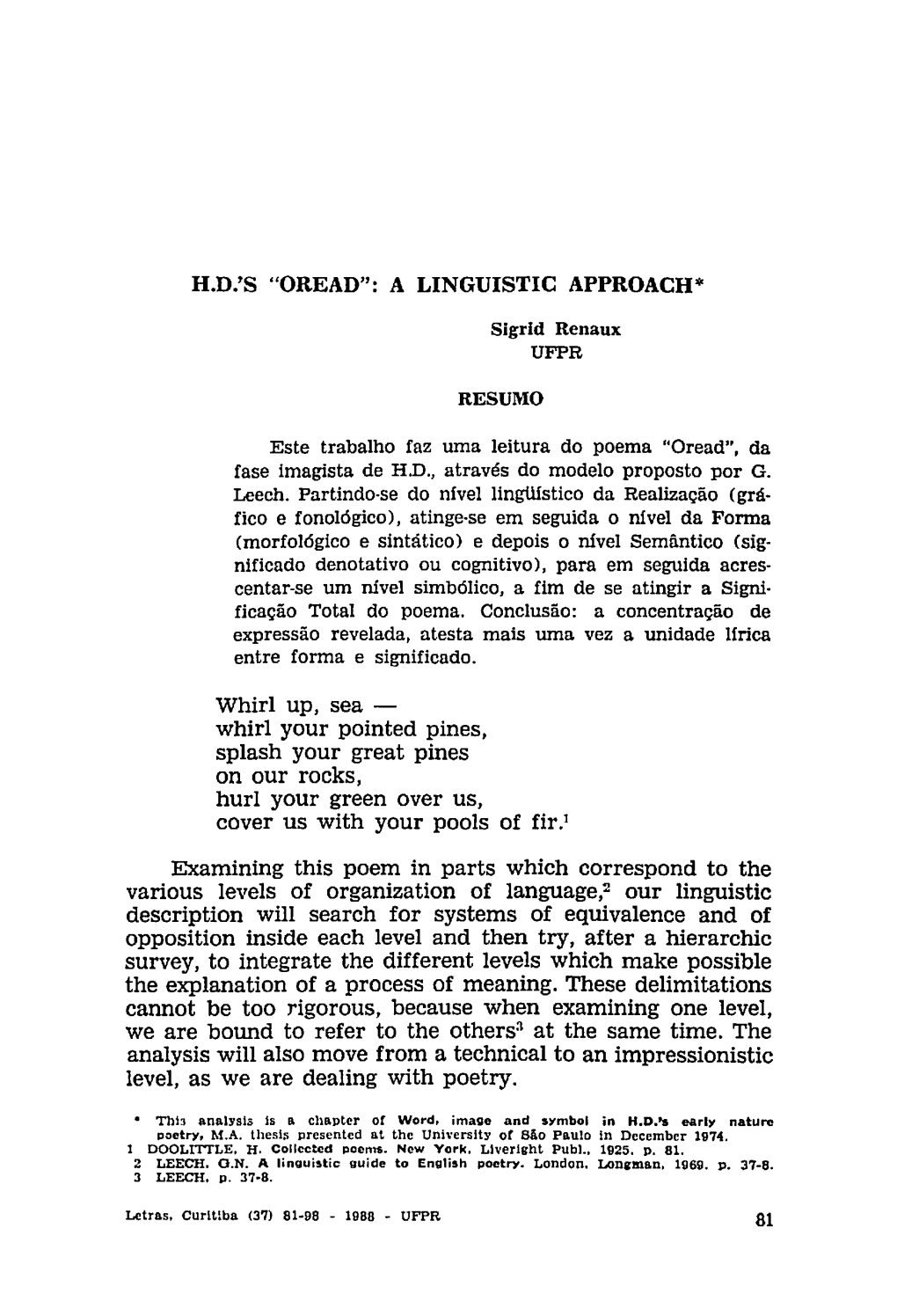

Oread": a Linguistic Approach*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Visual Aid: Teaching H.D.'S Imagist Poetry with the Assistance Of

Teaching American Literature: A Journal of Theory and Practice Winter 2008 (2:1) Visual Aid: Teaching H.D.'s Imagist Poetry with the Assistance of Henri Matisse Christa Baiada, Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY The mantra of the modernist movement, articulated by Ezra Pound, was "make it new." Unfortunately, students don't always know how to approach "new" styles of literature, especially poetry that itself daunts many students. As we've all observed, if not experienced for ourselves, modernist poetry, upon first encounter, can be especially intimidating. In the spirit of making it new, this poetry often appears obscure in its density, perspective, and complexity. Students may look at a poem like "The Red Wheel Barrow" and ask "how is this poetry?" Of course, this is precisely the question we want to work through with them, so this is good. On the other hand, the initial discomfort of students with modernism can develop into a resistance hard to tackle. This is a challenge I found especially difficult to address in my early attempts to teach the poems of H.D. at a small, suburban music college in Long Island, NY. For my first lesson at the start of a unit on modernism in an undergraduate 200-level, Introduction to Literature class, I would devote the entire period to H.D. because I believe that her work beautifully encapsulates many of the principles of modernism laid out by Pound in his seminal essay "A Retrospect." Though several of my students have been fans, or even writers, of poetry and most had artistic sensibilities, many were disconcerted in their first encounter with modernist poetry via H.D., and the malaise they felt would linger in the following weeks as we read additional modernist poets. -

H.D., Daughter of Helen: Mythology As Actuality

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Classical Studies) Classical Studies at Penn 2009 H.D., Daughter of Helen: Mythology as Actuality Sheila Murnaghan University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers Part of the Classics Commons Recommended Citation (OVERRIDE) Murnaghan, Sheila. “H.D., Daughter of Helen: Mythology as Actuality,” in Gregory A. Staley, ed., American Women and Classical Myths, Waco: Baylor University Press, 2009: 63-84. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/84 For more information, please contact [email protected]. H.D., Daughter of Helen: Mythology as Actuality Abstract For H.D., classical mythology was an essential means of expression, first acquired in childhood and repossessed throughout her life. H.D.’s extensive output of poems, memoirs, and novels is marked by a pervasive Hellenism which evolved in response to the changing conditions of her life and art, but remained her constant idiom. She saw herself as reliving myth, and she used myth as a medium through which to order her own experience and to rethink inherited ideas. If myth served H.D. as a resource for self-understanding and artistic expression, H.D. herself has served subsequent poets, critics, and scholars as a model for the writer’s ability to reclaim myth, to create something new and personal out of ancient shared traditions. Disciplines Arts and Humanities | Classics This book chapter is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/classics_papers/84 Gregory A. Staley, editor, American Women and Classical Myths (Waco, Tex.: Baylor University Press, 2009) © Baylor University Press. -

Catharsis Discussion Circle, We Have Prepared This List of Frequently Asked Questions to Assist Participants with Common Concerns

Frequently Asked Questions Thank you for your help in this important research project! In order to facilitate a successful Catharsis discussion circle, we have prepared this list of Frequently Asked Questions to assist participants with common concerns. Q: Do I need to make any special preparations before the session? A: No, you can follow your normal routine. There is no need to avoid food or drink before the session. Q: Is there any physical discomfort associated with channeling? A: No. However, as you may be sitting for long periods, we recommend taking breaks to stand and stretch from time to time. Q: Will I get to pick which entity I am channeling? A: Yes, with some limitations. Hera is always present in a Catharsis session. If the person channeling her leaves the group or chooses another entity to channel, she will "jump" to another random person; if that person is already channeling, the entity already present will be expelled, either to withdraw or to find another willing channeler. Q: What if I arrive at the session late? A: Catharsis sessions are designed to be unstructured and participant-led, so it's fine if you don't arrive at the same time as everyone else. We recommend that before joining in the conversation, you take a few minutes to consider personality of the entity you have decided to channel, and their relation to the others present. Then, just relax and allow them to speak through you. Q: What if I need to leave early? A: No problem! Simply relax and wait a moment for the entity you are channeling to separate from you, then quietly leave the circle. -

Circe's Understanding of Rape Victims in Ovid's Metamorphoses

New England Classical Journal Volume 43 Issue 4 Pages 203-240 11-2016 Circe’s Understanding of Rape Victims in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, XIV Karen Mower Rufo Waltham High School Follow this and additional works at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj Recommended Citation Rufo, Karen Mower (2016) "Circe’s Understanding of Rape Victims in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, XIV," New England Classical Journal: Vol. 43 : Iss. 4 , 203-240. Available at: https://crossworks.holycross.edu/necj/vol43/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CrossWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in New England Classical Journal by an authorized editor of CrossWorks. ARTICLES AND NOTES New England Classical Journal 43.4 (2016) 203-240 Circe’s Understanding of Rape Victims in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, XIV Karen Mower Rufo Waltham High School e f I. INTRODUCTION: PREDATOR AS READER1 Violence in idyllic settings crafts a type of informal “education” by which characters of Ovid’s Metamorphoses learn from previous stories how to (re)act and how to un- derstand their situations and roles within the narrative. The goddess Circe receives such an education from successful and unsuccessful rapes committed by divine or semi-divine beings on others who travel in idyllic scenery. In this paper I argue that Circe exploits this understanding in order to make her attempt on Picus, thus “reading” the Metamorphoses to achieve her victory over and metamorphical rape of her love-prey. The idea of a female character reacting to the narrative based on her “under- standing” of previous stories in the Metamorphoses originates in the work of John Heath. -

Bulfinch's Mythology

Bulfinch's Mythology Thomas Bulfinch Bulfinch's Mythology Table of Contents Bulfinch's Mythology..........................................................................................................................................1 Thomas Bulfinch......................................................................................................................................1 PUBLISHERS' PREFACE......................................................................................................................3 AUTHOR'S PREFACE...........................................................................................................................4 STORIES OF GODS AND HEROES..................................................................................................................7 CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................7 CHAPTER II. PROMETHEUS AND PANDORA...............................................................................13 CHAPTER III. APOLLO AND DAPHNEPYRAMUS AND THISBE CEPHALUS AND PROCRIS7 CHAPTER IV. JUNO AND HER RIVALS, IO AND CALLISTODIANA AND ACTAEONLATONA2 AND THE RUSTICS CHAPTER V. PHAETON.....................................................................................................................27 CHAPTER VI. MIDASBAUCIS AND PHILEMON........................................................................31 CHAPTER VII. PROSERPINEGLAUCUS AND SCYLLA............................................................34 -

For a Falcon

New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves CRESCENT BOOKS NEW YORK New Larousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Translated by Richard Aldington and Delano Ames and revised by a panel of editorial advisers from the Larousse Mvthologie Generate edited by Felix Guirand and first published in France by Auge, Gillon, Hollier-Larousse, Moreau et Cie, the Librairie Larousse, Paris This 1987 edition published by Crescent Books, distributed by: Crown Publishers, Inc., 225 Park Avenue South New York, New York 10003 Copyright 1959 The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited New edition 1968 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the permission of The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. ISBN 0-517-00404-6 Printed in Yugoslavia Scan begun 20 November 2001 Ended (at this point Goddess knows when) LaRousse Encyclopedia of Mythology Introduction by Robert Graves Perseus and Medusa With Athene's assistance, the hero has just slain the Gorgon Medusa with a bronze harpe, or curved sword given him by Hermes and now, seated on the back of Pegasus who has just sprung from her bleeding neck and holding her decapitated head in his right hand, he turns watch her two sisters who are persuing him in fury. Beneath him kneels the headless body of the Gorgon with her arms and golden wings outstretched. From her neck emerges Chrysor, father of the monster Geryon. Perseus later presented the Gorgon's head to Athene who placed it on Her shield. -

A Computational Analysis of Poetic Style: Imagism and Its Influence On

LiLT volume12,issue3 October2015 A computational analysis of poetic style Imagism and its influence on modern professional and amateur poetry Justine T. Kao, Department of Psychology, Stanford University, [email protected] Dan Jurafsky, Department of Linguistics, Stanford University, [email protected] Abstract How do standards of poetic beauty change as a function of time and expertise? Here we use computational methods to compare the stylistic features of 359 English poems written by 19th century professional po- ets, Imagist poets, contemporary professional poets, and contemporary amateur poets. Building upon techniques designed to analyze style and sentiment in texts, we examine elements of poetic craft such as imagery, sound devices, emotive language, and diction. We find that contempo- rary professional poets use significantly more concrete words than 19th century poets, fewer emotional words, and more complex sound devices. These changes are consistent with the tenets of Imagism, an early 20th- century literary movement. Further analyses show that contemporary amateur poems resemble 19th century professional poems more than contemporary professional poems on several dimensions. The stylistic similarities between contemporary amateur poems and 19th century professional poems suggest that elite standards of poetic beauty in the past “trickled down” to influence amateur works in the present. Our LiLT Volume 12, Issue 3, October 2015. A computational analysis of poetic style. Copyright c 2015, CSLI Publications. 1 2/LiLT volume12,issue3 October2015 results highlight the influence of Imagism on the modern aesthetic and reveal the dynamics between “high” and “low” art. We suggest that computational linguistics may shed light on the forces and trends that shape poetic style. -

Power of the Gods

Power of the Gods By Jeffrey Smart Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Call the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The authors’ name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Company.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY www.histage.com © 1997 by Jeffrey Smart Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing http://www.histage.com/playdetails.asp?PID=121 Power of the Gods -2- STORY OF THE PLAY Ashley, a novice dryad, or tree sprite, makes her first visit to Mt. Olympus to meet the powerful pantheon of gods and goddesses of Ancient Greece. She is overwhelmed by the way the Great Olympians live and the power that they wield, and wants to grab a little of the glory for herself. She becomes friends with Persephone, the maiden of spring, who is running away from her brooding husband, Hades. Together the women set off on an ambitious odyssey to steal Zeus’ lightning bolts, Poseidon’s trident, and Hades’ helmet of invisibility and take over Mt. Olympus! They are pursued by the vengeful goddess, Hera, and eventually learn an important lesson about the balance of power. Power of the Gods -3- CAST OF CHARACTERS (4 m, 6 w, many extras) OLYMPIANS ARTEMIS: A goddess of three forms: the hunt (Artemis); the moon (Selene) and of mystery (Hecate). ASHLEY: A dryad. -

A Sorcerous Origin

Contents Foreword.............................................................................. 1 Sorcerer ...............................................................................2 Sorcerous Origin ..............................................................2 Nymph Bloodline ..........................................................2 Sidebars Supernatural Marks ........................................................3 Nymph Bloodlines on Other Worlds .......................4 Nymph Bloodline Sorcerers and Devotion 5............ Nymph Bloodline A Sorcerous Origin By Christopher M. Cevasco Foreword The Player's Handbook, Xanathar's Guide to Art Credits Everything, and the Sword Coast Adventurer's ON THE COVER: Altered version of An Egyptian at His Guide offer several distinct subclass options Doorway in Memphis by Dutch artist Lawrence Alma- for sorcerers—mystic origins that transform an Tadema (1836 - 1912). individual so as to unlock arcane methods of accessing the magical Weave and allow for Border pattern around sidebar boxes adapted from a design by Gordon Johnson from Pixabay. sorcerous spellcasting. This supplement offers a new sorcerous Apart from those images obtained through DMs Guild origin with strong ties to the world presented in Creator Resource artpacks, all other illustrations herein Mythic Odysseys of Theros. Nymph Bloodline are in the public domain or alterations thereof. sorcerers have been transformed by a nymph page backgrounds are from Cole Twogood's old paper heritage that's been mingled with their own or -

Klasik Yunan Mitolojisi

KLASİK YUNAN MİTOLOJİSİ Şefik Can YAYIN NU: 896 KÜLTÜR SERİSİ: 470 T.C. KÜLTÜR ve TURİZM BAKANLIĞI SERTİFİKA NUMARASI: 16267 ISBN: 978-975-437-858-0 www.otuken.com.tr [email protected] 1.-9. BASIM: 1970-2009 İnkılâp 10. Basım: 2011, Ötüken 19. BASIM ÖTÜKEN NEŞRİYAT A.Ş.® İstiklâl Cad. Ankara Han 65/3 • 34433 Beyoğlu-İstanbul Tel: (0212) 251 03 50 • (0212) 293 88 71 - Faks: (0212) 251 00 12 Kapak Tasarımı: Zafer Yılmaz Dizgi-Tertip: Ötüken Kapak Baskısı: Pelikan Basım Baskı: İmak Ofset Basım Yayın San. ve Tic. Ltd. Şti. Sertifika Numarası: 45523 Tel: (0212) 444 62 18 İstanbul- 20 Kitabın bütün yayın hakları Ötüken Neşriyat A.Ş.’ye aittir. Yayınevinden yazılı izin alınmadan, kaynağın açıkça belirtildiği akademik çalışmalar ve tanıtım faaliyetleri haricinde, kısmen veya tamamen alıntı 20 yapılamaz; hiçbir matbu ve dijital ortamda kopya edilemez, çoğaltılamaz ve yayımlanamaz. İÇİNDEKİLER Önsöz............................................................................................................................................ 9 Birinci Basımın Önsözü .............................................................................................................. 17 Mitoloji ........................................................................................................................................ 17 Mitler Nasıl Doğar? ................................................................................................................ 18 Yunan Theogonisi ..............................................................................................................................21 -

Greco: Roman Mythology

Greco: Roman Mythology Greco-RomanEncyclopedia of Mythology Mike Dixon-Kennedy B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 1998 by Mike Dixon-Kennedy All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or trans- mitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dixon-Kennedy, Mike, 1958– Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman mythology / Mike Dixon-Kennedy. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Mythology, Classical—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BL715.D56 1998 292.1'3'03—dc21 98-40666 CIP ISBN 1-57607-094-8 (hc) ISBN 1-57607-129-4 (pbk) 0403020100999810987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 Typesetting by Letra Libre This book is printed on acid-free paper I . Manufactured in the United States of America. For my father, who first told me stories from ancient Greece and Rome K Contents k Preface, ix How to Use This Book, xi Greece and Greek Civilization, xiii Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology, 1 Bibliography, 331 Appendix 1: Chronologies for Ancient Greece and Rome, 341 Appendix 2: Roman Emperors, 343 Index, 345 vii K Preface k Perhaps more words have been written, and now contains a mass of information about over a longer period of time, about the classi- each and every world culture, from the Aztecs cal Greek and Roman cultures than any other. -

Look Out, Olympus!

LOOK OUT, OLYMPUS! A Musical in Two Acts Book by Jeffrey Smart Music and Lyrics by Scott Keys Performance Rights It is an infringement of the federal copyright law to copy or reproduce this script in any manner or to perform this play without royalty payment. All rights are controlled by Eldridge Publishing Co., Inc. Call the publisher for additional scripts and further licensing information. The authors’ name must appear on all programs and advertising with the notice: “Produced by special arrangement with Eldridge Publishing Co.” PUBLISHED BY ELDRIDGE PUBLISHING COMPANY www.histage.com © 1997 by Jeffrey Smart and Eldridge Publishing Download your complete script from Eldridge Publishing https://histage.com/look-out-olympus LOOK OUT, OLYMPUS! 2 STORY OF THE PLAY Here’s a musical of mythical proportions! Ashley, a novice dryad,or tree sprite, makes her first visit to Mt. Olympus to meet the powerful pantheon of gods and goddesses of Ancient Greece. She is overwhelmed by the way the Great Olympians live and the power that they wield, and wants to grab a little of the glory for herself. She becomes friends with Persephone, the maiden of spring, who is running away from her brooding husband, Hades. Together the women set off on an ambitious odyssey to steal Zeus’ lightning bolts, Poseidon’s trident, and Hades’ helmet of invisibility and take over Mt. Olympus! They are pursued by the vengeful goddess, Hera, and eventually learn an important lesson about the balance of power. LOOK OUT, OLYMPUS! 3 CAST OF CHARACTERS (4 m, 6 w, extras) ARTEMIS: A goddess of three forms: the hunt (Artemis); the moon (Selene) and of mystery (Hecate).