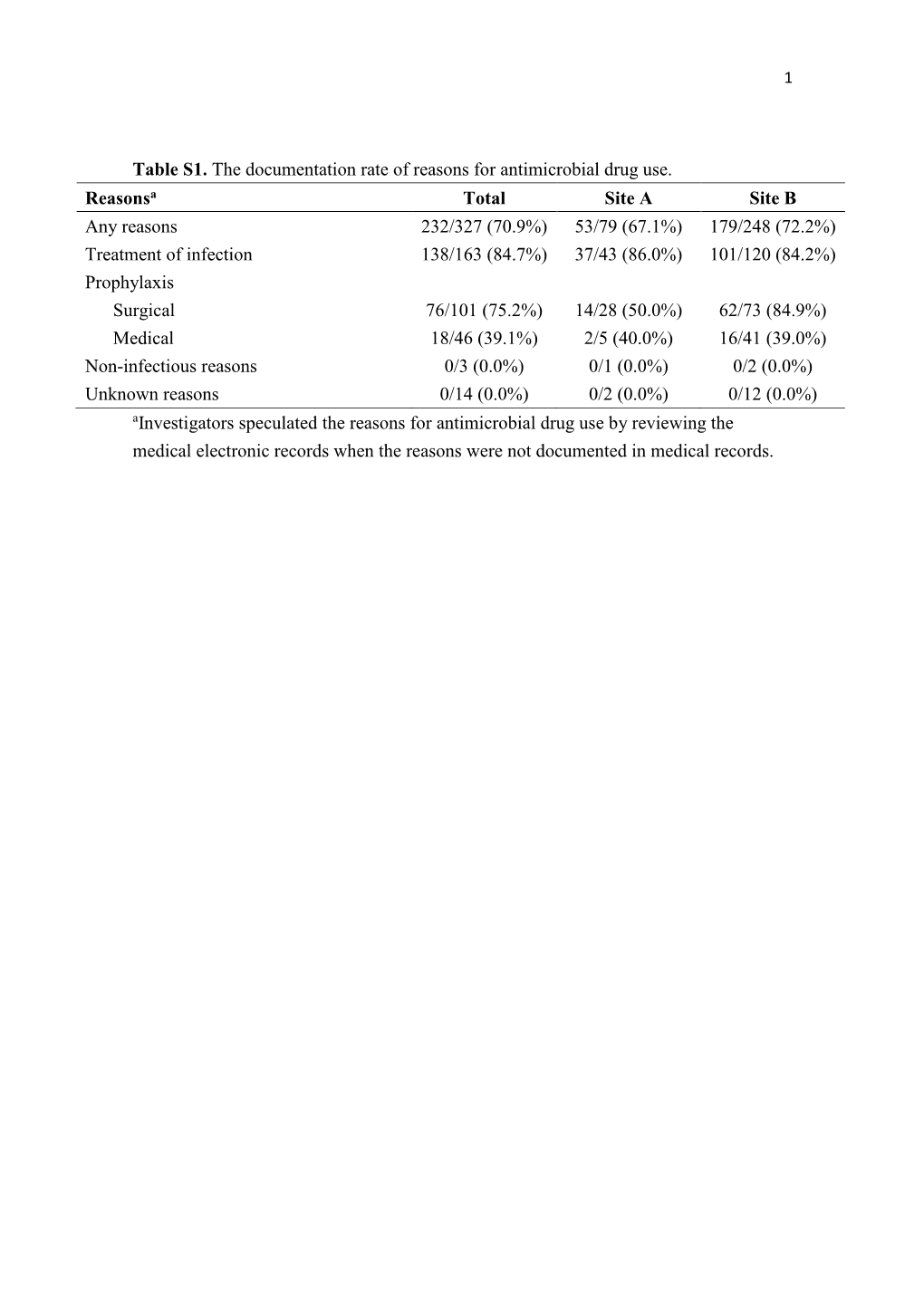

Table S1. the Documentation Rate of Reasons for Antimicrobial Drug Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ecology of Staphylococcus Species in the Oral Cavity

J. Med. Microbiol. Ð Vol. 50 2001), 940±946 # 2001 The Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland ISSN 0022-2615 REVIEW ARTICLE The ecology of Staphylococcus species in the oral cavity A. J. SMITH, M. S. JACKSON and J. BAGG Infection Research Group, Glasgow Dental Hospital and School, 378 Sauchiehall Street, Glasgow G2 3JZ Whilst the diversity of organisms present in the oral cavity is well accepted, there remains considerable controversy as to whether Staphylococcus spp. play a role in the ecology of the normal oral ¯ora. Surprisingly little detailed work has been performed on the quantitative and qualitative aspects of colonisation or infection either by coagulase- negative staphylococci CNS) or S. aureus. The latter is especially interesting in the light of present dif®culties in eradicating carriage of methicillin-resistant S. aureus MRSA) from the oropharynx in affected individuals. This paper reviews the current knowledge of staphylococcal colonisation and infection of the oral cavity in health and disease. S. aureus has been isolated from a wide range of infective oral conditions, such as angular cheilitis and parotitis. More recently, a clinical condition classi®ed as staphylococcal mucositis has emerged as a clinical problem in many debilitated elderly patients and those with oral Crohn's disease. Higher carriage rates of both CNS or S. aureus,or both, in patients prone to joint infections raises the interesting possibility of the oral cavity serving as a potential source for bacteraemic spread to compromised joint spaces. In conclusion, there is a surprising paucity of knowledge regarding the role of oral staphylococci in both health and disease. -

The C-Di-Gmp Regulatory Network in Clostridioides Difficile and Its Role in Modulating Surface Adherence and Persistence in the Mammalian Gut

THE C-DI-GMP REGULATORY NETWORK IN CLOSTRIDIOIDES DIFFICILE AND ITS ROLE IN MODULATING SURFACE ADHERENCE AND PERSISTENCE IN THE MAMMALIAN GUT Robert Woodrow McKee A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology. Chapel Hill 2018 Approved by: Peggy A Cotter Jonathan J. Hansen Virginia L. Miller Rita Tamayo Mathew C Wolfgang © 2018 Robert Woodrow McKee ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Robert Woodrow McKee: The c-di-GMP regulatory network in Clostridioides difficile and its role in modulating surface adherence and persistence in the mammalian gut (Under the direction of Rita Tamayo) Clostridioides difficile (Clostridium difficile) is a spore-forming bacterial pathogen responsible for hundreds of thousands of infections each year in the United States. C. difficile outbreaks are common in hospitals because C. difficile spores can persist for months on surfaces and are resistant to many disinfectants. Despite the significant disease burden that C. difficile represents, we know surprisingly little about the factors necessary for C. difficile to colonize and persist in the mammalian intestine. Previous work demonstrated that the signaling molecule cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates a variety of processes in C. difficile including production of the toxins that are required for disease symptoms. Using monolayers of human intestinal epithelial cells, we demonstrate that c-di-GMP promotes attachment of C. difficile to intestinal epithelial cells. We also demonstrate that regulation of type IV pili (TFP) by c-di-GMP promotes prolonged adherence of C. -

Common Commensals

Common Commensals Actinobacterium meyeri Aerococcus urinaeequi Arthrobacter nicotinovorans Actinomyces Aerococcus urinaehominis Arthrobacter nitroguajacolicus Actinomyces bernardiae Aerococcus viridans Arthrobacter oryzae Actinomyces bovis Alpha‐hemolytic Streptococcus, not S pneumoniae Arthrobacter oxydans Actinomyces cardiffensis Arachnia propionica Arthrobacter pascens Actinomyces dentalis Arcanobacterium Arthrobacter polychromogenes Actinomyces dentocariosus Arcanobacterium bernardiae Arthrobacter protophormiae Actinomyces DO8 Arcanobacterium haemolyticum Arthrobacter psychrolactophilus Actinomyces europaeus Arcanobacterium pluranimalium Arthrobacter psychrophenolicus Actinomyces funkei Arcanobacterium pyogenes Arthrobacter ramosus Actinomyces georgiae Arthrobacter Arthrobacter rhombi Actinomyces gerencseriae Arthrobacter agilis Arthrobacter roseus Actinomyces gerenseriae Arthrobacter albus Arthrobacter russicus Actinomyces graevenitzii Arthrobacter arilaitensis Arthrobacter scleromae Actinomyces hongkongensis Arthrobacter astrocyaneus Arthrobacter sulfonivorans Actinomyces israelii Arthrobacter atrocyaneus Arthrobacter sulfureus Actinomyces israelii serotype II Arthrobacter aurescens Arthrobacter uratoxydans Actinomyces meyeri Arthrobacter bergerei Arthrobacter ureafaciens Actinomyces naeslundii Arthrobacter chlorophenolicus Arthrobacter variabilis Actinomyces nasicola Arthrobacter citreus Arthrobacter viscosus Actinomyces neuii Arthrobacter creatinolyticus Arthrobacter woluwensis Actinomyces odontolyticus Arthrobacter crystallopoietes -

A Prospective Role for the Rumen in Generating Antibiotic Resistance 2 3 Cameron R

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/729681; this version posted August 12, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 TITLE: A prospective role for the rumen in generating antibiotic resistance 2 3 Cameron R. Strachan1,4,*, Anna J. Mueller2, Mahdi Ghanbari3, Viktoria Neubauer4, Benjamin 4 Zwirzitz1,4, Sarah Thalguter1,4, Monika Dziecol4, Stefanie U. Wetzels4, Jürgen Zanghellini5,6,7, 5 Martin Wagner1, 4, Stephan Schmitz-Esser8, Evelyne Mann4 6 7 1FFoQSI GmbH, Technopark 1C, 3430 Tulln, Austria 8 2University of Vienna, Centre for Microbiology and Environmental Systems Science, 9 Division of Microbial Ecology, Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria 10 11 3BIOMIN Research Center, Technopark 1, 3430, Tulln, Austria 12 13 4Institute of Food Safety, Food Technology and Veterinary Public Health, Department for Farm 14 Animals and Public Health, University of Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Veterinärplatz 1, 1210 15 Vienna, Austria 16 17 5Austrian Centre of Industrial Biotechnology, 1190 Vienna, Austria 18 19 6Department of Biotechnology, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences, Vienna, 1190 20 Vienna, Austria 21 22 7Austrian Biotech University of Applied Sciences, 3430 Tulln, Austria 23 24 8Department of Animal Science, Iowa State University, 3222 National Swine Research and 25 Information Center, 1029 North University Blvd, Ames, IA 50011-3611, USA. 26 27 *Author correspondence: [email protected] 28 29 ABSTRACT 30 31 Antibiotics were a revolutionary discovery of the 20th century, but the ability of bacteria to 32 spread the genetic determinants of resistance via horizontal gene transfer (HGT) has quickly 33 endangered their use1. -

Identification of Clinically Relevant Streptococcus and Enterococcus

pathogens Article Identification of Clinically Relevant Streptococcus and Enterococcus Species Based on Biochemical Methods and 16S rRNA, sodA, tuf, rpoB, and recA Gene Sequencing Maja Kosecka-Strojek 1,* , Mariola Wolska 1, Dorota Zabicka˙ 2 , Ewa Sadowy 3 and Jacek Mi˛edzobrodzki 1 1 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Biochemistry, Biophysics and Biotechnology, Jagiellonian University, 30-387 Krakow, Poland; [email protected] (M.W.); [email protected] (J.M.) 2 Department of Molecular Microbiology, National Medicines Institute, 00-725 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] 3 Department of Epidemiology and Clinical Microbiology, National Medicines Institute, 00-725 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +48-12-664-6365 Received: 13 October 2020; Accepted: 9 November 2020; Published: 11 November 2020 Abstract: Streptococci and enterococci are significant opportunistic pathogens in epidemiology and infectious medicine. High genetic and taxonomic similarities and several reclassifications within genera are the most challenging in species identification. The aim of this study was to identify Streptococcus and Enterococcus species using genetic and phenotypic methods and to determine the most discriminatory identification method. Thirty strains recovered from clinical samples representing 15 streptococcal species, five enterococcal species, and four nonstreptococcal species were subjected to bacterial identification by the Vitek® 2 system and Sanger-based sequencing methods targeting the 16S rRNA, sodA, tuf, rpoB, and recA genes. Phenotypic methods allowed the identification of 10 streptococcal strains, five enterococcal strains, and four nonstreptococcal strains (Leuconostoc, Granulicatella, and Globicatella genera). The combination of sequencing methods allowed the identification of 21 streptococcal strains, five enterococcal strains, and four nonstreptococcal strains. -

Incidence of Bacteriocins Produced by Food-Related Lactic Acid Bacteria Active Towards Oral Pathogens

Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 4640-4654; doi:10.3390/ijms14034640 OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Molecular Sciences ISSN 1422-0067 www.mdpi.com/journal/ijms Article Incidence of Bacteriocins Produced by Food-Related Lactic Acid Bacteria Active towards Oral Pathogens Georgia Zoumpopoulou 1, Eudoxie Pepelassi 2, William Papaioannou 3, Marina Georgalaki 1, Petros A. Maragkoudakis 1,†, Petros A. Tarantilis 4, Moschos Polissiou 4, Effie Tsakalidou 1 and Konstantinos Papadimitriou 1,* 1 Laboratory of Dairy Research, Department of Food Science and Technology, Agricultural University of Athens, Iera Odos 75, Athens 11855, Greece; E-Mails: [email protected] (G.Z.); [email protected] (M.G.); [email protected] (P.A.M.); [email protected] (E.T.) 2 Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 2 Thivon Str., Athens 11527, Greece; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Preventive and Community Dentistry, School of Dentistry, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 2 Thivon Str., Athens 11527, Greece; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 Laboratory of Chemistry, Department of Science, Agricultural University of Athens, Iera Odos 75, Athens 11855, Greece; E-Mails: [email protected] (P.A.T.); [email protected] (M.P.) † Present address: European Commission, Joint Research Centre, via E. Fermi 2749, Ispra 21027, Varese, Italy; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +30-210-529-4661; Fax: +30-210-529-4672. Received: 8 October 2012; in revised form: 1 February 2013 / Accepted: 18 February 2013 / Published: 26 February 2013 Abstract: In the present study we investigated the incidence of bacteriocins produced by 236 lactic acid bacteria (LAB) food isolates against pathogenic or opportunistic pathogenic oral bacteria. -

Probiotics Streptococcus Salivarius 24SMB And

Bidossi et al. BMC Infectious Diseases (2018) 18:653 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3576-9 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Probiotics Streptococcus salivarius 24SMB and Streptococcus oralis 89a interfere with biofilm formation of pathogens of the upper respiratory tract Alessandro Bidossi1, Roberta De Grandi1, Marco Toscano2, Marta Bottagisio1, Elena De Vecchi1, Matteo Gelardi3 and Lorenzo Drago1,2* Abstract Background: Infections of the ears, paranasal sinuses, nose and throat are very common and represent a serious issue for the healthcare system. Bacterial biofilms have been linked to upper respiratory tract infections and antibiotic resistance, raising serious concerns regarding the therapeutic management of such infections. In this context, novel strategies able to fight biofilms may be therapeutically beneficial and offer a valid alternative to conventional antimicrobials. Biofilms consist of mixed microbial communities, which interact with other species in the surroundings and communicate through signaling molecules. These interactions may result in antagonistic effects, which can be exploited in the fight against infections in a sort of “bacteria therapy”. Streptococcus salivarius and Streptococcus oralis are α-hemolytic streptococci isolated from the human pharynx of healthy individuals. Several studies on otitis-prone children demonstrated that their intranasal administration is safe and well tolerated and is able to reduce the risk of acute otitis media. The aim of this research is to assess S. salivarius 24SMB and S. oralis 89a for the ability to interfere with biofilm of typical upper respiratory tract pathogens. Methods: To investigate if soluble substances secreted by the two streptococci could inhibit biofilm development of the selected pathogenic strains, co-cultures were performed with the use of transwell inserts. -

Aerobic Gram-Positive Bacteria

Aerobic Gram-Positive Bacteria Abiotrophia defectiva Corynebacterium xerosisB Micrococcus lylaeB Staphylococcus warneri Aerococcus sanguinicolaB Dermabacter hominisB Pediococcus acidilactici Staphylococcus xylosusB Aerococcus urinaeB Dermacoccus nishinomiyaensisB Pediococcus pentosaceusB Streptococcus agalactiae Aerococcus viridans Enterococcus avium Rothia dentocariosaB Streptococcus anginosus Alloiococcus otitisB Enterococcus casseliflavus Rothia mucilaginosa Streptococcus canisB Arthrobacter cumminsiiB Enterococcus durans Rothia aeriaB Streptococcus equiB Brevibacterium caseiB Enterococcus faecalis Staphylococcus auricularisB Streptococcus constellatus Corynebacterium accolensB Enterococcus faecium Staphylococcus aureus Streptococcus dysgalactiaeB Corynebacterium afermentans groupB Enterococcus gallinarum Staphylococcus capitis Streptococcus dysgalactiae ssp dysgalactiaeV Corynebacterium amycolatumB Enterococcus hiraeB Staphylococcus capraeB Streptococcus dysgalactiae spp equisimilisV Corynebacterium aurimucosum groupB Enterococcus mundtiiB Staphylococcus carnosusB Streptococcus gallolyticus ssp gallolyticusV Corynebacterium bovisB Enterococcus raffinosusB Staphylococcus cohniiB Streptococcus gallolyticusB Corynebacterium coyleaeB Facklamia hominisB Staphylococcus cohnii ssp cohniiV Streptococcus gordoniiB Corynebacterium diphtheriaeB Gardnerella vaginalis Staphylococcus cohnii ssp urealyticusV Streptococcus infantarius ssp coli (Str.lutetiensis)V Corynebacterium freneyiB Gemella haemolysans Staphylococcus delphiniB Streptococcus infantarius -

HIGHLIGHTS of PRESCRIBING INFORMATION These Highlights Do

HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION • Dosage in Pediatric Patients (1 Month of Age to 16 Years): 20 to 40 These highlights do not include all the information needed to use mg/kg/day in 3 or 4 equal doses by intravenous infusion. (2.3) • Alternative Pediatric Patients Dosing: 350 mg/m2/day for serious CLINDAMYCIN IN 0.9% SODIUM CHLORIDE injection safely and 2 effectively. See full prescribing information for CLINDAMYCIN IN infections and 450 mg/m /day for more severe infections. (2.3) 0.9% SODIUM CHLORIDE injection. • Dosage in Neonates (Less than 1 Month of Age): 15 to 20 mg/kg/day in 3 to 4 equal doses by intravenous infusion. (2.3) CLINDAMYCIN IN 0.9% SODIUM CHLORIDE injection, for --------------------- DOSAGE FORMS AND STRENGTHS --------------------- intravenous use Each 50 mL of Clindamycin in 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection, Initial U.S. Approval: 1989 300 mg/50 mL (6 mg/mL), 600 mg/50 mL (12 mg/mL), and 900 mg/50 mL (18 mg/mL) contains 300 mg, 600 mg, or 900 mg clindamycin, respectively WARNING: CLOSTRIDIOIDES DIFFICILE-ASSOCIATED (as clindamycin phosphate, USP), in a single-dose GALAXY container. (3) DIARRHEA (CDAD) and COLITIS ------------------------------ CONTRAINDICATIONS ----------------------------- See full prescribing information for complete boxed warning. Individuals with a history of hypersensitivity to preparations containing clindamycin or lincomycin. (4) Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) has been reported with use of nearly all antibacterial agents, including Clindamycin in ----------------------- WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ----------------------- 0.9% Sodium Chloride Injection and may range in severity from mild • Anaphylactic shock and anaphylactic reactions have been reported. (5.2) diarrhea to fatal colitis. -

Lipoteichoic Acid of Streptococcus Oralis

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Lipoteichoic acid of Streptococcus oralis Uo5: a novel biochemical structure comprising an unusual Received: 03 June 2015 Accepted: 14 October 2015 phosphorylcholine substitution Published: 18 November 2015 pattern compared to Streptococcus pneumoniae Nicolas Gisch1, Dominik Schwudke1, Simone Thomsen1, Nathalie Heß2, Regine Hakenbeck2 & Dalia Denapaite2 Members of the Mitis group of streptococci possess teichoic acids (TAs) as integral components of their cell wall that are unique among Gram-positive bacteria. Both, lipoteichoic (LTA) and wall teichoic acid, are formed by the same biosynthetic pathway, are of high complexity and contain phosphorylcholine (P-Cho) residues. These residues serve as anchors for choline-binding proteins (CBPs), some of which have been identified as virulence factors of the human pathogen Streptococcus pneumoniae. We investigated the LTA structure of its close relative Streptococcus oralis. Our analysis revealed that S. oralis Uo5 LTA has an overall architecture similar to pneumococcal LTA (pnLTA) and can be considered as a subtype of type IV LTA. Its structural complexity is even higher than that of pnLTA and its composition differs in number and type of carbohydrate moieties, inter-residue connectivities and especially the P-Cho substitution pattern. Here, we report the occurrence of a saccharide moiety substituted with two P-Cho residues, which is unique as yet in bacterial derived surface carbohydrates. Finally, we could link the observed important structural variations between S. oralis and S. pneumoniae LTA to the divergent enzymatic repertoire for their TA biosynthesis. Peptidoglycan, wall teichoic acids (WTA) and lipoteichoic acids (LTA) are the major polysaccharides of the Gram-positive cell wall. -

Effects of Oral Streptococci and Selected Probiotic Bacteria on the Pathogen Streptococcus Pyogenes: Viability, Biofilms, Molecular Functions, and Virulence Traits

Effects of oral streptococci and selected probiotic bacteria on the pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes: viability, biofilms, molecular functions, and virulence traits Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum naturalium (Dr. rer. nat) der Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Univesität Rostock vorgelegt von Catur Riani geb. am 13.08.1976 auf Pulau Sambu aus Indonesien Rostock, Januar 2009 urn:nbn:de:gbv:28-diss2009-0087-1 Prof. Johannes Knobloch (Gutachter / Reviewer) Universitätsklinikum Schleswig-Holstein Campus Lübeck Ratzeburger Allee 160 23538 Lübeck Prof. Dr. Hubert Bahl (Gutachter / Reviewer) Uni Rostock Institut für Biologie Albert Einstein Str. 3 18059 Rostock Prof. Dr. Regine Hakenbeck (Gutachter / Reviewer) Technische Universität Kaiserslautern FB Biologie P.-Ehrlich-Str. 67663 Kaiserslautern Prof. Dr. Andreas Podbielski (Gutachter & Betreuer / Reviewer & Supervisor) Uni Rostock Medizin Abt. für Medizinische Mikrobiologie, Virologie und Hygiene Schillingalle 70 18057 Rostock Abgabedatum / date of submission: 30 Januar 2009 Verteidigungsdatum / date of defence: 4 Mai 2009 “Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Deutschen Akademischen Austauschdienstes” Table of content Table of content Abbreviations I. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 I.1 Streptococcus pyogenes as a human pathogen ............................................. 1 I.2 The physiological microflora of the upper respiratory tract ....................... -

Comparison of Surface Proteomes of Adherence Variants of Listeria Monocytogenes Using LC-MS/MS for Identification of Potential Surface Adhesins

pathogens Article Comparison of Surface Proteomes of Adherence Variants of Listeria Monocytogenes Using LC-MS/MS for Identification of Potential Surface Adhesins Hung King Tiong 1,2,†, Steven D. Hartson 3 and Peter M. Muriana 1,2,*,† 1 Department of Animal Science, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078, USA; [email protected] 2 Robert M. Kerr Food & Agricultural Products Centre, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078, USA 3 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK 74078, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-405-744-5563; Fax: +1-405-744-6313 † These authors contributed equally to this work. Academic Editor: Michael Otto Received: 8 January 2016; Accepted: 11 May 2016; Published: 17 May 2016 Abstract: The ability of Listeria monocytogenes to adhere and form biofilms leads to persistence in food processing plants and food-associated listeriosis. The role of specific surface proteins as adhesins to attach Listeria cells to various contact surfaces has not been well characterized to date. In prior research comparing different methods for surface protein extraction, the Ghost urea method revealed cleaner protein content as verified by the least cytoplasmic protein detected in surface extracts using LC-MS/MS. The same technique was utilized to extract and detect surface proteins among two surface-adherent phenotypic strains of L. monocytogenes (i.e., strongly and weakly adherent). Of 640 total proteins detected among planktonic and sessile cells, 21 protein members were exclusively detected in the sessile cells. Relative LC-MS/MS detection and quantification of surface-extracted proteins from the planktonic weakly adherent (CW35) and strongly adherent strains (99-38) were examined by protein mass normalization of proteins.