CEDAW) 58Th Session, June 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hariyo Ban Program Ii Threats and Vulnerabilities

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM II (2016-2021) THREATS AND VULNERABILITIES ASSESSMENT OF PARKS AND CORRIDORS OF TERAI ARC LANDSCAPE Prepared by: WWF in partnership with CARE, FECOFUN and NTNC P.O. Box 7660 Kathmandu, Nepal 21 April 2017 © WWF 2017 All rights reserved Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part must mention the title and credit WWF. Published by WWF Nepal PO Box: 7660 Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal T: +977 1 4434820, F: +977 1 4438458 [email protected] , www.wwfnepal.org/hariyobanprogram Disclaimer This Threats and Vulnerabilities Assessment of Parks and Corridors in Terai Arc Landscape is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................5 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................................6 Chitwan National Park and Buffer Zone ...................................................................................................................7 Threat Ratings of Chitwan National Park and Buffer Zone...................................................................................8 Barandabhar Corridor ........................................................................................................................................... -

Assessment of Poaching and Illegal Wildlife Trafficking in Banke- Kamdi Complex

Assessment of Poaching and Illegal Wildlife Trafficking in Banke- Kamdi Complex Submitted to: Hariyo Ban Program Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: People’s Help Group (PHG) Kathmandu, Nepal July, 2017 © WWF Nepal 2017 All rights reserved Disclaimer: This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the responsibility of People’s Help Group (PHG) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Executive Summary Wildlife crime is a serious issue in conservation particularly of the threatened species of wild flora and fauna globally. Several endangered species such as Asian big cats, elephants and rhinoceros are at the verge of extinction if the current trend of wildlife crime is not retarded. The illegal wildlife trade is among the leading causes for rapid wildlife species decline worldwide (McMurray, 2008). Similarly, Nepal cannot be exception to this situation; the country has been known as transit for illegal wildlife trade and a source for some of the illegally traded species such as rhino horns, tiger and leopard pelts and pangolin scales. Despite various efforts to control wildlife crime, such crime still exists sporadically and in low volume in the country. The Banke-Kamdi complex is located in the (Mid-western region, State No.6) and covers part of Banke, Dang and Salyan districts. This Complex comprises of Banke National Park (BaNP), its Buffer Zone and Kamdi forest corridor. At present, Kamdi Corridor is under the Banke District Forest and is one of the most important biological corridors of Tarai Arc Landscape. -

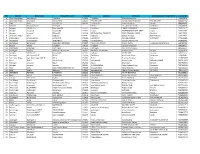

Devipatan Zone CSC List

Grampanchayat District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name Bahraich Bahraich1 Hathiya Bojhi 271881 hathiya bojhi Farooq Ansari 7054482275 Bahraich Behriach Chittaura(R) 271801 Samsa tarhar Adarsh Kumar Gautam Samsa tarhar 7054693883 Bahraich Bahraich Nanpara 271865 chaugodwa nawabganj Arman Ahmad Chaugorwa 7081092832 Bahraich Bahraich Mahasi 271801 Saraswati nagar India Itech_Lait Kumar bajpaiMahasi 7275011100 Bahraich Vishveshwarganj Bhagirathpurwa Nethiya 271821 Bhagirathpurwa Nethiya VASUDEV PRASAD CHAUHAN 7275248043 Bahraich Nawabganj Umariya 271881 Umriya (Nandagaon) Shrawan Kumar Verma 7376126247 Bahraich Bahraich-NIELIT MIHINPURWA 271855 GANGAPUR AKHILESH PRATAP SINGH GANGAPUR 7376145900 Bahraich Behriach Balha(R) 271865 Sugar Factory, Nanpara Deepak Kumar Siletanganj 7376640895 Bahraich Jarwal Naraunda 271872 Naraunda Deepak kumar pal 7379293493 Bahraich Mihinpurwa Bojhiya 271855 Bojhiya Bazar OM PRAKASH 7379566421 Bahraich Behriach Mihipurwa(R) 271855 Madhwapur Om Prakash Madhwapur 7379568921 Bahraich Behriach1 Mihipurwa(R) 271855 Rampurwa Satish Kumar Rampurwa 7379892297 Bahraich Bahraich-NIELIT Bahraich 271801 Banhraich Asiya Begum Bahraich 7388238777 Bahraich Bahraich-NIELIT KAISERGANJ 271903 KAISERGANJ SATISH KUMAR SRIVASTAVADIHVASHER BAHADUR SINGH7398192862 Bahraich Bahraich Etawah 271865 Nanpara Azhar Ali SARAIYAN 7398196031 Bahraich Behriach Bahraich(U) 271801 Bahraich(U) Jaleel Ahmed Dargah Shareef 7398203894 Bahraich Huzoorpur Shivnaha 271872 Shivnaha Ritu srivastava Dewanpur -

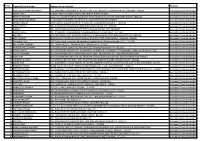

Sno District Block Name Village/CSC Name Pincode Location VLE Name Grampanchayat Village Name Contact No 1 Sant Kabir Nagar Semr

SNo District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Grampanchayat Village Name Contact No 1 Sant Kabir Nagar Semriyawan Tekensha 272125 Tekensha Mohammad Azam 789660973 2 Sant Kabir Nagar S K nagar3 MEHDAWAL 272271 PACHNEVARI ASHOK KUMAR MISHRA PACHNEVARI 840040772 3 Mau MAU RATANPURA 121705 Haldhar Pur Brijesh chauhan Ratohi 888069301 4 Varanasi Varanasi-NIELIT chollapur LANKA CIC_Manish Pandey Chollapur 896088439 5 Jaunpur JAUNPUR5 Ram nagar(R) 222137 Jamalapur LAXMI CHAURASIA Jamalapur 900559551 6 Jaunpur Jaunpur6 Jaunpur(R) 222139 Lapari MOHAMMAD AJMAL SHAH Lapari 904471787 7 Jaunpur Jaunpur1 Sirkoni(R) 222138 DR SHYAMLAL PRAJAPATI GYAN PRAKASH YADAV Gaddipur 964290095 8 Ambedkar Nagar Bhiti Naghara 224141 Naghara Gunjan Pandey Balal Paikauli 979214477 9 Maharajganj Maharajganj2 LAXMIPUR 273164 LAXMIPUR RAMESH KUMAR SURYAPUR 979416162 10 Gorakhpur Kempiyarganj Jangal Bihuli 273001 JUNGLE BIHULI SANJAY SRIVASTAVA 979456745 11 Gorakhpur Gorakhpur Jungle Beni Madho(U) 273007 Neaer Shiv Mandir Brijesh Kumar Jungle Beni Madho No.2 980792705 12 Deoria Bhatni Singhpur 274705 Singhpur Ugrasen Chaurasia 984188375 13 Chitrakoot Ramnagar Ram Nagar 245856 ramnagar Ravi Shanker Gupta 985632647 14 Azamgarh Koyalsa Molnapur Nathnpatti 246141 Molnapur Nathnpatti Ramesh Yadav Pasipur 993605118 15 Jaunpur JAUNPUR4 Barsathi(R) 222162 Ojhapur SUJIT PATEL Jarauta 994245307 16 Mirzapur Mirzapur-NIELIT Sikhar 231306 Pachranw Atul Kumar Singh pachranw 995695683 17 Sant Kabir Nagar Sant Kabir Nagar-NIELIT Belrai 451586 Belrai Pradeep Srivastav -

Unclaimed Amount

Sr No Name Of Policy Holder Address As per Records Reasons 1 SANTOSH KUMAR PANIGRAHI C/O-MARKAND PANIGRAHI AT-REDDY STREET PO-LANJIPALLI BERHAMPUR DIST-GANJAM -760008 Surrender/Force Surrender 2 SHANTI DEVI SADAR HOSPITAL PO&DIST KHAGARIA BIHAR BIHAR -851204 Surrender/Force Surrender 3 PRAYAG PASWAN S/O LATE GHUNNI PASWAN VILL DHANHAR PO WARIS NAGAR DIST SAMASTIPUR BIHAR -848133 Surrender/Force Surrender 4 MANOHARI GAWARIYA C/ LALARAM GAWARIYA HOUSE NO, 90 GAWARIYON KA BAS BIKANER -...... Surrender/Force Surrender 5 HABED AHMAD .. BABULLAH VILL-JAJAR GATHIYA PO-MAU DIST-SIDDHARTH NAGAR U.P -272153 Surrender/Force Surrender 6 JULFEKAR ALI .. VILL-NAUAR DAR PO-GANGOLI DIST-SANTKABIR NAGAR U.P -272175 Surrender/Force Surrender 7 NANKE .. VILL KIDDHIYAWAN PURWA POST PUREY PRASAD BHINGA DIST SRAWASTI -.. Surrender/Force Surrender 8 CHINTA DEVI VILL-PIPARAPATTI BAHORAPUR PO-GARHMALPUR DIST-BALLIA UP -221709 Surrender/Force Surrender 9 MUSTAK .. S/O MR MALUSHAH JI WARDNO-1 IDGAH KE PASS MANGROL DIST-BARAN RAJASTHAN -325215 Surrender/Force Surrender 10 NITU TIWARI W/O SANJAY TIWARI VILL-IMILIYA(GOSAI KA PURA) POST-HAIDARGANJ FAIZABAD -224205 Surrender/Force Surrender 11 Phoolwati Devi 395 Kanjoli Ansh Govindpur Bhag Kanjoli Sadabad Distt. Mahamayanagar (U.P.) -281306 Surrender/Force Surrender 12 RAJ KUMAR SHARMA VILL PACHAURI POST PACHAURI DIST GHAZIPUR UP -232327 Surrender/Force Surrender 13 MAMTA ANIL DAWANE AT-UCCHALI POST DANDI TAL PALGHAR DIST THANE MAHARASHTRA -401501 Surrender/Force Surrender 14 GOPAL SINGH S/O SRI TOOFAN SINGH HN.72-K SARPANCH SA WALI GALI BIDMANDI TEH-RAMGANJ MANDI KOTA RAJASTHAN -.. Surrender/Force Surrender 15 GOPAL RATHORE S/O SRI NANDRAM RATHORE BEHIND NEW TEHSIL PACHPAHAR DIST-JHALAWAR RAJASTHAN -. -

Monsoon Preparedness Assessment: 14 Earthquake Affected Priority Districts and the Terai Districts

MONSOON PREPAREDNESS ASSESSMENT: 14 EARTHQUAKE AFFECTED PRIORITY DISTRICTS AND THE TERAI DISTRICTS FINAL REPORT NEPAL 2016 Monsoon Preparedness Assessment, Nepal 2016 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The annual monsoon season typically occurs in Nepal during July and August, with heavy rains and winds damaging housing, roads and other infrastructure as well as bringing increased flood and landslide risk. Ahead of the 2016 monsoon, concerns were raised that destabilization in terrain conditions caused by the 2015 earthquakes could significantly increase the risk of landslides during monsoon rains, both in areas historically prone to landslides and flash floods and areas that have become susceptible following the earthquakes. Furthermore, heavy rains could trigger the movement of loose rubble accumulated by the co-seismic landslides that followed the earthquakes.1 In preparation for the 2016 monsoon, the Shelter Cluster was developing a contingency plan focusing on the 14 earthquake priority districts2, along with the 22 Terai districts3 that have in the past been affected by widespread flooding during monsoon seasons. This assessment was launched to inform this planning through a macro-level analysis secondary data to identify areas vulnerable to monsoon impacts and estimate potential caseloads; along with collection and analysis of primary data to understand expectations of assistance, level of preparation and potential coping strategies, with a specific focus on families living in emergency (tents/tarpaulin) or temporary (CGI) shelter. While addressing the assessment objectives, the study also generated findings on underlying vulnerabilities amongst populations at risk of monsoon impacts. Key findings are summarised below. Landslide hazard and flood risk mapping Using post 2015 earthquake landslide susceptibility data, the Village Development Committees (VDCs)4 across all 14 earthquake affected priority districts were classified as having low, medium or high landslide susceptibility5 (see Map 1). -

Master Plan of Bansgadhi.Pdf

PROJECT INFORMATION Name of the Project Consulting services for Preparation of Integrated Urban Development Plan of Bansgadhi Municipality, Bardiya Contract ID DUDBC/CS-QCBS-04-074/75 Project Executing Agency Government of Nepal, Ministry of Urban Development Department of Urban Development & Building Construction Babarmahal, Kathmandu, Nepal Name of the JV Consultant Naya Rastriya Engineering Consultancy Pvt. Ltd.- Moonlight Civil Solution Pvt. Ltd-Green Innovative Pvt. Ltd (NREC-MCS-GI JV) Project Commencement Date 2075-02-09 Projected Date of Completion 2075-11-08 SUBMISSION INFORMATION Name of the Report Consulting services for Preparation of Integrated Urban Development Plan of Bansgadhi Municipality, Bardiya Nos. of Volume I Volume Information Final Report Date of Submission ……………………………………… Submission Type Hard Copy Copies Produced 7 Copy Prepared By ……………………… Checked By ………………………… Reviewed By …………………………. Official Stamp ………………. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Final Report on preparation of Integrated Urban Development Plan of Bansgadhi Municipality of Bardiya District has been prepared as per the ToR provided along with the contract agreement. We are grateful to entire individuals who directly or indirectly helped us during data collection, analyzing, workshop conduction and preparation of final documents. We are greatly indebted to the constant support, interest and feedback of Mr. Salikram Adhikari, Mayor and Mrs. Sushma Chaudhary, Deputy Mayor of Bansgadhi Municipality. We also express our sincere thanks to Chairpersons and members of -

CEDAW) 58Th Session, June 2014

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) 58th session, June 2014 Fourth and Fifth Review – India THE RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD OF WOMEN IN INDIA Submitted by FIAN India 1. HUNGER AND MALNUTRITION IN INDIA As per the State of Food Insecurity in the World1, India remains home to the largest number of undernourished people in the world: 213 million (17% of its population) between 2011 and 2013. Considering various poverty norms, about 75% of the Indian population suffers from hunger and malnutrition to varying degrees, 50% of it acutely. The Global Hunger Index (GHI) ranks India at 63 with a score of 21.3 among 120 countries, classifying its situation as within the ‘alarming’ category2. The report also noted that India continued to record one of the highest prevalences of children under five who are underweight, at more than 40%, and is among the countries with the highest prevalence of anemia, which affects 51% of women in the age bracket of 15-59 years and 87% of pregnant women. More than 70% of Indian women and children have serious nutritional deficiencies. Similarly, the level of adult malnutrition is high, affecting one-third of the country’s adults. In this regard, Scheduled Tribes (STs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), and minorities (Muslims) are at a great disadvantage. As per India’s State Hunger Index (ISHI), 12 of the 17 states surveyed fall into the ‘alarming’ category and one into the ‘extremely alarming’ category. These 17 major states comprise 95% of total population of India3. About 68.84% of the population of India is rural, the majority of whom greatly suffers from hunger and malnutrition. -

Evidence-Based Initiatives of FIAN Nepal on Right to Food Policies, Programmes & Practices in Nepal

Evidence-based Initiatives of FIAN Nepal on Right to Food Policies, Programmes & Practices in Nepal Editors: Prof. Dr. Keshab Khadka Basant Adhikari Nirmal Gadal Buddhi Ram Chaudhary Mabin Ghale Food-first Information and Action Network (FIAN) Nepal © FIAN Nepal, 2014 Published by: Food-first Information and Action Network (FIAN) Nepal Kupondole, Lalitpur, P.O. Box: 11363 Tel.: +977-1-5011609, 5527152, 5527650 Fax: +977-1-5527834 Website: http://www.fiannepal.org Email: [email protected] Disclaimer: The information and opinions presented in the research studies are entirely of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the official views and opinions of FIAN Nepal to which the writers are affiliated. Acknowledgement FIAN Nepal has identified six thematic areas towards strengthening right to food movement in Nepal. They are: 1. food and access to natural resource and services, 2. right to water (inclusive of access to irrigation, water privatization distortions and access to safe drinking water), 3. agricultural inputs (i.e., seeds, fertilizers, government services, resource mobilization), 4. women/marginalized sections/Dalits, 5. extra territorial obligations, and 6 . food aid and labour (farm labour and diaspora). Since its establishment, FIAN Nepal is exploring these thematic areas and advocating for the protection and promotion of human right to food, with specific focus on vulnerable people and communities of Nepal. In this process, FIAN Nepal has pursued evidence- based analyses on the above thematic areas either by making use of case studies or researches, the results of which are compiled here - as research works on Food Aid, Access to Natural Resources, Seed Policy, and Climate Change. -

ALLAHABAD BANK.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE POST BOX NO. 304 PORT BLAIR 744101 ANDAMAN & ANDAMAN NICOBAR ISLAND PARTHO AND PORT BLAIR PRATIM NICOBAR ANDAMAN&NICOBAR NASKAR,N ISLAND ANDAMAN PORT BLAIR 744101 PORT BLAIR ALLA0211921 M SINHA 03192-230267 P VISWAPAT VILLAGE & POST HI,9441421 OFFICE 507,KGK KGK ANDHRA SOAN,NIRMAL MURTHY,9 MURTHY,94901 PRADESH ADILABAD SOAN TALUK, PIN-504105 SOAN ALLA0210743 490120996 20996 ANANTAPUR BRANCH, CHANDRA ARCADE, PLOT O VIJAY NO.150,SHIRDINAGA KUMA, ANDHRA R, ANANTAPUR- ANANTAPU 900076928 T EESHWARI, PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTAPUR 515001 R ALLA0212684 4 9963627116 OPP. V.V. MAHAL, MOSQUE ROAD, CHITTOOR DISTRICT V KUMAR, ANDHRA TIRUPATI ANDHRA M VIJAY PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI PRADESH 517501 TIRUPATI ALLA0211475 KUMAR 0877-2220722 CUDDAPAH BRANCH, OPP:NALLARATHI MIDHE G SASHI N BHAGYANAGAR KUMAR, RANGANAYAK ANDHRA COLONY, CUDDAPAH- 990858207 ULU, PRADESH CUDDAPAH CUDDAPAH 51600 CUDDAPAH ALLA0212683 3 9966752862 Uma Maheswar Rao, DOOR NO.1-4-16 BY 996675286 1 BY 2, MAIN ROAD, 2, Rahul AMLAPURAM. EAST George GODAVARI DIST.PIN Verghese, ANDHRA EAST 533201. ANDHRA AMALAPUR 900056749 PRADESH GODAVARI AMALAPURAM PRADESH AM ALLA0213058 7 20-1/2A, MUMIDI SHOPING COMPLX (1ST FLOOR), MAIN ROAD, KAKINADA EAST GODAVARI ANDHRA EAST DISTRICT ANDHRA P RAO, S A PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA PRADESH 533001 KAKINADA ALLA0210459 RAO 0884-237307 ALLAHABAD BANK, SAIRAM AVENUE, 2-4- MALLADI 1049, PLOT NO.35, LAKSHMA NEW NAGOLE, NA MRUDULA KOTHAPET ROAD, KUMAR: PRIYADARSINI: ANDHRA EAST HYDERABAD-500035 KOTHAPET 990821451 9440542726,040 PRADESH GODAVARI KOTHAPET AP A ALLA0212741 3 24045252 500010019 Uma D.NO.1-99, MAIN Maheswar ROAD, NEAR Rao, PANCHYAT OFFICE, 996675286 KOVVADA,KAKINADA 2, Rahul RURAL George MANDALEAST Verghese, ANDHRA EAST GODAVARI DIST.- 900056749 PRADESH GODAVARI KOVVADA 533006 KAKINADA ALLA0213061 7 D.NO.46-15-17, NEAR MAHATMA GANDHI PARK,DANAVAI PET,RAJAHMUNDRY DIST. -

Nepal Coronavirus Civacts Campaign EN-Issue30

Nepal Coronavirus CivActs Issue #30 Campaign 28.05.2020 The Coronavirus CivActs Campaign (CCC) gathers rumours, concerns and questions from communities across Nepal to eliminate information gaps between the government, media, NGOs and citizens. By providing the public with facts, the CCC ensures a better understanding of needs regarding the coronavirus and debunks rumours before they can do more harm. Tested PCR: 60,696 RDT: 102,034 Positive: 1,042 Active: 850 Deaths: 5 NEPAL Thimi Mayor Madan Sundar Shrestha at the municipality hospital inspecting molecular testing equipment for COVID-19. Source: https://covid19.mohp.gov.np/#/ Foreign Employment and Remittance Inflow 193,880 New Labor Permits 24.2 Growth Rate 17,553 Renewed Labor -2.7 Growth Rate Permits 1.8 Remittance Inflow 369,433 Total Individuals for Growth Rate Rs. 592B 9.8 Growth Rate Foreign Employment Fiscal Year 2076/77 The remittance inflow in the fiscal year 2075/76 was Rs. 879 billion whereas the inflow in the first 8 months of fiscal year 2076/77 was Rs. 592 billion. In the current situation, there is no possibility of an increase in remittance inflow. This can put pressure on the next year’s GDP as well as foreign exchange reserves. Source: https://mof.gov.np/ N E P A L Rumors & Facts There is an ongoing fear The treasury steering committee of the Corona Prevention, Control and that with the increase in Treatment Fund of Nepal Government has made a decision and informed the number of infected all the 7 provincial governments that the amount from the fund can be cases, the government has channeled if the province makes a request along with the required map, run out of resources and is design and an estimated budget to establish a quarantine with 1000 bed unable to manage facilities capacity following the standard criteria and to build a temporary including isolation wards infrastructure for isolation wards anticipating the infection numbers or to and quarantine which renovate the existing infrastructure for the arrangement. -

District Census Handbook, Bahraich, Part XII-B, Series-25, Uttar Prades

CENSUS 1991 I J}f~()11-25 SERIES-25 \3ct1x ~ ~~) UTTAR PRADESH 1WT-XII€J PART-XllB 'UIJOi q ':PI{lll VILLAGE & TOWNWISE PRIMARY CENSUS m~r1CJ) \J1"1~1 0111 ABSTRACT fi 1'< fU1(q I ,iF"PI 01~1 5'R1 gRdCPI DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK N1(Y11 616'<1~:q DISTRICT BAHRAICH f.i~~Ict> \JFPIOI~I ~ DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS UTTAR PRADESH ~~ L _j 1. !OI ffi Iq "'II I 2. ~ V 3. ~ q)T ...."'I .... ,"1.,.f;~~?1 4. ~ cfi "'I6~'{uf ~ • -~~. IX 5. ~ \if "1 "I 01"11 5'R1~R<1q)1 ~-!J:1;.ti1_~T~ ~m~~I"'" " XIX 6. FchJlt1l ollt"'l q) Rcq of! 1 7. ~ ~ \if "'I "I 01"11 ~ 16 8. ~ 14\ 0 1 / "i'lfi U ~ ':'::\Jfr::"i~'lmOT:I"'''''1 ~ 3{- (i) 4J14) 0 1 "'I1"'~?1 ~ ~ .,.."\Jf="1...,.,,....,o..... I"1~1 ~ 1 '{11!1~'~q) ~ ~ fl\it"1:i'<Ql 24 2 'HljGI~q) fmnm ~ "1Qliil l '\iI 42 3 'H15GI~Ch fmnm ~-1lQm 56 4 '{1ljGI~Cf) fmnm ~-~ 66 5 'HljGlftlq; fctcpm ~-mmrr 80 6 'Hlj~I~Cf) fmnm ~ Gt"'l'ji51 96 7 'HljGlftlCh fctcpm ~-~ 114 8 'HljGI~Cf) fctcpm ~ fll~t'11 134 9 tlljGIft!ct> ~ ~ MU'.'g:< 154 10 'HljGIft!Cf) 'Fctcl;m ~ Fchhl"("iGt 168 11 'HljGlftlCh fmnm ~-~ 180 12 'Hlj~lftlCf) ftlq;m ~-~ 196 13 'HljGIft!ct> 'Fctcl;m ~ dGtql~'( 214 14 'HI j~ I~ Cf) fctcIm:T ~ 4i,<cll S'< 228 15 'H'5~'~q) ftlq;m ~ 5"1'<31( 248 16 'H15GlftlCf) fctcIm:T ~ $'H,,(ljGt 268 17 'HljGI~ct> ~ ~-~ 288 18 tlI5GI~Cf) ~ ~ eR6'<3'< ~ 308 19 'HljGI~Cf) ~ ~ Rti(RtUI 320 20 CR mlf 338 eii) ~ "$t CjulfjmSi ~ 1 ftl j c: IFl! Cf> Pc! Cf> Ift ~ fi'~~~~"1:rT1g=,<q:=rT1 342 2 ftljC:IFl!Cf> Pc!Cf>I"H ~ "1qltll·iGl 347 3 ftljC:IFl!Cf> Pc!Cf>lft ~-~ 351 4 "H IjC: 1Fl!Cf> Pc! cnl"H ~ ~lq9l'< 354 5 "H IjC:IFl!Cf> Pc!Cf>I"H