsky (guest post)* The Temptations, c. 1964 The Temptations’ 1964 recording of “My Girl” came at a critical confluence for the group, the Motown label, and a culture roiling with the first waves of the British invasion of popular music. The five-man cell of disparate souls, later to be codified by black disc jockeys as the “tall, tan, talented, titillating, tempting Temptations,” had been knocking around Motown’s corridors and studio for three years, cutting six failed singles before finally scoring on the charts that year with Smokey Robinson’s cleverly spunky “The Way You Do the Things You Do” that winter. It rose to number 11 on the pop chart and to the top of the R&B chart, an important marker on the music landscape altered by the Beatles’ conquest of America that year. Having Smokey to guide them was incalculably advantageous. Berry Gordy, the former street hustler who had founded Motown as a conduit for Detroit’s inner-city voices in 1959, invested a lot of trust in the baby-faced Robinson, who as front man of the Miracles delivered the company’s seminal number one R&B hit and million-selling single, “Shop Around.” Four years later, in 1964, he wrote and produced Mary Wells’ “My Guy,” Motown’s second number one pop hit. Gordy conquered the black urban market but craved the broader white pop audience. The Temptations were riders on that train. Formed in 1959 by Otis Williams, a leather-jacketed street singer, their original lineup consisted of Williams, Elbridge “Al” Bryant, bass singer Melvin Franklin and tenors Eddie Kendricks and Paul Williams. -

Aaamc Issue 9 Chrono

of renowned rhythm and blues artists from this same time period lip-synch- ing to their hit recordings. These three aaamc mission: collections provide primary source The AAAMC is devoted to the collection, materials for researchers and students preservation, and dissemination of materi- and, thus, are invaluable additions to als for the purpose of research and study of our growing body of materials on African American music and culture. African American music and popular www.indiana.edu/~aaamc culture. The Archives has begun analyzing data from the project Black Music in Dutch Culture by annotating video No. 9, Fall 2004 recordings made during field research conducted in the Netherlands from 1998–2003. This research documents IN THIS ISSUE: the performance of African American music by Dutch musicians and the Letter ways this music has been integrated into the fabric of Dutch culture. The • From the Desk of the Director ...........................1 “The legacy of Ray In the Vault Charles is a reminder • Donations .............................1 of the importance of documenting and • Featured Collections: preserving the Nelson George .................2 achievements of Phyl Garland ....................2 creative artists and making this Arizona Dranes.................5 information available to students, Events researchers, Tribute.................................3 performers, and the • Ray Charles general public.” 1930-2004 photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Collection) photo by Beverly Parker (Nelson George Visiting Scholars reminder of the importance of docu- annotation component of this project is • Scot Brown ......................4 From the Desk menting and preserving the achieve- part of a joint initiative of Indiana of the Director ments of creative artists and making University and the University of this information available to students, Michigan that is funded by the On June 10, 2004, the world lost a researchers, performers, and the gener- Andrew W. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1970S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1970s Page 130 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1970 25 Or 6 To 4 Everything Is Beautiful Lady D’Arbanville Chicago Ray Stevens Cat Stevens Abraham, Martin And John Farewell Is A Lonely Sound Leavin’ On A Jet Plane Marvin Gaye Jimmy Ruffin Peter Paul & Mary Ain’t No Mountain Gimme Dat Ding Let It Be High Enough The Pipkins The Beatles Diana Ross Give Me Just A Let’s Work Together All I Have To Do Is Dream Little More Time Canned Heat Bobbie Gentry Chairmen Of The Board Lola & Glen Campbell Goodbye Sam Hello The Kinks All Kinds Of Everything Samantha Love Grows (Where Dana Cliff Richard My Rosemary Grows) All Right Now Groovin’ With Mr Bloe Edison Lighthouse Free Mr Bloe Love Is Life Back Home Honey Come Back Hot Chocolate England World Cup Squad Glen Campbell Love Like A Man Ball Of Confusion House Of The Rising Sun Ten Years After (That’s What The Frijid Pink Love Of The World Is Today) I Don’t Believe In If Anymore Common People The Temptations Roger Whittaker Nicky Thomas Band Of Gold I Hear You Knocking Make It With You Freda Payne Dave Edmunds Bread Big Yellow Taxi I Want You Back Mama Told Me Joni Mitchell The Jackson Five (Not To Come) Black Night Three Dog Night I’ll Say Forever My Love Deep Purple Jimmy Ruffin Me And My Life Bridge Over Troubled Water The Tremeloes In The Summertime Simon & Garfunkel Mungo Jerry Melting Pot Can’t Help Falling In Love Blue Mink Indian Reservation Andy Williams Don Fardon Montego Bay Close To You Bobby Bloom Instant Karma The Carpenters John Lennon & Yoko Ono With My -

Popular Music, Stars and Stardom

POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM EDITED BY STEPHEN LOY, JULIE RICKWOOD AND SAMANTHA BENNETT Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN (print): 9781760462123 ISBN (online): 9781760462130 WorldCat (print): 1039732304 WorldCat (online): 1039731982 DOI: 10.22459/PMSS.06.2018 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design by Fiona Edge and layout by ANU Press This edition © 2018 ANU Press All chapters in this collection have been subjected to a double-blind peer-review process, as well as further reviewing at manuscript stage. Contents Acknowledgements . vii Contributors . ix 1 . Popular Music, Stars and Stardom: Definitions, Discourses, Interpretations . 1 Stephen Loy, Julie Rickwood and Samantha Bennett 2 . Interstellar Songwriting: What Propels a Song Beyond Escape Velocity? . 21 Clive Harrison 3 . A Good Black Music Story? Black American Stars in Australian Musical Entertainment Before ‘Jazz’ . 37 John Whiteoak 4 . ‘You’re Messin’ Up My Mind’: Why Judy Jacques Avoided the Path of the Pop Diva . 55 Robin Ryan 5 . Wendy Saddington: Beyond an ‘Underground Icon’ . 73 Julie Rickwood 6 . Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers . 95 Vincent Perry 7 . When Divas and Rock Stars Collide: Interpreting Freddie Mercury and Montserrat Caballé’s Barcelona . -

May 1900) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 5-1-1900 Volume 18, Number 05 (May 1900) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 18, Number 05 (May 1900)." , (1900). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/448 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. — i/ObUIttE XVIII ^ /VlAy, 1900 SCHUBERT i^Uiwbe^ Editorials,.. i ■ 163 WITH SUPPLiEMEHT Questions and Answers,. 164 Home Notes, .164 d*44**44***44444*4****44*4***«*4*4t§**4<6«6**** A Studio Experience. W. J. Balt tell, ..164 4 Musical Items, ... '.J66 * New Publications, .167 * 4 The Greatest Difficulty for the Piano, 168 4 The Remoteness of Things. Titos. Tapper, ■ ■ . 169 4 A Scharwenka Anecdote, . 169 4 4 Thoughts, Suggestions, Advice, . 170 4 Five-minute Talk.' with Girls. Helena M. Maguire, 171 4 Haw to Handle S.ubfcorn Pupils. H. Patton,.171 4 Letters to Teachers. W. S. B. Matfuruis, 172 4 4 Too High \ims. E. -

Call on Khrushchev to Halt Laos Threat

Weatirar Distribution Today Cloudy with drinle today; 17,800 Ugh, 40>, Partly cloudy to- BEDBANK night and tomorrow. Low to- night, »». High tomorrow, S0>. 1 Independent Daily f See Weather page Z. (^ MONOAYTHKIVOHJlUDAY-lSrim J REGISTER SH 1-0010 iMUcd dtlly. Mondcy through FrlA*y. Second C1&H Poitsgt RED BANK, N. J., FRIDAY, MARCH 24, 1961 35c PER WEEK VOL. 83, NO. 187 Paid it Ked Bisk »nd at A&UUonil MUlln( OUlcei. 7c PER COPY BY CARRIER PAGE ONE Call on Khrushchev To Halt Laos Threat Macniillaii Off To America But U.S. LONDON (AP)-Prime Min- ister Harold Macmillan left by air today for a 19-day visit to Readies the United States, Canada and 1 the West Indies. He said he FOR RESEARCH INTO THE FUTURE — Aerial photo of th» Bell Labs Research Center, Holmdel Township, shows has "much to talk about" with building in its present-stage of construction — hearing completion. Structure in rear is 35,000-square-foot service President Kennedy. AidMove and maintenance building. Engineers say the center, to be ona of the largest research installations in the world, Aides laid that despite the urgency of the Laotian crisis, will be completed by October or November of this year and ready for occupancy early next year. WASHINGTON (AP) — Macmillan is adhering to his President Kepfiedy looked original schedule calling for a visit first to the West Indies hopefully to Soviet Premier Nearlng Completion in Holmdel «nd meetings with Kennedy Nikita Khrushchev today April 5-6. But the aides said if to call a halt to the Soviet- the situation in Laos got worse backed rebel offensive in of Premier Khrushchev reject- Bell Labs Center to Employ 2,500 ed the latest British-American Laos and avert mounting proposal of a cease-fire fol- danger of a U. -

Singles Chart-Chronology

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:13 Peak:1 Peak: 1 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Four Tops No. of Titles Positions The Four Tops are a vocal quartet from Detroit, Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 Michigan, USA, who helped to define the city's 13 7 -- -- 60 -- -- Motown sound of the 1960s. The group's 1 32 11 1 319 38 3 repertoire has included soul music, R&B, 1 45 7 2 382 38 4 disco, adult contemporary, doo-wop, jazz, and show tunes. 1 52 14 2 761 76 7 Founded as the Four Aims, lead singer Levi Stubbs, Abdul "Duke" Fakir, Renaldo "Obie" Benson and Lawrence Payton remained together for over four decades, performing from 1953 until 1997 without a change in personnel. ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 Baby I Need Your Loving 08/1964 11 12 2 Without The One You Love (Life's Not Worth While) 11/1964 43 5 3 Ask The Lonely 02/1965 24 8 4 I Can't Help Myself 07/1965 10 20 11005/1965 1 2 14 5 It's The Same Old Song 09/1965 34 8 07/1965 5 9 4 6 Ain't That Love 07/1965 93 1 7 Something About You 11/1965 19 7 8 Shake Me, Wake Me (When It's Over) 02/1966 18 9 9 Loving You Is Sweeter Than Ever 07/1966 21 12 05/1966 45 8 10 Reach Out, I'll Be There 12/1966 13 7 10/1966 1 3216 7709/1966 1 15 11 Standing In The Shadow Of Love 03/1967 29 2 01/1967 6 7 3512/1966 6 10 12 Bernadette 03/1967 8 17 2503/1967 4 10 13 7 Rooms Of Gloom 06/1967 12 9 05/1967 14 8 14 I'll Turn To Stone 07/1967 76 5 15 You Keep Running Away 10/1967 26 7 09/1967 19 -

The Social and Cultural Changes That Affected the Music of Motown Records from 1959-1972

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 2015 The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 Lindsey Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Baker, Lindsey, "The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972" (2015). Theses and Dissertations. 195. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/195 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. The Social and Cultural Changes that Affected the Music of Motown Records From 1959-1972 by Lindsey Baker A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements of the CSU Honors Program for Honors in the degree of Bachelor of Music in Performance Schwob School of Music Columbus State University Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Kevin Whalen Honors Committee Member ^ VM-AQ^A-- l(?Yy\JcuLuJ< Date 2,jbl\5 —x'Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz Dean of the Honors College ((3?7?fy/L-Asy/C/7^ ' Date Dr. Cindy Ticknor Motown Records produced many of the greatest musicians from the 1960s and 1970s. During this time, songs like "Dancing in the Street" and "What's Going On?" targeted social issues in America and created a voice for African-American people through their messages. Events like the Mississippi Freedom Summer and Bloody Thursday inspired the artists at Motown to create these songs. Influenced by the cultural and social circumstances of the Civil Rights Movement, the musical output of Motown Records between 1959 and 1972 evolved from a sole focus on entertainment in popular culture to a focus on motivating social change through music. -

Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown's Funk Brothers

6 Unsung Heroes: Recreating the Ensemble Dynamic of Motown’s Funk Brothers Vincent Perry Introduction By the early 1960s, the genre known as soul had become the most commercially successful of all the crossover styles. Drawing on musical influences from the genres of gospel, jazz and blues, ‘soul’s success was as much due to a number of labels, so-called “house sounds”, and little- known bands, as it was to specific performers or songwriters’ (Borthwick and Moy, 2004, p. 5). Following on from the pioneer releases of Ray Charles and Sam Cooke, a Detroit-based independent label would soon become the ‘most successful and high profile of all the soul labels’ (Borthwick and Moy, 2004, p. 5). Throughout the early 1960s, Berry Gordy’s Tamla Motown dominated the domestic US pop and R&B charts with its assembly-line approach to music production (Moorefield, 2005, p. 21), which resulted in a distinctive sound that was shared by all the label’s artists. However, in 1963, the company ‘achieved its international breakthrough’ shortly after signing a landmark distribution deal with EMI in the UK (Borthwick and Moy, 2004, p. 5). Gordy’s headquarters—a seemingly humble, suburban 95 POPULAR MUSIC, STARS AND STARDOM residence—was ambitiously named Hitsville USA and, throughout the 1960s, it became a hub for pop record success. Emerson (2005, p. 194) acknowledged Motown’s industry presence when he noted: Motown was muscling in on the market for dance music. Streamlined, turbo-charged singles by the Marvelettes, Martha and the Vandellas, and the Supremes rolled off the Detroit assembly line … Berry Gordy’s ‘Sound of Young America’ challenged the Brill Building, 1650 Broadway, and 711 Fifth Avenue as severely as the British Invasion because it proved that black artists did not need white writers to reach a broad pop audience. -

(1925-2014) Horn Arrangements for the Four Tops and the Temptations: a Lecture Recital

SMITH, RUSSELL ALAN, D.M.A. Gil Askey’s (1925-2014) Horn Arrangements for the Four Tops and the Temptations: A Lecture Recital. (2016) Directed by Prof. Timothy M. Clodfelter. 31 pp. 1. Solo Recital: Wednesday, April 23rd, 2014, 7:30 P.M., Recital Hall, UNCG. Caprice (Joseph Turrin); Sonata for Trumpet and Piano (Eric Ewazen); Concerto in C (Antonio Vivaldi); Quatre Variations sur un Theme de Domenico Scarlatti (Marcel Bitsch); All The Way (James Van Heusen) 2. Solo Recital: Sunday, February 15th, 2015, 5:30 P.M., Recital Hall, UNCG. Strap On Your Lobster (James Mobberley); Sonata for Trumpet and Piano (Kent Kennan); Fandango (Joseph Turrin); Songs of a Wayfarer (Gustav Mahler); Nocturno (Franz Strauss); The Preacher (Horace Silver) 3. Solo Recital: Wednesday, April 6th, 2016, 7:30 P.M., Organ Hall, UNCG. Postcards (Anthony Plog); Caprice (Eugen Bozza); Oblivion (Astor Piazzolla); The Rose Variations (Robert Russell Bennett); Concerto for Trumpet (Johann Neruda); Elegy (George Thalben-Ball) 4. D.M.A. Research Project. GIL ASKEY’S (1925-2014) HORN ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE FOUR TOPS AND THE TEMPTATIONS: A LECTURE RECITAL. This document accompanies a lecture recital that provided background biographical information and suggested techniques for performing the horn section arrangements of the Four Tops and the Temptations in a live setting. Introductory information about the scope and significance of the project and background biographical information about Motown Records Company and arranger Gil Askey were discussed. The logistical and performance challenges that must be addressed when executing these horn arrangements were explored as well. An examination of the melodic, harmonic and rhythmic elements contained in the horn section arrangements was presented along with stylistic performance considerations.