Evidence-Based Initiatives of FIAN Nepal on Right to Food Policies, Programmes & Practices in Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

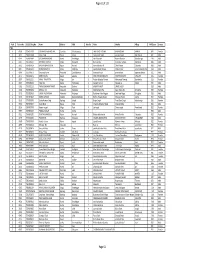

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Humla Mugu Jumla Kalikot Dolpa Karnali, Mugu Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

Hariyo Ban Program Ii Threats and Vulnerabilities

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM II (2016-2021) THREATS AND VULNERABILITIES ASSESSMENT OF PARKS AND CORRIDORS OF TERAI ARC LANDSCAPE Prepared by: WWF in partnership with CARE, FECOFUN and NTNC P.O. Box 7660 Kathmandu, Nepal 21 April 2017 © WWF 2017 All rights reserved Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part must mention the title and credit WWF. Published by WWF Nepal PO Box: 7660 Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal T: +977 1 4434820, F: +977 1 4438458 [email protected] , www.wwfnepal.org/hariyobanprogram Disclaimer This Threats and Vulnerabilities Assessment of Parks and Corridors in Terai Arc Landscape is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Contents INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................5 METHODOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................................6 Chitwan National Park and Buffer Zone ...................................................................................................................7 Threat Ratings of Chitwan National Park and Buffer Zone...................................................................................8 Barandabhar Corridor ........................................................................................................................................... -

Chapter – I Introduction

CHAPTER – I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Tourism is a multidimensional concept or activities which has been defined in different ways by various authors and concerned organizations and yet there is no universally accepted definition of tourism. The origin of tourism can be traced to the earliest period of human habitation on the globe. Tourism word derived from Latin word ‘Tornos’ means turners wheel or moving around and which is related to travelling in difference places. The concept of “round trip” or “package tour” is developed from the word Tornos or Tourism. It was generally started to use in 13th century but innovatively it was used after the 19th century in a wide-range. There are four different perspectives to comprehend tourism in detail. The Tourist: The tourist seeks various psychic and physical experiences and satisfactions. The nature of these will largely the destinations chosen and the activities enjoyed. Service provider Business people: Business people see tourism as an opportunity to make a profit by supplying the goods and services that the tourist market demands. The government of the host community or Area: Politicians view tourism as a wealth factor in the economy for their jurisdictions. Their perspective is related to the incomes their citizen can earn from their business. Politicians also consider the foreign exchange receipts from international tourism as well as the tax receipts collected from tourist expenditures, either directly or indirectly. The 1 government can play and important role in tourism policy, development, promotion and implementation. The Host community: Local people usually see tourism as cultural and employment factor of importance to the group, for example is the effect of the interaction between large number of international visitors and residents. -

Karnali Province Tourism Master Plan 2076/77 - 2085/86 BS (2020/21-2029/30)

Karnali Province Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment Surkhet, Nepal Karnali Province Tourism Master Plan 2076/77 - 2085/86 BS (2020/21-2029/30) January 2020 i Karnali Province Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment (MoITFE) Surkhet, Nepal, 2020 KARNALI PROVINCE TOURISM MASTER PLAN 2076/77 - 2085/086 BS (2020/21-2029/30) Technical Assistance WWF Nepal, Kathmandu Office, Nepal Consulting Services Mountain Heritage, Kathmandu, Nepal Advisors Hon. Nanda Singh Budha : Minister; Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment/Karnali Province Dr. Krishna Prasad Acharya : Secretary; Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment/Karnali Province Mr. Dhirendra Pradhan : Ex- Secretary; Ministry of Industry, Tourism, Forest and Environment/Karnali Province Dr. Ghana Shyam Gurung : Country Representative, WWF Nepal Mr. Santosh Mani Nepal : Senior Director, WWF Nepal Focal Persons Ms. Anju Chaudhary : MoITFE/Karnali Province Mr. Eak Raj Sigdel : WWF Nepal Planning Expert Team Members Ms. Lisa Choegyel : Senior Tourism Marketing Advisor Mr. Ram Chandra Sedai : Team Leader/Tourism Expert Dr. Roshan Sherchan : Biodiversity Expert Mr. Jailab K. Rai : Socio-Economist and Gender Specialist Er. Krishna Gautam : Environmental Engineer Mr. Harihar Neupane : Institutional and Governance Expert Mr. Yuba Raj Lama : Culture Expert Cover Photo Credit Ram C.Sedai (All, except mentioned as other's), Bharat Bandhu Thapa (Halji Gomba & Ribo Bumpa Gomba), Chhewang N. Lama (Saipal Base Camp), Dr. Deependra Rokaya (Kailash View Dwar), www.welcometorukum.org (Kham Magar), Google Search (Snow Leopard, Musk Deer, Patal Waterfall, Red Panda). ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Consultant Team would like to acknowledge following institutions and individuals for their meaningful contribution towards the formulation of Karnali Province Tourism Development Master Plan. -

Assessment of Poaching and Illegal Wildlife Trafficking in Banke- Kamdi Complex

Assessment of Poaching and Illegal Wildlife Trafficking in Banke- Kamdi Complex Submitted to: Hariyo Ban Program Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: People’s Help Group (PHG) Kathmandu, Nepal July, 2017 © WWF Nepal 2017 All rights reserved Disclaimer: This report is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents of this report are the responsibility of People’s Help Group (PHG) and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Executive Summary Wildlife crime is a serious issue in conservation particularly of the threatened species of wild flora and fauna globally. Several endangered species such as Asian big cats, elephants and rhinoceros are at the verge of extinction if the current trend of wildlife crime is not retarded. The illegal wildlife trade is among the leading causes for rapid wildlife species decline worldwide (McMurray, 2008). Similarly, Nepal cannot be exception to this situation; the country has been known as transit for illegal wildlife trade and a source for some of the illegally traded species such as rhino horns, tiger and leopard pelts and pangolin scales. Despite various efforts to control wildlife crime, such crime still exists sporadically and in low volume in the country. The Banke-Kamdi complex is located in the (Mid-western region, State No.6) and covers part of Banke, Dang and Salyan districts. This Complex comprises of Banke National Park (BaNP), its Buffer Zone and Kamdi forest corridor. At present, Kamdi Corridor is under the Banke District Forest and is one of the most important biological corridors of Tarai Arc Landscape. -

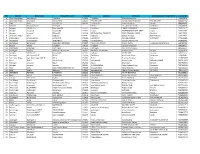

Devipatan Zone CSC List

Grampanchayat District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Contact No Village Name Bahraich Bahraich1 Hathiya Bojhi 271881 hathiya bojhi Farooq Ansari 7054482275 Bahraich Behriach Chittaura(R) 271801 Samsa tarhar Adarsh Kumar Gautam Samsa tarhar 7054693883 Bahraich Bahraich Nanpara 271865 chaugodwa nawabganj Arman Ahmad Chaugorwa 7081092832 Bahraich Bahraich Mahasi 271801 Saraswati nagar India Itech_Lait Kumar bajpaiMahasi 7275011100 Bahraich Vishveshwarganj Bhagirathpurwa Nethiya 271821 Bhagirathpurwa Nethiya VASUDEV PRASAD CHAUHAN 7275248043 Bahraich Nawabganj Umariya 271881 Umriya (Nandagaon) Shrawan Kumar Verma 7376126247 Bahraich Bahraich-NIELIT MIHINPURWA 271855 GANGAPUR AKHILESH PRATAP SINGH GANGAPUR 7376145900 Bahraich Behriach Balha(R) 271865 Sugar Factory, Nanpara Deepak Kumar Siletanganj 7376640895 Bahraich Jarwal Naraunda 271872 Naraunda Deepak kumar pal 7379293493 Bahraich Mihinpurwa Bojhiya 271855 Bojhiya Bazar OM PRAKASH 7379566421 Bahraich Behriach Mihipurwa(R) 271855 Madhwapur Om Prakash Madhwapur 7379568921 Bahraich Behriach1 Mihipurwa(R) 271855 Rampurwa Satish Kumar Rampurwa 7379892297 Bahraich Bahraich-NIELIT Bahraich 271801 Banhraich Asiya Begum Bahraich 7388238777 Bahraich Bahraich-NIELIT KAISERGANJ 271903 KAISERGANJ SATISH KUMAR SRIVASTAVADIHVASHER BAHADUR SINGH7398192862 Bahraich Bahraich Etawah 271865 Nanpara Azhar Ali SARAIYAN 7398196031 Bahraich Behriach Bahraich(U) 271801 Bahraich(U) Jaleel Ahmed Dargah Shareef 7398203894 Bahraich Huzoorpur Shivnaha 271872 Shivnaha Ritu srivastava Dewanpur -

RFP Documents Before the Proposal Submission Date

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL RFP 01 F/Y 2066/67 Monitoring and Evaluation of the Basic Telecommunication Service Licensee of license no:- Basic 03 (Nepal Satellite Telecom Pvt. Ltd) October 2009 RFA Selection of Consultant Basic-03 2/ 73 Section 1. Letter of Invitation Nepal Telecommunications Authority Bluestar Office Complex, Tripureshwor, Kathmandu Dear Mr./Ms 1. Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) invites proposals to provide the consulting services on Monitoring and Evaluation of the Basic Telecommunication Service Licensee of license no:- Basic 03 (Nepal Satellite Telecom Pvt. Ltd) with the objective to supervise the implementation of the Roll out Obligation of the Licensee. More details on the services are provided in the Terms of References . 2. A firm/consultant will be selected under Least Cost Selection (LCS) method and procedures described in this RFP 3. The RFP includes the following documents: Section 1 - Letter of Invitation Section 2 - Instructions to Consultants (including Data Sheet) Section 3 - Technical Proposal - Standard Forms Section 4 - Financial Proposal - Standard Forms Section 5 - Terms of Reference Section 6 - Standard Forms of Contract 4. Please inform us in writing at the following address before the closing date mentioned in this RFP (a) Whether you will submit a proposal alone or in association which shall be in the form of a Joint Venture with joint and several liabilities. 5. NTA reserves all rights to accept or reject any or all proposals without assigning any reason whatsoever. Yours sincerely, _____________________________ Mr. Bhesh Raj Kanel Chairman, Nepal Telecommunications Authority Date :- 5th November 2009 RFA Selection of Consultant Basic-03 3/ 73 Section 2. -

Mcpms Result of Lbs for FY 2065-66

Government of Nepal Ministry of Local Development Secretariat of Local Body Fiscal Commission (LBFC) Minimum Conditions(MCs) and Performance Measurements (PMs) assessment result of all LBs for the FY 2065-66 and its effects in capital grant allocation for the FY 2067-68 1.DDCs Name of DDCs receiving 30 % more formula based capital grant S.N. Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Palpa 90 150 2 Dhankuta 85 150 3 Udayapur 81 150 Name of DDCs receiving 25 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Gulmi 79 125 2 Syangja 79 125 3 Kaski 77 125 4 Salyan 76 125 5 Humla 75 125 6 Makwanpur 75 125 7 Baglung 74 125 8 Jhapa 74 125 9 Morang 73 125 10 Taplejung 71 125 11 Jumla 70 125 12 Ramechap 69 125 13 Dolakha 68 125 14 Khotang 68 125 15 Myagdi 68 125 16 Sindhupalchok 68 125 17 Bardia 67 125 18 Kavrepalanchok 67 125 19 Nawalparasi 67 125 20 Pyuthan 67 125 21 Banke 66 125 22 Chitwan 66 125 23 Tanahun 66 125 Name of DDCs receiving 20 % more formula based capital grant S.N Name PMs score Rewards to staffs ( Rs,000) 1 Terhathum 65 100 2 Arghakhanchi 64 100 3 Kailali 64 100 4 Kathmandu 64 100 5 Parbat 64 100 6 Bhaktapur 63 100 7 Dadeldhura 63 100 8 Jajarkot 63 100 9 Panchthar 63 100 10 Parsa 63 100 11 Baitadi 62 100 12 Dailekh 62 100 13 Darchula 62 100 14 Dang 61 100 15 Lalitpur 61 100 16 Surkhet 61 100 17 Gorkha 60 100 18 Illam 60 100 19 Rukum 60 100 20 Bara 58 100 21 Dhading 58 100 22 Doti 57 100 23 Sindhuli 57 100 24 Dolpa 55 100 25 Mugu 54 100 26 Okhaldhunga 53 100 27 Rautahat 53 100 28 Achham 52 100 -

Sno District Block Name Village/CSC Name Pincode Location VLE Name Grampanchayat Village Name Contact No 1 Sant Kabir Nagar Semr

SNo District Block Name Village/CSC name Pincode Location VLE Name Grampanchayat Village Name Contact No 1 Sant Kabir Nagar Semriyawan Tekensha 272125 Tekensha Mohammad Azam 789660973 2 Sant Kabir Nagar S K nagar3 MEHDAWAL 272271 PACHNEVARI ASHOK KUMAR MISHRA PACHNEVARI 840040772 3 Mau MAU RATANPURA 121705 Haldhar Pur Brijesh chauhan Ratohi 888069301 4 Varanasi Varanasi-NIELIT chollapur LANKA CIC_Manish Pandey Chollapur 896088439 5 Jaunpur JAUNPUR5 Ram nagar(R) 222137 Jamalapur LAXMI CHAURASIA Jamalapur 900559551 6 Jaunpur Jaunpur6 Jaunpur(R) 222139 Lapari MOHAMMAD AJMAL SHAH Lapari 904471787 7 Jaunpur Jaunpur1 Sirkoni(R) 222138 DR SHYAMLAL PRAJAPATI GYAN PRAKASH YADAV Gaddipur 964290095 8 Ambedkar Nagar Bhiti Naghara 224141 Naghara Gunjan Pandey Balal Paikauli 979214477 9 Maharajganj Maharajganj2 LAXMIPUR 273164 LAXMIPUR RAMESH KUMAR SURYAPUR 979416162 10 Gorakhpur Kempiyarganj Jangal Bihuli 273001 JUNGLE BIHULI SANJAY SRIVASTAVA 979456745 11 Gorakhpur Gorakhpur Jungle Beni Madho(U) 273007 Neaer Shiv Mandir Brijesh Kumar Jungle Beni Madho No.2 980792705 12 Deoria Bhatni Singhpur 274705 Singhpur Ugrasen Chaurasia 984188375 13 Chitrakoot Ramnagar Ram Nagar 245856 ramnagar Ravi Shanker Gupta 985632647 14 Azamgarh Koyalsa Molnapur Nathnpatti 246141 Molnapur Nathnpatti Ramesh Yadav Pasipur 993605118 15 Jaunpur JAUNPUR4 Barsathi(R) 222162 Ojhapur SUJIT PATEL Jarauta 994245307 16 Mirzapur Mirzapur-NIELIT Sikhar 231306 Pachranw Atul Kumar Singh pachranw 995695683 17 Sant Kabir Nagar Sant Kabir Nagar-NIELIT Belrai 451586 Belrai Pradeep Srivastav -

CEDAW) 58Th Session, June 2014

Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) 58th session, June 2014 Fourth and Fifth Review – India THE RIGHT TO ADEQUATE FOOD OF WOMEN IN INDIA Submitted by FIAN India 1. HUNGER AND MALNUTRITION IN INDIA As per the State of Food Insecurity in the World1, India remains home to the largest number of undernourished people in the world: 213 million (17% of its population) between 2011 and 2013. Considering various poverty norms, about 75% of the Indian population suffers from hunger and malnutrition to varying degrees, 50% of it acutely. The Global Hunger Index (GHI) ranks India at 63 with a score of 21.3 among 120 countries, classifying its situation as within the ‘alarming’ category2. The report also noted that India continued to record one of the highest prevalences of children under five who are underweight, at more than 40%, and is among the countries with the highest prevalence of anemia, which affects 51% of women in the age bracket of 15-59 years and 87% of pregnant women. More than 70% of Indian women and children have serious nutritional deficiencies. Similarly, the level of adult malnutrition is high, affecting one-third of the country’s adults. In this regard, Scheduled Tribes (STs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), and minorities (Muslims) are at a great disadvantage. As per India’s State Hunger Index (ISHI), 12 of the 17 states surveyed fall into the ‘alarming’ category and one into the ‘extremely alarming’ category. These 17 major states comprise 95% of total population of India3. About 68.84% of the population of India is rural, the majority of whom greatly suffers from hunger and malnutrition. -

District Transport Master Plan (DTMP)

Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Mugu VOLUME I: MAIN RPEORT April, 2013 Prepared by Rural Infrastructure Developers Consultants (RIDC) P.Ltd, Kathmandu for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office (DTO), Mugu with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID FOREWORD i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We would like to express gratitude to RTI SECTOR Maintenance Pilot for entrusting us on preparation of District Transport Master Plan of Mugu District. We would also like to express our sincere thanks to Mr. Bharat Gautam, LDO and Er. Bir Bahadur Rawal, DTO of Mugu District for their cooperation and coordination during DTMP preparation. We would also like to thank the concerned officials and staffs from DDC for their support during the DTMP workshops. We thank the expert team who has worked very hard to bring this report at this stage and successful completion of the assignment. We are grateful to the VDC secretary from all VDCs, local people, political parties and leaders, members of government organizations and non government organizations of Mugu District who have rendered their valuable suggestion and support for the successful completion of the DTMP work. Rural Infrastructure Developers Consultants P. Ltd. (RIDC), Baneshwor, Kathmandu. ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mugu District is located in Karnali Zone of the Mid-western Development Region of Nepal. It borders with Dolpa district of Karnali to the East, Bajura district of Seti Zone to the West, Humla of Karnali Zone and Tibbet of People Republic of China to the North and Kalikot and Jumla of Karnali Zone to the South.