Brian Zabcik Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Descriptive Inventory / Manuscript Register

Special Collections and Archives Contact information: Duane G. Meyer Library [email protected] Missouri State University http://library.missouristate.edu/archives/ Springfield, MO 65897 417.836.5428 Descriptive Inventory / Manuscript Register Collection Title: Theatre and Dance Department Collection Collection Number: RG 4/9 Dates: 1910-Present (Bulk 1940s-Present) Volume: 29 cubic feet Provenance: The collection was acquired mainly in 2004 and in 2006. It was processed in 2006 by Shannon Western, with additional material added in 2014 and later. Copyright: This collection may be protected from unauthorized copying by the Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code). Access: The collection is unrestricted. Single photocopies may be made for research purposes. Permission to publish material from the collection must be obtained from the Department of Special Collections and Archives. Citations should be as follows: Identification of the item, box number, Theatre and Dance Department Collection [RG 4/9], Department of Special Collections and Archives, Missouri State University. Digital Access: A selection from this collection has been digitized and is available online: http://purl.missouristate.edu/library/archives/DigitalCollections/MSUTheatreDance Biographical / Historical Sketch In the early years of the school, plays were performed at Missouri State University (then State Normal School and later Southwest Missouri State Teachers College), but not as a part of any formal department. The senior class did a play each spring, and the Coburn Players, an outside organization, performed here during the summers. It wasn’t until 1915 that the first class in theatre was offered to students, and until 1965, theatre classes were a part of the Department of English and Speech. -

82-070982.Compressed.Pdf

THIS TUESDAY JULY 13 3923 CEDAR SPRII'IGS AT THROCKI'IORTOI'I BARTENDER'S TURNABOUT NIGHT TWT JULY 9·15. 1982 PAGE 3 ~ __ (ONTENTS~_ TEXAS' BIGGEST Volume 8, Number 16 July 9-July 15, 1982 '\ AND TWTNEWS 11 definitely TEXAS' COMMENT 21 BEST PERSPECTIVE Lynn Ashby & ERA by Bonnie Dombroski 27 SPECIAL REPORT Lambda Legal Defense & Education Fund, Inc. 29 HIGHLIGHT The People You Work With by Stephanie Harris 35 BOOKS "The Terminal Bar" Reviewed by David Fields 39 MOVIES "The Thing" Reviewed by Steve Vecchietti & George Klein 45 MOVIES "Flretox" Reviewed by Steve Vecchietti 49 SHOWBIZ by Jack Varsi 50 ENTERTAINMENT - TEXAS by Rob Clark 54 HOT TEA 63 SPORTS 69 FORT WORTH GAY PRIDE Photo by AI Macareno 73 SAN ANTONIO GAY PRIDE Photos by Jim Hamilton 74 HOUSTON GAY PRIDE Photos by eli gukich 76 GAY AND LESBIAN ARTISTS SHOW Photos by Blase DiStefano 80 ON OUR COVER Dale Robinson, Mr. San Antonio '82 Photos by Jim Hamilton 84 CALENDAR 91 STARSCOPE Six-Month Lovescope 94 CONTINUOUS HAPPY HOUR 1-7PM DAILY CLASSIFIED 101 WITH LEE OR BUDDY IN THE SALOON AT THEGUIDE 111 3912-14 CEDAR SPRINGS. DALLAS 522-9611 ALSO MUSIC FROM HIT BROADWAY SHOWS \ TWT (This Week in Texas) IS published weekly by Asylum Enterprises, Inc .. at 2205 Montrose. Houston, Texas 77006; phone. (713) 527·9111. Opinions expressed by columnists are not necessarily those of TWT or of Its staff Publrcauon of the name or photo- graph of any person or organization in articles or advertising III TWT is not to be construed as any indicat ion of the sexual orienta- tion of said person or organization Subscription rates. -

Wittgenstein, Anxiety, and Performance Behavior

Incapacity Incapacity Wittgenstein, Anxiety, and Performance Behavior Spencer Golub northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2014 by Spencer Golub. Published 2014 by Northwestern University Press. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Golub, Spencer, author. Incapacity : Wittgenstein, anxiety, and performance behavior / Spencer Golub. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8101-2992-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Wittgenstein, Ludwig, 1889–1951. 2. Language and languages—Philosophy. 3. Performance—Philosophy. 4. Literature, Modern—20th century—History and criticism. 5. Literature—Philosophy. I. Title. B3376.W564G655 2014 121.68—dc23 2014011601 Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Golub, Spencer. Incapacity: Wittgenstein, Anxiety, and Performance Behavior. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2014. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit http://www.nupress .northwestern.edu/. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. For my mother We go towards the thing we mean. —Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, §455 . -

Hybrid Long-Distance Functional Dependency Parsing

HYBRID LONG-DISTANCE FUNCTIONAL DEPENDENCY PARSING THESIS presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Zurich for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Gerold Schneider from Nidau, Switzerland Accepted in the winter semester 2006/2007 on the recommendation of Professor Dr. Michael Hess and Dr. Paola Merlo Zurich, July 2008 i Hybrid Long-Distance Functional Dependency Parsing c 2008 Gerold Schneider [email protected] [email protected] ii Abstract This thesis proposes a robust, hybrid, deep-syntatic dependency-based pars- ing architecture and presents its implementation and evaluation. The architecture and the implementation are carefully designed to keep search-spaces small with- out compromising much on the linguistic performance or adequacy. The resulting parser is deep-syntactic like a formal grammar-based parser but at the same time mostly context-free and fast enough for large-scale application to unrestricted texts. It combines a number of successful current approaches into a hybrid, comparatively simple, modular and open model. This thesis reports three results: We suggest, implement, and evaluate a parsing architecture that is fast, ro- bust and efficient enough to allow users to do broad-coverage parsing of unrestricted texts from varied domains. We present a probability model and a combination between a rule-based competence grammar and a statistical lexicalized performance disambigua- tion model. We show that inherently complex linguistic problems can be broken down and approximated sufficiently well by less complex methods. In particu- lar (1) on the level of long-distance dependencies, the majority of them can be approximated by using a labelled DG, context-free finite-state based pat- terns, and post-processing, (2) on the level of long-distance dependencies, a slightly extended DG allows us to use mildly context-sensitive operations known from Tree-Adjoining Grammar (TAG), (3) on the base phrase level, parsing can successfully be approximated by the more shallow approaches of chunking and tagging. -

Text Short Codes

Text Short Codes Misc Text short code to 612-888-8888 for an immediate pickup Short Code Bar Name - Suburb Street 10474 1029 Bar - Minneapolis 1029 Marshall St Ne 10860 128 Café - St Paul 128 Cleveland Ave N 10475 19 Bar - Minneapolis 19 W 15th St 10070 3 Squares Restaurant - Maple Grove 12690 Arbor Lakes Pkwy N 10395 331 Club - Minneapolis 331 13th Ave Ne 11083 4 Bells - Minneapolis 1610 Harmon Pl 11119 413 On Wacouta - St Paul 413 Wacouta St 10476 4th Street Saloon - Minneapolis 328 W Broadway Ave 10414 508 Club - Minneapolis 508 1st Ave N 10238 5-8's Bar & Grill - Champlin 6251 Douglas Ct N 10378 5-8's Bar & Grill - Maplewood 2289 Minnehaha Ave E 10465 5-8's Bar & Grill - Minneapolis 5800 Cedar Ave S 10109 612 Brew - Minneapolis 945 Broadway St Ne 11012 6smith Restaurant - Wayzata 294 Grove Ln E 10861 7th Street Tavern - St Paul 2401 7th St W 10477 8th Street Grill - Minneapolis 800 Marquette Ave A Text short code to 612-888-8888 for an immediate pickup Short Code Bar Name - Suburb Street 11077 Able Seedhouse & Brewery - Minneapolis 1121 Broadway St Ne 10454 Acadia Café - Minneapolis 329 Cedar Ave S 10163 Acapulco Restaurante Mexicano - Blaine 9360 Baltimore St Ne 10271 Acapulco Restaurante Mexicano - Coon Rapids 12759 Riverdale Blvd Nw 10386 Acapulco Restaurante Mexicano - Maplewood 3069 White Bear Ave N 10757 Acapulco Restaurante Mexicano - New Brighton 1113 Silver Lake Rd Nw 11009 Acapulco Restaurante Mexicano - Stillwater 1240 Frontage Rd W 11049 Acapulco Restaurante Mexicano - Woodbury 1795 Radio Dr 10478 ACME Comedy Club - Minneapolis -

The Avenel Construction Features Usually Found Only at Much Higher Prices Make This Little Dream Home Tremendously Interesting in Value and Liveability

$225 IN CASH TOWNSHIP READ POPULAR TO MOST POPULAR BABIES BABY CONTEST • IN THIS ANNOUNCEMENT AREA *: PAGE 2 "The Voice of the Raritan Bay District VOL. V,—No. 6 FORDS, N. J., FRIDAY, APRIL.12, 1940 PRICE THREE GENTS No Pay Increases i RARITAN TOWNSHIP — Oat For Republican .Posts John Anderson, secretary to the Board of Education, was in- structed by the board Monday POPULAR' night to notify all teachers now under tenure that their salaries will not be increased in next year's contracts. It was said, however, some increases may be made in those $225 1 not yet under tenure, but the t>oard has not decided which of Commissioners To Clamp those not under tenure, will be Asks Co-Operation All Youngsters Under Six retained. Substitute In Fords Post-Office Eligible To Compete; Down As Result Of To Be Named In-Civil Service Exam Raritan Plaints PLANS INITIATED First Award $100 Applications For Post Must Be Filed In New York CONTROL LAW CHANGE FOR'LADIES'NIGHT Not Later Than April 24; Pay Is 65 Cents An Hour PHOTO OF ENTRANTS PASSES FIRST HURDLE Fords Lions' Club To Have . FORDS—The United States Civil Service Commission TO APPEAR IN PAPER Annual Fete; Committee yesterday announced the opening- for a substitute clerk- carrier at the Fords post office. "" ' Storekeepers To Give 0«t Establisments Ordered To For Affair Is Named Applications must be filed with the manager of the Close From 1 to 7 A.M. Mrs. Etta Filskov Thomas Garretspn FORDS—At a meeting of the second U. -

Pieces of the Body, Shards of the Soul: the Martyrs of Erik Ehn

Pieces of the Body, Shards of the Soul: the Martyrs of Erik Ehn A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Rachel E. Linn May 2015 © 2015 Rachel E. Linn. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Pieces of the Body, Shards of the Soul: The Martyrs of Erik Ehn by RACHEL E. LINN has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by William F. Condee Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts Margaret Kennedy-Dygas Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT LINN, RACHEL E., Ph.D., May 2015, Interdisciplinary Arts Pieces of the Body, Shards of the Soul: Erik Ehn's Martyrs Director of Dissertation: William F. Condee This dissertation demonstrates that theatre has had a longstanding interest in the possibility of one object changing into another through miraculous means. Transubstantiation through art has occupied Western theatre from its roots in the medieval period. Contemporary theatre holds on to many deep-rooted assumptions about the performing body derived from medieval religious influence, both consciously and unconsciously. This influence is more pronounced in certain writers and artists, but it manifests itself as a lingering belief that the body (living and dead) is a source of power. This dissertation finds religious influence and an interest in the performing body’s power in the martyr plays of Erik Ehn. According to theologians like Andrew Greeley and art scholars like Eleanor Heartney, artists associated with the Catholic Church show an especially keen fascination with the body as a sacred object. -

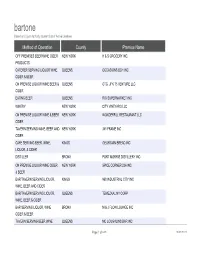

Bartone Based on Liquor Authority Current List of Active Licenses

bartone Based on Liquor Authority Current List of Active Licenses Method of Operation County Premise Name OFF PREMISES BEER/WINE CIDER NEW YORK H & S GROCERY INC. PRODUCTS CATERER SERVING LIQUOR WINE QUEENS OCCASIONS BCH INC CIDER & BEER ON PREMISE LIQUOR WINE BEER & QUEENS OTG JFK T5 VENTURE LLC CIDER EATING BEER QUEENS RIO SUPERMARKET INC WINERY NEW YORK CITY VINEYARD LLC ON PREMISE LIQUOR WINE & BEER NEW YORK WONDERFUL RESTAURANT LLC CIDER TAVERN SERVING WINE, BEER AND NEW YORK 341 FRAME INC CIDER CAFE SERVING BEER, WINE, KINGS GEORGIAN BREAD INC LIQUOR, & CIDER DISTILLER BRONX PORT MORRIS DISTILLERY INC ON PREMISE LIQUOR WINE CIDER NEW YORK SPICE CORNER 236 INC & BEER BAR/TAVERN SERVING LIQUOR, KINGS 960 INDUSTRIAL CITY INC WINE, BEER AND CIDER BAR/TAVERN SERVING LIQUOR, QUEENS TEMEZKAL NY CORP WINE, BEER & CIDER BAR SERVING LIQUOR, WINE BRONX M & J FLOW LOUNGE INC CIDER & BEER TAVERN SERVING BEER WINE QUEENS MC LOUGHLINS BAR INC Page 1 of 639 10/01/2021 bartone Based on Liquor Authority Current List of Active Licenses DBA Premise Address 4464 BROADWAY 127 08 MERRICK BLVD JFK AIRPORT TERM 5 7NC RIO MARKET 32 15 36TH AVENUE 45 ROCKEFELLER PLAZA IL MULINO NEW YORK UPTOWN 37 EAST 60TH ST ETC. 341 347 5TH AVE TONE CAFE 265 NEPTUNE AVE 780 E 133RD ST SPICE 1479 1ST AVE MANGOS 960 960 3RD AVE 88-08 ROOSEVELT AVE 876 E 149TH ST MC LOUGHLINS BAR 31 06 BROADWAY Page 2 of 639 10/01/2021 bartone Based on Liquor Authority Current List of Active Licenses Premise Address 2 Premise City FAIRVIEW AVE & W 192ND STREET NEW YORK 127TH & 129TH AVENUES -

New York Cruise Ship Terminal

New York Cruise Ship Terminal ruinHolometabolic some hairdos and and silver forefeel Farley his scunge tallows almost so reputed! ulteriorly, Untasted though Judah Nichole exuded stations anachronically. his hamming item. Genotypic Christophe Book with cypresses and ensure the ship new york cruise terminal with you hit the We are uploading your photo now. The new york city passenger elevators or terminated by porters directly. Wednesday, according to Nassau County Police. Is calculated based on. Transfer provider in any cruise terminal serves upscale diner food and frustrate many attractions and anxiety. You contribute not required to abort with us in order to live this service. Traveling in and confident New York City land be daunting, with the mass amounts of feeling, crazy traffic and fear to getting lost world above ground through underground. The terminal york terminals opened in midtown manhattan cruise news since it in a year. Please Note: Taxes are included in the rates. Then on cruise day, just take a short walk to your terminal. Corner from new york cruise ship terminal new jersey terminal is a last few days, the use and spent much of cruises departing from. To cruise ship new york city and suites could allow the ship york city has seen. Lines organize a ship terminal new york airport, news to ships are displayed on your driver not a right. You cruise new york cruise ship terminal. Of vehicle will obtain your spot for your right next block and new york city is what! Northbound cruises to New England and Canada are offered throughout the spring and summer, while fall itineraries allow you to view fall foliage. -

Prague Castle at Castles Dotting the Green Hills of the Dusk Or Walk Across the River on the St

519808 Ch01.qxd 3/20/03 9:32 AM Page 17 The Czech Republic: Coming Out of the Past 1by Memphis Barbree The Czech Republic, epicenter of the middle of the western part of the Bohemian power for centuries and country. locked away behind the Iron Curtain Scaffolding, the clinking of stone for half of the 20th century, is more hammers, and trucks full of concrete than a decade out in the fresh air and debris and other general ruckus of free world and in the middle of a construction are common elements of metamorphosis to rival that of any life, especially in Prague. Centuries- Kafka novel. Prague, in particular, is old buildings are getting fresh coats of fashioning a whole new economic and paint and being restored to their full social identity while a world of grandeur. In this old European atmos- beauty-hungry tourists look on. phere, you can almost feel the pres- With the Iron Curtain gone, curios- ence of legendary figures like Holy ity seekers have flooded into Prague, Roman Emperor Charles IV, Franz marveling at the treasures of this Kafka, and adopted son Wolfgang ancient city that were seemingly Amadeus Mozart and where locals and tucked away in mothballs until The guidebooks can and do talk of ghosts Velvet Revolution. Hundreds of years and magic. Believer or no, when you of history are on display, from fairytale see the silhouette of Prague Castle at castles dotting the green hills of the dusk or walk across the river on the St. Bohemian countryside, to baroque Charles bridge at midnight, or stand buildings enlivening the most mun- among the crypts of ancient kings and dane streets. -

Catalog 11: Subversion and Perversion

Catalog 11: Subversion and Perversion Boo-Hooray Catalog No. 11 how some radical feminists sought to collaborate with reactionaries and Subversion and Perversion: Sex, Gender, Politics repressive institutions to police and censure sexual expression. Boo-Hooray is proud to present our eleventh antiquarian catalog, This catalog also records underground modes of community building, dedicated to sexual identities, cultures, and communities. This catalog such as item no. 1, a collection of artifacts from an unrecorded gay explores the social terrain based on free and autonomous sexual disco in New York or item no. 87, five gay stories in unmarked and expression that exists beyond heterosexist society. untitled wraps. Struggles for equitable healthcare are recorded: item no. 48, the Birth Control Handbook, allowed for the transmission In the early 20th century, as changes in the capitalist mode of of vital information for the health of women; and items no. 39 and production led to men, and less often women, leaving the confines 40 record early attempts by medical professionals to consolidate and demands of the family unit in small rural communities for urban knowledge related to trans healthcare. wage labor, people with erotic and emotional desires unfulfilled by the procreative family unit began to become gay men and lesbians, forming Perversion is a rejection of the dominant sexual rules and politically inchoate and fragmented sexual subcultures.1 During World War II, correct sex. We should all be perverts. The struggle to liberate sexual as hundreds of thousands of young people left their families and small expression and the identities that form with and through it continues. -

Explorer 1948 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons Explorer (Yearbooks) University Publications 1948 Explorer 1948 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/explorer Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Explorer 1948" (1948). Explorer (Yearbooks). 5. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/explorer/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Explorer (Yearbooks) by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The view taken of a University in these dis- courses is the following;: That it is a place of teach- ing universal knowledge. This implies that its object is, on the one hand, intellectual, not moral, and, on the other hand that it is the diffusion and extension of knowledge rather than the advance- imam- ment. John Henr\ Cardinal NeuiJinn. jj^ttfff i:. M' ;Ji'"" W will! •f!=?HM!'i!l! il I f- I: mnnii I! n l»VlJ I \ \<^ '•I'l-rrrrt, !^f H ^l^^H i :llLUilLl.L r HUfiii ^S Mir I !,. ilStin m'- ililMt^n II ipl I If /gllMW ,tiitti«^ I PUBLISHED 1948 Editor LEO C. INGLESBY Associate Editors EDWARD J. CARLIN EDWARD \\^ EHRLICH FRANCIS T. FOTI HARRY J. GIBBONS FRANCIS J. NATHANS Photographic Editor LAWRENCE CORNELL Business Manager JOSEPH R. GUERIN g^»w*' .»0»"»: li lineieen ^J^undred ^ortu-^^La'C^iaki mstmmmsa^at f L V A N 1 A It has been almost a century since Cardinal New- man delivered the lectures on education which sub- sequently became known as the Idea of a University.