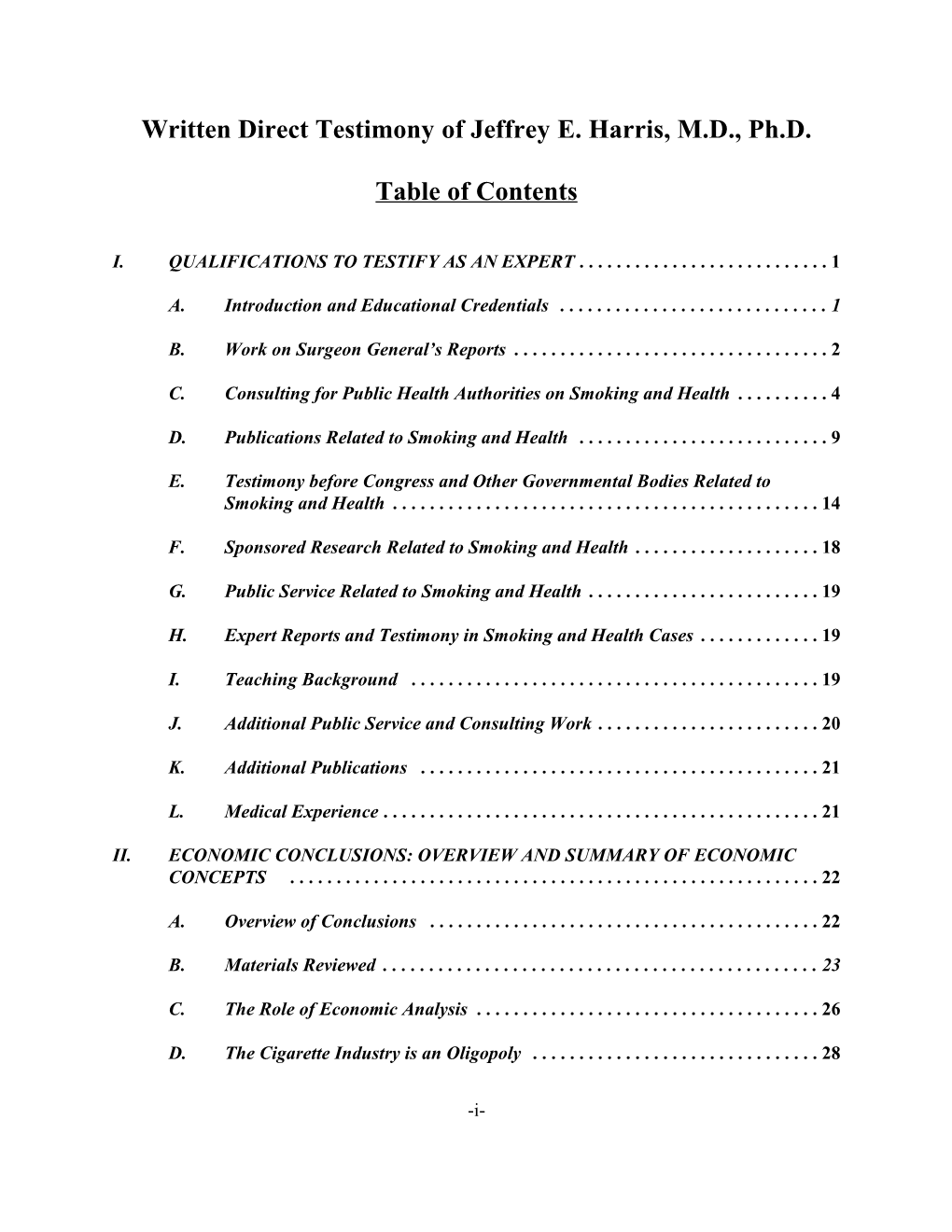

Written Direct Testimony of Jeffrey E. Harris, M.D., Ph.D. Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Findley Davies Virginia CEO Pay Report Estimated Compensation

Business Trends: Executive Compensation CEO ranking based on total The Findley Davies Virginia CEO Pay Report estimated compensation Compensation of CEOs at Virginia’s public companies with annual revenue of at least $1 billion COMPANY PERFORMANCE % Change % Change % Change Previous year % change Total 1 Year total Total Fiscal year Fiscal year Company name Executive name Base salary Previous year from Bonus Previous year from Total salary from Equity awards Long-term Other Total estimated total estimated from compensation shareholder return vs. revenues net income base salary previous bonus previous and bonus previous cash awards compensation compensation compensation previous (as disclosed return S&P500** ($ millions) ($ millions) year year year year in latest proxy) General Dynamics Corp., Falls Church Nicholas D. Chabraja $ 1,375,000 $ 1,300,000 5.8% $ 4,500,000 $ 3,500,000 29% $ 5,875,000 22.4% $ 25,619,046 N/A $ 404,603 $ 31,898,649 $ 15,634,585 104.0% $ 21,926,640 -33.78% 4.71% $ 29,300.0 $ 2,478.0 Norfolk Southern Corp., Norfolk Charles W. Moorman 950,000 800,000 18.8 1,759,400 862,400 104 2,709,400 63.0 9,639,106 N/A 132,239 12,480,745 12,637,254 -1.2 14,226,049 -4.30 34.19 10,661.0 1,716.0 Dominion Resources Inc., Richmond Thomas F. Farrell II 1,191,667 1,100,000 8.3 2,355,000 4,402,400 -47 3,546,667 -35.5 3,107,029 $ 4,380,000 626,421 11,660,117 12,930,286 -9.8 14,285,252 -21.14 19.16 16,290.0 1,836.0 Brinks Co.1, Richmond Michael T. -

A Review of Tobacco Harm Reduction Hearing Committee on Energy and Commerce House of Representatives

CAN TOBACCO CURE SMOKING? A REVIEW OF TOBACCO HARM REDUCTION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, TRADE, AND CONSUMER PROTECTION OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 3, 2003 Serial No. 108–31 Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/house VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:52 Sep 04, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 87489.TXT HCOM1 PsN: HCOM1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:52 Sep 04, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 87489.TXT HCOM1 PsN: HCOM1 CAN TOBACCO CURE SMOKING? A REVIEW OF TOBACCO HARM REDUCTION VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:52 Sep 04, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 87489.TXT HCOM1 PsN: HCOM1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:52 Sep 04, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 87489.TXT HCOM1 PsN: HCOM1 CAN TOBACCO CURE SMOKING? A REVIEW OF TOBACCO HARM REDUCTION HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, TRADE, AND CONSUMER PROTECTION OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED EIGHTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION JUNE 3, 2003 Serial No. 108–31 Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.access.gpo.gov/congress/house U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 87–489PDF WASHINGTON : 2003 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:52 Sep 04, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 87489.TXT HCOM1 PsN: HCOM1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 10:52 Sep 04, 2003 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 87489.TXT HCOM1 PsN: HCOM1 COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE W.J. -

Best Places to Launch a Career” Ranking That This Book Is Based Upon Requires Surveys of Career Services Directors, Students, and Employers Themselves

The Best Places toLaunch a Career This page intentionally left blank BusinessWeek Fast Track The Best Places toLaunch a Career Lindsey Gerdes New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto Copyright © 2008 by McGraw-Hill. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 0-07-160114-7 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-149655-6. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069. TERMS OF USE This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon, transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. -

Appendices to Final Mem & Order\Appendix a Part 1.Wpd

APPENDIX A Excerpts from United States v. Philip Morris USA. Inc., et al. — F. Supp. 2d —, No. 99-2496 (GK), 2006 WL 2380622, 2006 WL 2380648, 2006 WL 2380632, 2006 WL 2381449, 2006 WL 2380650, and 2006 WL 2380681 (D.D.C. Aug. 17, 2006). [The Table of Contents from the opinion itself follows. Italicized headings appear in whole or in part in this appendix. Note that the page numbers in this table of contents do not correspond to the pages in this appendix. Footnotes have been omitted or moved to the text in brackets.] TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................1 A. Overview ........................................................1 B. Preliminary Guidance for the Reader..................................5 II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY...............................................10 III. CREATION, NATURE, AND OPERATION OF THE ENTERPRISE.....................................................15 A. Pre-1953 Overview–The Rise in American Smoking and the Status of Scientific Research on Smoking and Health ..............16 B. Creation of the Enterprise ..........................................18 C. TIRC/CTR -- Tobacco Industry Research Committee/Council for Tobacco Research-USA .........................................26 1. Selection and Approval of TIRC’s Scientific Advisory Board Members and Scientific Director .........................37 2. Research Activities of TIRC/CTR ..............................43 3. Public Relations Activities of TIRC/CTR ........................50 4. Publications and Public Statements -

Tobacco Companies: Philip Morris Without Some of the Risks of Smoking

56 RESEARCH Says: Cigarette Market Share 57 Chapter These companies remain some of the most Sweden Finland by country, 2008 Norway . This is thanks in part to their endless British Estonia “profitable in the world American Russian United Kingdom Tobacco Latvia Fed. 18 London, inventive ways of undermining and circumventing regulation. Lithuania Denmark Russian Federation Ireland Philip Morris USA/ Anna Gilmore, University of Bath, UK, 2011 Netherlands Belarus Philip Morris International ” Canada Poland Imperial Tobacco Group Germany Bristol, UK Belgium n recent years, publicly traded tobacco Nicoventures, a separate company dedicated to Czech Rep. Ukraine British American Tobacco Philip Morris International Slovakia Rep. Lausanne, Switzerland Austria Moldova I companies have consolidated through creating alternative nicotine products that offer Switz. Hungary Slovenia— France —Croatia Romania Imperial Tobacco Group privatization and mergers. Today there are five the same experience expected from cigarettes Bosnia & Herzegovina Serbia Kazakhstan Japan Tobacco/ major private tobacco companies: Philip Morris without some of the risks of smoking. Bulgaria Albania —FYR Japan Japan Tobacco International Philip Morris International Italy Macedonia DPR Portugal Uzbekistan China National International, Altria/Philip Morris USA, Japan New York, NY Spain Georgia Kyrgyzstan Korea United States of America Greece Tobacco Corporation Korea Estimates of revenues from the global tobacco Armenia— —Azerbaijan Beijing State-Owned Tobacco Company Turkmenistan Rep Tobacco International, British American Altria Group/Philip Morris USA Turkey industry vary widely but are likely approaching Richmond, VA —Malta Syrian Tobacco, and Imperial Tobacco. In addition to Tunisia Cyprus— China Japan Tobacco/ Other Arab Rep. Japan Tobacco International half a trillion dollars annually. Although Lebanon*— Isl. -

One Disastrous Summer

nb36p01.qxp 8/31/2007 8:11 PM Page 1 TOP STORIES BUSINESS LIVES NYSE puts a big Book clubs, bet on its new tech New York-style guru’s software as PAGE 43 it seeks to expand PAGE 2 ® WNBC seeks to shake up local TV scene with VOL. XXIII, NO. 36 WWW.NEWYORKBUSINESS.COM SEPTEMBER 3-9, 2007 PRICE: $3.00 7 p.m. newscast PAGE 2 The Plaza Bikini babes hand out freebies for delays Riese Restaurants NEW YORK, NEW YORK, P. 6 reopening Looking for fallout from credit crisis? until ’08 Just wait until next year Construction woes; GREG DAVID, PAGE 13 questions loom Slow growth pays on rehiring workers off for real estate MEN AT WORK: Jerry BY LISA FICKENSCHER information firm Gottlieb just got back SMALL BUSINESS, P 34 into his office, which is still a construction the much-anticipated reopen- zone, near the steam ing of The Plaza hotel has been pipe blast site. pushed back until next year, dash- ing a plan to celebrate the hotel’s david neff david 100th anniversary in grand style. “Oct.1 is such a significant date BUSINESS INTERRUPTION for us,” says the hotel’s general manager, Shane Krige. “It would have been fantastic to open then.” The hotel is now accepting reservations for Jan. 1. REPORT One disastrous summer As The Plaza gears up for its re- REAL ESTATE opening, tensions are simmering of them have yet to recover from a to return—to gutted offices.Walls, between the hotel union and new G Condo developers Around the city, series of random disasters, from the flooring, furniture and equipment management over who will work struggle to finance affected businesses steam pipe explosion in July to the had been removed by cleanup there. -

Altria Group Inc

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549-4561 (iDIVISION OF CORPORATION FINANCE April 2, 2010 Louana O. Heuhsen Vice President and Associate General Counsel AltraGroup, Inc. 6601 West Broad Street Richmond, VA 23230 Re: Altra Group, Inc. Incoming letter dated March 30, 2010 Dear Ms. Heuhsen: This is in response to your letter dated March 30,2010 concernng the shareholder proposal submitted tô Altra by Chrs Rossi. We also have received letters on the proponent's behalf dated March 30,2010, March 31,2010, and April 1, 2010. Our response is attached to the enclosed photocopy of your correspondence. By doing this, we avoid having to recite or summarze the facts set forth in the correspondence. Copies of all of the correspondence also wil be provided to the proponent. In connection with this matter, your attention is directed to the enclosure, which sets fort a brief díscussion of the Division's informal procedures regarding shareholder proposals. Sincerely, Heather L. Maples Senior Special Counsel Enclosures cc: John Chevedden *** FISMA & OMB Memorandum M-07-16 *** April 2, 2010 Response of the Offce of Chief Counsel Division of Corporation Finance Re: Altra Group, Inc. Incoming letter dated March 30, 2010 The proposal relates to acting by written consent. There appears to be some basis for your view that Altra may exclude the proposal under rule 14a-8(e)(2) because Altra received it after the deadline for submitting proposals. We note in paricular your representation that Altra had not received the proposal as of March 30, 2010 and that the e-mail address apparently used for delivery is the inactive e-mail address of the company's former corporate secretary. -

Altria Group Inc

ALTRIA GROUP INC FORM 10-K (Annual Report) Filed 3/15/2005 For Period Ending 12/31/2004 Address 120 PARK AVE NEW YORK, New York 10017 Telephone 917-663-4000 CIK 0000764180 Industry Tobacco Sector Consumer/Non-Cyclical Fiscal Year 12/31 Table of Contents UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2004 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from to Commission File Number 1-8940 ALTRIA GROUP, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Virginia 13-3260245 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 120 Park Avenue, 10017 New York, N.Y. (Zip Code) (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: 917-663-4000 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of Each Class Name of Each Exchange on Which Registered Common Stock, $0.33 1 / 3 par value New York Stock Exchange Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Printmgr File

2015 PROXY STATEMENT 2015 Proxy Statement Contents 1 Notice of Annual Meeting 2 Proxy Statement Summary 6 Questions and Answers About the Annual Meeting and Voting 10 Corporate Governance and Board Matters Director Independence Related Party Transactions Board Leadership Structure and Role in Risk Oversight Executive Sessions of Directors Committees and Meeting Attendance Compensation Committee Interlocks and Insider Participation Section 16(a) Beneficial Ownership Reporting Compliance Shareholder Proposals and Director Nominations Communications With Directors Non-Employee Director Compensation 19 Share Ownership 21 Item 1 — Election of Directors 26 The Audit Committee Report 27 Auditors 28 Item 2 — Ratification of Appointment of Auditors 29 Compensation, Governance and Nominating Committee Report 29 Compensation Discussion and Analysis Executive Summary Objectives of Dominion’s Executive Compensation Program and the Compensation Decision-Making Process Elements of Dominion’s Compensation Program Other Relevant Compensation Practices 50 Executive Compensation Summary Compensation Table Grants of Plan-Based Awards Outstanding Equity Awards at Fiscal Year-End Option Exercises and Stock Vested Pension Benefits Nonqualified Deferred Compensation Potential Payments Upon Termination or Change in Control Equity Compensation Plans 64 Item 3 — Advisory Vote on Approval of Executive Compensation (Say on Pay) 65 Item 4 — Approval of Amendment to Bylaws 66 Shareholder Proposals (Items 5-11) 80 Appendices Important Notice Regarding the Availability of Proxy Materials for Dominion’s 2015 Annual Meeting of Shareholders to be Held on May 6, 2015 Dominion’s Notice of Annual Meeting, 2015 Proxy Statement, 2014 Summary Annual Report and 2014 Annual Report on Form 10-K are available on our website at www.dom.com/proxy Notice of Annual Meeting Dominion Resources, Inc. -

Source: "Should Be Confined to VAT" (To a 1 5% VAT)

Report from the „Seminar on the taxation of tobacco in the European Union", 28-29 September 2006 (Budapest, Grand Hotel Royal): by Tibor Szilagyi [currently working at WHO Secretariat] The conference has been organised by the International Tax and Investment Center (ITIC), an international N'GO registered in the US. The website of this organisation (www. iticnei.org) previously acknowledged receiving support from tobacco companies. Audience: Around 50 people, representing primarily finance ministries and financial research institutes from Central and Eastern Ruropean countries. The only speaker from the Ruropean Commission has been Mr Alexander Wiedovv, director of indirect taxation and tax administration of the EC. The Chairman of the conference has been Prof Sijbren Cnossen of the University of Maastricht. Another key speaker Mr Adrian Cooper (UK), managing director of Oxford Economic Forecasting. Both have been actively put forward tobacco industry arguments with regard to taxation of tobacco products. The latter has published a ..special report" with this occasion, entitled ..Addressing the RU cigarette excise regime review 2006". The report ~ the introduction says ••- analyses the strengths and weaknesses of the RU taxation regime and ..considers how it should be reformed". The report considers the escalation of the black market as a sign of a ..destabilized cigarette market", which is primarily caused by tax and price increases. The report publishes a table (page 10) on the share of black market in selected RU countries, mentioning as source ..industry estimates". It considers, for example, 25% of the Hungarian or 35% of Lithuanian market as ..black", without even mentioning on which basis these estimates have been made. -

United States District Court for the District of Columbia

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ____________________________________ ) UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action ) No. 99-CV-02496 (GK) PHILIP MORRIS USA INC., ) f/k/a PHILIP MORRIS INC., et al., ) Next Scheduled Court Appearance: ) Trial (ongoing) Defendants. ) ____________________________________) WRITTEN DIRECT EXAMINATION OF MAX H. BAZERMAN, Ph.D. SUBMITTED BY THE UNITED STATES PURSUANT TO ORDERS #471 AND #924 1 I. SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS 2 Q: Please state your full name. 3 A: Max Hal Bazerman. 4 Q: What is your occupation Dr. Bazerman? 5 A: I am a professor at Harvard University. I also consult with a number of for-profit 6 corporations and non-profit organizations. 7 Q: You have been shown a copy of U.S. Ex. 89,457. Do you recognize this to be a 8 copy of your curriculum vitae as of December, 2004? 9 A: Yes. 10 Q: What were you asked to do by the United States as an expert in this case? 11 A: The United States has asked me (a) to outline theory from the field of behavioral decision 12 research relevant to potential remedies in this case, (b) to discuss applications of this theory to 13 business contexts, and (c) to apply that theory to this case. 14 Q: Based on this assignment, could you briefly describe the subject of your testimony? 15 A: The United States has instructed me to assume that it has established defendants' liability 16 and that defendants' misconduct continues to this day. Making those assumptions, and applying 17 theory from behavioral decision research as it relates to issues of incentive and bias, I conclude 18 that defendants' misconduct will continue absent significant Court intervention to change the 19 incentives and systematic biases operating on defendants' managers and executives. -

US Food and Drug Administration Jurisdiction Over Tobacco Products

Policy Forum Compromise or Capitulation? US Food and Drug Administration Jurisdiction Over Tobacco Products Stanton A. Glantz1*, Richard Barnes1, Sharon Y. Eubanks2 1 Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, California, United States of America, 2 Attorney in private practice, McLean, Virginia, United States of America On June 12, 2009, the United States Congress passed the Family Smoking Summary Points Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (S. 982), granting the US Food and Drug N On June 12, 2009, the US Congress passed compromise legislation granting the Administration (FDA) authority regulating Food and Drug Administration (FDA) jurisdiction over tobacco products, tobacco products. The idea of FDA repealing federal pre-emption of state and local regulation of tobacco advertising, and requiring graphical warning labels on tobacco products. regulation of tobacco has broad [1], but not unanimous, support among medical N Past legislative compromises with the tobacco industry have led to short-term and public health professionals. This law public health gains at the expense of long-term progress. has many strengths (Table 1): it grants the N The law offers the tobacco industry an opportunity to rehabilitate its image and FDA general authority over tobacco products because they are now ‘‘FDA regulated.’’ products, including the ability to reduce N Tobacco interests that have violated US racketeering law are inappropriately (but not eliminate) nicotine, requires represented on the Scientific Advisory Committee that influences FDA improved warning labels on cigarette and regulations. other tobacco packages, and implements N The challenge for the compromise law’s advocates will be to accept the rules limiting marketing of tobacco responsibility for these problems and see that their negative consequences products to youth that the FDA issued in do not materialize.