Anglican and Episcopal History Editor-In-Chief Edward L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open / Summer 2001

journal of the associated parishes OPEN for liturgy and mission Summer 2001 Vol. 47 No. 2 Santa Fé Statement of the Council of Associated Parishes he Council of the Associated Parishes for Liturgy and Mission, meeting in Santa Fé, New Mexico, in April 2001, calls upon the Inside TChurch to rethink completely its practice and understanding of mission. This issue deals entirely with Our hearts burned within us as our Canadian members shared the reconsidering the mission of the church. See also . story of how the Anglican Church of Canada embraced and implement- ed the government’s policy of assimilation of indigenous peoples as an Associated Parishes opportunity to further its mission. Children were taken out of their asks complete rethinking of homes and removed to distant residential schools, run by the churches. mission .................................2 Grave injustices were committed by the Anglican and other churches, Doug Tindal: Where we have with dire consequences to the peoples and ultimately to the churches been .....................................4 themselves. As a Council dedicated to the renewal of liturgy and mission, we Gordon Beardy: My hope is asked ourselves how the Church could have come to be an agent of the that we will journey together .6 kind of “mission” revealed in this story. It prompts us to acknowledge The system was wrong .........8 our own inherent racism, past collusion, and present complicity in such policies. Evangelism predicated upon the conversion of individual Catherine Morrison: Steps on a hearts to a relationship with Jesus is insufficient to prevent such evils healing path ..........................9 as the deprivation of culture, and may serve as little more than a means for achieving assimilation. -

Bristol Open Doors Day Guide 2017

BRING ON BRISTOL’S BIGGEST BOLDEST FREE FESTIVAL EXPLORE THE CITY 7-10 SEPTEMBER 2017 WWW.BRISTOLDOORSOPENDAY.ORG.UK PRODUCED BY WELCOME PLANNING YOUR VISIT Welcome to Bristol’s annual celebration of This year our expanded festival takes place over four days, across all areas of the city. architecture, history and culture. Explore fascinating Not everything is available every day but there are a wide variety of venues and activities buildings, join guided tours, listen to inspiring talks, to choose from, whether you want to spend a morning browsing or plan a weekend and enjoy a range of creative events and activities, expedition. Please take some time to read the brochure, note the various opening times, completely free of charge. review any safety restrictions, and check which venues require pre-booking. Bristol Doors Open Days is supported by Historic England and National Lottery players through the BOOKING TICKETS Heritage Lottery Fund. It is presented in association Many of our venues are available to drop in, but for some you will need to book in advance. with Heritage Open Days, England’s largest heritage To book free tickets for venues that require pre-booking please go to our website. We are festival, which attracts over 3 million visitors unable to take bookings by telephone or email. Help with accessing the internet is available nationwide. Since 2014 Bristol Doors Open Days has from your local library, Tourist Information Centre or the Architecture Centre during gallery been co-ordinated by the Architecture Centre, an opening hours. independent charitable organisation that inspires, Ticket link: www.bristoldoorsopenday.org.uk informs and involves people in shaping better buildings and places. -

Westminster Abbey a Service for the New Parliament

St Margaret’s Church Westminster Abbey A Service for the New Parliament Wednesday 8th January 2020 9.30 am The whole of the church is served by a hearing loop. Users should turn the hearing aid to the setting marked T. Members of the congregation are kindly requested to refrain from using private cameras, video, or sound recording equipment. Please ensure that mobile telephones and other electronic devices are switched off. The service is conducted by The Very Reverend Dr David Hoyle, Dean of Westminster. The service is sung by the Choir of St Margaret’s Church, conducted by Greg Morris, Director of Music. The organ is played by Matthew Jorysz, Assistant Organist, Westminster Abbey. The organist plays: Meditation on Brother James’s Air Harold Darke (1888–1976) Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’ BWV 678 Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) The Lord Speaker is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. The Speaker of the House of Commons is received at the East Door. All stand as he is conducted to his seat, and then sit. 2 O R D E R O F S E R V I C E All stand to sing THE HYMN E thou my vision, O Lord of my heart, B be all else but naught to me, save that thou art, be thou my best thought in the day and the night, both waking and sleeping, thy presence my light. Be thou my wisdom, be thou my true word, be thou ever with me, and I with thee, Lord; be thou my great Father, and I thy true son, be thou in me dwelling, and I with thee one. -

Records of Bristol Cathedral

BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY’S PUBLICATIONS General Editors: MADGE DRESSER PETER FLEMING ROGER LEECH VOL. 59 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 RECORDS OF BRISTOL CATHEDRAL EDITED BY JOSEPH BETTEY Published by BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 2007 1 ISBN 978 0 901538 29 1 2 © Copyright Joseph Bettey 3 4 No part of this volume may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, 5 electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information 6 storage or retrieval system. 7 8 The Bristol Record Society acknowledges with thanks the continued support of Bristol 9 City Council, the University of the West of England, the University of Bristol, the Bristol 10 Record Office, the Bristol and West Building Society and the Society of Merchant 11 Venturers. 12 13 BRISTOL RECORD SOCIETY 14 President: The Lord Mayor of Bristol 15 General Editors: Madge Dresser, M.Sc., P.G.Dip RFT, FRHS 16 Peter Fleming, Ph.D. 17 Roger Leech, M.A., Ph.D., FSA, MIFA 18 Secretaries: Madge Dresser and Peter Fleming 19 Treasurer: Mr William Evans 20 21 The Society exists to encourage the preservation, study and publication of documents 22 relating to the history of Bristol, and since its foundation in 1929 has published fifty-nine 23 major volumes of historic documents concerning the city. -

Uniform Dress and Appearance Regulations for the Royal Air Force Air Cadets (Ap1358c)

UNIFORM DRESS AND APPEARANCE REGULATIONS FOR THE ROYAL AIR FORCE AIR CADETS (AP1358C) HQAC (ATF) – DEC 2018 by authority of HQ Air Command reviewed by HQAC INTENTIONALLY BLANK 2 Version 3.0 AMENDMENT LIST RECORD Amended – Red Text Pending – Blue Text AMENDMENT LIST AMENDED BY DATE AMENDED NO DATE ISSUED Version 1.01 14 Aug 12 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 06 Aug 12 Version 1.02 22 Apr 13 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 15 Mar 13 Version 1.03 11 Nov 13 WO Mitchell ATF HQAC 07 Nov 13 Version 1.04 05 Dec 13 FS Moss ATF HQAC 04 Dec 13 Version 1.05 19 Jun 14 FS Moss ATF HQAC 19 Jun 14 Version 1.06 03 Jul 14 FS Moss ATF HQAC 03 Jul 14 Version 1.07 19 Mar 15 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO(ATC) Mundy RWO L&SE 19 Mar 15 Version 2.00 05 Feb 17 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO(ATC) Mundy RWO L&SE 05 Feb 17 Version 3.00 04 Dec 18 WO Mannion ATF HQAC / WO Mundy RAFAC RWO L&SE 04 Dec 18 3 Version 3.0 NOTES FOR USERS 1. This manual supersedes ACP 20B Dress Regulations. All policy letters or internal briefing notices issued up to and including December 2018 have been incorporated or are obsoleted by this version. 2. Further changes to the Royal Air Force Air Cadets Dress Orders will be notified by amendments issued bi-annually or earlier if required. 3. The wearing of military uniform by unauthorised persons is an indictable offence under the Uniforms Act 1894. -

Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments

Fordham Law Review Volume 66 Issue 4 Article 35 1998 Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments Samuel J. Levine Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Samuel J. Levine, Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments, 66 Fordham L. Rev. 1505 (1998). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol66/iss4/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Religious Symbols and Religious Garb in the Courtroom: Personal Values and Public Judgments Cover Page Footnote Assistant Legal Writing Professor & Lecturer in Jewish Law, St. John's University School of Law; B.A. 1990, Yeshiva University; J.D. 1994, Fordham University; Ordination 1996, Yeshiva University; LL.M. 1996, Columbia University. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol66/iss4/35 RELIGIOUS SYMBOLS AND RELIGIOUS GARB IN THE COURTROOM: PERSONAL VALUES AND PUBLIC JUDGMENTS Samuel J. Levine* INTRODUCTION A S a nation that values and guarantees religious freedom, the fUnited States is often faced with questions regarding the public display of religious symbols. Such questions have arisen in a number of Supreme Court cases, involving both Establishment Clause and Free Exercise Clause issues. -

Archbishop Peers Brings Greetings From

Page 4 Friday, July 6, 2001 Standing ovation Archbishop Peers brings greetings from ACC rchbishop Michael of urgency he’s brought to the Peers of the Anglican discussions.” Such simple ges- AChurch of Canada was tures as attending each other’s introduced by Rev Jon worship services and partici- Fogleman, and welcomed with pating in each other’s meet- a standing round of applause. ings reflects us back to our- He began his remarks by selves and is an enormous stating it was a pleasure to be help. This has been part of our with us, but that he missed way of discerning things, of being present for the whole doing things.” convention, as has been his He also brought greetings custom in the past. Both from the General Synod of the churches have made accom- ACC which began last night. modations for this meeting, He indicated that he is looking both in location and time. Our forward to the Lutheran World efforts together have been part Federation gathering in 2003, of a worldwide movement having had a hand in the suc- between Anglicans and cessful campaign to bring it to Lutherans, but we here in Canada. He hopes the ACC Canada are different from can be of assistance with this other countries and do things and to share in the event. our own way, he said. Archbishop Peers closed by “The great thing we’ve saying he was grateful to God managed to do is to meet each for the privilege of being able other, to get to know each to share.. -

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Colston, Edward (1636–1721) Kenneth Morgan

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Colston, Edward (1636–1721) Kenneth Morgan • Published in print: 23 September 2004 • Published online: 23 September 2004 • This version: 9th July 2020 Colston, Edward (1636–1721), merchant, slave trader, and philanthropist, was born on 2 November 1636 in Temple Street, Bristol, the eldest of probably eleven children (six boys and five girls are known) of William Colston (1608–1681), a merchant, and his wife, Sarah, née Batten (d. 1701). His father had served an apprenticeship with Richard Aldworth, one of the wealthiest Bristol merchants of the early Stuart period, and had prospered as a merchant. A royalist and an alderman, William Colston was removed from his office by order of parliament in 1645 after Prince Rupert surrendered the city to the roundhead forces. Until that point Edward Colston had been brought up in Bristol and probably at Winterbourne, south Gloucestershire, where his father had an estate. The Colston family moved to London during the English civil war. Little is known about Edward Colston's education, though it is possible that he was a private pupil at Christ's Hospital. In 1654 he was apprenticed to the London Mercers' Company for eight years. By 1672 he was shipping goods from London, and the following year he was enrolled in the Mercers' Company. He soon built up a lucrative mercantile business, trading with Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Africa. From the 1670s several of Colston’s immediate family members became involved in the Royal African Company, and Edward became a member himself on 26 March 1680. The Royal African Company was a chartered joint-stock Company based in London. -

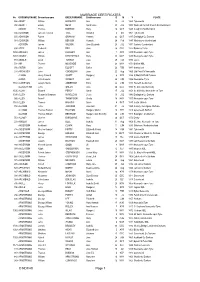

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES © NDFHS Page 1

MARRIAGE CERTIFICATES No GROOMSURNAME Groomforename BRIDESURNAME Brideforename D M Y PLACE 588 ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul 1869 Tynemouth 935 ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 JUL 1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16 OCT 1849 Coughton Northampton 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth 655 ADAMSON Robert GRAHAM Hannah 23 OCT 1847 Darlington Co Durham 581 ADAMSON William BENSON Hannah 24 Feb 1847 Whitehaven Cumberland ADDISON James WILSON Jane Elizabeth 23 JUL 1871 Carlisle, Cumberland 694 ADDY Frederick BELL Jane 26 DEC 1922 Barnsley Yorks 1456 AFFLECK James LUCKLEY Ann 1 APR 1839 Newcastle upon Tyne 1457 AGNEW William KIRKPATRICK Mary 30 MAY 1887 Newcastle upon Tyne 751 AINGER David TURNER Eliza 28 FEB 1870 Essex 704 AIR Thomas MCKENZIE Ann 24 MAY 1871 Belford NBL 936 AISTON John ELLIOTT Esther 26 FEB 1881 Sunderland 244 AITCHISON John COCKBURN Jane 22 Aug 1865 Utd Pres Ch Newcastle ALBION Henry Edward SCOTT Margaret 6 APR 1884 St Mark Millfield Durham ALDER John Cowens WRIGHT Ann 24 JUN 1856 Newcastle /Tyne 1160 ALDERSON Joseph Henry ANDERSON Eliza 22 JUN 1897 Heworth Co Durham ALLABURTON John GREEN Jane 24 DEC 1842 St. Giles ,Durham City 1505 ALLAN Edward PERCY Sarah 17 JUL 1854 St. Nicholas, Newcastle on Tyne 1390 ALLEN Alexander Bowman WANDLESS Jessie 10 JUL 1943 Darlington Co Durham 992 ALLEN Peter F THOMPSON Sheila 18 MAY 1957 Newcastle upon Tyne 1161 ALLEN Thomas HIGGINS Annie 4 OCT 1887 South Shields 158 ALLISON John JACKSON Jane Ann 31 Jul 1859 Colliery, Catchgate, -

Glory Laud & Honour

A section of the Anglican Journal MAY 2018 IN THIS ISSUE Stewardship Day Telling God’s Story in Your Parish PAGES 10 – 11 Learning Party Long Long with Night of Hope Emily Scott — Year 2 PAGES 12 & 13 PAGE 9 All Glory Laud & Honour LEFT Bishop Skelton and Rev. Allan Carson prepare to take their places for the Liturgy of the Palms. RIGHT Bishop Skelton leads the Liturgy of the Palms while folks of all ages participate. As part of her 2018 episcopal visitation schedule, Bishop on March 25, 2018. It was a beautiful morning in that Melissa Skelton travelled to her parish of St. John the southeastern Fraser Valley town and the early 20th century Baptist, Sardis to join the rector, the Rev. Allan Carson and wooden church was filled to capacity. Worship began with the St. John’s community for the Palm Sunday Eucharist CONTINUED ON PAGE 2 Acolyte, Ethan waits for the procession to form behind him. Bishop Skelton speaks to the younger members of the parish about the meaning of Palm Sunday. For more Diocesan news and events visit www.vancouver.anglican.ca 2 MAY 2018 Special Synod All Glory Laud & Honour this Coming October 2018 STEPHEN MUIR, (WITH NOTES FROM GEORGE CADMAN, QC, ODNW, CHANCELLOR OF THE DIOCESE) Archdeacon of Capilano, Rector of St. Agnes, Co-chair of the Canon 2 Task Force Bishop Skelton has advised Diocesan Council, the elected and appointed governing body of the diocese that she intends to convene a Special Synod on October 13, 2018. The purpose of the Synod will be to consider changes to Canon 2, the set of rules, which govern how a bishop is elected in the diocese of New Westminster. -

The Dorcan Church

Anglican: Methodist: Diocese of Bristol Bristol District, Swindon and Marlborough Circuit _____________________________________________________________________________________ The Dorcan Church _____________________________________________________________________________________ The Dorcan Church 5-06-2013 v2 1 http://www.dorcanchurch.co.uk/ Anglican: Methodist: Diocese of Bristol Bristol District, Swindon and Marlborough Circuit _____________________________________________________________________________________ Our Mission Statement God calls us as a Church to live and share the Good News of God’s Love so that all people have the opportunity to become followers of Jesus Christ. Relying on the Holy Spirit’s Power, we commit ourselves to being open to change to make mission our top priority by: Building bridges within our local communities Offering worship that is welcoming, understandable and centered in the presence of God Building relationships where all are cared for and can grow in wholeness Making opportunities to pray regularly and together Helping people understand the Christian faith and live it Actively supporting the values of God’s kingdom: justice, reconciliation and care for people in need Who we are and what we are doing The Dorcan Church is a local Ecumenical Partnership between the Church of England and the Methodist Church serving the Swindon urban villages of Covingham, Nythe, Liden and Eldene. The partnership includes the congregation of St Paul’s Church Centre, Covingham, St Timothy’s Church, Liden and Eldene Community Centre. We are a mix of friendly, lively, all age people, that present as a ‘bag of surprises’, but needing more 20s and 30s. We need you to join with our Methodist Minister and Ministry Team to help us grow in number and engage with our local community in new ways. -

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society Unwanted

Northumberland and Durham Family History Society baptism birth marriage No Gsurname Gforename Bsurname Bforename dayMonth year place death No Bsurname Bforename Gsurname Gforename dayMonth year place all No surname forename dayMonth year place Marriage 933ABBOT Mary ROBINSON James 18Oct1851 Windermere Westmorland Marriage 588ABBOT William HADAWAY Ann 25 Jul1869 Tynemouth Marriage 935ABBOTT Edwin NESS Sarah Jane 20 Jul1882 Wallsend Parrish Church Northumbrland Marriage1561ABBS Maria FORDER James 21May1861 Brooke, Norfolk Marriage 1442 ABELL Thirza GUTTERIDGE Amos 3 Aug 1874 Eston Yorks Death 229 ADAM Ellen 9 Feb 1967 Newcastle upon Tyne Death 406 ADAMS Matilda 11 Oct 1931 Lanchester Co Durham Marriage 2326ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth SOMERSET Ernest Edward 26 Dec 1901 Heaton, Newcastle upon Tyne Marriage1768ADAMS Thomas BORTON Mary 16Oct1849 Coughton Northampton Death 1556 ADAMS Thomas 15 Jan 1908 Brackley, Norhants,Oxford Bucks Birth 3605 ADAMS Sarah Elizabeth 18 May 1876 Stockton Co Durham Marriage 568 ADAMSON Annabell HADAWAY Thomas William 30 Sep 1885 Tynemouth Death 1999 ADAMSON Bryan 13 Aug 1972 Newcastle upon Tyne Birth 835 ADAMSON Constance 18 Oct 1850 Tynemouth Birth 3289ADAMSON Emma Jane 19Jun 1867Hamsterley Co Durham Marriage 556 ADAMSON James Frederick TATE Annabell 6 Oct 1861 Tynemouth Marriage1292ADAMSON Jane HARTBURN John 2Sep1839 Stockton & Sedgefield Co Durham Birth 3654 ADAMSON Julie Kristina 16 Dec 1971 Tynemouth, Northumberland Marriage 2357ADAMSON June PORTER William Sidney 1May 1980 North Tyneside East Death 747 ADAMSON