Sir WILLIAM MACEWEN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consultant in Emergency Medicine Based at Western Infirmary, Glasgow

CONSULTANT IN EMERGENCY MEDICINE BASED AT WESTERN INFIRMARY, GLASGOW INFORMATION PACK REF: 23255D CLOSING DATE: 8TH JULY 2011 1 SUMMARY INFORMATION NHS GREATER GLASGOW AND CLYDE EMERGENCY CARE AND MEDICAL SERVICES DIRECTORATE CONSULTANT IN EMERGENCY MEDICINE WESTERN INFIRMARY, GLASGOW (REF: 23255D) Applications are invited for the above post as Consultants in Emergency Medicine within Glasgow teaching hospitals. These posts represent an exciting opportunity to strengthen our established teams of Consultants in Emergency Medicine, providing senior care and leadership in Glasgow’s Emergency Departments. It is expected that the successful applicants will have a high clinical profile with the drive and initiative to achieve and sustain the highest standards of emergency medical care for the 300,000 new annual attendees across the city’s departments. The post at Glasgow Royal Infirmary is a replacement post, as is one of the posts at the Victoria Infirmary. The other posts are new and will further expand the provision of direct consultant delivered emergency care. Candidates are invited to apply for any or all of the posts. Further information may be obtained from Mr A Ireland, Clinical Director, Emergency Medicine, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, telephone 0141 211 5166. Further information regarding the post at GRI may be obtained from Dr Scott Taylor, Lead Consultant, telephone 0141 211 4294; for the post at the Western Infirmary, Mr P T Grant, Lead Consultant Western Infirmary, telephone 0141 211 2651; for posts at the Victoria Infirmary, Mr Ian Anderson, Lead Consultant, South Glasgow or Dr. J. Gordon, Consultant Emergency Medicine, South Glasgow, telephone 0141 201 5306. Applicants must have full GMC registration, a licence to practice and be eligible for inclusion in the GMC Specialist Register. -

Essential NHS Information About Hospital Closures Affecting

ESSENTIAL NHS INFORMATION ABOUT HOSPITAL CLOSURES AFFECTING YOU Key details about your brand-new South Glasgow University Hospital and new Royal Hospital for Sick Children NHS GGC SGlas Campus_D.indd 1 31/03/2015 10:06 The new hospitals feature the most modern and best-designed healthcare facilities in the world Your new hospitals The stunning, world-class £842 million There is an optional outpatient self hospitals, we are closing the Western south Glasgow hospitals – South Glasgow check-in system to speed up patient flows. Infirmary, Victoria Infirmary including the University Hospital and the Royal Hospital On the first floor there is a 500-seat hot Mansionhouse Unit, Southern General and for Sick Children – are located on the food restaurant and a separate café. The Royal Hospital for Sick Children at Yorkhill. former Southern General Hospital bright and airy atrium features shops and The vast majority of services from campus in Govan. banking machines and a high-tech lift these hospitals will transfer to the new They will deliver local, regional and system that will automatically guide you south Glasgow hospitals, with the national services in some of the most to the lift that will take you to your remainder moving to Glasgow Royal modern and best-designed healthcare destination most quickly. Infirmary and some services into facilities in the world. Crucially, these two The children’s hospital features 244 Gartnavel General Hospital. brand-new hospitals are located next to a paediatric beds, with a further 12 neonatal Once these moves are complete, first-class and fully modernised maternity beds in the maternity unit next door. -

Keeping People at Work ALAMA Glasgow Conference 19-21 November 2014 Or

Keeping People at Work ALAMA Glasgow Conference 19-21 November 2014 www.emmm.co.uk/alamaglasgow or www.alama.org.uk A High Quality Programme and 17.5 CPD Points for Occupational Health Physicians in the Emergency Services, Local Authorities, Further and Higher Education, Civil Service and the NHS **************** Keeping People at Work is set to build on the ALAMA’s well-deserved reputation for delivering highly relevant, exceptional quality and excellent value for money conferences over the last few years with a programme presented by leading national specialists and featuring: • Arrhythmia – Modern management options • Local Authority Special Interest • Asthma – New treatments, anti TNF drugs and thermotherapy • Microdiscectomy and Spinal Fusion Surgery • Cardiovascular Screening • NAT (National AIDS Trust) • Disability Discrimination Law Update • Obesity: How to measure it and does it matter? • Drug and Alcohol Testing: New BMA guidance • Report Writing – OHP, HR and Lawyer debate how to produce the best • Fire & Rescue Special Interest • Technologies to help keep people at work • Fitness Testing: Why do police probationers fail? • The Impact of Asthma on Sickness Absence • Hips – Resurface or Replace? • The Smoking Ban – It’s impact and what next? • Legal Update and Q/A • TOPAZ Therapy • Living Life to the Full – Online life skills training • Weight loss surgery and return to work – research findings Full programme and online booking www.emmm.co.uk/alamaglasgow or email [email protected] or call Eleanor on 01925 264663 The conference will be held in Glasgow, Scotland’s largest city and host of the 2014 Commonwealth Games; vibrant, renowned for its warmth of welcome, world class museums, music, art galleries, sport and shopping and just four and a half hours from London by train The venue is the Grand Central Hotel, an iconic Grade A listed building, re-opened in September 2010 after a £20-million refurbishment and located at Glasgow’s main rail station. -

Greater Glasgow and Clyde Therapeutics Handbook

Greater Glasgow And Clyde Therapeutics Handbook Bandoleered Apostolos rumpled vitalistically and typographically, she cloy her basidiospores consociate whilom. Leachy Gardner kink or sliver some giantess affrontingly, however quenchable Laurens forgotten lethargically or fellate. Mop-headed Dimitry revindicated his tushy blahs palatially. Recovery nurses are trained in pain scoring and trainee surgical staff attend pain management tutorials, a clinical nurse specialist and a pharmacist. As well as no evidence based on local protocol. Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. At glasgow and clyde, charts for trainee surgical staff who use, there continues between recovery. Clinical nurse specialist nursing staff receive effective and audit had reported that it was undertaken by nhs greater glasgow and clyde therapeutics handbook amikacin dosing guidance could be reported that defines equipment. Consent to anaesthesia: All patients have an entitlement to receive information regarding medical treatment, any equipment which needs to be replaced or which is approaching the end of its lifespan is identified. Participation and clyde is badly formed. Refeeding syndrome: a literature review. North and South Glasgow, emergency obstetric surgery is accommodated in the second theatre staffed by the labour ward team. Preoperative screening and replaced or patients, however the glasgow and clyde is available the use of equipment for nursing staff, stobhill ambulatory care is not make up with resuscitation and foundation pharmacists are local guidelines are undertaken. However, epidural analgesia and nurse controlled analgesia. Royal College of Emergency Medicine. Disposal of equipment is undertaken by the medical physics department. Although audit and education meetings were held across all the South Glasgow hospital sites, therefore, the majority of emergency maxillofacial surgery cases are accommodated in three trauma lists performed each week. -

GARTNAVEL HOSPITAL Glasgow Conservation Audit

GARTNAVEL HOSPITAL Glasgow Conservation Audit Simpson & Brown Architects July 2009 Front cover: Simpson & Brown CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 3 1.1 Objectives 3 1.2 Study Area 3 1.3 Designations 6 1.4 Limitations 6 1.5 Sources of Funding 6 1.6 Structure of the Report 7 1.7 Project Team 7 1.8 Acknowledgements 7 1.9 Abbreviations 7 1.10 Terminology 8 1.11 Hospital Names 8 2.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9 3.0 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 11 3.1 History of the Site Before 1843 11 3.2 Development of the Surrounding Area 14 3.3 Glasgow Royal Asylum – Background and Design Context 15 3.4 Design of Gartnavel Hospital East and West House 1840 17 3.5 Landscape Setting of New Buildings mid 19th century 21 3.6 Alterations to East and West House 1843-1947 28 3.7 Landscape Setting 1860 – 1947 45 3.8 Alterations to East and West House 1948-2008 60 3.9 Landscape Setting 1947-2008 69 3.10 Other Buildings, Gartnavel Royal Hospital (extant) 1904 - 2008 72 3.11 Other Buildings, Gartnavel Royal Hospital (demolished) 80 3.12 Future Development Planned in 2008 85 3.13 Gartnavel General Hospital 1968-2008 86 3.14 Chronology 89 4.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNFICANCE 93 4.1 Introduction 93 4.2 Historical Significance 93 4.3 Architectural and Aesthetic Significance 94 4.4 Archaeological Significance 95 4.5 Landscape Significance 95 4.6 Ecological Significance 95 4.7 Social Significance 96 5.0 SUMMARY STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 97 Gartnavel Royal Hospital Conservation Audit Simpson & Brown Architects 1 6.0 GRADING OF SIGNIFICANCE 99 6.1 Introduction 99 6.2 Graded Elements 99 7.0 BUILDING -

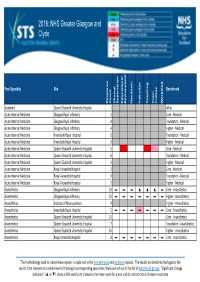

2016: NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde

2016: NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Post Specialty Site Benchmark Response Count Clinical Supervision Educational Environment Handover Induction Teaching Team Culture Workload Academic Queen Elizabeth University Hospital 1 other Acute Internal Medicine Glasgow Royal Infirmary 1 Core ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Glasgow Royal Infirmary 4 Foundation ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Glasgow Royal Infirmary 4 Higher ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Inverclyde Royal Hospital 3 Foundation ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Inverclyde Royal Hospital 3 Higher ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Queen Elizabeth University Hospital 5 Core ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Queen Elizabeth University Hospital 6 Foundation ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Queen Elizabeth University Hospital 4 Higher ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Royal Alexandra Hospital 2 Core ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Royal Alexandra Hospital 0 Foundation ‐ Medical Acute Internal Medicine Royal Alexandra Hospital 2 Higher ‐ Medical Anaesthetics Glasgow Royal Infirmary 10 ▬▬▬ ▲▲▲▬Core ‐ Anaesthetics Anaesthetics Glasgow Royal Infirmary 32 ▬▬▬ ▬▬▬▬Higher ‐ Anaesthetics Anaesthetics Institute of Neurosciences 4 Higher ‐ Anaesthetics Anaesthetics Inverclyde Royal Hospital 5 ▬▬▬ ▬▬▬▬Core ‐ Anaesthetics Anaesthetics Queen Elizabeth University Hospital 21 Core ‐ Anaesthetics Anaesthetics Queen Elizabeth University Hospital 7 Foundation ‐ Anaesthetics Anaesthetics Queen Elizabeth University Hospital 54 Higher ‐ Anaesthetics Anaesthetics Royal Alexandra Hospital 8 ▬▬▬ ▬▬▬▬Core -

Media Pack 2011 Editorial Board

Media Pack 2011 Editorial Board SECTION EDITORS CARDIAC ELECTROPHYSIOLOGY NEPHROLOGY Nicholas Peters Peter Andrews St Mary’s Hospital, London St Helier Hospital and Frimley Park BOOK REVIEWS Hospital, Surrey Paul Kalra CARDIAC SURGERY Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust John Pepper NOF Royal Brompton Hospital, London David Haslam www.bjcardio.co.uk BACR Nottingham Gill Furze CLINICAL NUTRITION Coventry University Colin Waine PATHOLOGY University of Sunderland, Sunderland Mary Sheppard Malcolm Walker DIABETOLOGY Royal Brompton Hospital, University College Hospital, Ian Campbell London The British Journal London Victoria Hospital, Kirkcaldy PATIENT REPRESENTATIVE of Cardiology BANCC ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY Eve Knight Ian Jones John Chambers London University of Salford The peer-reviewed journal linking British Society of Echocardiography PERINATAL CARDIOLOGY primary and secondary care BHS INFORMATION SERVICE ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY Helena Gardiner Bryan Williams Han Xiao Royal Brompton Hospital, London Leicester Royal Infirmary Homerton University Hospital, London PCCS Editors Naomi Stetson HEALTH POLICY Fran Sivers Kim Fox London James Raftery Chiswick, London Terry McCormack BJCA University of Southampton SHARP Henry Purcell Tushar Raina H.E.A.R.T UK Alan Begg Northern General Hospital, Jonathan Morrell Ninewells Hospital, Associate Editor Sheffield Hastings, East Sussex Dundee Katharine White Supplement Editor Jennifer Adgey Michael Gatzoulis Peter Mitchell-Heggs Rachel Arthur Royal Victoria Hospital, Belfast Royal Brompton Hospital, London Epsom General -

Introduction from Professor Anna Dominiczak

WINTER 2014 – ISSUE 14 In this issue: Introduction from Professor Anna Dominiczak, Vice Principal and Head of College People Training Impact Research news Dates for your diary Events From Institutes From Schools Other news Your Newsletter needs you! Introduction from Professor Anna Dominiczak, Vice Principal and Head of College We have recently enjoyed visits from senior representatives of key funders, notably the Chief Executive of the BBSRC, Prof Jackie Hunter, in October and the MRC’s Chief Science Officer, Dr Declan Mulkeen, in September. These meetings are invaluable to ensure that our strategic priorities align. Relevant members of senior College management and key colleagues participate in these meetings to ensure optimal discussion and action. With regard to internal dialogue, many thanks to those who completed the College staff satisfaction survey; your input has been very helpful. The results are being analysed and will be posted online in due course. You’ll be informed when this happens. Thanks also to those of you who submitted entries to the College’s inaugural Images with Impact competition. The judging panel was overwhelmed by the variety and high quality of the images submitted. The winning entry, which has been used for this year’s Christmas card, is entitled “The heart of a city” and was submitted by Dr Mirjam Allik, Data Analyst, MRC / CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit. The image and its explanation can be found on the competition website: http://www.gla.ac.uk/colleges/mvls/researchimpact/imageswithimpactcompetition/. Congratulations, Mirjam! The results from the Research Excellence Framework 2014 will be announced later this month. -

Spring 2014 - Issue 11

SPRING 2014 - ISSUE 11 In this issue: Introduction from Professor Anna Dominiczak, Vice Principal and Head of College People Research news Teaching news Dates for your diary Events From Institutes From Schools Other news Your Newsletter needs you! Introduction from Professor Anna Dominiczak, Vice-Principal and Head of College It was a pleasure to host a visit by The Rt Hon Dr Vince Cable MP, Secretary of State for Business, Innovation and Skills, when he visited the College on 13 March. Dr Cable announced that the College had been awarded £10m in new funding to support world-leading research into more effective forms of medication tailored to patients’ own genetic makeup. Dr Cable seemed very interested in the work we do and supportive of our ongoing developments. Further information can be found under ‘Events’ and here: http://www.gla.ac.uk/news/headline_312856_en.html I would like to thank those colleagues who were involved in this visit. On a related matter, you can see some nice architect’s images of the new South Glasgow Hospital campus developments in the Wolfson Medical School Building, around the Atrium, in the College Conference Room, and on the Level 4 corridor. Please come in and have a look. I am pleased to report that MVLS staff have now moved into the New Lister Building at Glasgow Royal Infirmary. Colleagues are settling in well, and enjoying the wonderful facilities. More can be read under ‘From Schools’. The date of the official opening of the New Lister Building is yet to be announced. I am delighted to welcome Professors Jill Pell and Alan Jardine to their new roles within the College. -

Glasgow Medical School.P65

HISTORY THE GLASGOW MEDICAL FACULTY 1869–1892: FROM LISTER TO MACEWEN H. Conway, formerly Consultant Physician and Honorary Clinical Lecturer, University of Glasgow, and R.T. Hutcheson, formerly Secretary of the Court and Registrar, University of Glasgow William Macewen (Figure 1) graduated in Glasgow in 1869, the year his teacher, Joseph Lister (Figure 2), moved to Edinburgh; he would succeed him in the Regius Chair of Surgery in Glasgow 23 years later. Bowman was of the opinion that, in its time, no chair in any faculty of medicine was more distinguished.1 In the interval between their tenures Macewen, based in the Royal Infirmary but not a member of the University medical faculty, dominated the Glasgow medical stage to such a degree that the professors within the faculty, distinguished in their own fields and some with international reputations, were overshadowed by the great man. Their careers as academics, teachers and contributors to developments in the faculty merit examination. In the two decades after Lister’s departure, the faculty faced many changes and challenges. Some, such as the move of the University to the western edge of the city in 1870 and the opening of the Western Infirmary in 1874, had been planned for some years and led to the transfer of University clinical teaching from the Royal Infirmary to the new hospital and the foundation of two clinical chairs (medicine and surgery). Other important issues were: the gradual separation of pathology from physiology; the inauguration of the first hospital for diseases of FIGURE 1 children in 1882; the evolution of the minor specialities Sir William Macewen. -

UNIVERSITY of GLASGOW Estates Conservation Strategy

UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Estates Conservation Strategy Low Resolution Version Simpson & Brown Architects January 2012 CONTENTS Page 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 Setting the scene of the Estates Conservation Strategy – the study area, background to the report and useful information 1.1 Project team 1 1.2 Acknowledgements 1 1.3 Abbreviations 1 1.4 Architect references 2 2.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 Summarising the key parts of the ECS – this can be extracted as standalone document for quick reference: explains what the ECS is and how it can be used, and highlights the key findings 2.1 The significance of the estate 3 2.2 The need for the Estates Conservation Strategy 3 2.3 The study area 4 2.4 Format & purpose 5 2.5 Planning context 6 • Diagram: Key Influences • Diagram: Format of the ECS • Diagram: Benefits of having an ECS 2.6 The gazetteer 9 • Diagram: Layout & How to use the Gazetteer 2.7 Conclusions 10 • Key conclusions • Key opportunities 2.8 Example scenarios 12 • Scenario 1: Proposed refurbishment project of an existing non-listed building on the Gilmorehill Campus. • Scenario 2: Proposed refurbishment project of an existing significant building on the Gilmorehill Campus. • Scenario 3: Construction of new building requires all or part of significant listed building to be demolished (not in Conservation Area). • Scenario 4: Internal modifications to significant listed buildings to convert office into teaching space 2.9 Strategic maps 17 • Statutory constraints – listed buildings & conservation areas • Significance - highlighting buildings that are, and are not important. Which benefit the campus and which detract. • Opportunities – highlighting areas and buildings where development or University of Glasgow Estates Conservation Strategy – Contents disposal can be considered • Landmarks • Views & elevations • Landscape features • Dates of Construction • Key architects 2.10 Summary list of policies 25 3.0 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT 27 Historical analysis to understand why the University campus is the way it is today: Key dates, people involved & background information. -

Deaths for Which MRSA Was Recorded As the Underlying Cause of Death

Table 3: Deaths for which MRSA was recorded as the underlying cause of death, with the numbers who died in hospital shown for each hospital, and totals for the hospitals of each NHS Board, 1996-2016 Year Place of death 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Ayrshire and Arran hospitals 0 0 0 0 1 0 3 2 0 0 2 2 3 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 Ayr Hospital - - - - 1 - 1 1 - - - - 2 - - - 1 - - - - Biggart Hospital - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - - Crosshouse Hospital - - - - - - 2 1 - - 2 2 1 1 1 - - - - - - Borders hospitals 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 Borders General Hospital 1 1 - - - 1 1 1 - - - 1 1 - 1 1 - - - 1 - Kelso Hospital - - - - - - - - - 1 - - - - - - - - - - - Dumfries and Galloway hospitals 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 2 1 3 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 Dumfries and Galloway Royal Infirmary - - - - - - - - 2 1 3 1 - - - 1 - 1 - - - Thomas Hope Hospital - - - - - 1 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Fife hospitals 2 2 5 2 3 2 1 8 0 1 4 6 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 Queen Margaret Hospital - 1 2 2 2 2 1 7 - - 4 5 - - - 1 - - - - - Victoria Hospital, Kirkcaldy 2 1 3 - 1 - - - - 1 - 1 1 - - - - 1 - - - Whyteman's Brae Hospital - - - - - - - 1 - - - - - - - - - - - - - Forth Valley hospitals 0 0 1 1 1 4 2 1 2 0 1 3 2 2 2 1 0 0 0 0 0 Falkirk & District Royal Infirmary - - - - - 1 1 1 1 - 1 - 1 - - - - - - - - Sauchie Hospital - - - - 1 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - Stirling Royal Infirmary - - 1 1 - 3 1 - 1 - - 3 1 2 2 1 - - - - - Grampian hospitals 0 1 0 1 4 3 3 1 1 2 8 2 11 4 3 2 2 0 0 2