Towards a Critical Race Methodology in Algorithmic Fairness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

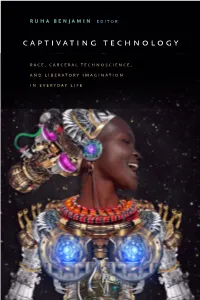

Captivating Technology

Ruha Benjamin editoR Captivating teChnology RaCe, CaRCeRal teChnosCienCe, and libeRatoRy imagination ine ev Ryday life captivating technology Captivating Technology race, carceral technoscience, and liberatory imagination in everyday life Ruha Benjamin, editor Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of Amer i ca on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Kim Bryant Typeset in Merope and Scala Sans by Westchester Publishing Services Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Benjamin, Ruha, editor. Title: Captivating technology : race, carceral technoscience, and liberatory imagination in everyday life / Ruha Benjamin, editor. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: lccn 2018042310 (print) | lccn 2018056888 (ebook) isbn 9781478004493 (ebook) isbn 9781478003236 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478003816 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Prisons— United States. | Electronic surveillance— Social aspects— United States. | Racial profiling in law enforcement— United States. | Discrimination in criminal justice administration— United States. | African Americans— Social conditions—21st century. | United States— Race relations—21st century. | Privacy, Right of— United States. Classification: lcc hv9471 (ebook) | lcc hv9471 .c2825 2019 (print) | ddc 364.028/4— dc23 lc rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2018042310 An earlier version of chapter 1, “Naturalizing Coersion,” by Britt Rusert, was published as “ ‘A Study of Nature’: The Tuskegee Experiments and the New South Plantation,” in Journal of Medical Humanities 30, no. 3 (summer 2009): 155–71. The author thanks Springer Nature for permission to publish an updated essay. Chapter 13, “Scratch a Theory, You Find a Biography,” the interview of Troy Duster by Alondra Nelson, originally appeared in the journal Public Culture 24, no. -

Amazon's Antitrust Paradox

LINA M. KHAN Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox abstract. Amazon is the titan of twenty-first century commerce. In addition to being a re- tailer, it is now a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading host of cloud server space. Although Amazon has clocked staggering growth, it generates meager profits, choosing to price below-cost and ex- pand widely instead. Through this strategy, the company has positioned itself at the center of e- commerce and now serves as essential infrastructure for a host of other businesses that depend upon it. Elements of the firm’s structure and conduct pose anticompetitive concerns—yet it has escaped antitrust scrutiny. This Note argues that the current framework in antitrust—specifically its pegging competi- tion to “consumer welfare,” defined as short-term price effects—is unequipped to capture the ar- chitecture of market power in the modern economy. We cannot cognize the potential harms to competition posed by Amazon’s dominance if we measure competition primarily through price and output. Specifically, current doctrine underappreciates the risk of predatory pricing and how integration across distinct business lines may prove anticompetitive. These concerns are height- ened in the context of online platforms for two reasons. First, the economics of platform markets create incentives for a company to pursue growth over profits, a strategy that investors have re- warded. Under these conditions, predatory pricing becomes highly rational—even as existing doctrine treats it as irrational and therefore implausible. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

1 Statement of Justin Brookman Director, Privacy and Technology Policy Consumers Union Before the House Subcommittee on Digital

Statement of Justin Brookman Director, Privacy and Technology Policy Consumers Union Before the House Subcommittee on Digital Commerce and Consumer Protection Understanding the Digital Advertising Ecosystem June 14, 2018 On behalf of Consumers Union, I want to thank you for the opportunity to testify today. We appreciate the leadership of Chairman Latta and Ranking Member Schakowsky in holding today’s hearing to explore the digital advertising ecosystem and how digital advertisements affect Americans. I appear here today on behalf of Consumers Union, the advocacy division of Consumer Reports, an independent, nonprofit, organization that works side by side with consumers to create a fairer, safer, and healthier world.1 1 Consumer Reports is the world’s largest independent product-testing organization. It conducts its advocacy work in the areas of privacy, telecommunications, financial services, food and product safety, health care, among other areas. Using its dozens of labs, auto test center, and survey research department, the nonprofit organization rates thousands of products and services annually. Founded in 1936, Consumer Reports has over 7 million members and publishes its magazine, website, and other publications. 1 Executive Summary My testimony today is divided into three parts. First, I describe some of the many ways that the digital advertising ecosystem has gotten more complex in recent years, leaving consumers with little information or agency over how to safeguard their privacy. Consumers are no longer just tracked through cookies in a web browser: instead, companies are developing a range of novel techniques to monitor online behavior and to tie that to what consumers do on other devices and in the physical world. -

Julia Angwin

For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] Julia Angwin Topics Journalism, Science and Technology Travels From New York Bio Julia Angwin is an award-winning senior investigative reporter at ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom in New York. From 2000 to 2013, she was a reporter at The Wall Street Journal, where she led a privacy investigative team that was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in Explanatory Reporting in 2011 and won a Gerald Loeb Award in 2010. Her book Dragnet Nation: A Quest for Privacy, Security and Freedom in a World of Relentless Surveillance was shortlisted for Best Business Book of the Year by the Financial Times. Julia is an accomplished and sought-after speaker on the topics of privacy, technology, and the quantified society that we live in. Among the many venues at which she has spoken are the Aspen Ideas Festival, the Chicago Humanities Festival, and keynotes at the Strata big data conference and the International Association of Privacy Professionals. In 2003, she was on a team of reporters at The Wall Street Journal that was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in Explanatory Reporting for coverage of corporate corruption. She is also the author of Stealing MySpace: The Battle to Control the Most Popular Website in America. She earned a B.A. in mathematics from the University of Chicago and an MBA from the page 1 / 3 For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] Graduate School of Business at Columbia University. -

Informed Refusal: Reprints and Permission: Sagepub.Com/Journalspermissions.Nav DOI: 10.1177/0162243916656059 Toward a Justice- Sthv.Sagepub.Com Based Bioethics

Article Science, Technology, & Human Values 1-24 ª The Author(s) 2016 Informed Refusal: Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0162243916656059 Toward a Justice- sthv.sagepub.com based Bioethics Ruha Benjamin1 Abstract ‘‘Informed consent’’ implicitly links the transmission of information to the granting of permission on the part of patients, tissue donors, and research subjects. But what of the corollary, informed refusal? Drawing together insights from three moments of refusal, this article explores the rights and obligations of biological citizenship from the vantage point of biodefectors— those who attempt to resist technoscientific conscription. Taken together, the cases expose the limits of individual autonomy as one of the bedrocks of bioethics and suggest the need for a justice-oriented approach to science, medicine, and technology that reclaims the epistemological and political value of refusal. Keywords ethics, justice, inequality, protest, politics, power, governance, other, engagement, intervention 1Department of African American Studies, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, USA Corresponding Author: Ruha Benjamin, Department of African American Studies, Princeton University, 003 Stanhope Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544, USA. Email: [email protected] Downloaded from sth.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2016 2 Science, Technology, & Human Values In this article, I investigate the contours of biological citizenship from the vantage point of the biodefector—a way of conceptualizing those who resist -

United States

FREEDOM ON THE NET 2016 United States 2015 2016 Population: 321.4 million Internet Freedom Status Free Free Internet Penetration 2015 (ITU): 75 percent Social Media/ICT Apps Blocked: No Obstacles to Access (0-25) 3 3 Political/Social Content Blocked: No Limits on Content (0-35) 2 2 Bloggers/ICT Users Arrested: No Violations of User Rights (0-40) 14 13 TOTAL* (0-100) 19 18 Press Freedom 2016 Status: Free * 0=most free, 100=least free Key Developments: June 2015 – May 2016 ● The USA FREEDOM Act passed in June 2015 limited bulk collection of Americans’ phone records and established other privacy protections. Nonetheless, mass surveillance targeting foreign citizens continues through programs authorized under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act and Executive Order 12333 (see Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). ● Online media outlets and journalists face increased pressure, both financially and politically, that may impact future news coverage (see Media, Diversity, and Content Manipulation). ● Following a terrorist attack in San Bernardino in December 2015, the FBI sought to compel Apple to bypass security protections on the locked iPhone of one of the perpetrators (see Surveillance, Privacy, and Anonymity). www.freedomonthenet.org FREEDOM UNITED STATES ON THE NET 2016 Introduction Internet freedom improved slightly as the United States took a significant step toward reining in mass surveillance by the National Security Agency (NSA) with the passage of the USA FREEDOM Act in June 2015. The law ended the bulk collection of Americans’ phone records under Section 215 of the PATRIOT Act, a program detailed in documents leaked by former NSA contractor Edward Snowden in 2013 and ruled illegal by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in May 2015. -

Fighting Cyber-Crime After United States V. Jones Danielle K

Boston University School of Law Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law Faculty Scholarship Summer 2013 Fighting Cyber-Crime After United States v. Jones Danielle K. Citron Boston University School of Law David Gray University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law Liz Rinehart University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Privacy Law Commons Recommended Citation Danielle K. Citron, David Gray & Liz Rinehart, Fighting Cyber-Crime After United States v. Jones, 103 Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 745 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.bu.edu/faculty_scholarship/625 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Boston University School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fighting Cyber-Crime After United States v. Jones David C. Gray Danielle Keats Citron Liz Clark Rinehard No. 2013 - 49 This paper can be downloaded free of charge at: The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection http://ssrn.com/abstract=2302861 Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 103 | Issue 3 Article 4 Summer 2013 Fighting Cybercrime After United States v. Jones David Gray Danielle Keats Citron Liz Clark Rinehart Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation David Gray, Danielle Keats Citron, and Liz Clark Rinehart, Fighting Cybercrime After United States v. -

34:3 Berkeley Technology Law Journal

34:3 BERKELEY TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL 2019 Pages 705 to 918 Berkeley Technology Law Journal Volume 34, Number 3 Production: Produced by members of the Berkeley Technology Law Journal. All editing and layout done using Microsoft Word. Printer: Joe Christensen, Inc., Lincoln, Nebraska. Printed in the U.S.A. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48—1984. Copyright © 2019 Regents of the University of California. All Rights Reserved. Berkeley Technology Law Journal University of California School of Law 3 Law Building Berkeley, California 94720-7200 [email protected] https://www.btlj.org BERKELEY TECHNOLOGY LAW JOURNAL VOLUME 34 NUMBER 3 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARTICLES THE INSTITUTIONAL LIFE OF ALGORITHMIC RISK ASSESSMENT ............................ 705 Alicia Solow-Niederman, YooJung Choi & Guy Van den Broeck STRANGE LOOPS: APPARENT VERSUS ACTUAL HUMAN INVOLVEMENT IN AUTOMATED DECISION MAKING .................................................................................. 745 Kiel Brennan-Marquez, Karen Levy & Daniel Susser PROCUREMENT AS POLICY: ADMINISTRATIVE PROCESS FOR MACHINE LEARNING ........................................................................................................................... 773 Deirdre K. Mulligan & Kenneth A. Bamberger AUTOMATED DECISION SUPPORT TECHNOLOGIES AND THE LEGAL PROFESSION ....................................................................................................................... -

South San Francisco Public Library Computer Basics Architecture of the Internet

South San Francisco Public Library Computer Basics Architecture of the Internet Architecture of the Internet COOKIES: A piece of data stored on a person’s computer by a website to enable the site to “remember” useful information, such as previous browsing history on the site or sign-in information. • Website cookies explained | Guardian Animations - YouTube ALGORITHMS: A set of instructions to be followed, usually applied in computer code, to carry out a task. Algorithms drive content amplification, whether that’s the next video on YouTube, ad on Facebook, or product on Amazon. Also, the algorithms serve a very specific economic purpose: to keep you using the app or website in order to serve more ads. • Review Facebook’s Ad Policy • Visit Your Ad Choices and run a diagnostic test on your computer or phone FILTER BUBBLES: Intellectual isolation that results from information served primarily through search engines that filter results based on personalized data, creating a “bubble” that isolates the user from information that may not align with their existing viewpoints. • Have Scientists Found a Way to Pop the Filter Bubble? | Innovation | Smithsonian Magazine What can you do to protect yourself? • Visit Electronic Frontier Foundation for tools to protect your online privacy. • Visit FTC.gov for more information on cookies and understanding online tracking Additional Resources • Is your device listening to you? 'Your Social Media Apps are Not Listening to You': Tech Worker Explains Data Privacy in Viral Twitter Thread (newsweek.com) • “Website Cookies Explained | The Guardian Animations” South San Francisco Public Library Computer Basics Architecture of the Internet • “How Recommendation Algorithms Run The World,” Wired. -

Cultural Inversion and the One-Drop Rule: an Essay on Biology, Racial Classification, and the Rhetoric of Racial Transcendence

05 POST.FINAL.12.9.09.DOCX 1/26/2010 6:50 PM CULTURAL INVERSION AND THE ONE-DROP RULE: AN ESSAY ON BIOLOGY, RACIAL CLASSIFICATION, AND THE RHETORIC OF RACIAL TRANSCENDENCE Deborah W. Post The great paradox in contemporary race politics is exemplified in the narrative constructed by and about President Barack Obama. This narrative is all about race even as it makes various claims about the diminished significance of race: the prospect of racial healing, the ability of a new generation of Americans to transcend race or to choose their own identity, and the emergence of a post- racial society.1 While I do not subscribe to the post-racial theories 1 I tried to find the source of the claims that Obama “transcends” race. There are two possibilities: that Obama is not identified or chooses not to identify as a black man but as someone not “raced” and/or that Obama is simply able to overcome the resistance of white voters who ordinarily would not be inclined to vote for a black man. While these sound as if they are the same, they are actually different. If the entire community, including both whites and blacks, no longer see race as relevant, then the reference to “transcendence” or to a “post- racial” moment in history is probably appropriate. If, however, the phenomenon we are considering is simply the fact that some whites no longer consider race relevant in judging who is qualified, if racial bias or animus has lost some of its force, then race may still be relevant in a multitude of ways important to both whites and blacks. -

UNI Quest for Racial Equity Project

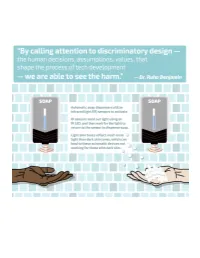

Race to the Future? Reimagining the Default Settings of Technology & Society University of Northern Iowa - Quest for Racial Equity Project Dr. Ruha Benjamin, Princeton University Professor of African American Studies, primarily researches, writes, and speaks on the intersection of technology with health, equity, and justice. She is the author of: Race After technology: Abolitionist Tools for the Next Jim Code and People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem cell Frontier. In this 35-minute presentation, Dr. Benjamin discusses and provides examples of how the design and implementation of technology has intended and unintended consequences which support systematic racism. She asks the audience to imag- ine a world in which socially conscious approaches to technology development can intentionally build a more just world. Your Tasks: • Watch Race to the Future? Reimagining the default settings of technology and society, Dr. Ruha Benjamin’s presentation from the 2020 NCWIT Conversations for Change Series. (https://www.ncwit.org/video/race-future-reimagining-default-settings-technology-and-society-ruha-benjamin-video-playback) • Together with 1 or 2 other Quest participants, have a discussion using one or more of the question groups below. If you are questing on your own, choose 2-3 questions and journal about each question you choose for 7 minutes. • Finally, make a future technology pledge. Your pledge could be about questioning new technologies, changing your organization's policies about technology adoption, or something else. Questions