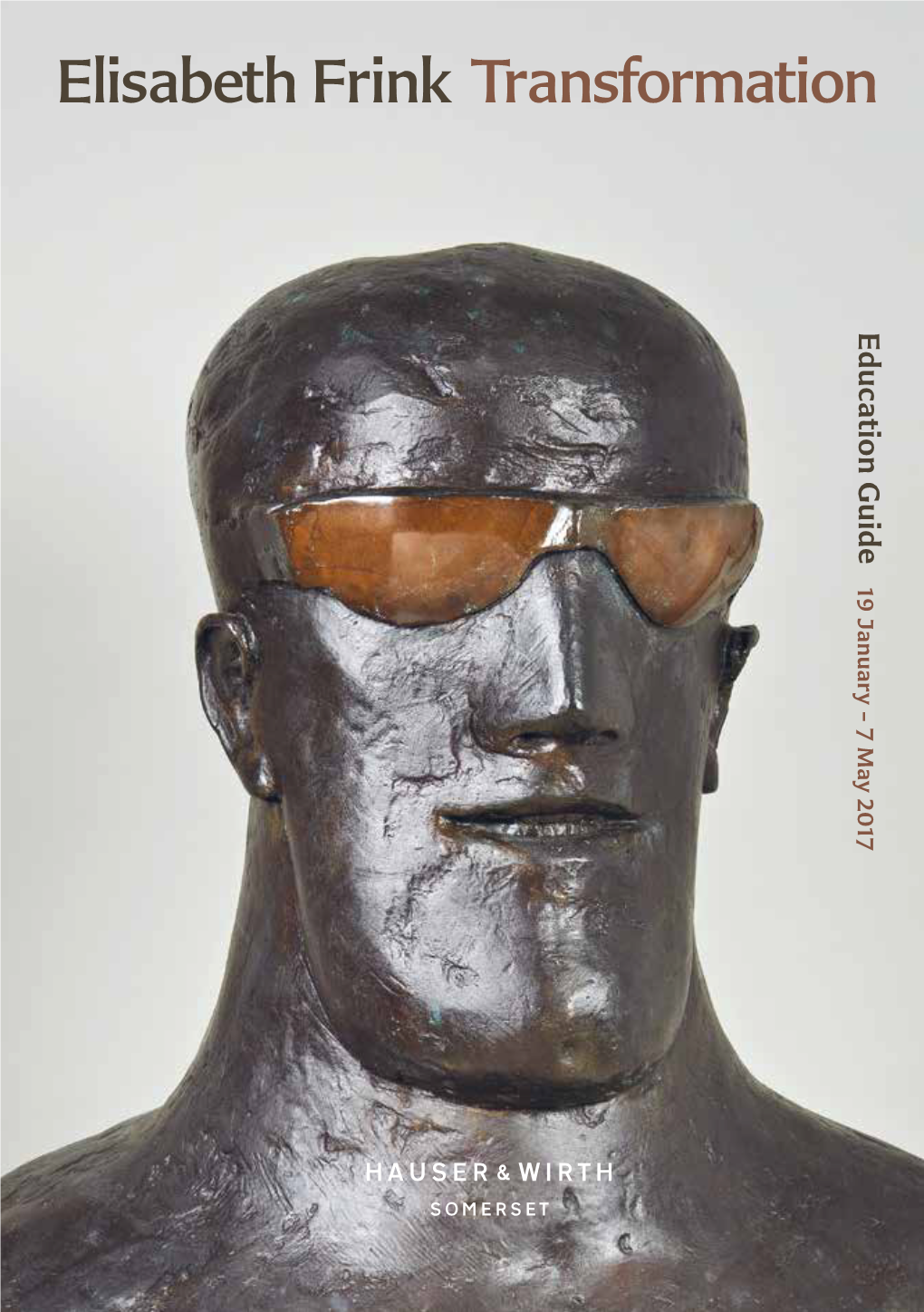

Elisabeth Frink Transformation Education Guide Education 19 January – 19 January 7 May 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Film Producer Buys Seacole Bust for 101 Times the Estimate

To print, your print settings should be ‘fit to page size’ or ‘fit to printable area’ or similar. Problems? See our guide: https://atg.news/2zaGmwp ISSUE 2454 | antiquestradegazette.com | 15 August 2020 | UK £4.99 | USA $7.95 | Europe €5.50 koopman rare art antiques trade KOOPMAN (see Client Templates for issue versions) THE ART M ARKET WEEKLY [email protected] +44 (0)20 7242 7624 www.koopman.art Face coverings Film producer buys Seacole now mandatory at auction rooms bust for 101 times the estimate across England A terracotta sculpture of Mary Seacole by Alex Capon (1805-81) sparked fierce competition at Dominic Winter. Wearing a face covering when Bidding at the South Cerney auction house attending an auction house in England began with 12 phones competing for the has now become mandatory. sculpture of Seacole, who nursed soldiers The updated guidance also applies to visitors to galleries and museums. during the Crimean War. Since July 24, face coverings have been It eventually came down to a final contest compulsory when on public transport as involving underbidder Art Aid and film well as in supermarkets and shops including producer Billy Peterson of Racing Green dealers’ premises and antique centres. The government announced that this Pictures, which is currently filming a would be extended in England from August biopic on Seacole’s life. 8 to include other indoor spaces such as Peterson will use the bust cinemas, theatres and places of worship. as a prop in the film. It will Auction houses also appear on this list. then be donated to the The measures, brought in by law, apply Mary Seacole Trust Continued on page 5 and be on view at the Florence Nightingale Museum. -

Germaine Richier, Cinq Oeuvres D'exception

« J’invente plus facilement en regardant la nature, sa présence me rend indépendante. » Germaine RICHIER morand & morand - germaine richier, cinq oeuvres d’exception - 3 novembre 2015 - paris drouot - 9 drouot 2015 - paris - 3 novembre d’exception - germaine richier, cinq oeuvres & morand morand germaine richier Cinq pièces d’exception germaine richier Cinq pièces d’exception Mardi 3 novembre 2015 à 17h - Drouot - salle 9 pré-exposition - salle 7 du 20 au 28 octobre expositions - salle 9 29 octobre – 11h - 21h 30 au 31 octobre – 11h - 18h 2 novembre – 11h - 18h 3 novembre – 11h - 15h conférences par Camille LEVEQUE-CLAUDET Commissaire de l’exposition Giacometti, Marini, Richier. La figure tourmentée, au Musée cantonal des Beaux-Arts de Lausanne. L’ œuvre de Germaine RICHIER - Jeudi 22 octobre - 19h30 - salle 3 Présentation des cinq œuvres de la vente - Samedi 24 octobre - 15h30 - salle 3 téléphone pendant l’exposition et la vente + 33 (0)1 48 00 20 09 expert de la vente Eric SCHOELLER +33 (0)6 11 86 39 64 / [email protected] responsable de la vente Cristina MOURAUT, commissaire-priseur +33 (0)1 40 56 91 96 / [email protected] Frais légaux : 12,66 % TTC TVA récupérable S.C.P. MORAND - 7, rue Ernest Renan 75015 Paris - Tél. 01 40 56 91 96- Fax. 01 47 34 74 85 Email : [email protected] - 10/01/02 - Internet : www.drouot-morand.com © Imagno - Franz Hubmann / LA COLLECTION Germaine Richier « Ma nature ne me permet pas le calme » Des êtres hybrides, mi-humain mi-animal, dont les membres, formes déchiquetées, arrachées à une matière bouillonnante, sont reliés par de fragiles fils métalliques. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Roland Piché ARCA FRBS Born 1938, London Art Education 1956-60 Hornsey College of Art Worked with sculptor Gaudia in Canada 1960-64 Royal College of Art 1963-64 Part-time assistant to Henry Moore Teaching Experience Slade School of Art Royal College of Art Central School of Art Falmouth School of Art Gloucestershire College of Art & Design Chelsea School of Art Birmingham Polytechnic Lancaster Polytechnic Manchester Polytechnic Goldsmiths College of Art Loughborough College of Art Newcastle upon Tyne Polytechnic Newport College of Art & Design North Staffordshire Polytechnic Stourbridge College of Art Trent Polytechnic West Surrey College of Art Wolverhampton Polytechnic Edinburgh School of Art Bristol Polytechnic (Sculpture) Leicester Polytechnic (Sculpture) 1964-89 Principal Lecturer, in charge of Sculpture, Maidstone College of Art Subject Leader, Sculpture, School of Fine Art, Kent Institute of Art & Design, Canterbury One Person Exhibitions 1967 Marlborough New London Gallery 1969 Gallery Ad Libitum, Antwerp B Middelheim Biennale, Antwerp B 1975 Canon Park, Birmingham 1980 The Ikon Gallery, Birmingham Minories Galleries, Colchester "Spaceframes & Circles" 1993 Kopp-Bardellini Agent Gallery, Zurich CH 2001 Glaxo Smith Kline - Harlow Research Centre 2005 Chappel Galleries, Essex 2010 Time & Life Building, London Group Exhibitions 1962 Towards Art I, Royal College of Art 1963-4 Young Contemporaries, AID Gallery 1964 Young Contemporary Artists, Whitechapel Gallery Maidstone College of Art Students, Show New Metropole Arts Centre, Folkestone 1965 Towards Art II, Royal College of Art, Sculpture at the Arts Council The New Generation, 1965, Whitechapel Gallery Whitworth Art Gallery Manchester Summer Exhibition Marlborough New London Gallery 4th Biennale de Paris 1966 The English Eye, Marlborough-Gerson Gallery, New York Structure 66, Arts Council of Gt. -

Out There: Our Post-War Public Art Elisabeth Frink, Boar, 1970, Harlow

CONTENTS 6 28—29 Foreword SOS – Save Our Sculpture 8—11 30—31 Brave Art For A Brave New World Out There Now 12—15 32—33 Harlow Sculpture Town Get Involved 16—17 34 Art For The People Acknowledgements 18—19 Private Public Art 20—21 City Sculpture Project All images and text are protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced 22—23 in any form or by any electronic means, without written permission of the publisher. © Historic England. Sculpitecture All images © Historic England except where stated. Inside covers: Nicholas Monro, King Kong for 24—27 the City Sculpture Project, 1972, the Bull Ring, Our Post-War Public Art Birmingham. © Arnolfini Archive 4 Out There: Our Post-War Public Art Elisabeth Frink, Boar, 1970, Harlow Out There: Our Post-War Public Art 5 FOREWORD Winston Churchill said: “We shape our buildings and afterwards our buildings shape us”. The generation that went to war against the Nazis lost a great many of their buildings – their homes and workplaces, as well as their monuments, sculptures and works of art. They had to rebuild and reshape their England. They did a remarkable job. They rebuilt ravaged cities and towns, and they built new institutions. From the National Health Service to the Arts Council, they wanted access-for-all to fundamental aspects of modern human life. And part of their vision was to create new public spaces that would raise the spirits. The wave of public art that emerged has shaped the England we live in, and it has shaped us. -

The Great Dorset Art Fair Dorset Art Weeks 2012 Kingston Mauward, Dorchester Open Studios • Exhibitions • Events 10Am - 4Pm 800 Artists at 300 Venues

[EVOLVER] Saturday 5 November 26 May - 10 June 2012 DORSET VISUAL ARTS presents DORSET VISUAL ARTS presents The Great Dorset Art Fair Dorset Art Weeks 2012 Kingston Mauward, Dorchester Open Studios • Exhibitions • Events 10am - 4pm 800 artists at 300 venues Entry: Dorset Art Weeks - DAW - is the biennial event run £5 • Kids Free • DVA Members £2.50 by Dorset Visual Arts. See: DAW is reputedly the country’s largest Open Studio Fine Arts, Video, Photography, Design, Ceramics, Event - with over 800 artists exhibiting work in over Furniture, Performative Arts and more by professional 300 venues. More than 120,000 studio visits were artists, designers and makers, arts organisations, registered in 2010 galleries, students and suppliers To enrich the event, demonstrations and cultural Revealed through: events will take place across Dorset. The Allsop Demonstrations, Displays and Stalls, Art Books and Gallery at Bridport Arts Centre will become a Materials. Live and Recorded Presentations working studio. You will, of course, know the event is Find out: upon us when you see the flowering of the red and Learn more about materials, processes and products. yellow banners and road signs. Interact with artists. Find out more about the rich One of the enduring appeals of Open Studios is the variety of visual arts that are taking place across quality of welcome visitors receive from artists. Of Dorset, including festivals, ambitious new projects and course they are interested in selling work - but they workshops are keen to share their ideas and techniques with Join in: local people and visitors to Dorset. • As an artist, designer or maker - via the Art Market As the event draws near, look out for our great • Place, taking a stall or applying to be in one of the brochure and postcards. -

Germaine Richier

GERMAINE RICHIER Born 1902 Grans, France Died 1959 Montpellier, France Education 1989 École des Beaux Arts, Montpellier Solo Exhibitions 2014 Germaine Richier, Dominique Lévy Gallery in collaboration with Galerie Perrotin, New York 2013 Germaine Richier: Rétrospective, Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern 2007 Germaine Richier, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice 1997 Germaine Richier, Akademie der Kunste, Berlin 1996 Germaine Richier: rétrospective, Fondation Maeght, Saint-Paul 1993 Olivier Debré. 50 tableaux pour un timbre. Découverte d'une autre édition artistique de la Poste: Germaine Richier, timbre Europa 1993, Musée de la Poste, Paris 1988 Germaine Richier, Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Copenhagen 1964 Germaine Richier, Musée Réattu, Arles 1963 Hommage a Germaine Richier, Musée Grimaldi-Chateau, Antibes Germaine Richier, Kunsthaus Zürich, Zürich 1959 Germaine Richier, Galerie Creuzevault, Paris Germaine Richier, Musée Grimaldi, Antibes Germaine Richier, Appel et Paolozzi, Martha Jackson Gallery, New York Sculpture by Germaine Richier, University School of Fine and Applied Arts, Boston 1958 Sculpture by Germaine Richier, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis Germaine Richier, Kunsthalle Bern, Bern 1957 Germaine Richier, Martha Jackson Gallery, New York 1956 Germaine Richier, Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris Germaine Richier, Galerie Berggruen, Paris 1955 Germaine Richier, Hanover Gallery, London Viera da Silva, Germaine Richier, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam 1954 Germaine Richier, Allan Frumkin Gallery, Chicago 1951 Die Plastiksammlung Werner Bar, Kunstmuseum, Winterthur 1948 Germaine Richier, Galerie Maeght, Paris 1947 Sculptures of Germaine Richier, engraving studio of Roger Lacourière, Anglo French Art Center, London 1946 Germaine Richier, Galerie Georges Moos, Geneva 1937 Méditerranée, Pavillon Languedoc Méditerranéen, Paris 1934 Solo exhibition, Galerie Max Kaganovitch, Paris Group Exhibitions 2014 Giacometti, Marini, Richier. -

The Smart Museum of Art BULLETIN 1998-1999

The Smart Museum of Art BULLETIN 1998-1999 CONTENTS Board and Committee Members 4 Report of the Chair and Director 5 Mission Statement 7 Volume 10, 1998-1999 Front cover: Three Kingdoms period, Silla King Studies in the Permanent Collection Copyright © 2000 by The David and Alfred Smart dom (57 B.c.E-935 C-E-) Pedestalledjar, 5th—6th Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 5550 century stoneware with impressed and combed Metaphors and Metaphorphosis: The Sculpture of Bernard Meadows South Greenwood Avenue, Chicago, Illinois, decoration and natural ash glaze deposits, h. 16 in the Early 1960s 9 60637. All rights reserved. inches (40.6 cm), Gift of Brooks McCormick Jr., RICHARD A. BORN 1999.13. ISSN: 1099-2413 Back cover: The Smart Museum's Vera and A.D. Black and White and Red All Over: Continuity and Transition in Elden Sculpture Garden, recently re-landscaped Editor: Stephanie P. Smith with a gift from Joel and Carole Bernstein. Robert Colescott's Paintings of the Late 1980s 17 Design: Joan Sommers Design STEPHANIE P. SMITH Printing: M&G Commercial Printing Photography credits: Pages 8-13, 16, 18, 24-40, Tom van Eynde. Page 20, Stephen Fleming. Pages Activities and Support 41 —43» 4 6> 48> 51. Lloyd de Grane. Pages 44, 45, 49, Rose Grayson. Page 5, Jim Newberry. Page 53, Acquisitions to the Permanent Collection 25 Jim Ziv. Front and back covers, Tom van Eynde. Loans from the Permanent Collection 36 The images on pages 18-22 are reproduced courtesy of Robert Colescott. The work by Imre Kinszki illustrated on page 24 and 31 is reproduced Exhibitions 39 courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York. -

Resource for Elisabeth Frink and Graham Sutherland, Willow Brook Primary School

Resource for Elisabeth Frink and Graham Sutherland, Willow Brook Primary School Dame Elisabeth Frink (1930–1993) Long-Eared Owl Lammergeier two prints from the Birds of Prey portfolio 1974 etching and aquatints Lammergeier shows a type of bearded vulture that lives in remote mountain areas across southern Europe, Africa and India, and is a species threatened with extinction. This huge bird has a wingspan of up to 3 metres. About the artist Dame Elisabeth Jean Frink (14 November 1930 – 18 April 1993) was an English sculptor and printmaker. She was born in Suffolk, and studied art in Guildford and London. While she was a student, the Tate Gallery bought one of her sculptures and this was the start of her successful career. Themes in her early drawings include wounded birds and falling men. Birds of prey were one of Elisabeth Frink’s favourite subjects in her art. As a child, living in the countryside, she remembered watching bomber planes flying overhead, while her father was abroad fighting in the Second World War. As an adult, she was interested in exploring different personalities of birds of prey. Their fierceness reminded her of how scared she had felt as a child. She was part of a postwar group of British sculptors, dubbed the Geometry of Fear school, that included Reg Butler, Bernard Meadows, Kenneth Armitage and Eduardo Paolozzi. Frink’s subject matter included men, birds, dogs, horses and religious motifs, but very seldom any female forms. She lived for a time in the mountains of the south of France, before returning to live in Dorset. -

Lynn Chadwick out of the Shadows Unseen Sculpture of the 1960S

LYNN CHADWICK OUT OF THE SHADOWS UNSEEN SCULPTURE OF THE 1960S 1 INTRODUCTION ince my childhood in Africa I have been fascinated and stimulated by Lynn SChadwick’s work. I was drawn both by the imagery and the tangible making process which for the first time enabled my child’s mind to respond to and connect with modern sculpture in a spontaneous way. I was moved by the strange animalistic figures and intrigued by the lines fanning across their surfaces. I could see that the lines were structural but also loved the way they appeared to energise the forms they described. I remember scrutinising photographs of Lynn’s sculptures in books and catalogues. Sometimes the same piece appeared in two books but illustrated from different angles which gave me a better understanding of how it was constructed. The connection in my mind was simple. I loved skeletons and bones of all kinds and morbidly collected dead animals that had dried out in the sun, the skin shrinking tightly over the bones beneath. These mummified remains were somehow more redolent of their struggle for life than if they were alive, furred and feathered and to me, Lynn’s sculpture was animated by an equal vivacity. His structures seemed a natural and logical way to make an object. Around me I could see other structures that had a similar economy of means; my grandmother’s wire egg basket, the tissue paper and bamboo kites I built and the pole and mud constructions of the African houses and granaries. This fascination gave me a deep empathy with Lynn’s working method and may eventually have contributed to the success of my relationship with him, casting his work for over twenty years. -

'Reforming Academicians', Sculptors of the Royal Academy of Arts, C

‘Reforming Academicians’, Sculptors of the Royal Academy of Arts, c.1948-1959 by Melanie Veasey Doctoral Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University, September 2018. © Melanie Veasey 2018. For Martin The virtue of the Royal Academy today is that it is a body of men freer than many from the insidious pressures of fashion, who stand somewhat apart from the new and already too powerful ‘establishment’.1 John Rothenstein (1966) 1 Rothenstein, John. Brave Day Hideous Night. London: Hamish Hamilton Ltd., 1966, 216. Abstract Page 7 Abstract Post-war sculpture created by members of the Royal Academy of Arts was seemingly marginalised by Keynesian state patronage which privileged a new generation of avant-garde sculptors. This thesis considers whether selected Academicians (Siegfried Charoux, Frank Dobson, Maurice Lambert, Alfred Machin, John Skeaping and Charles Wheeler) variously engaged with pedagogy, community, exhibition practice and sculpture for the state, to access ascendant state patronage. Chapter One, ‘The Post-war Expansion of State Patronage’, investigates the existing and shifting parameters of patronage of the visual arts and specifically analyses how this was manifest through innovative temporary sculpture exhibitions. Chapter Two, ‘The Royal Academy Sculpture School’, examines the reasons why the Academicians maintained a conventional fine arts programme of study, in contrast to that of industrial design imposed by Government upon state art institutions for reasons of economic contribution. This chapter also analyses the role of the art-Master including the influence of émigré teachers, prospects for women sculpture students and the post-war scarcity of resources which inspired the use of new materials and techniques. -

ROBERT ADAMS (British, 1917-1984)

ROBERT ADAMS (British, 1917-1984) “I am concerned with energy, a physical property inherent in metal, [and] in contrasts between linear forces and masses, between solid and open areas … the aim is stability and movement in one form.” (R. Adams, 1966, quoted in A. Grieve, 1992, pp. 109-111) Robert Adams was born in Northampton, England, in October 1917. He has been called “the neglected genius of post-war British sculpture” by critics. In 1937, Adams began attending evening classes in life drawing and painting at the Northampton School of Art. Some of Adam’s first-ever sculptures were also exhibited in London between 1942 and 1944 as part of a series of art shows for artists working in the Civil Defence, which Adams joined during the Second World War. He followed this with his first one-man exhibition at Gimpel Fils Gallery, London, in 1947, before starting a 10-year teaching career in 1949 at the Central School of Art and Design in London. It was during this time that Adams connected with a group of abstract painters – importantly Victor Pasmore, Adrian Heath and Kenneth and Mary Martin – finding a mutual interest in Constructivist aesthetics and in capturing movement. In 1948, Adams’ stylistic move towards abstraction was further developed when he visited Paris and seeing the sculpture of Pablo Picasso, Julio Gonzales, Constantine Brancusi and Henry Laurens. As such, Adams’ affiliation with his fellow English carvers, such as Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth, extended only as far as an initial desire to carve in stone and wood. Unlike his contemporaries, Adams did not appear to show much interest in the exploration of the human form or its relationship to the landscape.