On Ninazu, As Seen in the Economic Texts of the Early Dynastic Lagas (1)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Readingsample

Schlangendarstellungen in Mesopotamien und Iran vom 8. bis 2. Jt. v. Chr. Quellen, Deutungen und kulturübergreifender Vergleich Bearbeitet von Birgit Kahler Erstauflage 2015. Taschenbuch. 140 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 95935 056 3 Format (B x L): 15,5 x 22 cm Weitere Fachgebiete > Geschichte > Alte Geschichte & Archäologie > Altorientalische Geschichte & Archäologie schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Leseprobe Textprobe 3.1.4 Ningizzid Ningizzida ist wie sein Vater Ninazu ein Unterwelts- und Kriegsgott. Man kann davon ausgehen, dass er in Lagaš von Gudea eingeführt wurde, da er dort erst mit diesem auftaucht, wohingegen er in Ešnunna früher schon sehr oft zu sehen ist. Gudea beruft sich auf ihn in Verbindung mit Fruchtbarkeit („a god of much good progeny”). Sein zweiter Name Gišbanda, junger Baum, ist sowohl in der Nippur-Götterliste enthalten, als auch der Name seines Kultzentrums zwischen Ur und Lagaš. Dieses Zentrum erscheint nicht in Wirtschaftstexten, sondern wird nur in Tempelhymnen als „ehrfurchteinflößender Platz mitten auf dem Feld” genannt Schlange und Wurzeln Interessant ist in diesem Zusammenhang, dass man Schlangen und Baumwurzeln für identisch ansah und demzufolge das Wort Wurzel mit dem Bild überkreuzter Schlangen schrieb. Hierzu passt auch die Geschichte von Inanna, wie sie in ihrem Garten in Uruk einen Baum pflanzt, in dessen Wurzelwerk eine Schlange nistet Inanna fischt einen ausgerissenen Baum aus dem Fluss und pflanzt ihn in ihrem Garten in Uruk ein, um daraus später ein Bett und einen Stuhl zu fertigen. -

NINAZU, the PERSONAL DEITY of GUDEA Toshiko KOBAYASHI*

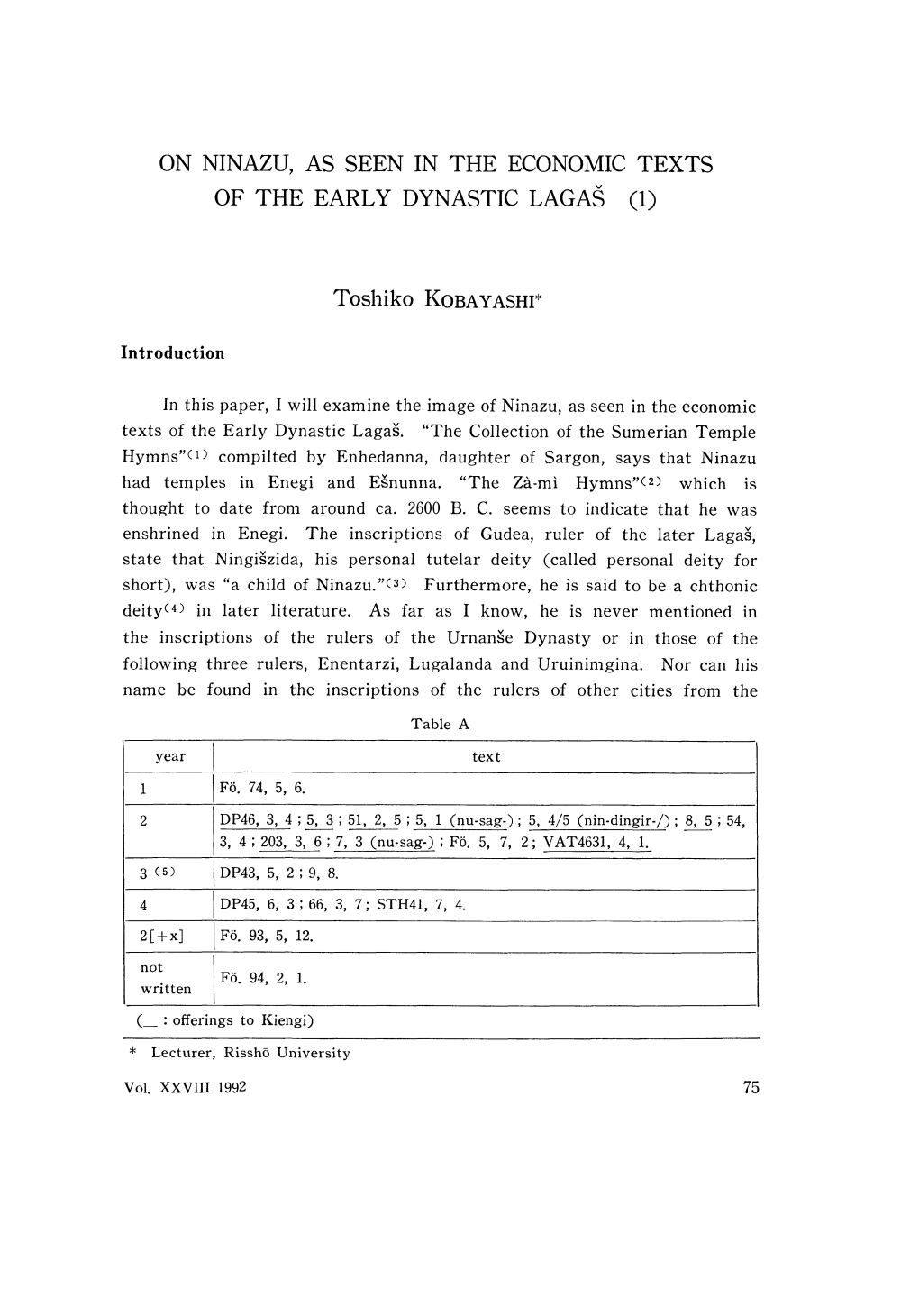

NINAZU, THE PERSONAL DEITY OF GUDEA -The Continuity of Personal Deity of Rulers on the Royal Inscriptions of Lagash- Toshiko KOBAYASHI* I. Introduction 1. Historical materials from later periods For many years, I have examined the personal deities of rulers in Pre- Sargonic Lagash.(1) There are not many historical materials about the personal deities from Pre-Sargonic times. In as much as the materials are limited chiefly to the personal deities recorded in the royal inscriptions, not all aspects of personal deities are clear. In my paper "On Ninazu, as Seen in the Economic Texts of the Early Dynastic Lagas (1)" in Orient XXVIII, I discussed Ninazu, who appears in the administrative-economic texts of Pre-Sargonic Lagash. Ninazu appears only in the offering-lists in the reign of Uruinimgina, the last ruler of Pre-Sargonic Lagash. Based only on an analysis of the offering-lists, I argued that Ninazu was the personal deity of a close relative of Uruinimgina. In my investigation thus far of the extant historical materials from Pre-Sargonic Lagash, I have not found any royal inscriptions and administrative-economic texts that refer to Ninazu as dingir-ra-ni ("his deity"), that is, as his personal deity. However, in later historical materials two texts refer to Ninazu as "his deity."(2) One of the texts is FLP 2641,(3) a royal inscription by Gudea, engraved on a clay cone. The text states, "For his deity Ninazu, Gudea, ensi of Lagash, built his temple in Girsu." Gudea is one of the rulers belonging to prosperous Lagash in the Pre-Ur III period; that is, when the Akkad dynasty was in decline, after having been raided by Gutium. -

Inanna a Commentary on Scenes of the Play

Inanna A Commentary on Scenes of the Play What is an Archetype? ‘Archetype’ defies simple definition. The word comes from the Greek arche and tupos. Arche means ‘first principle’ i.e. the creative source which cannot be seen directly. Tupos means ‘impression’ i.e. one of many manifestations of the first principle. Carl Jung said: … their origin can only be explained by assuming them to be deposits [in the unconscious] of the constantly repeated experiences of humanity. (CW7:109) It is an inherited tendency of the human mind to form representations of mythological motifs … that vary a great deal without losing their basic pattern … this tendency is instinctive, like the specific impulse of nest-building, migration, etc. in birds. (CW18:52) The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences. (CW 8: 230) The contents of the collective unconscious are not only residues of archaic specifically human modes of functioning, but also the residues of functions from [our] animal ancestry … (CW7:159) Inanna and the pantheon of gods and goddesses are universally imagined concepts that emerge from the silt of the Unconscious. They serve as beacons that point the way in a life that is vast and lonely. From the beginning of time, humans have dreamt with desire and fear about their forebears: their mothers, fathers and children; their wise elders, their kings and queens, heroes, princes and princesses; martyrs, saints, demons and fools. The procession of emotionally laden images is endless. -

Mesopotamian Culture

MESOPOTAMIAN CULTURE WORK DONE BY MANUEL D. N. 1ºA MESOPOTAMIAN GODS The Sumerians practiced a polytheistic religion , with anthropomorphic monotheistic and some gods representing forces or presences in the world , as he would later Greek civilization. In their beliefs state that the gods originally created humans so that they serve them servants , but when they were released too , because they thought they could become dominated by their large number . Many stories in Sumerian religion appear homologous to stories in other religions of the Middle East. For example , the biblical account of the creation of man , the culture of The Elamites , and the narrative of the flood and Noah's ark closely resembles the Assyrian stories. The Sumerian gods have distinctly similar representations in Akkadian , Canaanite religions and other cultures . Some of the stories and deities have their Greek parallels , such as the descent of Inanna to the underworld ( Irkalla ) resembles the story of Persephone. COSMOGONY Cosmogony Cosmology sumeria. The universe first appeared when Nammu , formless abyss was opened itself and in an act of self- procreation gave birth to An ( Anu ) ( sky god ) and Ki ( goddess of the Earth ), commonly referred to as Ninhursag . Binding of Anu (An) and Ki produced Enlil , Mr. Wind , who eventually became the leader of the gods. Then Enlil was banished from Dilmun (the home of the gods) because of the violation of Ninlil , of which he had a son , Sin ( moon god ) , also known as Nanna . No Ningal and gave birth to Inanna ( goddess of love and war ) and Utu or Shamash ( the sun god ) . -

Asher-Greve / Westenholz Goddesses in Context ORBIS BIBLICUS ET ORIENTALIS

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Goddesses in Context: On Divine Powers, Roles, Relationships and Gender in Mesopotamian Textual and Visual Sources Asher-Greve, Julia M ; Westenholz, Joan Goodnick Abstract: Goddesses in Context examines from different perspectives some of the most challenging themes in Mesopotamian religion such as gender switch of deities and changes of the status, roles and functions of goddesses. The authors incorporate recent scholarship from various disciplines into their analysis of textual and visual sources, representations in diverse media, theological strategies, typologies, and the place of image in religion and cult over a span of three millennia. Different types of syncretism (fusion, fission, mutation) resulted in transformation and homogenization of goddesses’ roles and functions. The processes of syncretism (a useful heuristic tool for studying the evolution of religions and the attendant political and social changes) and gender switch were facilitated by the fluidity of personality due to multiple or similar divine roles and functions. Few goddesses kept their identity throughout the millennia. Individuality is rare in the iconography of goddesses while visual emphasis is on repetition of generic divine figures (hieros typos) in order to retain recognizability of divinity, where femininity is of secondary significance. The book demonstrates that goddesses were never marginalized or extrinsic and thattheir continuous presence in texts, cult images, rituals, and worship throughout Mesopotamian history is testimony to their powerful numinous impact. This richly illustrated book is the first in-depth analysis of goddesses and the changes they underwent from the earliest visual and textual evidence around 3000 BCE to the end of ancient Mesopotamian civilization in the Seleucid period. -

Desire, Discord, and Death : Approaches to Ancient Near Eastern Myth / by Neal Walls

DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH ASOR Books Volume 8 Victor Matthews, editor Billie Jean Collins ASOR Director of Publications DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH by Neal Walls American Schools of Oriental Research • Boston, MA DESIRE, DISCORD AND DEATH APPROACHES TO ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN MYTH Copyright © 2001 American Schools of Oriental Research Cover art: Cylinder seal from Susa inscribed with the name of worshiper of Nergal. Photo courtesy of the Louvre Museum. Cover design by Monica McLeod. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Walls, Neal H., 1962- Desire, discord, and death : approaches to ancient Near Eastern myth / by Neal Walls. p. cm. -- (ASOR books ; v. 8) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0-89757-056-1 -- ISBN 0-89757-055-3 (pbk.) 1. Mythology--Middle East. 2. Middle East--Literatures--History and crticism. 3. Death in literature. 4. Desire in literature. I. Title. II. Series. BL1060 .W34 2001 291.1'3'09394--dc21 2001003236 Contents ABBREVIATIONS vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii INTRODUCTION Hidden Riches in Secret Places 1 METHODS AND APPROACHES 3 CHAPTER ONE The Allure of Gilgamesh: The Construction of Desire in the Gilgamesh Epic INTRODUCTION 9 The Construction of Desire: Queering Gilgamesh 11 THE EROTIC GILGAMESH 17 The Prostitute and the Primal Man: Inciting Desire 18 The Gaze of Ishtar: Denying Desire 34 Heroic Love: Requiting Desire 50 The Death of Desire 68 CONCLUSION 76 CHAPTER TWO On the Couch with Horus and Seth: A Freudian -

The Mesopotamian Netherworld Through the Archaeology of Grave Goods and Textual Sources in the Early Dynastic III Period to the Old Babylonian Period

UO[INOIGMUKJ[ 0LATE The Mesopotamian Netherworld through the Archaeology of Grave Goods and Textual Sources in the Early Dynastic III Period to the Old Babylonian Period A B N $EEP3HAFTOF"URIALIN&OREGROUNDWITH-UDBRICK"LOCKINGOF%NTRANCETO#HAMBERFOR"URIAL 3KELETON ANDO "URIAL 3KELETONNikki Zwitser Promoter: Prof. Dr. Katrien De Graef Co-promoter: Prof. Dr. Joachim Bretschneider Academic Year 2016-1017 Thesis submitted to obtain the degree of Master of Arts: Archaeology. Preface To the dark house, dwelling of Erkalla’s god, to the dark house which those who enter cannot leave, on the road where travelling is one-way only, to the house where those enter are deprived of light, where dust is their food, clay their bread. They see no light, they dwell in darkness. Many scholars who rely on literary texts depict the Mesopotamian netherworld as a bleak and dismal place. This dark portrayal does, indeed, find much support in the Mesopotamian literature. Indeed many texts describe the afterlife as exceptionally depressing. However, the archaeological study of grave goods may suggest that there were other ways of thinking about the netherworld. Furthermore, some scholars have neglected the archaeological data, while others have limited the possibilities of archaeological data by solely looking at royal burials. Mesopotamian beliefs concerning mortuary practices and the afterlife can be studied more thoroughly by including archaeological data regarding non-royal burials and textual sources. A comparison of the copious amount of archaeological and textual evidence should give us a further insight in the Mesopotamian beliefs of death and the netherworld. Therefore, for this study grave goods from non-royal burials, literature and administrative texts will be examined and compared to gain a better understanding of Mesopotamian ideas regarding death and the netherworld. -

Sumerian Liturgies and Psalms

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM PUBLICATIONS OF THE BABYLONIAN SECTION VOL. X No. 4 SUMERIAN LITURGIES AND PSALMS STEPHEN LANGDON PROFESSOROF ASSYRIOLOGY AT OXFORDUNIVERSITY PHILADELPHIA PUBLISHED BY THE UNIVERSITY MUSEUM 1919 DI'IINITY LIBRARY CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION .................................. 233 SUMERIAN LITURGIES AND PSALMS: LAMENTATIONOF ISHME-DAGANOVER NIPPUR ..... LITURGYOF THE CULTOF ISHME-DAGAN.......... LITURGICALHYMN TO INNINI ..................... PSALMTO ENLIL LAMENTATIONON THE PILLAGEOF LAGASHBY THE ELAMITES................................... LAMENTATIONTO ~NNINI ON THE SORROWSOF ERECH. LITURGICALHYMN TO SIN........................ LAMENTATIONON THE DESTRUCTIONOF UR........ LITURGICALHYMNS OF THE TAMMUZCULT ........ A LITURGYTO ENLIL,Elum Gud-Sun ............. EARLYFORM OF THE SERIESd~abbar&n-k-ta .... LITURGYOF THE CULTOF KESH................. SERIESElum Didara, THIRDTABLET .............. BABYLONIANCULT SYMBOLS ...................... INTRODUCTION With the publication of the texts included in this the last part of volume X, Sumerian Liturgical and Epical Texts, the writer arrives at a definite stage in the interpretation of the religious material in the Nippur collection. Having been privi- leged to examine the collection in Philadelphia as well as that in Constantinople, I write with a sense of responsibility in giving to the public a brief statement concerning what the temple library of ancient Nippur really contained. Omitting the branches pertaining to history, law, grammar and mathematics, -

Law (Lltle 17 U.S. Code.) MAIER: the Poetic Uses of Mesopotamian Sc J.J May Not Originally Have Had

MOTIC~: Tb\t Mat.oat MIIj ,. ProteotlG By ~"ghl Law (lltle 17 U.S. Code.) MAIER: The Poetic Uses of Mesopotamian Sc _J.J may not originally have had. Even more striking is his poem, The Maximus Poems. Sumerian and Akkadian treatment of the goddess, Ereshkigal. He avoids the allusions are many and important to these works, but specification, "mother of the god Ninazu," and thus they are not, of course, the only ancient and non reduces the goddess to elemental "mother." There is Western concerns in his works. Olson had a deep some question why Ereshkigal should be described the interest in Mayan culture, for example, and the Mayan way the Sumerian and Akkadian originals portray materials were more accessible to him than Sumero her, but Olson's interpretation makes it clear that he Akkadian materials. Because he does not speak of thinks the mother lying naked, her body uncovered, these matters with immediate reference to his personal her breasts exposed to "you and the judges" is an life and to the political issues of the day, it is difficult image of erotic seduction-more like Inanna than her to say how much personal and political causes help sister. Finally, Olson downplays the "outcry" of the sustain the ancient, mythic images in his writing. nether world, with all its magical properties, and plays Olson declined a political occupation after World up instead an ambiguity in the original. Is Enkidu War II. Certainly he believed that America in the really to be seized "for what you have done; for her"'? post-war era had certain connections with a very The statement, never clarified, suggests a descent to ancient Sumerian civilization. -

The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Historia Religionum 35 The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess An Interpretation of Her Myths Therese Rodin Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihresalen, Tun- bergsvägen 3L, Uppsala, Saturday, 6 September 2014 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Britt- Mari Näsström (Gothenburg University, Department of Literature, History of Ideas, and Religion, History of Religions). Abstract Rodin, T. 2014. The World of the Sumerian Mother Goddess. An Interpretation of Her Myths. Historia religionum 35. 350 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-554- 8979-3. The present study is an interpretation of the two myths copied in the Old Babylonian period in which the Sumerian mother goddess is one of the main actors. The first myth is commonly called “Enki and NinপXUVDƣa”, and the second “Enki and Ninmaপ”. The theoretical point of departure is that myths have society as their referents, i.e. they are “talking about” society, and that this is done in an ideological way. This study aims at investigating on the one hand which contexts in the Mesopotamian society each section of the myths refers to, and on the other hand which ideological aspects that the myths express in terms of power relations. The myths are contextualized in relation to their historical and social setting. If the myth for example deals with working men, male work in the area during the relevant period is dis- cussed. The same method of contextualization is used regarding marriage, geographical points of reference and so on. -

Perceptions of the Serpent in the Ancient Near East: Its Bronze Age Role in Apotropaic Magic, Healing and Protection

PERCEPTIONS OF THE SERPENT IN THE ANCIENT NEAR EAST: ITS BRONZE AGE ROLE IN APOTROPAIC MAGIC, HEALING AND PROTECTION by WENDY REBECCA JENNIFER GOLDING submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject ANCIENT NEAR EASTERN STUDIES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR M LE ROUX November 2013 Snake I am The Beginning and the End, The Protector and the Healer, The Primordial Creator, Wisdom, all-knowing, Duality, Life, yet the terror in the darkness. I am Creation and Chaos, The water and the fire. I am all of this, I am Snake. I rise with the lotus From muddy concepts of Nun. I am the protector of kings And the fiery eye of Ra. I am the fiery one, The dark one, Leviathan Above and below, The all-encompassing ouroboros, I am Snake. (Wendy Golding 2012) ii SUMMARY In this dissertation I examine the role played by the ancient Near Eastern serpent in apotropaic and prophylactic magic. Within this realm the serpent appears in roles in healing and protection where magic is often employed. The possibility of positive and negative roles is investigated. The study is confined to the Bronze Age in ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia and Syria-Palestine. The serpents, serpent deities and deities with ophidian aspects and associations are described. By examining these serpents and deities and their roles it is possible to incorporate a comparative element into his study on an intra- and inter- regional basis. In order to accumulate information for this study I have utilised textual and pictorial evidence, as well as artefacts (such as jewellery, pottery and other amulets) bearing serpent motifs. -

Death They Dispensed to Mankind the Funerary World of Ancient Mesopotamia 1

DEATH THEY DISPENSED TO MANKIND THE FUNERARY WORLD OF ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA 1 DINA KATZ Leiden Inhumation, rather than discarding of the corpse at a safe distance to rot or be devoured by wild animals, is a sign of respect to the human body. The traditional burial practices point to a funerary cult, with variations that suggest differentiation according to socio-economic status. Deposits of grave goods, particularly food, drink and personal belongings, demonstrate a belief that life continues beyond the grave, and therefore that humankind contains an immortal segment. Thus, death appears as a transitional phase, in which life is transformed from one mode to another. Modern readers may perceive it as a passage from an actual to a mythological reality, but the ancient Mesopotamian treated it as a continuous actual reality, in a different mode and location. 2 1Abbreviations used are those of PSD, CAD. Additional are: ETCSL (www.etcsl.orient.ox.ac.uk ) DGil – The death of Gilgameš (Cavigneaux 2000), Urnamma A – The death of Urnamma (Flückiger-Hawker 1999; ETCSL 2.4.1.1), GEN – Gilgameš, Enkidu and the Netherworld (ETCSL 1.8.1.4), Gilg. – The (Akkadian) Epic of Gilgameš (George 2003), ID – Inana’s Descent (ETCSL 1.4.1), IšD – Ištar’s Descent . For reasons of clarity, brackets marking reconstruction of text were omitted from the translations. 2 It is not my intention to present an integrative history. Cultural uniformity has never really been achieved by the ancient Mesopotamian civilizations. Least of all religious practices, which involved official and popular streams. Therefore, one should bear in mind that we deal with a range of individual histories sharing basic principles and different degrees of common features.