LEWIS-DISSERTATION-2018.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

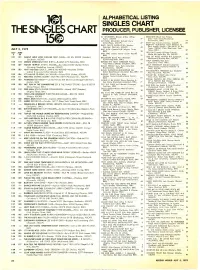

The Singles Chart

ALPHABETICAL LISTING 1 201 SINGLES CHART THE SINGLES CHART PRODUCER, PUBLISHER, LICENSEE AT SEVENTEEN Brooks Arthur (Mine/ MIDNIGHT BLUE Vini Poncia April, ASCAP) 77 (New York Times/Roumanian ATTITUDE DANCING Richard Perry Pickleworks, BMA) 14 15 (C'est/Maya, ASCAP) 47 MISTY Ray Stevens (Vernon, ASCAP) 23 BABY THAT'S BACKATCHA Smokey MORNIN' BEAUTIFUL Hank Medress & Dave Robinson (Bertram, ASCAP) 42 Appell (Apple Cider/Music of the Times, ASCAP; Little Max/New York JULY 5, 1975 BAD LUCK Gamble-Huff (Mighty Three, Times, BMI) 37 BMI) 39 JULY JUNE OLD DAYS James William Guercio BAD TIME Jimmy lenner (Cram Renraff, 5 28 (Make Me Smile/Big Elk, ASCAP) 52 BMI) 31 ONE OF THESE NIGHTS Bill Szymczyk 101 101 FUNNY HOW LOVE CAN BE FIRST CLASS-UK 5N 59033 (London) BALLROOM BLITZ Phil Wainman (Benchmark/Kicking Bear, ASCAP) 12 (Southern, ASCAP) (Chinnichap/RAK, BMI) 93 ONLY WOMEN Bob Ezrin BEFORE THE NEXT TEARDROP FALLS 102 110 DREAM MERCHANT NEW BIRTH-Buddah 470 (Saturday, BMI) (Ezra/Early Frost, BMI) 16 Huey Meaux (Shelby Singleton, BMI) 28 103 107 HONEY TRIPPIN' MYSTIC MOODS-Soundbird 5002 (Sutton Miller) ONLY YESTERDAY Richard Carpenter BLACK FRIDAY Gary Katz (American (Ginseng/Medallion Avenue, ASCAP) (Almo/Sweet Harmony/Hammer & Broadcasting, ASCAP) 43 Nails, ASCAP) 48 104 103 AIN'T NO USE COOK E. JARR & HIS KRUMS-Roulette 20426 BLACK SUPERMAN-MUHAMMAD ALI PHILADELPHIA FREEDOM Gus Dudgeon Robin Blanchflower Boy, BMI) 95 (Adam R. Levy & Father/Missile, BMI) (Drummer (Big Pig/Leeds, ASCAP) 54 105 104 IT'S ALL UP TO YOU JIM CAPALDI-Island D25 (Ackee, ASCAP) BURNIN' THING Gary Klein PLEASE MR. -

David Cassidy Press Release

PRESS RELEASE PROPERTY FROM THE CAREER OF DAVID CASSIDY TO HIT THE AUCTION BLOCK Los Angeles – On November 14th, highlights from the career of David Cassidy will begin their world tour at Hard Rock Cafe London, travel to New York and conclude with the auction at The Beverly Hilton in Los Angeles on December 16th. In 1970 The Partridge Family premiered, skyrocketing David Cassidy to superstardom. Cassidy had the #1 selling single of the year and became the consummate teen idol. His official fan club grew to become the largest in history, exceeding those of Elvis Presley and the Beatles. His career has continued to boast gold and platinum records, extremely successful Broadway, West End and Las Vegas shows, and tours that have broken box office records. Julien’s Auctions is pleased to announce a live and online auction of multiple items from the unprecedented career of David Cassidy with a portion of the proceeds benefiting the Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation and the Thoroughbred Charities of America providing a better life for thoroughbreds both during and after their careers. The beneficiary choices reflect Cassidy’s passion for thoroughbreds which he owns, breeds Manuel Design Jumpsuit and races. Melbourne Cricket Grounds (Est. $800/$1,200) The sale begins online November 10th at www.juliensauctions.com and will conclude live at The Beverly Hilton Hotel in Beverly Hills, CA December 16th, 2006. Highlights from this auction will tour Hard Rock Cafe London (November 14th – November 24th), Hard Rock Cafe New York (November 28th – December 1st) and Circa 55 in The Beverly Hilton Hotel, Beverly Hills, CA (December 11th – December 15th). -

BILTMORE ESTATE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service______National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BILTMORE ESTATE Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service_________________________________________National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Biltmore Estate (Additional Documentation and Boundary Reduction) Other Name/Site Number: N/A 2. LOCATION Street & Number: Generally bounded by the Swannanoa River on the north, the Not for publication: N/A paths of NC 191 and 1-26 on the west, the paths of the 1-25 and the Blue Ridge Parkway on the south, and a shared border with numerous property owners on the east; One Biltmore Plaza. City/Town: Asheville Vicinity: JC State: NC County: Buncombe Code: 021 Zip Code: 28801 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): __ Public-Local: _ District: X Public-State: _ Site: __ Public-Federal: Structure: __ Object: __ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 56 buildings 57 buildings 31 sites 25 sites 51 structures 30 structures _0_ objects 0 objects 138 Total 112 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: All Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: N/A NFS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 BILTMORE ESTATE Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this __ nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Eto in Me Wo 4E

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC/RECORD INDUSTRY .,,, 9yG03 2, Qqv ' 3 1%; SCe+ '3 13ç ..c, 3b GtJII,^<, A' JUNE 1, 1974 bd I J 1 I S t I I' ''1 HS l,-c t l eto in me wo 4e# THE STYUSTIr With A Bulleted Top Five Single ('You Make Me Feel Brand New') And An Album That Is The Record World Chartmaker Of The Week ('Let's Put It All Together'), This Avco Vocal Quintet From Philly Has Never Been Hotter. See Story On Page 24. SINGLES SLEEPERS ALBUMS HELEN REDDY, "YOU AND ME AGAINST THE SAMI JO, "IT COULD HAVE BEEN ME" (prod. "DIANA ROSS LIVE." There's no deny- WORLD" (prod. by Tom Catalano) by Sonny Limbo & Mickey Buckins/ ing Ms. Ross' hold on stardom, and (Almo, ASCAP). Mother -to -child song 1-2-3 Records) (Senor, ASCAP). this album is a testimony to the strength of reassurance hits so many lyrical Thrush who bowed onto the top of that grip. Whether with a medley O harmonics in these times, the Paul 40 stage with "Tell Me a Lie" of her hits of previous days, her Williams -Kenny Ascher tune already should have an even bigger hit in spirited rendering of "Corner Of The sounds Ike a classic. And who better this tale of love's triangle at the Sky" or with highlights of her "Lady to deliver it than the most consistent altar. Familiarity of the storyline Sings The Blues" effort, this lady's pop female vocal talent of the seven- takes on an interesting twist at the luminous power reigns supreme. -

Digital Commons @ Olivet

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Aurora-yearbook University Archives 1-1-1947 Aurora Volume 34 Paul Hubartt E( ditor) Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/arch_yrbks Part of the Graphic Communications Commons, Higher Education Commons, Photography Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Hubartt, Paul (Editor), "Aurora Volume 34" (1947). Aurora-yearbook. 34. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/arch_yrbks/34 This is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Aurora- yearbook by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. /) O L / U'ET N A Z A RENE COLLEGE 7 CONTENTS ^Itey eMeip.ed fcuilci OntellectualLf. B o cja U y PltuiicaliH GotnmefaUGMu ^ W h i i b r r t t c Olivet has produced many men and women whose careers have successfully served in the propagation of our religious beliefs and our educational standards. Although these careers have been widely varied, they all represent one dominant theme—that of building. The days that we, the present student body, have spent m these classrooms, and upon this campus, have also been used in building. Those days of training have come to an end for some of our number, but our build ing is not completed with graduation from college ; only the foundation has been laid. When we consider the immensity of the task that lies ahead, we begin to realize our indebtedness to Godly instructors genuinely interested in our building a suitable dwelling for the one who wrought the whole design—“Jesus Christ himself being the chief corner stone.’’ May the memories of the activities recorded in this volume be as rich as were the experiences themselves. -

Shelton Family History

SHELTON FAMILY HISTORY Descendant of John Shelton (born 1785) and Catherine (Messer) Shelton of Scott County, Virginia and Jackson County, Alabama BY ROBERT CASEY AND HAROLD CASEY 2003 SHELTON FAMILY HISTORY Second Edition First Edition (Shelton, Wininger and Pace Families): Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 87-71662 International Standard Book Number: 0-9619051-0-7 Copyright - 2003 by Robert Brooks Casey. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be duplicated or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the authors. This book may be reproduced in single quantities for research purposes, however, no part of this book may be included in a published book or in a published periodical without written permission of the authors. Additional copies of the 864 page book, “Shelton, Wininger and Pace Families,” are available for $35.00 postage paid from: Robert Casey, 4705 Eby Lane Austin, TX 78731-4705 SHELTON FAMILY HISTORY 4-3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............... 4-1-4-11 John Shelton (1) .............. 4-12 - 4-14 Martin Shelton (1.2) ............. 4-14 - 4-15 John W. Shelton (1.2.2) ............ 4-15 - 4-16 Martha A. Shelton (1.2.3) ........... 4-16 - 4-17 David Shelton (1.2.4) ............. 4-17 - 4-18 William Barker Shelton (1.2.4.1) ......... 4-19 - 4-33 James Logan Shelton (1.2.4.3) .......... 4-34 - 4-37 Elizabeth (Shelton) Bussell (1.2.4.5) ........ 4-37 - 4-38 Stephen Martin Shelton (1.2.4.6) ......... 4-38 - 4-42 Robert A. D. Shelton (1.2.4.7) .......... 4-42 - 4-43 Henry Clinton Shelton (1.2.4.8) ......... -

R Í, the Opry House, Formerly the Ryman ^:' Known to Millions As 3 Auditorium,

DEDICATED TO THE NEEDS OF THE MUSIC/RECORD INDUSTRY -- ,-_ (- ; 7\ f^ OCTOBER 20, 1973 3:r`j.,r F - Y' IN THE WORLD: , °S.'L+., 'Y:s. WHO E nnn mmmnminlmmmonnmnuunuuumuwmmmmummmmwuniuuunnnmuunm 1111111111n. / ) v V 1 yn COUNTRY MUSIC , r Í, The Opry House, Formerly The Ryman ^:' Known To Millions As 3 Auditorium, -. r The Home Of WSM Radio's Grand Ole Opry House Since 1941, Has Stood As A Country Music Landmark. The Venerable And Historic Edifice, y In 1891 Is In Its Last Days Of ; - Built , , . í o In This Special Issue, t Service. 5 - ^ Music '73 Record World Looks At Country I- The 48th Grand I' '-I ii In Conjunction With 1,< t- .' s ' Ole Opry Birthday Celebration. .r¡ - 9 M HITS OF THE WEEK HAS NO FRANK SINA1RA, "OL' BLUE EYES IS Frank LOGGINS & MESSINA, "MY MUSIC" RONSTADT, "LOVE eyes s W as (prod. by Jim Messina) (Jas- PRIDE" (prod. by John Boy - 2 BACK." Singing as wonderfully Noah returned to w.wI3eNryr perilla/Gnossos,ASCAP). Ian) (Walden/Glasco, ASCAP). ever, Frank iinatra has Sed b]íMin m collection hNy Long-awaited single from Taken from her beautiful new record ng witn a marvelous Q produced by Don J that dynamic duo has been album "Con't Cry Now," this of songs mas-erfully Gordon Jen- culled from -heir forthcoming Kaz-Titus classic has been per- Costa and arranged by hits include album. Written by both of formed tc tine hilt by Ms. Ron- kins. F'otentia multi -format Try and "Dream them, tune 's a cute rocker stadt. -

COMMENCEMENT PROGRAM Friday, December 15,2000

+ MISSION STATEMENT + ontbonne College is a coeducational institution of higher • encouraging dialogue among diverse communities Plearning dedicated to the discovery, understanding, • demonstrating care and dignity for each member of the preservation, and dissemination of truth. Fontbonne seeks community to educate students to think critically, to act ethically, and to • serving the larger community assume responsibility as citizens and leaders. Fontbonne offers • preparing competent individuals who bring an ethical and both undergraduate and graduate programs in an atmosphere responsible presence to the world characterized by inclusion, open communication, and personal concern. The undergraduate programs provide a synthesis of PuRPOSES liberal and professional education. As a Catholic college Provide quality educational experiences that are dedicated to sponsored by the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet, the discovery, understanding, preservation, and dissemination Fontbonne is rooted in the Judaeo-Christian tradition. of truth as a Catholic college rooted in the spirit of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet. VALUES Strive for excellence in the liberal arts and professional Fontbonne College continues the heritage of the Sisters of St. undergraduate and graduate programs in a diverse Joseph by fostering the values of quality, respect, diversity, atmosphere characterized by inclusion, open communication, community, justice, service, faith, and Catholic presence. respect and personal concern. Seek on-going institutional improvement through assessment, COMMITMENT self-reflection, planning and implementation. Fontbonne College is committed to: Build a diverse learning community through affiliations and • achieving educational excellence partnerships with educational and health care • advancing historical remembrance, critical reflection, institutions, industry and other organizations. and moral resolve Welcome to the Dunham Student Activity Center for Fontbonne's 2000 Winter Commencement. -

Obituaries for Cookeville City Cemetery N

OBITUARIES FOR COOKEVILLE CITY CEMETERY & additional information N – S (Compiled by Audrey J. (Denny) Lambert for her website at: http://www.ajlambert.com ) Sources: Putnam County Cemeteries by Maurine Ensor Patton & Doris (Garrison) Gilbert; Allison Connections by Della P. Franklin, 1988; Boyd Family by Carol Bradford; Draper Families in America, 1964; census records;Putnam County Herald & Herald•Citizenobts; Tennessee DAR GRC report, S1 V067: City Cemetery Cookeville, Putnam Co., TN, 1954; names, dates and information obtained from tombstones and research by Audrey J. (Denny) Lambert and others. Anthony Ray Nabors Obt. b. 25 March 1962, Cookeville, TN – d. 8 December 2006, Cookeville, TN, s/oJ. R. Nabors & Juanita Alcorn. COOKEVILLE •• Funeral services for Anthony Ray Nabors, 44, of Cookeville, will be held at 2 p.m. Sunday, Dec. 10, from the chapel of Whitson Funeral Home. Burial will be in Cookeville City Cemetery. The family will receive friends from 7 a.m. until time of services today at the funeral home. Mr. Nabors died Friday, Dec. 8, 2006, in Cookeville Regional Medical Center. He was born March 25, 1962, in Cookeville to J.R. and Juanita Alcorn Nabors of Cookeville. Mr. Nabors was self•employed in sales most of his life. He was employed by O' Charley's in Cookeville at the time of his death. He attended Trinity Assembly in Algood. He was an accomplished musician and a graduate of Belmont University in Nashville. In addition to his parents, his family includes a brother and sister•in•law, Wayne and Jan Nabors of Cookeville; a nephew, Blake Nabors of Cookeville; a special aunt, Joyce Alcorn Hall of Hendersonville; special uncles and aunts; and a very special friend, Mark Bice of Atlanta, Ga. -

Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons

Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons The Great R&B Files (# 8 of 12) Updated December 27, 2018 Transitions from Rhythm to Soul _ Twelve Original Soul Icons Presented by Claus Röhnisch The R&B Pioneers Series - Volume Eight of twelve page 1 (74) The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Eight of twelve Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons Yes – it’s Jackie The R&B Pioneers Series: find them all at The Great R&B-files Created by Claus Röhnisch http://www.rhythm-and-blues.info Top Rhythm & Blues Records – The Top R&B Hits from the classic years of Rhythm & Blues THE Blues Giants of the 1950s – Twelve Great Legends THE Top Ten Vocal Groups of the Golden´50s – Rhythm & Blues Harmony Ten Sepia Super Stars of Rock ‘n’ Roll – Idols Making Music History Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul icons The True R&B Pioneers - Twelve Hit-Makers from the Early Years Predecessors of the Soul Explosion in the 1960s - Twelve Famous Favorits The Clown Princes of Rock and Roll: The Coasters The John Lee Hooker Session Discography - The World’s Greatest Blues Singer with Year-By-Year Recap Those Hoodlum Friends – THE COASTERS The R&B Pioneers Series – The Top 30 Favorites Clyde McPhatter – the Original Soul Star 2 The R&B Pioneers Series – Volume Eight of twelve Transitions from Rhythm to Soul – Twelve Original Soul Icons Introduction As you may have noticed, the performers presented in the R&B Pioneers series are concentrated very much to the Golden Decade of the 1950s. -

Finally...The Glove Fits! VASE in Social Media Show Afterglow

Hello VASE fans, good to have you back. We have another Melbourne Guitar show behind us and would like to welcome any new friends made there. This month’s theme could be SYNERGY, as we continue to experience that in interacting with others, we continue to accomplish things together greater than the sum of the individual efforts involved. This is demonstrated by our dealings with the Glove Amplifier folks, the serendipity of Mark Lewis taking such an active part in our Guitar Show experience; this month’s VIP Jason Castle as an example (there are many) of super supporters, and of course all the wonderful performers and technical folks who take the time to share photos and VASE experiences. Read on. The Glove Fits! VASE was introduced to Glove Amplifier Covers by Alex Pavlis (pictured at right), the Melbourne Guitar Show winner in 2015 of the VASE Tonesetter 18 Combo. He got on to Matt Cowie at Glove Amplifier & Speaker Covers in Castle Hill NSW, supplied some dimensions and a cover was made for his new amp. Alex was very pleased with his purchase and sent us pictures. Alex Pavlis We have since been in touch with Glove (and with Matt’s Dad Steve, who founded the company) and are happy to pass along their information to you. Steve has measured up the VASE boxes and can supply covers for any of the Tonesetter range. And yes, they fit like a glove! They were at the recent Melbourne Guitar Show and graciously supplied a cover to this year’s winner of the Tonesetter 18 Combo, Mark Marzook. -

The Partridge Family the Partridge Family Notebook Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Partridge Family The Partridge Family Notebook mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Stage & Screen Album: The Partridge Family Notebook Country: US Released: 1972 Style: Vocal MP3 version RAR size: 1320 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1869 mb WMA version RAR size: 1390 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 590 Other Formats: AU MP4 AUD AA VOX APE WMA Tracklist Hide Credits Friend And A Lover A1 2:29 Written-By – Bobby Hart, Danny Janssen, Wes Farrell Walking In The Rain A2 2:58 Written-By – Barry Mann-Cynthia Weil*, Phil Spector Take Good Care Of Her A3 2:42 Written-By – Bobby Hart, Danny Janssen Together We're Better A4 2:38 Written-By – Ken Jacobson, Tony Romeo Looking Through The Eyes Of Love A5 3:03 Written-By – Barry Mann-Cynthia Weil* Maybe Someday A6 2:56 Written-By – Austin Roberts, John Michael Hill* We Gotta Get Out Of This Place B1 3:55 Written-By – Barry Mann-Cynthia Weil* Storybook Love B2 2:42 Written-By – Adam Miller, Wes Farrell Love Must Be The Answer B3 3:10 Written-By – Peggy Clinger-Johnny Cymbal*, Wes Farrell Something's Wrong B4 3:12 Written-By – Bobby Hart, Danny Janssen, Wes Farrell As Long As You're There B5 3:04 Written-By – Adam Miller Credits Backing Vocals – Bahler Brothers, Jackie Ward, Ron Hicklin, Shirley Jones Backing Vocals [Uncredited] – Jerry Whitman (tracks: A1, A2, A6), Tom Bahler (tracks: A1, A2, A6) Bass – Joe Osborne*, Max Bennett Drums – Hal Blaine Guitar – Dennis Budimir, Larry Carlton, Louis Shelton*, Tommy Tedesco Keyboards – Larry Knechtel, Mike Melvoin Lead Vocals – David Cassidy Producer – Wes Farrell Notes Label variant is smooth, no indent and has R113890A above the regular Category and 1111-SA-BW under Bell-1111.