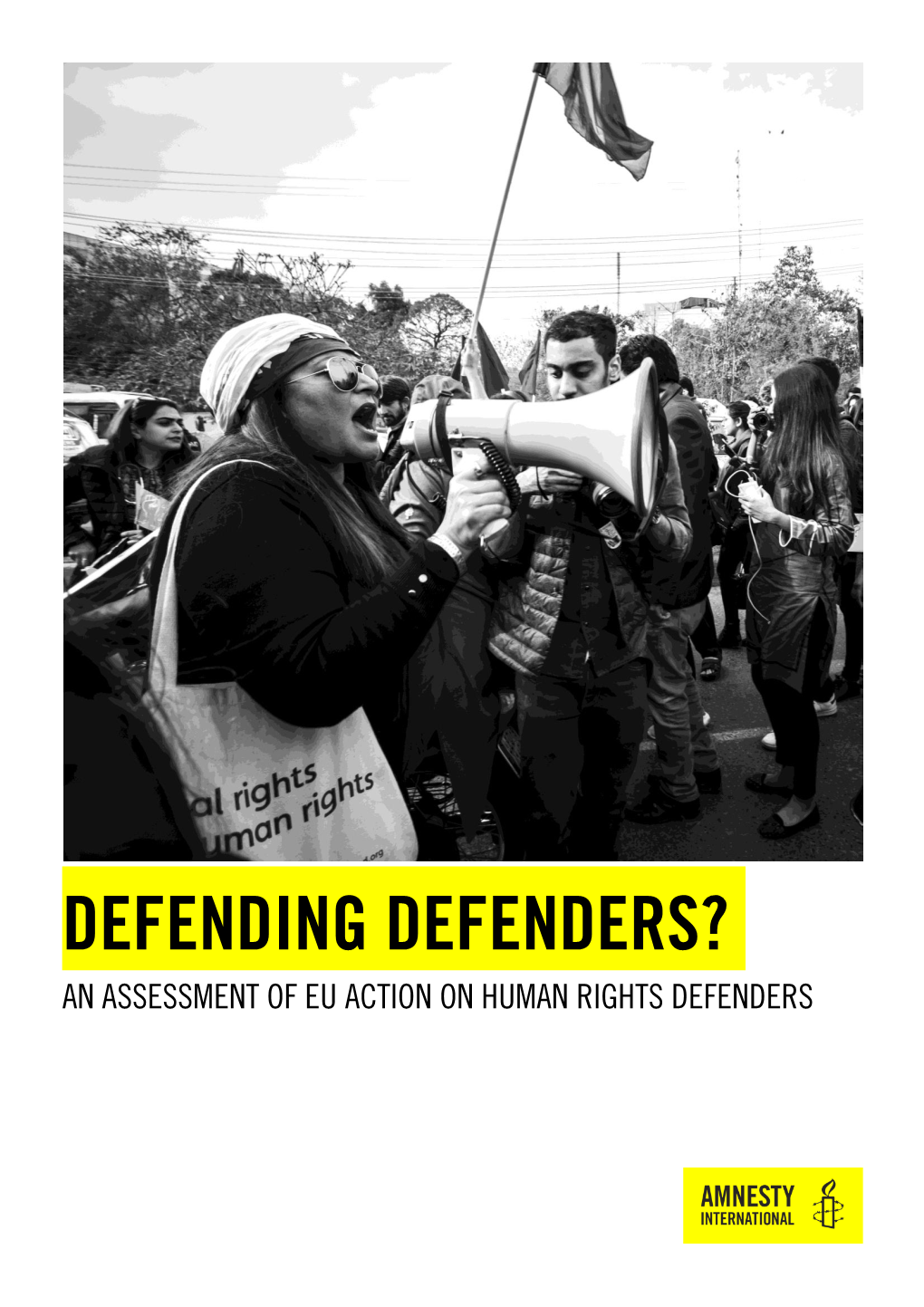

Defending Defenders? an Assessment of Eu Action on Human Rights Defenders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SUSTAINABILITY CIES 2019 San Francisco • April 14-18, 2019 ANNUAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM RD 6 3

EDUCATION FOR SUSTAINABILITY CIES 2019 San Francisco • April 14-18, 2019 ANNUAL CONFERENCE PROGRAM RD 6 3 #CIES2019 | #Ed4Sustainability www.cies.us SUN MON TUE WED THU 14 15 16 17 18 GMT-08 8 AM Session 1 Session 5 Session 10 Session 15 8 - 9:30am 8 - 9:30am 8 - 9:30am 8 - 9:30am 9 AM Coffee Break, 9:30am Coffee Break, 9:30am Coffee Break, 9:30am Coffee Break, 9:30am 10 AM Pre-conference Workshops 1 Session 2 Session 6 Session 11 Session 16 10am - 1pm 10 - 11:30am 10 - 11:30am 10 - 11:30am 10 - 11:30am 11 AM 12 AM Plenary Session 1 Plenary Session 2 Plenary Session 3 (includes Session 17 11:45am - 1:15pm 11:45am - 1:15pm 2019 Honorary Fellows Panel) 11:45am - 1:15pm 11:45am - 1:15pm 1 PM 2 PM Session 3 Session 7 Session 12 Session 18 Pre-conference Workshops 2 1:30 - 3pm 1:30 - 3pm 1:30 - 3pm 1:30 - 3pm 1:45 - 4:45pm 3 PM Session 4 Session 8 Session 13 Session 19 4 PM 3:15 - 4:45pm 3:15 - 4:45pm 3:15 - 4:45pm 3:15 - 4:45pm Reception @ Herbst Theatre 5 PM (ticketed event) Welcome, 5pm Session 9 Session 14 Closing 4:30 - 6:30pm 5 - 6:30pm 5 - 6:30pm 5 - 6:30pm Town Hall: Debate 6 PM 5:30 - 7pm Keynote Lecture @ Herbst 7 PM Theatre (ticketed event) Presidential Address State of the Society Opening Reception 6:30 - 9pm 6:45 - 7:45pm 6:45 - 7:45pm 7 - 9pm 8 PM Awards Ceremony Chairs Appreciation (invite only) 7:45 - 8:30pm 7:45 - 8:45pm 9 PM Institutional Receptions Institutional Receptions 8:30 - 9:45pm 8:30 - 9:45pm TABLE of CONTENTS CIES 2019 INTRODUCTION OF SPECIAL INTEREST Conference Theme . -

EP SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER May 2014

EP SAKHAROV PRIZE NETWORK NEWSLETTER May 2014 EUROPEAN YOUTH EVENT (EYE) ATTENDED BY SAKHAROV LAUREATES Olivier Basille, representing 2005 Sakharov Prize Laureate Reporters Without Borders, and Kirill Koroteev representing Memorial, the 2009 Laureate, took part in the EYE in Strasbourg from 9-11 May. The event brought together 5,000 Europeans aged 16-30. Basille urged Europe's youth to get involved in the promotion of human rights saying that "courage has to be learnt; people should not be afraid to adopt non-anonymity when tackling issues that require courage"; he also highlighted the importance of social media for democracy, and the need to fight restrictive media laws. Koroteev suggested that young people use social media to spread the word about rights contraventions, and that the EU not condone violations: "those who do not take measures against those who do not respect human rights are considered supporters of the wrongdoings of non-democratic regimes". Memorial to register as a foreign agent; criticises the Justice Ministry's proposal to close NGOs extra-judicially and expresses concerns about the possibility of turning off social media 23-03-2014: A District Court of Moscow confirmed the Prosecutor's order that Memorial Human Rights Centre, the 2009 Sakharov Laureate, is obliged to register as a "foreign agent". The decision came on the same day as the adoption by the Russian Duma of provisions that will allow the Ministry of Justice to register NGOs as “foreign agents” at its own initiative, without a court decision. 2009 Sakharov Prize Laureates Lyudmila Alexeyeva and Memorial have spoken out against the proposal. -

Status Report 2019 Table of Contents Status Report 2019

A HIGH PRICE Status Report 2019 Table of Contents Status Report 2019 Table of Contents Introduction 3. Azerbaijan 4. Burma 5. Cuba 6. Ethiopia 7. Turkey 8. 2. Introduction Status Report 2019 A High Price for Important Journalism Across the globe, an increasing number of states are cracking down on freedom of expression. In many places, it is virtually non-existent. Writing, speaking or in any way expressing opposing views on a given topic entails enormous risks. Threats, persecution, arrest, imprisonment and torture are only a few of the horrors facing those who speak out. This status report addresses the situation in five countries in which freedom of expression is limited. In it, journalists and human rights defenders will testify to how severe the consequences are. What unites them is the high price they have had to pay for doing their job. Not only have they been arrested, imprisoned and threatened with their life; they have been rejected by their friends and families, slandered and harassed. The consequences of their work and dedication have severely impacted their social lives. Living in constant fear has pushed journalists and opinion makers toward self-censorship. The silencing of these voices is harmful to a democratic society. We must work together to change this. Anders L Pettersson Executive Director Civil Rights Defenders 3. Azerbaijan Status Report 2019 More Dangerous Than Ever To openly report about the situation in Azerbaijan has never been as dangerous as it is right now. The government’s control over the media and civil society has increased. As a result, the situation for journalists is becoming more and more dangerous and vulnerable. -

Daring to Stand up for Human Rights in a Pandemic

DARING TO STAND UP FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN A PANDEMIC Artwork by Jaskiran K Marway @J.Kiran90 INDEX: ACT 30/2765/2020 AUGUST 2020 LANGUAGE: ENGLISH amnesty.org 1 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 1. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF DEFENDING HUMAN RIGHTS DURING A PANDEMIC 5 2. ATTACKS DURING THE COVID-19 CRISIS 7 2.1 COVID-19, A PRETEXT TO FURTHER ATTACK DEFENDERS AND REDUCE CIVIC SPACE 8 2.2 THE DANGERS OF SPEAKING OUT ON THE RESPONSE TO THE PANDEMIC 10 2.3 DEFENDERS EXCLUDED FROM RELEASE DESPITE COVID-19 – AN ADDED PUNISHMENT 14 2.4 DEFENDERS AT RISK LEFT EXPOSED AND UNPROTECTED 16 2.5 SPECIFIC RISKS ASSOCIATED WITH THE IDENTITY OF DEFENDERS 17 3. RECOMMENDATIONS 20 4. FURTHER DOCUMENTATION 22 INDEX: ACT 30/2765/2020 AUGUST 2020 LANGUAGE: ENGLISH amnesty.org 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The COVID-19 pandemic and states’ response to it have presented an array of new challenges and threats for those who defend human rights. In April 2020, Amnesty International urged states to ensure that human rights defenders are included in their responses to address the pandemic, as they are key actors to guarantee that any measures implemented respect human rights and do not leave anyone behind. The organization also called on all states not to use pandemic-related restrictions as a pretext to further shrink civic space and crackdown on dissent and those who defend human rights, or to suppress relevant information deemed uncomfortable to the government.1 Despite these warnings, and notwithstanding the commitments from the international community over two decades ago to protect and recognise the right to defend human rights,2 Amnesty International has documented with alarm the continued threats and attacks against human rights defenders in the context of the pandemic. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION OCTOBER 6, 2016 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 21–471 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate CHRISTOPHER H. SMITH, New Jersey, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Cochairman Chairman JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma ROBERT PITTENGER, North Carolina TOM COTTON, Arkansas TRENT FRANKS, Arizona STEVE DAINES, Montana RANDY HULTGREN, Illinois BEN SASSE, Nebraska DIANE BLACK, Tennessee DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIMOTHY J. WALZ, Minnesota JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio GARY PETERS, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California TED LIEU, California EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS CHRISTOPHER P. LU, Department of Labor SARAH SEWALL, Department of State DANIEL R. RUSSEL, Department of State TOM MALINOWSKI, Department of State PAUL B. PROTIC, Staff Director ELYSE B. ANDERSON, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 19:58 Oct 05, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 U:\DOCS\AR16 NEW\21471.TXT DEIDRE C O N T E N T S Page I. Executive Summary ............................................................................................. 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 1 Overview ............................................................................................................ 5 Recommendations to Congress and the Administration .............................. -

Daily Current Affair Quiz – 06.05.2019 to 08.05.2019

DAILY CURRENT AFFAIR QUIZ – 06.05.2019 TO 08.05.2019 DAILY CURRENT AFFAIR QUIZ : ( 06-08 MAY 2019) No. of Questions: 20 Correct: Full Mark: 20 Wrong: Time: 10 min Mark Secured: 1. What is the total Foreign Exchange B) Niketan Srivastava Reserves of India as on April 23, as per C) Arun Chaudhary the data by RBI? D) Vikas Verma A) USD 320.222 billion 8. Which among the following countries B) USD 418.515 billion will become the first in the world to C) USD 602.102 billion open the Crypto Powered City? D) USD 511.325 billion A) China 2. Name the newly appointed Supreme B) Nepal Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR) C) Malaysia of NATO? D) United States A) James G. Stavridis 9. Which of these network operators has B) Wesley Clark launched optical fibre-based high-speed C) Curtis M. Scaparrotti broadband service ‘Bharat Fibre’ in D) Tod D. Wolters Pulwama? 3. Which of these countries currency has A) Airtel been awarded with the best bank note B) BSNL for 2018 by the International Bank Note C) Reliance Society (IBNS) ? D) Vodafone A) Canada 10. Rani Abbakka Force is an all women B) India police patrol unit of which of these C) Singapore cities? D) Germany A) Srinagar 4. Maramraju Satyanarayana Rao who B) Pune passed away recently was a renowned C) Kolkata ___________ D) Mangaluru A) Judge 11. What was the name of the last captive B) Journalist White Tiger of Sanjay Gandhi National C) Writer Park (SGNP) that passed away recently? D) Scientist A) Bheem 5. -

Effect!Report!2015!

! ! ! ! ! EFFECT!REPORT!2015! ! ! Civil!Rights!Defenders!is!an!independent!expert!organisation!founded!in!Stockholm,!Sweden!in!1982,! with!the!aim!of!defending!human!rights,!and!in!particular!people’s!civil!and!political!rights,!and!to! support!and!empower!human!rights!defenders!at!risk.! ! ! 1.!What!does!your!organisation!want!to!achieve?! ! Civil!Rights!Defenders!is!a!nonBprofit!expert!human!rights!organisation!with!over!30!years’!experience! of!supporting!civil!society!and!strengthening!human!rights!defenders!(HRDs)!in!repressive!countries.! We!defend!people’s!civil!and!political!rights,!and!empower!HRDs!at!risk!in!Sweden!and!globally.!We! believe!a!strong!civil!society!is!crucial!for!an!independent!scrutiny!of!government!and!authorities!to! ensure! a! positive! development.! Therefore,! we! combine! human! rights! lobbying! and! advocacy! with! empowerment!of!our!partners.!! ! Together! with! partners,! we! monitor! human! rights! developments,! demand! reform,! justice! and! accountability.! We! support! HRDs! at! risk! by! providing! trainings,! technical! and! financial! assistance,! networking!platforms!and!peer!support.! ! Vision&and&long+term&targets& Civil!Rights!Defenders!overall!objective!is!to!improve!people’s!access!to!freedom!and!justice!through! improved!respect!for!their!civil!and!political!rights.!To!achieve!this!we!work!towards!the!following! goals:! ! People&are&empowered&to&claim&their&human&rights.& • People!get!increased!access!to!legal!aid.! • People!get!increased!access!to!information.! ! States&take&responsibility&for&the&fulfilment&of&human&rights.& -

Addressing the Challenges That Human Rights Defenders Face in the Context of Business Activities in an Age of a Shrinking Civil Society Space

Wednesday 18 November 10:00 to 11:20 Room XX (Building E) Addressing the challenges that Human Rights Defenders face in the context of business activities in an age of a shrinking civil society space There is a growing clampdown worldwide against human rights defenders who challenge specific economic paradigms, the presence of corporations and harmful business conduct. Too often, Governments detain human rights defenders, prevent them from raising funds, restrict their movements, place them under surveillance and, in some cases, authorize their torture and murder. Meanwhile, many companies either stand by as Governments employ tough law and order responses against defenders, or they aggressively target defenders who challenge their activities through legal or other means. Against this bleak backdrop, a number of progressive companies recognize the need and value in communicating effectively with communities affected by their projects. Without a social license to operate, companies face many problems that can affect their operations, increase a project’s costs and success and it can harm the firm’s overall reputation. The freedom human rights defenders enjoy plays an essential role in ensuring the legitimacy of a company’s operations. An open, secure civic space enables defenders to build inclusive, stable societies characterised by the rule of law that contribute to a favourable investment climate and operating conditions for companies. This session will explore how to overcome the risks that defenders, who challenge business conduct, face in a world in which civil society at large fights for its place. It will showcase the experiences of prominent defenders and companies operating in complex environments. -

20201110 Cuban Hrds –No Improvements

CUBAN HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS: “NO IMPROVEMENTS SINCE AGREEMENT WITH THE EU” Results from a survey with 110 Cuban Human Rights Defenders on how the human rights situation has evolved since the Political Dialogue and Cooperation agreement between Cuba and the European Union was signed in 2016, and what the European Union should do now. Published by: CIVIL RIGHTS DEFENDERS Stockholm 2020-11-11 We defend people’s civil and political rights and partner with human rights defenders worldwide. Östgötagatan 90, SE-116 64, Stockholm, Sweden +46 8 545 277 30 [email protected] www.crd.org Org. nr 802011-1442 Pg 90 01 29-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE SURVEY ............................................................................................................................ 3 RESULTS .................................................................................................................................. 3 1. ....... ALMOST EVERYONE WOULD LIKE TO BE PART OF THE DIALOGUE, BUT ONLY A FEW HAVE BEEN ABLE TO ENGAGE ................................................................... 3 2. ....... THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION IS DETERIORATING ........................................ 4 3. ....... CUBA IS NOT COMPLYING WITH THE POLITICAL DIALOGUE AND COOPERATION AGREEMENT ............................................................................................. 5 4. ....... THE EU NEEDS TO ACT .......................................................................................... 6 CONCLUSIONS ........................................................................................................................ -

Invitation: Virtual Roundtable Presentation of Issues Related to Human Rights and Youth in the Western Balkans and Turkey

Invitation: Virtual Roundtable Presentation of Issues Related to Human Rights and Youth in the Western Balkans and Turkey Irena Joveva MEP (Renew - Slovenia) and Civil Rights Defenders (CRD) cordially invite you to the second roundtable “What Worries Youth in Enlargement Countries: Human Rights and Youth in the Western Balkans and Turkey vol. 2” which will happen online. Date & Time: 28 January 2021, 10:30am-12:30pm CET Location: Zoom, event link to be sent after registration at this link Summary: Civil Rights Defenders (CRD) is an international human rights organisation based in Stockholm, which has been working in the Western Balkans for over 20 years, supporting the rule of law, freedom of expression, and anti-discrimination initiatives. On 28 January 2021, CRD is organising a virtual roundtable entitled “What Worries Youth in Enlargement Countries: Human Rights and Youth in the Western Balkans and Turkey vol. 2”, hosted by Irena Joveva MEP (Renew – Slovenia). During the event, youth activists from the Western Balkans and Turkey will present short policy papers, each on a human rights topic they believe affects youth in their respective countries. The policy papers highlight important issues such as affirmative action as a pathway to human rights, right to education for youth with disabilities, and constitutional challenges to the LGBTI+ movement. Topics by country: o Kevin Jasini (Albania): Challenges of the LGBTI+ Cause in Albania: From the Lack of Implementation to Violence and Rising Immigration o Sonja Kosanović (Bosnia and Herzegovina): -

2020 Human Rights Appeal

UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS APPEAL 2020 UNITED NATIONS HUMAN RIGHTS APPEAL 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. FOREWORD BY THE HIGH COMMISSIONER 4 2. UN HUMAN RIGHTS IN 2019 6 3. ROADMAP TO 2021 10 4. UN HUMAN RIGHTS AROUND THE WORLD IN 2020 38 5. FUNDING AND BUDGET 40 6. TRUST FUNDS 50 7. YOU CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE 52 8. ANNEXES 54 . OHCHR MANAGEMENT PLAN 2018-2021 - ELEMENTS FOCUSED ON CLIMATE CHANGE - ELEMENTS FOCUSED ON DIGITAL SPACE AND NEW TECHNOLOGIES - ELEMENTS FOCUSED ON CORRUPTION - ELEMENTS FOCUSED ON INEQUALITIES - ELEMENTS FOCUSED ON PEOPLE ON THE MOVE . UN HUMAN RIGHTS ORGANIZATION CHART . ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS UN HUMAN RIGHTS APPEAL 2020 3 FOREWORD BY THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOREWORD BY THE HIGH COMMISSIONER FOREWORD BY THE HIGH COMMISSIONER It is an honour to present the annual Human rights work is In the following pages, we outline the I believe that today’s challenges mean our appeal of my Office for 2020. My first year strategies and partnerships we are expertise is vitally needed. We appreciate as High Commissioner has reaffirmed my an investment. It is an devising to tackle these challenges. To the support we have received from our conviction that your political and financial investment many of you successfully deliver real human rights 78 donors in 2019, 63 of them being investment is crucial for the success impact in these areas, we know we also Member States. The US$172.1 million in our efforts to promote and protect have chosen to make, in need to align our organizational processes they provided to the Office constituted a human rights. -

Here Their Loved Ones Are Being Held

1 ACCESS DENIED Access Denied is a three-part report series that looks at the serious deterioration that has been happening to due process in China. This first volume,Access Denied: China’s Vanishing Suspects, examines the police practice of registering suspects under fake names at pre-trial detention centres, making it difficult or impossible for lawyers to access their clients or for families to know where their loved ones are being held. The second volume, Access Denied: China’s False Freedom, researches the ‘non-release release’ phenomenon, as first coined by US professor of law Jerome Cohen, in which prisoners, once freed from jail or a detention centre, continue to be arbitrarily confined by the police, usually at a secret location or at their home for weeks, months or even years. The final volume,Access Denied: China’s Legal Blockade, looks at the multitude of ways police employ to deny suspects legal assistance, including the use of threats or torture to force them into renouncing their own lawyer and accepting state-appointed counsel. About Safeguard Defenders Safeguard Defenders is a human rights NGO founded in late 2016. It undertakes and supports local field activities that contribute to the protection of basic rights, promote the rule of law and enhance the ability of local civil society and human rights defenders in some of the most hostile environments in Asia. https://safeguarddefenders.com | @safeguarddefend Access Denied: China’s Vanishing Suspects © 2020 Safeguard Defenders | Cover image by Antlem Published by Safeguard Defenders All rights reserved. This report may not be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in whole or in part by any means including graphic, electronic, or mechanical without expressed written consent of the publisher/author except in the case of brief quotations embodied in articles and reviews.