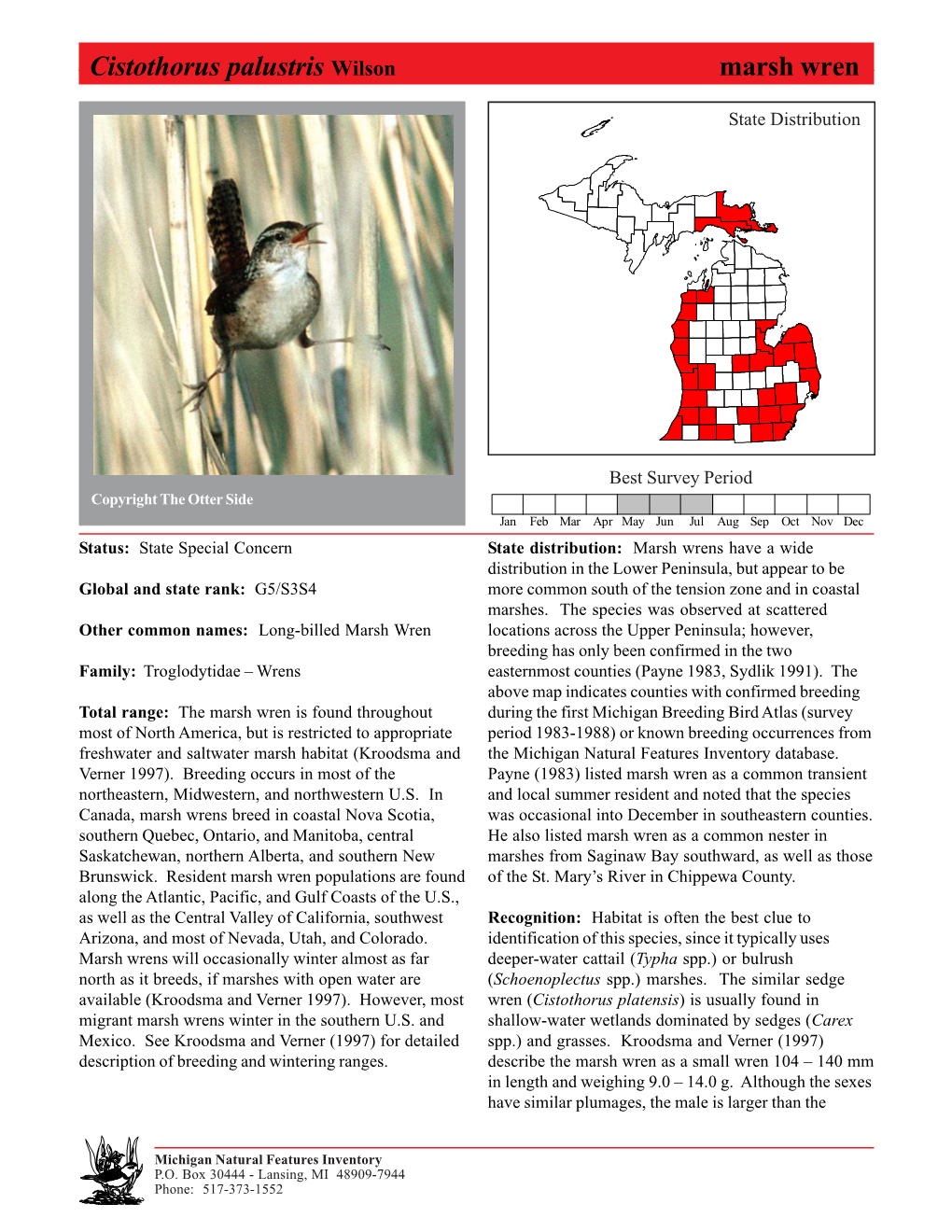

Cistothorus Palustris Wilson Marsh Marsh Wren, Wren Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature Notes from Kankakee Sands

Nature Notes from Kankakee Sands April 2019 © Jeff Timmons Where There’s a Willow, There’s a Way written by Alyssa Nyberg, Restoration Ecologist for The Nature Conservancy’s Kankakee Sands Project I was standing out in a 400-acre wet prairie just north of our Kankakee Sands office, placidly harvesting seeds when I hear the crackling, sizzling Zzzzap! like the sound of an electrical circuit shorting out. With exactly zero electric lines running through that particular prairie, what could have made that sound? Then I noticed a large willow patch… and where there is a willow patch at Kankakee Sands, there may be a sedge wren (Cistothorus platensis) singing its electrical sounding song. Sedge wrens are a rare treat to see and hear, because they are a shy and skittish bird. Unlike the chatty, boisterous, easily-viewed house wren, the sedge wren avoids being seen. Even when frightened, the sedge wren will rarely take flight. Instead, it will run on the ground beneath vegetation. It may take flight, but only briefly, before fluttering to the ground to escape notice. The sedge wren is an even more exciting find because it is state endangered in Indiana. Habitat loss and conversion are the main causes of its decline. However, at Kankakee Sands we have many acres of suitable, wet habitat with plenty of willows. And where there are willows, there is a way for the sedge wren to feed, mate, nest and raise young. Thanks to the restored habitat at Kankakee Sands, we get to enjoy its song during the months of April through October each year. -

Supplemental Information for the Marian's Marsh Wren Biological

Supplemental Information for the Marian’s Marsh Wren Biological Status Review Report The following pages contain peer reviews received from selected peer reviewers, comments received during the public comment period, and the draft report that was reviewed before the final report was completed March 31, 2011 Table of Contents Peer review #1 from Tylan Dean ................................................................................... 3 Peer review #2 from Paul Sykes.................................................................................... 4 Peer review #3 from Sally Jue ....................................................................................... 5 Peer review #4 from Don Kroodsman ........................................................................... 9 Peer review #5 from Craig Parenteau ........................................................................ 10 Copy of the Marian’s Marsh Wren BSR draft report that was sent out for peer review ........................................................................................................................... 11 Supplemental Information for the Marian’s Marsh Wren 2 Peer review #1 from Tylan Dean From: [email protected] To: Imperiled Cc: Delany, Michael Subject: Re: FW: Marian"s marsh wren BSR report Date: Thursday, January 27, 2011 10:38:25 PM Attachments: 20110126 Dean Peer Review of Draft Worthington"s Marsh Wren Biological Status Review.docx 20110126 Dean Peer Review of Draft Marian"s Marsh Wren Biological Status Review.docx Here are both of my -

First Documented Observation of Sedge Wren in Arizona Accepted

Arizona Birds - Journal of Arizona Field Ornithologists Volume 2011 FIRST DOCUMENTED OBSERVATION OF SEDGE WREN (Cistothorus platensis) IN ARIZONA Alan Schmierer, PO Box 626, Patagonia, AZ 85624 ([email protected]) Photos by the author. On 27 November 2010 the author discovered and photographed a Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis) on the shores of Peña Blanca Lake, Santa Cruz County, Arizona. This sighting was the first documented record of this species for Arizona. INITIAL DISCOVERY AND CONTINUED SIGHTINGS The initial discovery of this bird was a very brief encounter. At about mid-morning I was birding the south shore of the cove (informally called Thumb Rock Cove; see Figure 2) that is just north of the Upper Thumb Rock Picnic Area parking lot. Several double-chip notes, some- what reminiscent of those of the Pacific and Winter Wrens (Troglodytes pacificus and heimalis) alerted me to a potentially interesting bird be- ing present, followed by a 15 second look at the bird with binoculars (at about a two meter dis- tance), two quick photos (a lesson for photogra- phers to keep their cameras handy for such “bird emergencies”) and then the bird was gone. The wren was seen while it was about 1.5 m up in bare branches close to the trunk of a small deciduous tree at the water’s edge, and it then flew across the cove to a grassy edge of the op- posite shore. That brief view was enough for me to identify it as a Sedge Wren. Even as a new- comer to Arizona I knew that it was likely a very Figure 1: SEDGE WREN (27 November 2010) at initial sighting. -

B a N I S T E R I A

B A N I S T E R I A A JOURNAL DEVOTED TO THE NATURAL HISTORY OF VIRGINIA ISSN 1066-0712 Published by the Virginia Natural History Society The Virginia Natural History Society (VNHS) is a nonprofit organization dedicated to the dissemination of scientific information on all aspects of natural history in the Commonwealth of Virginia, including botany, zoology, ecology, archaeology, anthropology, paleontology, geology, geography, and climatology. The society’s periodical Banisteria is a peer-reviewed, open access, online-only journal. Submitted manuscripts are published individually immediately after acceptance. A single volume is compiled at the end of each year and published online. The Editor will consider manuscripts on any aspect of natural history in Virginia or neighboring states if the information concerns a species native to Virginia or if the topic is directly related to regional natural history (as defined above). Biographies and historical accounts of relevance to natural history in Virginia also are suitable for publication in Banisteria. Membership dues and inquiries about back issues should be directed to the Co-Treasurers, and correspondence regarding Banisteria to the Editor. For additional information regarding the VNHS, including other membership categories, annual meetings, field events, pdf copies of papers from past issues of Banisteria, and instructions for prospective authors visit http://virginianaturalhistorysociety.com/ Editorial Staff: Banisteria Editor Todd Fredericksen, Ferrum College 215 Ferrum Mountain Road Ferrum, Virginia 24088 Associate Editors Philip Coulling, Nature Camp Incorporated Clyde Kessler, Virginia Tech Nancy Moncrief, Virginia Museum of Natural History Karen Powers, Radford University Stephen Powers, Roanoke College C. L. Staines, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center Copy Editor Kal Ivanov, Virginia Museum of Natural History Copyright held by the author(s). -

House Wren Nest-Destroying Behavior’

The Condor 88:190-193 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1986 HOUSE WREN NEST-DESTROYING BEHAVIOR’ JEAN-CLAUDE BELLES-ISLES AND JAROSLAV PICMAN Department of Biology, Universityof Ottawa, Ottawa KIN 6N5, Canada Abstract. House Wren (Troglodytesaedon) nest-destroying behavior was studied by experi- mentally offering 38 wrens nestswith eggs(or nestlings)throughout the nesting season.Individuals of both sexespecked all six types of eggspresented, regardless of the nest type and location. House Wrens also attacked conspecificyoung. Older nestlings(nine days old) were less vulnerable than three-day-old young. Our resultssuggest that nest-destroyingbehavior is inherent in all adult House Wrens but is inhibited in mated males and breeding females. It is suggestedthat nest destruction may have evolved as an interference mechanism reducing intra- and interspecific competition. Key words: House Wren; Troglodytes aedon; infanticide;nest destruction; competition. INTRODUCTION specificnestlings? (3) Is this behavior exhibited Destruction of eggs by small passerinesis a throughout the breeding season?(4) Do indi- relatively rare phenomenon which has been vidual House Wrens destroy neststhroughout observed mainly in members of two families, their breeding cycle? (5) How widespread is the Troglodytidae and Mimidae. Species this behavior among individuals from a pop- known to destroy eggsinclude the Marsh Wren ulation? (6) Is this behavior a local phenom- (Cistothoruspalustris; Allen 19 14); House enon or is it characteristic of all House Wren Wren (Troglodytesaedon; Sherman 1925, populations?(7) What is the adaptive value of Kendeigh 194 1); Cactus Wren (Campylorhyn- this behavior? thusbrunneicapillus; Anderson and Anderson METHODS 1973); SedgeWren (Cistothorusplatensis; Pic- man and Picman 1980); Bewick’s Wren This study was conducted at Presqu’ile Pro- (Thryomanesbewickii; J. -

Breeding Biology of the Long-Billed Marsh Wren

Vol. 67 BREEDING BIOLOGY OF THE LONG-BILLED MARSH WREN BY JARED VERNER Although much of the life history of the Long-billed Marsh Wren (Telmatodytes pulustris) has been described (see especially Welter, 1935 ; Bent, 1948; and Kale, MS), most aspects have not been quantified adequately to permit analysis of geo- graphical variation between populations, Such variation often leads to insights into the ecology of a species which would otherwise be impossible. This paper presents comparative data on birds from two populations in Washington State, one (T. p. paludicola) at Seattle, the other (T. p. plesius) at Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge, 15 miles south of Spokane and 22.5 miles due east of Seattle (fig. 1). Other aspects of this study are treated elsewhere (Verner, 1964; also MS, 1963). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is a pleasure to acknowledge the numerous helpful suggestions and criticisms of Drs. Frank Richardson and Gordon H. Orians throughout the course of this study. Dr. R. C. Snyder kindly read the manuscript. Many colleagues assisted with field work and were helpful in discussions of the data; in this regard I would especially like to thank T. H. Frazzetta, M. E. Kriebel, K. P. Mauzey, E. R. Pianka, C. C. Smith, L. W. Spring, and M. F. Willson. My wife, Marlene, processed many of the raw field data and was responsible for lettering most of the figures. Working facilities were provided by the Department of Zoology, University of Washington, and financial assistance was provided by National Science Foundation predoctoral fellowships (1960-1963). STUDY AREAS At Seattle, two marshes (Red, 6.3 acres, and Blue, 3.3 acres) in the University of Washington Arboretum were studied in 1961. -

Avian Response to Meadow Restoration in the Central Great Plains

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center US Geological Survey 2006 Avian Response to Meadow Restoration in the Central Great Plains Rosalind B. Renfrew Vermont Center for Ecostudies Douglas H. Johnson USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, [email protected] Gary R. Lingle Assessment Impact Monitoring Environmental Consulting W. Douglas Robinson Oregon State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Renfrew, Rosalind B.; Johnson, Douglas H.; Lingle, Gary R.; and Robinson, W. Douglas, "Avian Response to Meadow Restoration in the Central Great Plains" (2006). USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center. 236. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsnpwrc/236 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in PRAIRIE INVADERS: PROCEEDINGS OF THE 20TH NORTH AMERICAN PRAIRIE CONFERENCE, UNIVERSITY OF NEBRASKA AT KEARNEY, July 23–26, 2006, edited by Joseph T. Springer and Elaine C. Springer. Kearney, Nebraska : University of Nebraska at Kearney, 2006. Pages 313-324. AVIAN RESPONSE TO MEADOW RESTORATION IN THE CENTRAL GREAT PLAINS ROSALIND B. RENFREW, Vermont Center for Ecostudies, P.O. Box 420, Norwich, VT 05055, USA DOUGLAS H. JOHNSON, U.S. Geological Survey, Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center, Saint Paul, MN 55108, USA GARY R. LINGLE, Assessment Impact Monitoring Environmental Consulting, 1568 L Road, Minden, NE 68959, USA W. -

The Marsh Wren Braddock Bay Bird Observatory

Fall 2016 www.bbbo.org The Marsh Wren Braddock Bay Bird Observatory A non-profit organization dedicated to ornithological research, education, and conservation. Feather by Feather ave you ever wondered what our banders are molt begins in the nest, and for others it takes place weeks looking at when they peer so intently at a bird’s tail to months after fledging. While the flight feathers of the or wing, smoothing the feathers or fanning them wing and tail are typically not replaced during this molt, Hout for a better view? The simple answer is . molt! the body plumage is replaced with feathers much closer in appearance to adult feathers. All About Molt At the end of the breeding season, adult passerines in North America undergo a complete molt of all body and flight In addition to determining a bird’s appearance, feathers feathers, resulting in a uniform coat of feathers termed the serve many important functions including insulation from “basic plumage”. Some species have an additional molt - the elements and flight control. Feathers wear out over time, typically in the spring - to prepare for the breeding season. and so all birds replace their feathers in predictable patterns This molt, called the “prelternate molt”, is typically not on an annual cycle. The process of feather replacement is complete and may involve only a few feathers on the body called “molt.” and wing. Birds like ducks and geese are covered with fuzzy downy feathers when they hatch, but passerines hatch essentially Juvenal Feathers Tell the Tale featherless. They have, or may acquire, a sparse coat of natal down but these wispy feathers are quickly replaced Juvenal feathers are different than their adult counterparts. -

Comprehensive Report Species - Cistothorus Platensis Page I of 19

Comprehensive Report Species - Cistothorus platensis Page I of 19 NatureServe () EXPLORER • '•rr•K•;7",,v2' <-~~~ •••'F"'< •j • ':'•k• N :;}• <"• Seach bot. the Dat -Abou-U Cot Chana eCrite «<Previous I Next»> Cistothorusplatensis - (Latham, 1790) Google, Sedge Wren Search for Images on Google Spanish Common Names: Chivirin Sabanero, Chercan de las Vegas French Common Names: Troglodyte & bec court Other Common Names: Curruira-do-Campo Unique Identifier: ELEMENTGLOBAL.2.105322 Element Code: ABPBG10010 Informal Taxonomy: Animals, Vertebrates - Birds - Perching Birds Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Genus Animalia Craniata Aves Passeriformes Troglodytidae Cistothorus Genus Size: B - Very small genus (2-5 species) Check this box to expand all report sections: Concept Reference 0 Concept Reference: American Ornithologists' Union (AOU). 1998. Check-list of North American birds. Seventh edition. American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, DC. 829 pp. Concept Reference Code: B98AOU01NAUS Name Used in Concept Reference: Cistothorusplatensis Taxonomic Comments: Formerly known as Short-billed Marsh-Wren. Composed of three groups: STELLARIS (Sedge Wren), PLATENSIS (Western Grass-Wren), and POLYGLOTTUS (Eastern Grass-Wren) (AOU 1998). Constitutes a superspecies with C. MERIDAE and C. APOLINARI (AOU 1998). Conservation Status 0 NatureServe Status Global Status: G5 Global Status Last Reviewed: 03Dec1996 Global Status Last Changed: 03Dec1996 Rounded Global Status: G5 - Secure Nation: United States National Status: N4B,N5N Nation: Canada National Status:N5B -

Conspecific Nest Aggression of The

CONSPECIFIC NEST AGGRESSION OF THE PACIFIC WREN ON VANCOUVER ISLAND, BRITISH COLUMBIA ANN NIGHTINGALE and RON MELCER, JR., Rocky Point Bird Observatory, Suite #170, 1581-H Hillside Avenue, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada V8T 2C1; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Five of the ten wren species in North America are known to destroy nests of conspecifics. These include the Cactus Wren (Campylorhynchus brunneica- pillus), Bewick’s Wren (Thryomanes bewickii), Sedge Wren (Cistothorus platensis), Marsh Wren (Cistothorus palustris), and House Wren (Troglodytes aedon). However, none of the Winter Wren complex, recently split as the Winter Wren (Troglodytes hiemalis), Pacific Wren (T. pacificus), and Eurasian Wren (T. troglodytes), have been documented to do so in experiments or by observation of natural behavior. Here we present a detailed chronology of a nesting of the Pacific Wren—the first report of conspecific nest aggression in the Winter Wren complex. On 15 May 2011, in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a Pacific Wren approached another’s nest under video surveillance and removed two 9-day-old chicks. The nonparental adult returned to the nest, apparently attempting to kill and/or and remove the remaining two chicks, several times over 4.75 hours but was not successful. Although our findings are limited to a single event, they are consistent with those of other wrens. Birds are known to destroy the nests and eggs or remove the young from nests of other species, as well as conspecifics, to reduce competition for nests, food, perches, and, in polygynous species, for the male’s parental care (Fox 1975, Verner 1975, Picman 1977a, Jones 1982). -

Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba

ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE BIRDS OF CUBA Number 3 2020 Nils Navarro Pacheco www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com 1 Senior Editor: Nils Navarro Pacheco Editors: Soledad Pagliuca, Kathleen Hennessey and Sharyn Thompson Cover Design: Scott Schiller Cover: Bee Hummingbird/Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae), Zapata Swamp, Matanzas, Cuba. Photo courtesy Aslam I. Castellón Maure Back cover Illustrations: Nils Navarro, © Endemic Birds of Cuba. A Comprehensive Field Guide, 2015 Published by Ediciones Nuevos Mundos www.EdicionesNuevosMundos.com [email protected] Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba ©Nils Navarro Pacheco, 2020 ©Ediciones Nuevos Mundos, 2020 ISBN: 978-09909419-6-5 Recommended citation Navarro, N. 2020. Annotated Checklist of the Birds of Cuba. Ediciones Nuevos Mundos 3. 2 To the memory of Jim Wiley, a great friend, extraordinary person and scientist, a guiding light of Caribbean ornithology. He crossed many troubled waters in pursuit of expanding our knowledge of Cuban birds. 3 About the Author Nils Navarro Pacheco was born in Holguín, Cuba. by his own illustrations, creates a personalized He is a freelance naturalist, author and an field guide style that is both practical and useful, internationally acclaimed wildlife artist and with icons as substitutes for texts. It also includes scientific illustrator. A graduate of the Academy of other important features based on his personal Fine Arts with a major in painting, he served as experience and understanding of the needs of field curator of the herpetological collection of the guide users. Nils continues to contribute his Holguín Museum of Natural History, where he artwork and copyrights to BirdsCaribbean, other described several new species of lizards and frogs NGOs, and national and international institutions in for Cuba. -

Marsh Wren Cistothorus Palustris

Appendix A: Birds Marsh Wren Cistothorus palustris Federal Listing N/A State Listing N/A Global Rank G5 State Rank S3 Regional Status High Photo by Pamela Hunt Justification (Reason for Concern in NH) Secretive marsh birds like the Marsh Wren have generally been considered conservation priorities because of known losses of wetland habitats, combined with often poor data on species’ distribution, abundance, and trend. In the case of the Marsh Wren, repeated Breeding Bird Atlases in the Northeast have consistently documented stable or increasing range occupancy (Cadman et al. 2007, McGowan and Corwin 2008, Renfrew 2013, MassAudubon 2014). The Breeding Bird Survey does a better job of estimating trends for Marsh Wren than other wetland birds, and based on BBS data populations are generally increasing or stable, although most data are from the West and Midwest (Sauer et al. 2014). Data for the Northeast are more equivocal, with declines in some areas, increases in others, and few significant trends. There are no data on trends in New Hampshire, although there is some evidence for local extirpations related to changes in habitat. Distribution Breeds across southern Canada and the northern and western United States, and along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts. There is also an isolated population in central Mexico (Kroodsma and Verner 2014). Winters in the western and coastal portions of the breeding range, and also in much of Mexico and the southwestern U.S. In New Hampshire, most breeding season records are from two general areas: the Connecticut River valley and Great Bay/Seacoast, with scattered records elsewhere inland where suitable habitat is present.