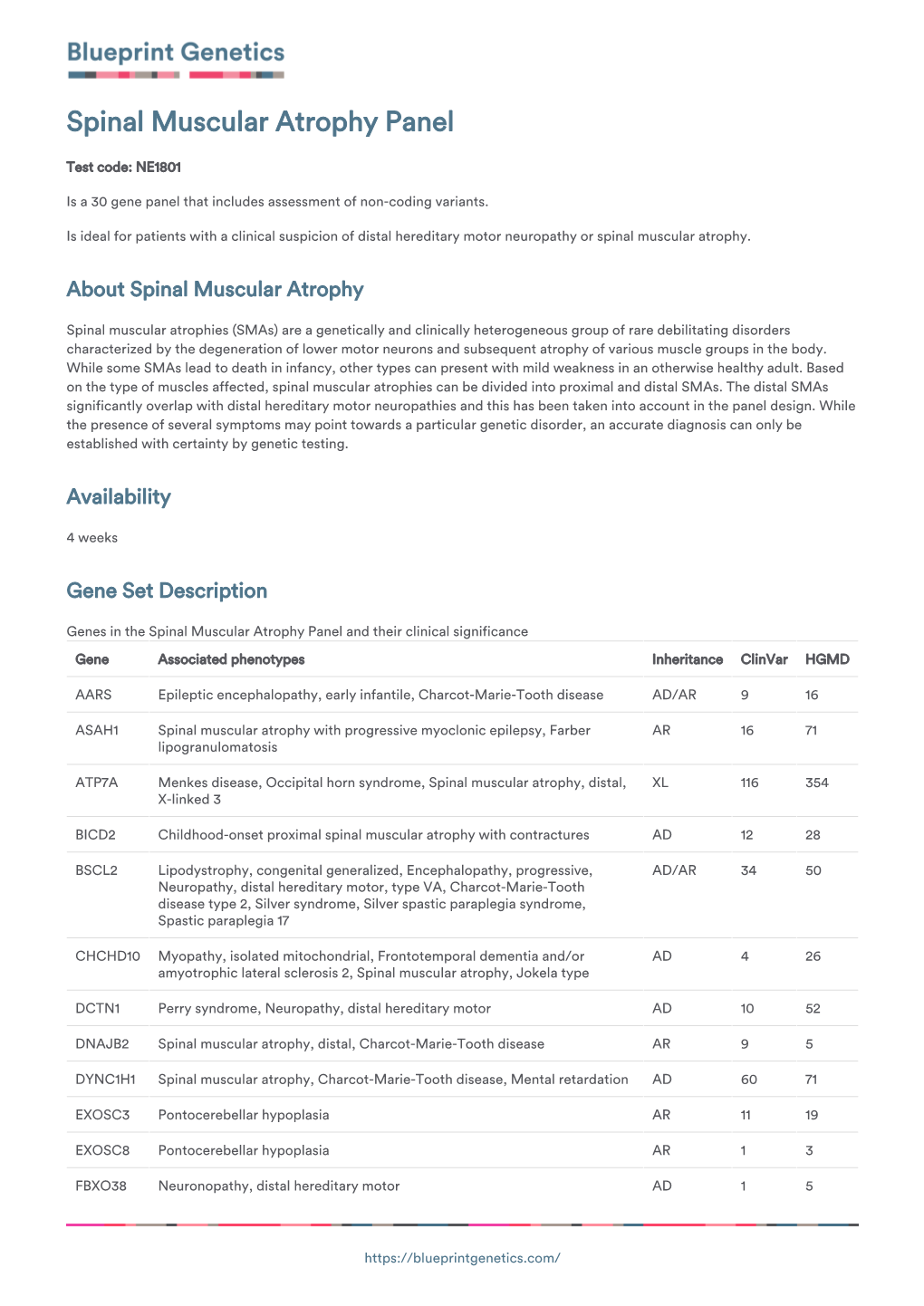

Blueprint Genetics Spinal Muscular Atrophy Panel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inherited Neuropathies

407 Inherited Neuropathies Vera Fridman, MD1 M. M. Reilly, MD, FRCP, FRCPI2 1 Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Diagnostic Center, Address for correspondence Vera Fridman, MD, Neuromuscular Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts Diagnostic Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, 2 MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases, UCL Institute of Neurology Massachusetts, 165 Cambridge St. Boston, MA 02114 and The National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, Queen (e-mail: [email protected]). Square, London, United Kingdom Semin Neurol 2015;35:407–423. Abstract Hereditary neuropathies (HNs) are among the most common inherited neurologic Keywords disorders and are diverse both clinically and genetically. Recent genetic advances have ► hereditary contributed to a rapid expansion of identifiable causes of HN and have broadened the neuropathy phenotypic spectrum associated with many of the causative mutations. The underlying ► Charcot-Marie-Tooth molecular pathways of disease have also been better delineated, leading to the promise disease for potential treatments. This chapter reviews the clinical and biological aspects of the ► hereditary sensory common causes of HN and addresses the challenges of approaching the diagnostic and motor workup of these conditions in a rapidly evolving genetic landscape. neuropathy ► hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy Hereditary neuropathies (HN) are among the most common Select forms of HN also involve cranial nerves and respiratory inherited neurologic diseases, with a prevalence of 1 in 2,500 function. Nevertheless, in the majority of patients with HN individuals.1,2 They encompass a clinically heterogeneous set there is no shortening of life expectancy. of disorders and vary greatly in severity, spanning a spectrum Historically, hereditary neuropathies have been classified from mildly symptomatic forms to those resulting in severe based on the primary site of nerve pathology (myelin vs. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Spinal Muscular Atrophy U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTHAND HUMAN SERVICES National Institutes of Health Spinal Muscular Atrophy What is spinal muscular atrophy? pinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a group Sof hereditary diseases that progressively destroys motor neurons—nerve cells in the brain stem and spinal cord that control essential skeletal muscle activity such as speaking, walking, breathing, and swallowing, leading to muscle weakness and atrophy. Motor neurons control movement in the arms, legs, chest, face, throat, and tongue. When there are disruptions in the signals between motor neurons and muscles, the muscles gradually weaken, begin wasting away and develop twitching (called fasciculations). What causes SMA? he most common form of SMA is caused by Tdefects in both copies of the survival motor neuron 1 gene (SMN1) on chromosome 5q. This gene produces the survival motor neuron (SMN) protein which maintains the health and normal function of motor neurons. Individuals with SMA have insufficient levels of the SMN protein, which leads to loss of motor neurons in the spinal cord, producing weakness and wasting of the skeletal muscles. This weakness is often more severe in the trunk and upper leg and arm muscles than in muscles of the hands and feet. 1 There are many types of spinal muscular atrophy that are caused by changes in the same genes. Less common forms of SMA are caused by mutations in other genes including the VAPB gene located on chromosome 20, the DYNC1H1 gene on chromosome 14, the BICD2 gene on chromosome 9, and the UBA1 gene on the X chromosome. The types differ in age of onset and severity of muscle weakness; however, there is overlap between the types. -

Whole Exome Should Be Preferred Over Sanger Sequencing in Suspected Mitochondrial Myopathy

Neurobiology of Aging 78 (2019) 166e167 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurobiology of Aging journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/neuaging Letter to the editor Whole exome should be preferred over Sanger sequencing in suspected mitochondrial myopathy With interest we read the article by Rubino et al. about Sanger X-linked trait of inheritance, whole exome sequencing rather than sequencing of the genes CHCHD2 and CHCHD10 in 62 Italian pa- Sanger sequencing of single genes is recommended to detect the tients with a mitochondrial myopathy without a genetic defect underlying genetic defect. In case of a maternal trait of inheritance, (Rubino et al., 2018). The authors found the previously reported however, sequencing of the mtDNA is recommended. Whole exome variant c.307C>A in the CHCHD10 gene (Perrone et al., 2017)in1of sequencing is preferred over Sanger sequencing as myopathies or the 62 patients (Rubino et al., 2018). We have the following com- phenotypes in general that resemble an MID are in fact due to ments and concerns. mutations in genes not involved in mitochondrial functions, rep- If no mutation was found in 61 of the 62 included myopathy resenting genotypic heterogeneity. patients, how can the authors be sure that these patients had We do not agree that application of SIFT and polyphem 2 is indeed a mitochondrial disorder (MID). We should be informed on sufficient to confirm pathogenicity of a variant. Confirmation of the which criteria and by which means the diagnosis of an MID was pathogenicity requires documentation of the variant in other established in the 61 patients, who did not carry a mutation in the populations, segregation of the phenotype with the genotype CHCHD2 and CHCHD10 genes, respectively. -

A Novel De Novo 20Q13.32&Ndash;Q13.33

Journal of Human Genetics (2015) 60, 313–317 & 2015 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/15 www.nature.com/jhg ORIGINAL ARTICLE Anovelde novo 20q13.32–q13.33 deletion in a 2-year-old child with poor growth, feeding difficulties and low bone mass Meena Balasubramanian1, Edward Atack2, Kath Smith2 and Michael James Parker1 Interstitial deletions of the long arm of chromosome 20 are rarely reported in the literature. We report a 2-year-old child with a 2.6 Mb deletion of 20q13.32–q13.33, detected by microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization, who presented with poor growth, feeding difficulties, abnormal subcutaneous fat distribution with the lack of adipose tissue on clinical examination, facial dysmorphism and low bone mass. This report adds to rare publications describing constitutional aberrations of chromosome 20q, and adds further evidence to the fact that deletion of the GNAS complex may not always be associated with an Albright’s hereditary osteodystrophy phenotype as described previously. Journal of Human Genetics (2015) 60, 313–317; doi:10.1038/jhg.2015.22; published online 12 March 2015 INTRODUCTION resuscitation immediately after birth and Apgar scores were 9 and 9 at 1 and Reports of isolated subtelomeric deletions of the long arm of 10 min, respectively, of age. Birth parameters were: weight ~ 1.56 kg (0.4th–2nd chromosome 20 are rare, but a few cases have been reported in the centile), length ~ 40 cm (o0.4th centile) and head circumference ~ 28.2 cm o fi literature over the past 30 years.1–13 Traylor et al.12 provided an ( 0.4th centile). -

Plekhg5-Regulated Autophagy of Synaptic Vesicles Reveals a Pathogenic Mechanism in Motoneuron Disease

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Medicine Faculty Papers Department of Medicine 12-1-2017 Plekhg5-regulated autophagy of synaptic vesicles reveals a pathogenic mechanism in motoneuron disease. Patrick Lüningschrör University Hospital Würzburg; University of Bielefeld Beyenech Binotti Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry, Göttingen Benjamin Dombert University Hospital Würzburg Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/medfp Peter Heimann Univ Persityart of of the Bielef Neureldology Commons AngelLet usPerez-Lar knowa how access to this document benefits ouy University of Bielefeld Recommended Citation Lüningschrör, Patrick; Binotti, Beyenech; Dombert, Benjamin; Heimann, Peter; Perez-Lara, Angel; See next page for additional authors Slotta, Carsten; Thau-Habermann, Nadine; von Collenberg, Cora R.; Karl, Franziska; Damme, Markus; Horowitz, Arie; Maystadt, Isabelle; Füchtbauer, Annette; Füchtbauer, Ernst-Martin; Jablonka, Sibylle; Blum, Robert; Üçeyler, Nurcan; Petri, Susanne; Kaltschmidt, Barbara; Jahn, Reinhard; Kaltschmidt, Christian; and Sendtner, Michael, "Plekhg5-regulated autophagy of synaptic vesicles reveals a pathogenic mechanism in motoneuron disease." (2017). Department of Medicine Faculty Papers. Paper 220. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/medfp/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Medicine Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. -

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared with Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant

Appendix 2. Significantly Differentially Regulated Genes in Term Compared With Second Trimester Amniotic Fluid Supernatant Fold Change in term vs second trimester Amniotic Affymetrix Duplicate Fluid Probe ID probes Symbol Entrez Gene Name 1019.9 217059_at D MUC7 mucin 7, secreted 424.5 211735_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 416.2 206835_at STATH statherin 363.4 214387_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 295.5 205982_x_at D SFTPC surfactant protein C 288.7 1553454_at RPTN repetin solute carrier family 34 (sodium 251.3 204124_at SLC34A2 phosphate), member 2 238.9 206786_at HTN3 histatin 3 161.5 220191_at GKN1 gastrokine 1 152.7 223678_s_at D SFTPA2 surfactant protein A2 130.9 207430_s_at D MSMB microseminoprotein, beta- 99.0 214199_at SFTPD surfactant protein D major histocompatibility complex, class II, 96.5 210982_s_at D HLA-DRA DR alpha 96.5 221133_s_at D CLDN18 claudin 18 94.4 238222_at GKN2 gastrokine 2 93.7 1557961_s_at D LOC100127983 uncharacterized LOC100127983 93.1 229584_at LRRK2 leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 HOXD cluster antisense RNA 1 (non- 88.6 242042_s_at D HOXD-AS1 protein coding) 86.0 205569_at LAMP3 lysosomal-associated membrane protein 3 85.4 232698_at BPIFB2 BPI fold containing family B, member 2 84.4 205979_at SCGB2A1 secretoglobin, family 2A, member 1 84.3 230469_at RTKN2 rhotekin 2 82.2 204130_at HSD11B2 hydroxysteroid (11-beta) dehydrogenase 2 81.9 222242_s_at KLK5 kallikrein-related peptidase 5 77.0 237281_at AKAP14 A kinase (PRKA) anchor protein 14 76.7 1553602_at MUCL1 mucin-like 1 76.3 216359_at D MUC7 mucin 7, -

1 Cerebrospinal Fluid Neurofilament Light Is Associated with Survival In

1 Cerebrospinal fluid Neurofilament Light is associated with survival in mitochondrial disease patients Kalliopi Sofou†,a, Pashtun Shahim†, b,c, Már Tuliniusa, Kaj Blennowb,c, Henrik Zetterbergb,c,d,e, Niklas Mattssonf, Niklas Darina aDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Gothenburg, The Queen Silvia’s Children Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden bInstitute of Neuroscience and Physiology, Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry, the Sahlgrenska Academy at University of Gothenburg, Mölndal, Sweden. cClinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden dDepartment of Molecular Neuroscience, UCL Institute of Neurology, Queen Square, London, UK eUK Dementia Research Institute at UCL, London, UK fClinical Memory Research Unit, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden, and Lund University, Skåne University Hospital, Department of Clinical Sciences, Neurology, Lund, Sweden †Equal contributors Correspondence to: Kalliopi Sofou, MD, PhD Department of Pediatrics University of Gothenburg, The Queen Silvia’s Children Hospital SE-416 85 Gothenburg, Sweden Tel: +46 (0) 31 3421000 E-mail: [email protected] Abbreviations Ab42 Amyloid-b42 AD Alzheimer’s disease AUROC Area under the receiver operating-characteristic curve CNS Central nervous system CSF Cerebrospinal fluid DWI Diffusion weighted imaging FLAIR Fluid attenuated inversion recovery GFAp Glial fibrillary acidic protein KSS Kearns-Sayre syndrome LP Lumbar puncture ME Mitochondrial encephalopathy Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis and MELAS stroke-like -

Drugs for Orphan Mitochondrial Disease

Drugs for Orphan Mitochondrial Disease Gino Cortopassi, CEO Ixchel:Mayan goddess of health www.ixchelpharma.com Davis, CA Executive Summary • Ixchel is a clinical stage company focused on developing IXC-109 as therapeutic for mitochondrial diseases: 109 increases mitochondrial activities in cells & mice. • XC-109 is an NCE prodrug of the active moiety Mono-methylfumarate (MMF) upon which a Composition-of-Matter patent has been applied for. • IP: rights to 5 patent families, including composition of matter, method of use, formulation and 2 granted orphan drug designations. • Efficacy: demonstrated efficacy in preclinical mouse models with IXC-109 in Leigh’s Syndrome, Friedreich’s ataxia cardiac defects. • Patient advocacy groups & KOLs: Ixchel developed a 10-year relationship with patient advocacy groups FARA, Ataxia UK, UMDF & MDA, and networks with 8 Key Opinion Leaders in Mitochondrial Research and Mitochondrial Disease clinical development • Proven path and comps – Valuation of other MMF prodrugs: Vumerity/Alkermes 8700, Xenoport/Dr. Reddy’s – Valuation of Reata FA – IXC-109 is pharmacokinetically superior to Biogen’s DMF and Vumerity 2 Ixchel’s pipeline in orphan mitochondrial disease Benefits in Benefits in Patient Cells Target Identified Orphan Mitochondrial: Mouse models POC clinical trial Friedreich’s Ataxia, IXC103 Leigh’s Syndrome, LHON Mitochondrial Myopathy, IXC109 Duchenne’s Muscular Dystrophy 3 Defects of mitochondria are inherited and cause disease Neurodegeneration Friedreich’s ataxia Mitochondrial defect Genetics Leber’s (LHON) Myopathy Leigh Syndrome Muscle Wasting MELAS 4 Friedreich’s Ataxia as mitochondrial disease target for therapy FA as an orphan therapeutic target: § FA is the most prevalent inherited ataxia: ~6000 in North America, 15,000 Europe. -

Spinal Muscular Atrophy

Spinal Muscular Atrophy Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a genetic disorder that affects the control of muscle movement. It is caused by a loss of anterior horn cells (spinal motor neurons). Messages from the nerve cells in the brain (called upper motor neurons) are transmitted to nerve cells in the brain stem and spinal cord (called lower motor neurons) and from them to specific muscles. Upper motor neurons instruct the lower motor neurons to produce movements in the arms, legs, chest, face, throat and tongue. This loss of spinal motor neurons means that there is a lack of nerve signal from the spinal motor neurons to bunches of muscle fibres. Having no nerve signal causes these groups of muscle fibres to waste away (atrophy) which leads to weakness of muscles used for activities such as crawling, walking, sitting up, and controlling head movement. In severe cases of SMA, the muscles used for breathing and swallowing are affected. There are many types of spinal muscular atrophy distinguished by the pattern of features, severity of muscle weakness, and age when the muscle problems begin. SMA Types I – IV are different levels of severity of the same genetic defect. Xlinked spinal muscular atrophy (X-linked SMA), spinal muscular atrophy, lower extremity, dominant (SMA-LED) and adult onset spinal muscular atrophy are all caused by defects in different genes. Approximately 1 in 6,000 to 1 in 10,000 babies are born with SMA. Features of SMA Type I spinal muscular atrophy (also called Werdnig-Hoffman disease) is a severe form of the disorder that is evident at birth or within the first few months of life. -

Metabolic and Muscle-Derived Serum Biomarkers Define CHCHD10-Linked Late-Onset Spinal Muscular Atrophy

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.04.07.21254960; this version posted April 9, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Metabolic and muscle-derived serum biomarkers define CHCHD10-linked late-onset spinal muscular atrophy Julius Järvilehto, MB1, Sandra Harjuhaahto, MSc1, Edouard Palu, MD2, Mari Auranen, MD, PhD2, Jouni Kvist, PhD1, Henrik Zetterberg, MD, PhD3,4,5,6, Johanna Koskivuori, MSc7, Marko Lehtonen, PhD7, Anna Maija Saukkonen, MD8, Manu Jokela, MD, PhD9,10, Emil Ylikallio, MD, PhD1,2*, Henna Tyynismaa, PhD1,11,12* 1Stem Cells and Metabolism Research Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 2Clinical Neurosciences, Neurology, Helsinki University Hospital, Helsinki, Finland 3Clinical Neurochemistry Laboratory, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Mölndal, Sweden 4Department of Psychiatry and Neurochemistry, Institute of Neuroscience and Physiology, the Sahlgrenska Academy at the University of Gothenburg, Mölndal, Sweden 5Department of Neurodegenerative Disease, UCL Institute of Neurology, London, United Kingdom 6UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL, London, United Kingdom 7School of Pharmacy, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland 8Department of Neurology, Central Hospital of Northern Karelia, Joensuu, Finland 9Division of Clinical Neurosciences, Turku University Hospital and University of Turku, Turku, Finland 10Department of Neurology, Neuromuscular Research Center, Tampere University Hospital and Tampere University, Tampere, Finland 11Neuroscience Center, Helsinki Institute of Life Science, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 12Department of Medical and Clinical Genetics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland *Corresponding Author: Henna Tyynismaa, Biomedicum Helsinki, Haartmaninkatu 8, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. -

Mitochondrial Genome Changes and Neurodegenerative Diseases☆

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1842 (2014) 1198–1207 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biochimica et Biophysica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bbadis Review Mitochondrial genome changes and neurodegenerative diseases☆ Milena Pinto a,c,CarlosT.Moraesa,b,c,⁎ a Department of Neurology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA b Neuroscience Graduate Program, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA c Department of Cell Biology, University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, FL 33136, USA article info abstract Article history: Mitochondria are essential organelles within the cell where most of the energy production occurs by the oxida- Received 31 July 2013 tive phosphorylation system (OXPHOS). Critical components of the OXPHOS are encoded by the mitochondrial Received in revised form 6 November 2013 DNA (mtDNA) and therefore, mutations involving this genome can be deleterious to the cell. Post-mitotic tissues, Accepted 8 November 2013 such as muscle and brain, are most sensitive to mtDNA changes, due to their high energy requirements and non- Available online 16 November 2013 proliferative status. It has been proposed that mtDNA biological features and location make it vulnerable to mu- tations, which accumulate over time. However, although the role of mtDNA damage has been conclusively con- Keywords: Mitochondrion nected to neuronal impairment in mitochondrial diseases, its role in age-related neurodegenerative diseases mtDNA remains speculative. Here we review the pathophysiology of mtDNA mutations leading to neurodegeneration Encephalopathy and discuss the insights obtained by studying mouse models of mtDNA dysfunction.