Covid-19 Survey Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Dakota’S Official State Jewelry

* Stay on one hotel! Unpack only once…. * Mount Rushmore ‐ including nighme lighng ceremony! Badlands Naonal Park * Crazy Horse Memorial * Devils Tower Naonal Monument * Custer State Park * Deadwood Day 1: Fly Hartford/Bradley to Rapid City, SD. Welcome to Trail around the base of the monument -OR- explore the exhibits Rapid City, long known as the gateway to the Black Hills. at the visitor’s center to learn about the natural and cultural Welcome dinner featuring a Native American chronicler who history of the park. While it was made famous as the backdrop in shares stories about the Lakota & Sioux way of life. (D) Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the tower is sacred to many Northern Plains tribes. (B, D) Day 2: Learn the history of some enterprising Westerners during a visit to the Chapel in the Hills. Then, visit Crazy Horse Day 5: Learn more about Black Hills gold on a tour through Memorial & learn the story behind the world’s largest, still-in- Riddle’s Black Hills Gold & Diamond Factory. Watch skilled progress mountain sculpture. The memorial includes the Indian artisans handcraft South Dakota’s official state jewelry. Time to Museum of North America, the Native American Cultural Center, shop for some unique items. The Needles Highway is calling the sculptor’s studio, orientation center and theaters. Next, head your name. Travel through 14 miles of magnificent rock for mighty Mount Rushmore to spend some time with the epic formations, curving tunnels and steep spires. We continue our figures of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt and Lincoln as you road trip through Custer State Park where you just might spot stroll along the Presidential Trail that offers the closest access to a buffalo, a band of bighorn sheep or a herd of majestic elk. -

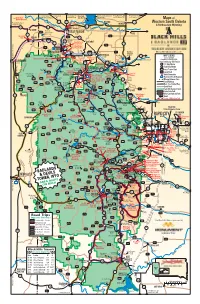

2010 Black Hills

From Broadus, Belle Fourche Reservoir From Bowman, ND From Faith, SD Z From Buffalo, SD Rocky Point Devils Tower Custer Battlefield, MT From Medora, ND State Rec. Area Orman Dam From Dickinson, ND From Lemmon, SD National Monument Belle Fourche 212 85 212 From Devils Tower, Wyo River Tri-State Museum NEWELL From Hulett, Wyo 22 BLACKBLACK ? Center of the Nation 212 NISLAND 24 34 Monument 10 Belle Fourche ALADDIN McNenny River Fish Hatchery BELLE FOURCHE 543 EL3017 VALE HILLS Mirror Lake HILLS 111 10 20 BEULAH 21 34 17 && BADLANDSBADLANDS 19 ? 2 90 85 ST. ONGE 14 8 205 10 79 D.C. Booth 18 ofSouth Dakota 10 12 Historic Fish Hatchery 19 ? & Northeastern Wyoming 14 17 SPEARFISH 23 3 EL3657 90 Bear Butte WHITEWOOD Bear Butte State Park MAP LEGEND From Devils Tower, Wyo Tower, From Devils 863 34 Crow Peak EL3648 Lake Copyright © 2010 by BHB&L 14A High Plains Western Computer generated by BHB&L 134 30 ? SUNDANCE 130 Citadel Spearfish Heritage Center Bear Butte Creek 112 EL4750 Rock STURGIS Interchange Exit Number Byway Peak 85 14 EL3450 14 U.S. Hwy. Marker 214 195 Broken Boot 8 6 Scenic Bridal Gold Mine 44 State Hwy. Marker Veil Falls Mt. Theo ? Ft. Meade Iron Creek Black Hills Roosevelt DEADWOOD 14A 32 21 Forest Service Road Grand Canyon Canyon Lake Canyon Mining Sturgis Motorcycle Museum Moskee Hwy. Little 133 12 18 County Road Crow Peak Museum 4 Boulder & Hall of Fame 141 Cement Ridge 34 ? Visitor Information Lookout 134 19 CENTRAL CITY Adams Museum & House Spearfish ? ? Gulches of Fun 170 7 Mileage Between Stars 103 222 Spearfish LEAD EL5320 SAVOY Falls PLUMA Amusement Park 170 Black Hills 79 37 Paved Highway 807 3 National 850 Roughlock 385 Cemetery Multi-Lane Divided Hwy. -

Map of the Hills

From Broadus, - Little Bighorn From Buffalo, SD Belle Fourche Reservoir From Bowman, ND From Faith, SD Z Rocky Point Devils Tower Battlefield and Alzada, MT and Medora, ND State Rec. Area Orman Dam and Dickinson, ND and Lemmon, SD National Monument Belle Fourche River 212 J 85 212 From Devils Tower Tri-State Museum NEWELL and Hulett, Wyo 22 BLACK ? Center of the Nation 212 NISLAND 24 34 Monument 10 Belle Fourche ALADDIN McNenny River 543 Fish Hatchery BELLE FOURCHE Mirror Lake EL3021 VALE HILLS 111 10 20 21 34 BEULAH 17 & BADLANDS 90 19 ? 2 85 Spearfish Rec & ST. ONGE 14 8 Aquatic Center 79 205 10 18 D.C. Booth Historic ofSouth Dakota 10 12 19 Nat’l Fish Hatchery & Northeastern Wyoming ? 14 17 SPEARFISH J 23 3 EL3645 90 Bear Butte 863 WHITEWOOD Bear Butte State Park 34 MAP LEGEND Crow Peak EL3654 Lake From Devils Tower, Wyo Tower, From Devils Termeshere Gallery & Museum Tatanka Story of ©2018 by BH&B 134 14A High Plains Western the Bison Computer generated by BH&B Citadel 30 Bear Butte Creek ? SUNDANCE 130 Spearfish Heritage Center Boulder Canyon 112 EL4744 Rock Peak 85 14 STURGIS Interchange Exit Number Byway Golf Club at EL3421 14 U.S. Hwy. Marker 214 195 Broken Boot 8 6 J Bridal Apple Springs 44 Scenic Veil Falls Gold Mine State Hwy. Marker Mt. Theo DEADWOOD ? Iron Creek Black Hills Roosevelt 14A Canyon 32 Ft. Meade Old Ft. Meade 21 Forest Service Road EL4537 Grand Canyon Lake Mining Museum Canyon Little 133 12 Moskee Hwy. 134 Boulder 18 Crow Peak Museum 4 County Road Adventures at Sturgis Motorcycle 141 Cement Ridge Museum 170 34 ? Visitor Information Lookout Spearfish 19 CENTRAL CITY Days of 76 Museum Canyon Lodge Spearfish ? ? & Hall of Fame Bikers 7 Mileage Between Stars 222 Spearfish Historic LEAD 103 Falls Homestake EL5203 Adams Museum & House 170 Black Hills Scenic SAVOY PLUMA 79 37 Byway Paved Highway 807 Opera House 3 National Dwd Mini-Golf & Arcade 18 Cemetery Multi-Lane Divided Hwy. -

Stave Churches Are Unique to Norway. It Is Considered the "Most Important Example of Wooden Medieval Architecture in Europe." a Stave Church Is Made Entirely of Wood

Stave churches are unique to Norway. It is considered the "most important example of wooden Medieval architecture in Europe." A stave church is made entirely of wood. Poles ("staver" in Norwegian) has given it its name. Most of the churches were built before 1350, but most did not survive since the supporting timber was placed directly into the ground and experienced rot and collapsed in time. <fjordnorway.com> The construction involved columns, planks and supports that were joined by dovetailing pegs and wedges with glue or nails. In the source, <ingebretsens.com> a thorough review of history and construction can be read. Stave churches have fine detail with a combination of Christian designs and pre‐Christian Viking themes with animals and dragons. It is believed that Norway had over one thousand churches. That number has dwindled to less than 25 today. The one we visited in Bergen, Norway can be viewed on acuri.net. The church in Rapid City is a replica of the Borgund stave church built in 1180 and was dedicated to the Apostle Andrew in Laerdal, Norway. It is still well preserved. From the <Chapel‐in the‐Hills> website, we learn the following about the history of this church: "It is the result of a dream of one man and the generous support of another...In the 1960's, the originator and preacher of the Lutheran Vespers radio hour, Dr. Harry R. Gregerson, was looking to expand the scope of his popular radio ministry. As his dream took shape, Dr. Gregerson realized there was the perfect location for his facility right in his own state of South Dakota in the Black Hills. -

NATIONAL PARKS, NATURALLY! Mountains, Monuments, Memorials!

NATIONAL PARKS, NATURALLY! Mountains, Monuments, Memorials! with Women of the Midwest W! ! & M)%& Travel Solo Together June 9-17, 2021 CO | IA | KS | MN | MO | NE Dear Women of the Midwest, Mother Nature took her time when she went to work on America’s most dramatic natural playground; Yellowstone. The myriad sights guarantee us days of thrills as we experience Old Faithful Geyser, a part of Upper Geyser Basin which contains at least 150 gushers, Yellowstone Lake, and Yellowstone Canyon. But Yellowstone National Park is not the only highlight of our tour! Through a colorful journey, we will experience the “Wonders of the West” as we travel through stunning scenery, admire the herds of bison, elk, Rocky Mountain goat, mule, deer, and listen to the roar of the waters. We will visit Mt. Rushmore and the astounding monument of four Presidents, Crazy Horse Memorial, built in honor of the Lakota Chief, and drive through the Black Hills National Forest with its timbered mountains, rugged rock formations, canyons, grasslands, streams, and lakes, which are only a few of the highlights. Journal Star Destinations We will listen to stories of Buffalo Bill and Jane Calamity, feel the power of the sacred site of Devil’s Tower, and unwind in the cowboy-town of Jackson after touring Grand Teton National Park. At the end of the trip, you may even dip your toes in Bear Lake’s turquoise-blue water! One grand overlook after the other, that’s what awaits on this spectacular journey, so come, join me, solo or two-by-two. -

2020 BH&B Tear-Off Map .Indd

Z From Broadus, - Little Bighorn From Buffalo, SD Rocky Point Belle Fourche Reservoir From Bowman, ND From Faith, SD Devils Tower Battlefield and Alzada, MT and Medora, ND State Rec. Area Orman Dam and Dickinson, ND and Lemmon, SD National Monument Maps of Belle Fourche River 212 NISLAND Western South Dakota From Devils Tower 85 Tri-State Museum NEWELL 212 and Hulett, Wyo 22 & Northeastern Wyoming 24 34 ? Center of the Nation 212 10 Monument Belle Fourche River N ALADDIN McNenny 543 Fish Hatchery BELLE FOURCHE Mirror Lake 10 EL3021 VALE Vore Buffalo 111 20 Jump BEULAH 21 34 Lookout 17 ? Mountain 19 2 90 85 EL4452 Spearfish Rec & ST. ONGE 205 14 8 10 Aquatic Center 79 D.C. Booth Historic 18 12 19 10 Nat’l Fish Hatchery ? 14 17 SPEARFISH 23 3 Bear Butte BlackHillsBadlands.com EL3645 90 State Park Crow Peak WHITEWOOD Bear Butte EL 4426 863 EL 5780 EL3654 34 MAP LEGEND From Devils Tower, Wyo Tower, From Devils Lake Termesphere Gallery & Museum Tatanka Story of ©2020 by BH&B 14A High Plains Western the Bison Bear Butte Creek Computer generated by BH&B 134 30 ? SUNDANCE 130 Citadel Spearfish Heritage Center 112 Interchange Exit Number EL4744 Rock Boulder Canyon STURGIS Byway Peak 85 14 Golf Club at EL3421 14 U.S. Hwy. Marker 214 Outlaw 8 Apple Springs 6 Bridal 195 44 Scenic Square State Hwy. Marker Veil Falls ? Ft. Meade Iron Creek Mt. Theodore DEADWOOD anyon 21 Forest Service Road Roosevelt 14A C 32 Grand Canyon Lake Broken Boot EL4537 Canyon Little Moskee Hwy. -

Discover South Dakota June 24 – 30, 2022

Central Bank's Classic Club presents… Discover South Dakota June 24 – 30, 2022 Book Now & Save $100 Per Person SPECIAL TRAVEL PRESENTATION Date: Thursday, April 29, 2021 Time: 1:00 PM Central Theatre, 111 N State Street, Geneseo, IL 61254 For more information contact Amber Thomas Central Bank's Classic Club (309) 944-1635 [email protected] Day 1: Friday, June 24, 2022 Rapid City, South Dakota - Tour Begins Welcome to the West. Your tour opens in Rapid City, long known as the gateway to the Black Hills. Tonight, you and your fellow travelers gather for a welcome dinner featuring a Native American chronicler who shares stories about the Lakota and Sioux way of life. (D) Day 2: Saturday, June 25, 2022 Rapid City - Crazy Horse - Mt. Rushmore - Rapid City Learn the history of enterprising Westerners at the Chapel in the Hills. Visit Crazy Horse Memorial and delve into the story of the largest, still-in-progress mountain sculpture. Visit the Indian Museum of North America, the Native American Cultural Center, the sculptor’s studio, orientation center and theaters. Continue to Mount Rushmore. Spend time with the epic figures of Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln as you stroll along the Presidential Trail, offering the closest view of this iconic sculpture. This evening, return to Mount Rushmore for the nighttime lighting ceremony.* (B) Day 3: Sunday, June 26, 2022 Rapid City - Badlands - Wall - Rapid City Embrace the allure of wide-open spaces and explore the larger-than-life Badlands National Park. At the visitor center, the stage is set for your adventure, with informative exhibits, displays and video to introduce you to the area. -

Rapid City Historic Preservation Commission

version JULY 12, 2020 Rapid City Historic Preservation Commission Phase II: Thematic Framework for Cultural Resource Inventory “Our History, Our Future: An Updated Historic Context Document for the Rapid City Historic Preservation Commission (2020)” Project Overview In 2019, the Rapid City Historic Preservation Commission (RCHPC) engaged Vantage Point Historical Services, Inc. (VPHS) to update its Comprehensive Plan and Historic Context Document. Across the country, historic preservation commissions use these documents to organize information about historical and cultural resources into a narrative that identifies themes and property types to help communities make decisions about how to use, learn from, and preserve local history. Phase I of this project included a planning retreat that resulted in draft updates to the RCHPC’s mission statement and strategic plan, its Comprehensive Plan and Historic Context Document, including a chronological “Overview of Rapid City’s History” that identified important eras in the city’s past. The Commission also held two community outreach sessions to engage a diverse set of Rapid City’s residents and solicit their feedback. Phase II includes the development of this thematic framework, which builds on the chronological narrative in the Historic Context Document. The framework describes Rapid City’s environmental setting and illuminates three major themes and various subthemes that give meaning and structure to the history of the community. Public feedback on these themes was provided in a workshop in June, 2020. In this phase, the project team also identified representative property types (sites and structures) closely associated with the themes and subthemes in the framework and created various maps associated with the themes and the representative property types. -

VIP Corporate Offers

2021 CORPORATE PARTNER VIP TRAINING PROGRAM The training card you have received encourages and enables VIPs, like you, to become better acquainted with local tourism businesses in the Black Hills and Badlands region. We hope you use your VIP Training Card to visit and enjoy as many member businesses as you can. Your knowledge and firsthand experience at our member businesses are an asset to both the visitor industry and visitors. Since this is a training program, we ask that you visit early in the season. Present your VIP Training Card this summer at participating BH&B member businesses and receive the following offers and special deals. Visit BlackHillsBadlands.com/VIPCards for more member to member offers. 1880 TOWN- SOUTH DAKOTA'S ORIGINAL FREE admission for cardholders. PRAIRIE HOMESTEAD HISTORIC SITE FREE admission for cardholder. 1881 COURTHOUSE MUSEUM FREE admission for cardholder. Valid May 24- Sept 30, 2021. PUTZ N GLO BLACK LIGHT MINIATURE GOLF 1/2 price admission for cardholder. Valid ADAMS HOUSE $2 off admission for cardholder. until Labor Day. AKELA SPA OF DEADWOOD 1/2 price Akela Garden for cardholder. REPTILE GARDENS FREE admission for cardholder. Return and visit as often as you'd like. BADLANDS HELICOPTERS 10% off tours #1-4 for cardholder. Reservations suggested. ROCKIN’ R TRAIL RIDES One 1/2 price 1-hour trail ride per year for cardholder. Reservations required. Call 605-673-2999. BEAR COUNTRY U.S.A. FREE admission for cardholder only. Not valid for special events. RUSH MOUNTAIN ADVENTURE PARK One FREE ride on each attraction (Soaring Eagle BELLE JOLI WINERY SPARKLING HOUSE One FREE wine tasting per year for cardholder. -

A Historic Context Document for Rapid City, South Dakota

Our History, Our Future: A Historic Context Document for Rapid City, South Dakota Figure 1: New construction intermingles with the forest on the hillside above Canyon Lake Park. Prepared for the Rapid City Historic Preservation Commission By Eric Steven Zimmer, PhD and Eric John Abrahamson, PhD Vantage Point Historical Services, Inc. with Brenna Maloney, MS, MA PENULTIMATE DRAFT April 2021 Acknowledgement of Grant Funding This program receives Federal financial assistance from the National Park Service. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the American With Disabilities Act of 1990, and South Dakota law SDCL 20-13, the State of South Dakota and U. S. Department of the Interior prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, sex, disability, ancestry or national origin. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: South Dakota Division of Human Rights, State Capital, Pierre, SD 57501, or the Office of Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 201 I Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. Figure 2: The sign at the Baken Park shopping plaza and Dinosaur Hill reflect the centrality of retail trade and tourism to the economic history of Rapid City. Rapid City Historic Preservation Commission 2 Historic Context Document – April 2021 Table of Contents List of Figures 5 Section A. Executive Summary 6 Section B. Introduction 8 - Project Overview and Methodology 10 - How to use this document 10 Section C: Environmental and Community Profile 13 - Environmental profile 13 - Contemporary Community Profile 16 Section D. -

Black Hills & Badlands

Santa Ana College Community Services Program Presents.... BLACK HILLS & BADLANDS SINGLE-HOTEL STAY FEATURING MT. RUSHMORE, BADLANDS, CUSTER STATE PARK & CRAZY HORSE AUGUST 23-28, 2013 ~ 6 DAY TOUR Via TOUR PACE ACTIVITY LEVEL Leisurely On the Go Low High ~DAY BY DAY ITINERARY~ Embark on a journey highlighting some of the West’s DAY 2 ~ BLACK HILLS, MT. RUSHMORE TOUR HIGHLIGHTS most famous sites and monuments. Wonder at the Following an included breakfast at our hotel, Visit Mount Rushmore National Memorial magnificent Mt. Rushmore and Crazy Horse memo- we’ll join our local guide for sightseeing that Visit Wall Drug and Badlands National Park rials. Enjoy the Wild West atmosphere of Deadwood, will include many of the most well-known and Visit the Crazy Horse Memorial – eventually and marvel at the spectacular landscape at Badlands well-liked highlights of the area. A visit to the to be the largest statue in the world National Park. All-the-while, unpack once and Journey Museum takes you on an incredible enjoy a single-hotel stay in the heart of Rapid City. trek through time, from the violent upheaval Visit Custer State Park for a buffalo safari jeep that formed the mystical Black Hills over 2.5 ride and dinner at the State Game Lodge billion years ago to the continuing saga of the Ride on a steam train through the Black Hills Western Frontier. When your journey is com- Guided tours of the Black Hills Mining plete, you will fully understand the legacy of Museum and Black Hills Gold Factory the land and its people. -

The Great Buffalo Roundup of the Black Hills Featuring Mount Rushmore, Crazy Horse and Deadwood

Wade Tours The Great Buffalo Roundup of the Black Hills featuring Mount Rushmore, Crazy Horse and Deadwood Departure Date: September 27, 2022 the town, see the local street shows and enjoy an included dinner Deadwood at the Silverado Casino. Meals: B, D DAY 3 1880 Train, Mount Rushmore and Journey Museum: Rapid City This morning board the 1880 Train of the Black Hills Central 5 Railroad for the1 spectacularOvernight mountain scenery found along the Wall tracks laid in the 1880sVisit to service the area mines. Enjoy free time for shopping in the rugged town of Keystone. Then pay a visit Crazy Horse Badlands Tour Route Keystone National Park to the famed Shrine of Democracy, Mount Rushmore National Custer State Park Memorial. See the memorial and explore the museum. Later, take SOUTH DAKOTA a drive through Bear Country USA Wildlife Park to see the many bears, wolves and elk found here. Return to Rapid City for an 1 Hotel Overnights included dinner. Meals: B, D Visit Hot Springs The Great Buffalo Roundup and Mammoth Site: Our day Tour Route DAY 4 starts early in Custer State Park with a pancake breakfast to get ready for the Great Buffalo Roundup. Each fall the ground rumbles and the dust flies as cowboys and park crews saddle up to bring DAY 1 Arrive in South Dakota: Your northwesterly journey begins in the thundering herd of nearly 1,300 strong. After an included in Rapid City. Meet your Tour Manager at 6:00 p.m. for dining lunch at the State Game Lodge, travel to Hot Springs, home to suggestions.