Distance Education During COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What's News at Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC What's News? Newspapers 12-13-1993 What's News At Rhode Island College Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news Recommended Citation Rhode Island College, "What's News At Rhode Island College" (1993). What's News?. 474. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news/474 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in What's News? by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WHAT'S NEWS AT RHODE ISLAND COLLEGE Vol. 14 Issue 8 Circulation over 35,000 December 13, 1993 'Taki' Votoras, 95 others From one alumnus to another- honored for their service SupportHigher Education and Adams Library by George LaTour nized for 10, 15, 20 and 25 years of service were on hand. What's News Associate Editor President Nazarian, himself able to boast of nearly 40 years in the encouragement to all alumni seek anajotis T. "Taki" Votoras of service of the College (second only to by Clare Eckert ing further support for the raffle. the English faculty, upon Chester E. "Chet" Smolski, a profes What's News Editor The mailing will go out within the being added to the honor role sor of geography, who does have 40) next few days. Enclosed will be two of 30-year employees at the informed those present for the 10- books of raffle tickets and a return, annualP Service Recognition Day Dec. -

Canais Fibra Fora De SP

menu Regionais IPTV Alfenas - MG 513 TV Cultura HD 514 TV Alterosa HD - SBT 515 EPTV Sul de Minas HD - TV Globo 516 TV Rede Mais Varginha HD - Record 517 RedeTV! HD 519 Band Minas BH HD 527 TV Gazeta HD 586 Record News *Abertos (obrig. I): Canais de programação de distribuição obrigatória (Art 52, I, Resolução 581/2012 Anatel) e não fazem parte dos Planos de Serviços e podem ser alterados conforme demanda de regulamentação. **Públicos (obrig. II): Canais de programação de distribuição obrigatória (Art 52, II ao XI, Resolução 581/2012 Anatel) e não fazem parte dos Planos de Serviços e podem ser alterados conforme demanda de regulamentação. Para consultar valores dos Canais a la carte clique aqui. A transmissão de alguns canais abertos poderá ser suspensa por tempo indeterminado em algumas cidades em virtude do encerramento do sinal analógico. menu Regionais IPTV Alvorada - RS 513 TV Cultura HD 514 SBT RS HD 515 RBS TV HD - TV Globo 516 Record RS HD 517 TV Pampa HD - Rede TV 519 Band RS HD 527 TV Gazeta HD 586 Record News menu Regionais IPTV Anápolis - GO 513 TV Cultura HD 514 TV Serra Dourada HD - SBT 515 TV Anhanguera Anápolis HD - TV Globo 516 TV Goiás HD - Record 517 RedeTV! HD 519 TV Goiânia HD - Band 527 TV Gazeta HD 586 Record News menu Regionais IPTV Aparecida de Goiânia - GO 513 TV Cultura HD 514 TV Serra Dourada HD - SBT 515 TV Anhanguera Goiânia HD - TV Globo 516 TV Goiás HD - Record 517 TV Brasília HD - Rede TV 519 TV Goiânia HD - Band 527 TV Gazeta HD 586 Record News menu Regionais IPTV Apucarana - PR 513 TV Cultura HD -

What's News at Rhode Island College Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC What's News? Newspapers 10-13-2008 What's News At Rhode Island College Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news Recommended Citation Rhode Island College, "What's News At Rhode Island College" (2008). What's News?. 92. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news/92 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in What's News? by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. October 13,3, 22008008 VVol.ol. 2299 IIssuessue 2 WHAT’S NEWS @ Rhode Island College Established in 1980 Circulation over 52,000 RIC, URI receive $12.5 million National Science Foundation grant By Rob Martin of chemistry at RIC and a lead Managing Editor principal investigator on the project, A project based at Rhode Island known at RITES (Rhode Island College and the University of Rhode Technology Enhanced Science). Island to improve science learning at Gov. Donald L. Carcieri the middle and secondary levels in announced the grant award at Rhode Island has received a $12.5 a ceremony at Johnston Senior million grant from the National High School on Sept. 25. Science Foundation (NSF) – the Carcieri commended the state’s largest such grant ever awarded in higher education institutions for Rhode Island. The project will be establishing a “great sense of administered in schools statewide camaraderie” and “aggressively through the newly established collaborating” with Rhode Rhode Island STEM (science, Island’s K-12 school system. -

Sign Language Ideologies: Practices and Politics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Heriot Watt Pure Annelies Kusters, Mara Green, Erin Moriarty and Kristin Snoddon Sign language ideologies: Practices and politics While much research has taken place on language attitudes and ideologies regarding spoken languages, research that investigates sign language ideol- ogies and names them as such is only just emerging. Actually, earlier work in Deaf Studies and sign language research uncovered the existence and power of language ideologies without explicitly using this term. However, it is only quite recently that scholars have begun to explicitly focus on sign language ideologies, conceptualized as such, as a field of study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first edited volume to do so. Influenced by our backgrounds in anthropology and applied linguistics, in this volume we bring together research that addresses sign language ideologies in practice. In other words, this book highlights the importance of examining language ideologies as they unfold on the ground, undergirded by the premise that what we think that language can do (ideology) is related to what we do with language (practice).¹ All the chapters address the tangled confluence of sign lan- guage ideologies as they influence, manifest in, and are challenged by commu- nicative practices. Contextual analysis shows that language ideologies are often situation-dependent and indeed often seemingly contradictory, varying across space and moments in time. Therefore, rather than only identifying language ideologies as they appear in metalinguistic discourses, the authors in this book analyse how everyday language practices implicitly or explicitly involve ideas about those practices and the other way around. -

Os 50 Anos Da Televisão Em Santa Catarina: Concentração De Mídia E De Audiência1

ISSN 2175-6945 Os 50 anos da televisão em Santa Catarina: concentração de mídia e de audiência1 Carlos Roberto Praxedes dos SANTOS2 Universidade do Vale do Itajaí (Univali) Lilian Carla MUNEIRO3 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN) Resumo Até 1969, o Estado de Santa Catarina não possuía qualquer geradora de televisão. Durante os anos de 1970 e 1979, haviam apenas dois canais no Estado. No final daquela década, outros três canais entram em operação. Já a década de 1980 registra a maior expansão da TV. Atualmente, 15 emissoras comerciais estão em operação, além de 9 TVs não comerciais. Por este motivo, este trabalho tem o objetivo de resgatar a história das 24 geradoras de televisão de Santa Catarina, identificando as alterações de trocas de acionistas, de nome da emissora e de retransmissão de cabeça-de-rede ao longo do tempo. Conclui-se que a maior parte das emissoras comerciais está concentrada nas mãos de apenas dois grupos de comunicação, além do atraso na chegada da televisão não comercial ao Estado de Santa Catarina, com a primeira iniciativa apenas tendo sido implantada em 1994. Palavras-chave: História; Radiodifusão; Televisão; Santa Catarina. Introdução Quando se observa que o Brasil possui atualmente cerca de 500 geradoras de televisão, pode-se afirmar que o Estado de Santa Catarina possui um número bastante reduzido de canais. Além disso, é possível perceber que a distribuição destas estações se dá de forma concentrada nas principais cidades do Estado como a capital, Florianópolis; Joinville, maior cidade do Estado, além dos municípios de Blumenau, Lages, Joaçaba, Xanxerê, Criciúma, Rio do Sul, Itajaí e Chapecó. -

What's News at Rhode Island College Rhode Island College

Rhode Island College Digital Commons @ RIC What's News? Newspapers 9-23-2003 What's News At Rhode Island College Rhode Island College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news Recommended Citation Rhode Island College, "What's News At Rhode Island College" (2003). What's News?. 41. https://digitalcommons.ric.edu/whats_news/41 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Digital Commons @ RIC. It has been accepted for inclusion in What's News? by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ RIC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. What’s News at Rhode Island College Vol. 24 Issue 2 Circulation over 47,000 Sept. 29, 2003 Highlights First-year student admissions reach an all-time high In the News Freshman class largest in 150 years! RIC freshman class is largest in 150 years by Rob Martin Michael Iannone — survivor What’s News Associate Editor of the Station Nightclub fire — returns to RIC hode Island College is the Student Union back in place to be in 2003 – at least business Raccording to the latest admis- sions report showing the College October Series examines: has broken all previous records for Constantly Contesting Art incoming freshman class size. Compared with 2002, the num- ber of admissions (based on paid Features deposits) for this year is up 7.5 percent for freshmen (1,200). Also College of Arts & Sciences up this year are the number of names distinguished transfer/second degree/re-admit- faculty ted students (837), and overall Yael Avissar receives new students (2,037). -

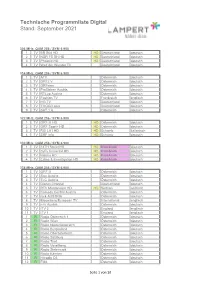

Technische Programmliste Digital Stand: August 2021

Technische Programmliste Digital Stand: September 2021 306 MHz, QAM 256 / SYM 6.900 1 TV BR Süd HD HD Deutschland deutsch 2 TV NDR FS SH HD HD Deutschland deutsch 3 TV Phoenix HD HD Deutschland deutsch 4 TV Welt der Wunder TV Deutschland deutsch 314 MHz, QAM 256 / SYM 6.900 1 TV ATV Österreich deutsch 2 TV ORF2 V Österreich deutsch 3 TV ORFeins Österreich deutsch 4 TV ProSieben Austria Österreich deutsch 5 TV RTLup Austria Österreich deutsch 6 TV Fashion TV Frankreich englisch 7 TV HG TV Deutschland deutsch 8 TV TOGGO plus Deutschland deutsch 9 TV SAT.1 A Österreich deutsch 322 MHz, QAM 256 / SYM 6.900 1 TV ORF III HD HD Österreich deutsch 2 TV ORF Sport+ HD HD Österreich deutsch 3 TV RSI LA1 HD HD Schweiz italienisch 4 TV SRF Info HD Schweiz deutsch 330 MHz, QAM 256 / SYM 6.900 1 TV 13TH Street HD HD Kabelkiosk deutsch 2 TV SyFy Universal HD HD Kabelkiosk deutsch 3 TV History HD HD Kabelkiosk deutsch 4 TV Crime & Investigation HD HD Kabelkiosk deutsch 338 MHz, QAM 256 / SYM 6.900 1 TV ORF III Österreich deutsch 2 TV Sixx Austria Österreich deutsch 3 TV TLC Austria Österreich deutsch 4 TV Disney Channel Deutschland deutsch 5 TV RTV Montenegro HD HD Serbien serbisch 6 TV Comedy Central Austria Österreich deutsch 7 TV nick AUSTRIA Österreich deutsch 8 TV Bloomberg European TV International englisch 9 TV n-tv Austria Österreich deutsch 10 TV ITV 2 England englisch 11 TV ITV 1 England englisch 1 R Radio Österreich 1 Österreich deutsch 2 R Radio Wien Österreich deutsch 3 R Radio Niederösterreich Österreich deutsch 4 R Radio Burgenland Österreich -

Anthropology N Ew Sletter

Special Theme: Where Sign Language Studies Can Take Us National Introductory Essay: Museum of Sign Languages are Languages! Ethnology Osaka Ritsuko Kikusawa Number 33 National Museum of Ethnology December 2011 On November 25, 2009, the Nagoya District Court in Japan sustained a claim by Newsletter Anthropology a Japanese Sign Language (JSL) user, acknowledging that sign languages are a means of communication that are equal to orally spoken languages. Kimie Oya, a Deaf signer, suffered from physical problems on her upper limbs as the result of injuries sustained in a traffic accident. This restricted her ability to express MINPAKU things in JSL. However, the insurance company did not admit that this should be compensated as a (partial) loss of linguistic ability, because ‘whether to use a sign language or not is up to one’s choice’. Although some thought that the degree of impairment admitted by the court (14% loss) was too low, the sentence was still welcome and was considered a big step forward toward the better recognition of JSL, the language of the biggest minority group in Japan. Contents A correct understanding of the nature of sign languages, and recognition that they are real Where Sign Language languages is spreading slowly but Studies Can Take Us steadily through society. Signing Ritsuko Kikusawa communities, meanwhile, have Introductory Essay: continued to broaden their worldview, Sign Languages are Languages! ....... 1 reflecting globalization, and cooperation with linguists to acquire Soya Mori objective analyses and descriptions of Sign Language Studies in Japan and their languages (see Mori article, this Abroad ............................................ 2 issue). I believe that the situation is more or less similar in many countries Connie de Vos and societies — the communities of A Signers’ Village in Bali, Indonesia linguists being no exception. -

Samsung TV Plus

Samsung TV Plus Channel Descriptions UK | 18th November 2020 Channel Description Info Samsung Name Logo Genre Summary TV Plus # Art/Music/Surf/Skate/Snow — the five pillars of the Absinthe Films Sports & Outdoors 4071 foundation that is boardsport culture. Action Movies – Rakuten TV Movies Movies to keep you on the edge of your seat. 4504 The crown jewels of drama, All Drama is brimming with All Drama Entertainment 4256 classic TV from the last decade. In Big Name, discover fascinating biopics that retrace the history of the great names of humanity. (Re) discover the Big Name Entertainment 4257 history of those who have stood out notably for our greatest good ... or our greatest misfortune. Bloomberg TV+ UHD delivers Live 24x7 global business and markets news, data, analysis, and stories from Bloomberg Bloomberg TV+ News 4007 News and Businessweek – available in a 4K ultra high definition (UHD) viewing experience. Samsung brings you a mix of great UK and US comedy content, from Russell Howard telling you Good News to Comedy Movies 4001 chuckling along to the best bits of Taskmaster. Comedy – It’s a Laughing Matter! Comedy Movies – Rakuten Movies Amusing, lighthearted movies to keep your spirits high. 4002 TV Deluxe Lounge – the relaxed sound for a good feeling. Your time, your break: to come down, take a deep breath and take Deluxe Lounge HD Music 4451 a break. Urbanauts, lounge lizards meet lounge-like tracks and smooth bar-grooves - the lounge mix. Head off, music on! The world’s best platform for quality short form entertainment! Watch short movies, documentaries, comedies discover.film Movies 4507 & dramas, featuring known Hollywood stars and emerging talent. -

Providing Quality Education for Children with Disabilities in Developing Countries: Possibilities and Limitations of Inclusive Education in Cambodia

Providing Quality Education for Children with Disabilities in Developing Countries: Possibilities and Limitations of Inclusive Education in Cambodia 発展途上国における障害児教育の提供 -カンボジアにおけるインクルーシブ教育の可能性と限界― DIANA KARTIKA Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in International Studies Graduate School of Asia-Pacific Studies Waseda University © 2017 Diana Kartika All Rights Reserved SUMMARY Located within the two fields of disability studies and education development, this empirical study sheds light on the forces facilitating and hindering the education and development of children with disabilities (CwDs) in a developing country context and seeks to provide a universal framework for examining the complexities of inclusive education. Based on Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological systems theory, this study analyses the influence of actors and processes in Cambodia at the bio-, micro-, meso-, exo-, and chrono-levels, on access and quality of education for CwDs. It then identifies ecological niches of possibilities that capitalise on the strengths of local communities, for effective and sustainable intervention in Cambodia. This study was conducted in Battambang, Kampot, Kandal, Phnom Penh, and Ratanakiri in February and July 2015. A total of 88 interviews were conducted with 119 respondents: 50 individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with parents at their homes, 19 focus group interviews were conducted with 50 teachers, and 19 individual semi-structured interviews were conducted with school directors in schools. Participatory observations were also carried out at 50 homes, 6 classes, and 19 schools. Secondary empirical quantitative data and findings from Kuroda, Kartika, and Kitamura (2017) were also used to lend greater validity to this study. Findings revealed that CwDs can act as active social agents influencing their own education; developmental dispositions have a direct relationship on this influence. -

Applied Linguistics Review

Heriot-Watt University Research Gateway Deaf people with “no language”: Mobility and flexible accumulation in languaging practices of deaf people in Cambodia Citation for published version: Moriarty Harrelson, E 2017, 'Deaf people with “no language”: Mobility and flexible accumulation in languaging practices of deaf people in Cambodia', Applied Linguistics Review. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0081 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1515/applirev-2017-0081 Link: Link to publication record in Heriot-Watt Research Portal Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Applied Linguistics Review Publisher Rights Statement: This is the accepted version of the following article: Moriarty Harrelson, E. (2017). Deaf people with “no language”: Mobility and flexible accumulation in languaging practices of deaf people in Cambodia . Applied Linguistics Review, which has been published in final form at doi:10.1515/applirev-2017-0081 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via Heriot-Watt Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy Heriot-Watt University has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the content in Heriot-Watt Research Portal complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to -

Prayer Cards (216)

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Deaf in Afghanistan Deaf in Albania Population: 398,000 Population: 14,000 World Popl: 48,206,860 World Popl: 48,206,860 Total Countries: 216 Total Countries: 216 People Cluster: Deaf People Cluster: Deaf Main Language: Afghan Sign Language Main Language: Albanian Sign Language Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.05% Chr Adherents: 30.47% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Translation Needed www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Deaf in Algeria Deaf in American Samoa Population: 223,000 Population: 300 World Popl: 48,206,860 World Popl: 48,206,860 Total Countries: 216 Total Countries: 216 People Cluster: Deaf People Cluster: Deaf Main Language: Algerian Sign Language Main Language: Language unknown Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Christianity Status: Unreached Status: Superficially reached Evangelicals: Unknown % Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 0.28% Chr Adherents: 95.1% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Unspecified www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Deaf in Andorra Deaf in Angola Population: 200 Population: 339,000 World Popl: 48,206,860 World Popl: 48,206,860 Total