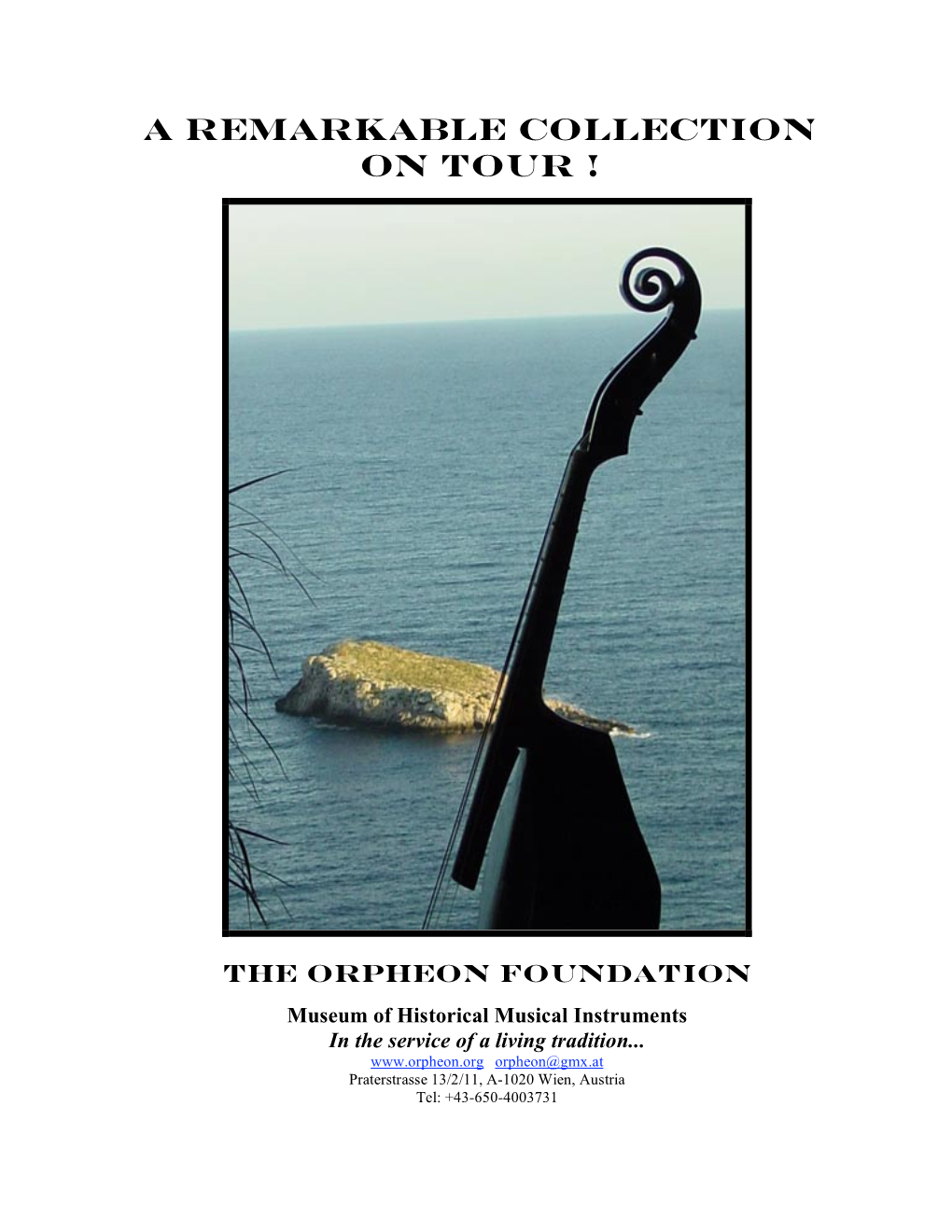

A Remarkable Collection on Tour !

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stowell Make-Up

The Cambridge Companion to the CELLO Robin Stowell Professor of Music, Cardiff University The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge CB2 1RP,United Kingdom The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK http://www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA http://www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia © Cambridge University Press 1999 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 1999 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Adobe Minion 10.75/14 pt, in QuarkXpress™ [] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0 521 621011 hardback ISBN 0 521 629284 paperback Contents List of illustrations [page viii] Notes on the contributors [x] Preface [xiii] Acknowledgements [xv] List of abbreviations, fingering and notation [xvi] 21 The cello: origins and evolution John Dilworth [1] 22 The bow: its history and development John Dilworth [28] 23 Cello acoustics Bernard Richardson [37] 24 Masters of the Baroque and Classical eras Margaret Campbell [52] 25 Nineteenth-century virtuosi Margaret Campbell [61] 26 Masters of the twentieth century Margaret Campbell [73] 27 The concerto Robin Stowell and David Wyn Jones [92] 28 The sonata Robin Stowell [116] 29 Other solo repertory Robin Stowell [137] 10 Ensemble music: in the chamber and the orchestra Peter Allsop [160] 11 Technique, style and performing practice to c. -

The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck

Performance Practice Review Volume 9 Article 7 Number 1 Spring The aB roque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Vanscheeuwijck, Marc (1996) "The aB roque Cello and Its Performance," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 9: No. 1, Article 7. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199609.01.07 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Instruments The Baroque Cello and Its Performance Marc Vanscheeuwijck The instrument we now call a cello (or violoncello) apparently deve- loped during the first decades of the 16th century from a combina- tion of various string instruments of popular European origin (espe- cially the rebecs) and the vielle. Although nothing precludes our hypothesizing that the bass of the violins appeared at the same time as the other members of that family, the earliest evidence of its existence is to be found in the treatises of Agricola,1 Gerle,2 Lanfranco,3 and Jambe de Fer.4 Also significant is a fresco (1540- 42) attributed to Giulio Cesare Luini in Varallo Sesia in northern Italy, in which an early cello is represented (see Fig. 1). 1 Martin Agricola, Musica instrumentalis deudsch (Wittenberg, 1529; enlarged 5th ed., 1545), f. XLVIr., f. XLVIIIr., and f. -

The Science of String Instruments

The Science of String Instruments Thomas D. Rossing Editor The Science of String Instruments Editor Thomas D. Rossing Stanford University Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA) Stanford, CA 94302-8180, USA [email protected] ISBN 978-1-4419-7109-8 e-ISBN 978-1-4419-7110-4 DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-7110-4 Springer New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2010 All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed is forbidden. The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks, and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer ScienceþBusiness Media (www.springer.com) Contents 1 Introduction............................................................... 1 Thomas D. Rossing 2 Plucked Strings ........................................................... 11 Thomas D. Rossing 3 Guitars and Lutes ........................................................ 19 Thomas D. Rossing and Graham Caldersmith 4 Portuguese Guitar ........................................................ 47 Octavio Inacio 5 Banjo ...................................................................... 59 James Rae 6 Mandolin Family Instruments........................................... 77 David J. Cohen and Thomas D. Rossing 7 Psalteries and Zithers .................................................... 99 Andres Peekna and Thomas D. -

Issue 189.Pmd

email: [email protected] NIGHTSHIFTwebsite: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every Oxford’s Music Magazine month. Issue 189 April 2011 YYYYYYoungoungoungoung KnivesKnivesKnivesKnives Go Pop! Out on their own and back with a brilliant new album photo: Cat Stevens NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] Online: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net WILCO JOHNSON AND listings for the weekend, plus ticket DEACON BLUE are the latest details, are online at names added to this year’s www.oxfordjazzfestival.co.uk Cornbury Festival bill. The pair join already-announced headliners WITNEY MUSIC FESTIVAL returns James Blunt, The Faces and for its fifth annual run this month. Status Quo on a big-name bill that The festival runs from 24th April also includes Ray Davies, Cyndi through to 2nd May, featuring a Lauper, Bellowhead, Olly Murs, selection of mostly local acts across a GRUFF RHYS AND BELLOWHEAD have been announced as headliners The Like and Sophie Ellis-Bextor. dozen venues in the town. Amongst a at this year’s TRUCK FESTIVAL. Other new names on the bill are host of acts confirmed are Johnson For the first time Truck will run over three full days, over the weekend of prog-folksters Stackridge, Ben Smith and the Cadillac Blues Jam, 22nd-24th July at Hill Farm in Steventon. The festival will also enjoy an Montague & Pete Lawrie, Toy Phousa, Alice Messenger, Black Hats, increased capacity and the entire site has been redesigned to accommodate Hearts, Saint Jude and Jack Deer Chicago, Prohibition Smokers new stages. -

The Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society Text Has Been Scanned With

The Journal of the Viola da Gamba Society Text has been scanned with OCR and is therefore searchable. The format on screen does not conform with the printed Chelys. The original page numbers have been inserted within square brackets: e.g. [23]. Where necessary footnotes here run in sequence through the whole article rather than page by page and replace endnotes. The pages labelled ‘The Viola da Gamba Society Provisional Index of Viol Music’ in some early volumes are omitted here since they are up- dated as necessary as The Viola da Gamba Society Thematic Index of Music for Viols, ed. Gordon Dodd and Andrew Ashbee, 1982-, available on-line at www.vdgs.org.uk or on CD-ROM. Each item has been bookmarked: go to the ‘bookmark’ tab on the left. To avoid problems with copyright, some photographs have been omitted. Volume 31 (2003) Editorial, p. 2 Pamela Willetts Who was Richard Gibbon(s)? Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 3-17 Michael Fleming How long is a piece of string? Understanding seventeenth- century descriptions of viols. Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 18-35 David J. Rhodes The viola da gamba, its repertory and practitioners in the late eighteenth century. Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 36-63 Review Annette Otterstedt: The Viol: History of an Instrument, Thomas Munck Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 64-67 Letter (and reprinted article) Christopher Field: Hidden treasure in Gloucester Chelys, vol. 31 (2003), pp. 68-71 EDITORIAL It is strange, but unfortunately true, that to many people the term 'musicology' suggests an arid intellectual discipline far removed from the emotional immedi- acy of music. -

A Performer's Guide to Hertl's Concerto for Double Bass

A Performer's Guide To Frantisek Hertl's Concerto for Double Bass Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Roederer, Jason Kyle Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 15:16:02 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194487 A PERFORMER’S GUIDE TO HERTL’S CONCERTO FOR DOUBLE BASS by Jason Kyle Roederer ________________________ Copyright © Jason Kyle Roederer 2009 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2009 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Jason Kyle Roederer entitled A Performer’s Guide to Hertl’s Concerto for Double Bass and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Patrick Neher _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Mark Rush _______________________________________________________Date: April 17, 2009 Thomas Patterson Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Jan. 6, 1970 M

Jan. 6, 1970 M. TANSKY 3,487,740 VIOLIN WITH TIMBRE BASS BAR Filed May 9, 1968 c?????? NivENTOR NA CA E TANSKY’ AORNEYS 3,487,740 United States Patent Office Patented Jan. 6, 1. 970 2 Still further objects and advantages of the present in 3,487,740 VIOLIN WITH TEMBRE BASSBAR Vention will readily become apparent to those skilled in the Michael Tansky, 541 Olive Ave., art to which the invention pertains on reference to the Long Beach, Calif. 90812 following detailed description. Filed May 9, 1968, Ser. No. 727,774 5 Description of the drawing ? . , Int. CI. G10d 1/02 0 The description refers to the accompanying drawing in U.S. C. 84-276 6 Claims which like reference characters refer to like parts through out the several views in which: FIGURE 1 is a longitudinal sectional view of the sound ABSTRACT OF THE DISCLOSURE O box of a violin showing the bass bar embodying my in A violin having an elongated, internally mounted bass vention; , ; bar with a continuous series of conical cavities extending FIGURE 2 is a view of the preferred bass bar, sepa along its inner longitudinal edge and facing the back of rated from the instrument as along one of its longitudinal the instrument. The bass bar results in the violin pro edges; w ` ? - . ducing pure, limpid tones while the cavities reduce the FIGURE3 is a view of the opposite longitudinal edge weight of the bass bar. Y. of the preferred bass bar; and : ... TSSSLSLSSSSLLLLL SLLS0L0LSLSTM SM FIGURE 4 is a fragmentary perspective view of the Background of the invention mid-section of the preferred bass bar. -

Jazz, Identity and Sound Design in a Melting Pot

ACADEMY OF MUSIC AND DRAMA Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Lauri Kallio Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 HEC, Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Spring, 2019 Independent Project (Degree Project), 15 higher education credits Bachelor of Fine Arts in (Name of Program) Academy of Music and Drama, University of Gothenburg Spring, 2019 Author: Lauri Kallio Title: Jazz, identity and sound design in a melting pot Supervisor: Dr. Joel Eriksson Examiner: ABSTRACT In this piece of artistic research the author explores his musical toolbox and aesthetics for creating music. Finding compositional and music productional identity are also the main themes of this work. These aspects are being researched through the process creating new music. The author is also trying to build a bridge between his academic and informal studies over the years. The questions researched are about originality in composition and sound, and the challenges that occur during the working period. Key words: Jazz, Improvisation, Composition, Music Production, Ensemble, Free, Ambient 2 (34) Table of contents: 1. Introduction 1.1. Background 4 1.2. Goal and Questions 5 1.3. Method 6 2. Pre-recorded material 2.1.” 2147” 6 2.2. ”SAKIN” 7 2.3. ”BLE” 8 2.4. The selected elements 9 3. The compositions 3.1. “Mobile” 10 3.1.2. The rehearsing process 11 3.2. “ONEHE-274” 12 3.2.2. The rehearsing process 14 3.3. “TURBULENCE” 15 3.3.2. The rehearsing process 16 3.4. Rehearsing with electronics only 17 4. Conclusion 19 5. Afterword 20 6. -

Baryton Trios, Vol. 2

Franz Josef Haydn Baryton trios Arranged for two clarinets and bassoon by Ray Jackendoff SCORE Volume 2 Trio 101 in Bb Trio 77 in F Trio 106 in C Franz Josef Haydn ! Baryton trios The baryton was a variation on the viola da gamba, with seven bowed strings and ten sympathetic strings. Haydn’s employer, Prince Nikolaus von Esterházy, played this instrument, and so it fell to Haydn to compose for it. Between 1761 and 1775 he wrote 126 trios for the unusual combination of baryton, viola, and cello, as well as other solo and ensemble works for baryton. As might be expected, many are rather routine. But some are quite striking, and reflect developments going on in Haydn’s composition for more customary ensembles such as the symphony and the string quartet. The six trios selected here are a sampling of the more !interesting among the trios. The trios are typically in three movements. The first movement is often slow or moderate in tempo; the other two movements are usually a fast movement and a minuet in one order or the other. Trio 96 is one of the few in a minor key; Trio 101 is unusual in having a fugal finale, !along the lines of the contemporaneous Op. 20 string quartets. In arranging these trios for two clarinets and bassoon, I have transposed all but Trio 96 down a whole step from the original key. I have added dynamics and articulations that have worked well in performance. We have found that the minuets, especially those that serve as final movements, !work better if repeats are taken in the da capo. -

Die Sammlung Historischer Streichinstrumente Der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank

OESTERREICHISCHE NATIONALBANK EUROSYSTEM Die Sammlung historischer Streichinstrumente der Oesterreichischen Nationalbank The collection of Historical String Instruments of the Oesterreichische Nationalbank Inhaltsverzeichnis Contents Impressum Medieninhaberin: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Otto-Wagner-Platz 3, 1090 Wien, T: (+43 1) 404 20-6605, F: (+43 1) 404 20-6697, www.oenb.at Redaktion: Mag. Brigitte Alizadeh-Gruber, Muna Kadum, Martina Leitner, Mag. Irene Mühldorf Grafik, Layout und Satz: Melanie Schuhmacher Fotos: © Graphisches Atelier Neumann, Wien Druck: Oesterreichische Nationalbank, Abteilung für Öffentlichkeitsarbeit und Publikationen, Gruppe Multimedia-, Internet- und Print-Service. © Oesterreichische Nationalbank, 2013. Streichinstrumente/ String Instruments 9 Amati Andrea 10 Violoncello, Cremona, spätes 16. Jh. 10 Bergonzi Carlo 12 Violine, Cremona 1723 12 Violine, Cremona nach 1724 14 Bergonzi Michelangelo 16 Violine, Cremona um 1740 16 Violine, „ex Hamma-Segelman“, Cremona um 1750 18 Camilli Camillus 20 Violine, Mantua 1736 20 Ceruti Giovanni Battista 22 Viola, Cremona um 1810 22 Gagliano Alessandro 24 Violoncello, Neapel ca. 1710 24 Grancino Giovanni 26 Violoncello, „ex Piatti“ – „ex Dunlop“, Mailand 1706 26 Guadagnini Giovanni Battista 28 Violoncello, „ex von Zweygberg“, Piacenza 174. 28 Violine, Mailand 1749 30 Violine, „ex Meinel“, Turin um 1770–1775 32 Violine, Turin 1772 34 Violine, „Mantegazza“, Turin 1774 36 Violine, Turin 177. 38 Viola, Turin 1784 40 Guarneri Andrea 42 Violine, Cremona, Mitte 17. Jh. 42 Guarneri del Gesù Giuseppe 44 Violine, „ex Sorkin“, Cremona 1731 44 Violine, „ex Guilet“, Cremona nach 1732 46 Violine, „ex Carrodus“, Cremona 1741 48 Lorenzini Gaspare 50 Violine, Piacenza um 1760 50 Maggini Giovanni Paolo 52 Viola, Brescia, frühes 17. Jh. 52 Montagnana Domenico 54 Violine, Venedig 1727 54 Seraphin Sanctus 56 Violine, Venedig 1733 56 Violine, „ex Hamma“, Venedig nach 1748 58 Silvestre Pierre 60 Violine, „ex Moser“, Lyon ca. -

A Micro-Tomographic Insight Into the Coating Systems of Historical Bowed String Instruments

coatings Article A Micro-Tomographic Insight into the Coating Systems of Historical Bowed String Instruments Giacomo Fiocco 1,2 , Tommaso Rovetta 1 , Claudia Invernizzi 1,3 , Michela Albano 1 , Marco Malagodi 1,4, Maurizio Licchelli 1 , Alessandro Re 5 , Alessandro Lo Giudice 5, Gabriele N. Lanzafame 6 , Franco Zanini 6, Magdalena Iwanicka 7, Piotr Targowski 8 and Monica Gulmini 2,* 1 Laboratorio Arvedi di Diagnostica Non-Invasiva, CISRiC, Università degli Studi di Pavia, Via Bell’Aspa 3, 26100 Cremona, Italy; giacomo.fi[email protected] (G.F.); [email protected] (T.R.); [email protected] (C.I.); [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (M.L.) 2 Dipartimento di Chimica, Università di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 5, 10125 Torino, Italy 3 Dipartimento di Scienze Matematiche, Fisiche e Informatiche, Università degli Studi di Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze 7/A, 43124 Parma, Italy 4 Dipartimento di Musicologia e Beni Culturali, Università degli Studi di Pavia, Corso Garibaldi 178, 26100 Cremona, Italy 5 Dipartimento di Fisica, Università di Torino and INFN, Sezione di Torino, Via Pietro Giuria 1, 10125 Torino, Italy; [email protected] (A.R.); [email protected] (A.L.G.) 6 Elettra-Sincrotrone Trieste S.C.p.A., S.S. 14 km 163.5, Basovizza, 34194 Trieste, Italy; [email protected] (G.N.L.); [email protected] (F.Z.) 7 Institute of Art Conservation Science, Department of Fine Arts, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Sienkiewicza 30/32, 87-100 Toru´n,Poland; [email protected] 8 Institute of Physics, Department of Physics, Astronomy and Informatics, Nicolaus Copernicus University, Grudzi ˛adzka5, 87-100 Toru´n,Poland; ptarg@fizyka.umk.pl * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-011-670-5265 Received: 21 December 2018; Accepted: 28 January 2019; Published: 29 January 2019 Abstract: Musical instruments are tools for playing music, but for some of them—made by the most important historical violin makers—the myths hide the physical artwork. -

The String Family

The String Family When you look at a string instrument, the first thing you'll probably notice is that it's made of wood, so why is it called a string instrument? The bodies of the string instruments, which are hollow inside to allow sound to vibrate within them, are made of different kinds of wood, but the part of the instrument that makes the sound is the strings, which are made of nylon, steel or sometimes gut. The strings are played most often by drawing a bow across them. The handle of the bow is made of wood and the strings of the bow are actually horsehair from horses' tails! Sometimes the musicians will use their fingers to pluck the strings, and occasionally they will turn the bow upside down and play the strings with the wooden handle. The strings are the largest family of instruments in the orchestra and they come in four sizes: the violin, which is the smallest, viola, cello, and the biggest, the double bass, sometimes called the contrabass. (Bass is pronounced "base," as in "baseball.") The smaller instruments, the violin and viola, make higher-pitched sounds, while the larger cello and double bass produce low rich sounds. They are all similarly shaped, with curvy wooden bodies and wooden necks. The strings stretch over the body and neck and attach to small decorative heads, where they are tuned with small tuning pegs. The violin is the smallest instrument of the string family, and makes the highest sounds. There are more violins in the orchestra than any other instrument they are divided into two groups: first and second.