The Path V3 N7 October 1888

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drishti IAS Coaching in Delhi, Online IAS Test Series & Study Material

Drishti IAS Coaching in Delhi, Online IAS Test Series & Study Material drishtiias.com/printpdf/uttar-pradesh-gk-state-pcs-english Uttar Pradesh GK UTTAR PRADESH GK State Uttar Pradesh Capital Lucknow Formation 1 November, 1956 Area 2,40,928 sq. kms. District 75 Administrative Division 18 Population 19,98,12,341 1/20 State Symbol State State Emblem: Bird: A pall Sarus wavy, in Crane chief a (Grus bow–and– Antigone) arrow and in base two fishes 2/20 State State Animal: Tree: Barasingha Ashoka (Rucervus Duvaucelii) State State Flower: Sport: Palash Hockey Uttar Pradesh : General Introduction Reorganisation of State – 1 November, 1956 Name of State – North-West Province (From 1836) – North-West Agra and Oudh Province (From 1877) – United Provinces Agra and Oudh (From 1902) – United Provinces (From 1937) – Uttar Pradesh (From 24 January, 1950) State Capital – Agra (From 1836) – Prayagraj (From 1858) – Lucknow (partial) (From 1921) – Lucknow (completely) (From 1935) Partition of State – 9 November, 2000 [Uttaranchal (currently Uttarakhand) was formed by craving out 13 districts of Uttar Pradesh. Districts of Uttar Pradesh in the National Capital Region (NCR) – 8 (Meerut, Ghaziabad, Gautam Budh Nagar, Bulandshahr, Hapur, Baghpat, Muzaffarnagar, Shamli) Such Chief Ministers of Uttar Pradesh, who got the distinction of being the Prime Minister of India – Chaudhary Charan Singh and Vishwanath Pratap Singh Such Speaker of Uttar Pradesh Legislative Assembly, who also became Chief Minister – Shri Banarsidas and Shripati Mishra Speaker of the 17th Legislative -

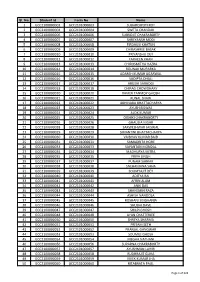

1 Gcc2100000003 Gcc2101000003 Subhrojyoti Roy 2

Sl. No. Student Id Form No Name 1 GCC2100000003 GCC2101000003 SUBHROJYOTI ROY 2 GCC2100000004 GCC2101000004 SWETA CHANDAK 3 GCC2100000006 GCC2101000006 SUBROJIT CHAKRABORTY 4 GCC2100000007 GCC2102000007 SHREYANSH MODI 5 GCC2100000008 GCC2101000008 FIRDAUSI KHATUN 6 GCC2100000009 GCC2101000009 CHIRASHREE BASAK 7 GCC2100000010 GCC2101000010 PRIYANSHU DEY 8 GCC2100000012 GCC2101000012 FARHEEN KHAN 9 GCC2100000013 GCC2101000013 CHIROSMITHA HAZRA 10 GCC2100000014 GCC2101000014 ROUNAK MURARKA 11 GCC2100000015 GCC2101000015 ADARSH KUMAR AGARWAL 12 GCC2100000016 GCC2101000016 SUDIPTA DHALI 13 GCC2100000017 GCC2101000017 ARUSHI SARAOGI 14 GCC2100000018 GCC2101000018 CHIRAG CHOWDHARY 15 GCC2100000020 GCC2101000020 XAVIER TANMOY GHOSH 16 GCC2100000021 GCC2101000021 KUNAL SHAW 17 GCC2100000022 GCC2101000022 ABHINABA BHATTACHARYA 18 GCC2100000023 GCC2101000023 AYUSH BISWAS 19 GCC2100000024 GCC2101000024 ALOK KUMAR 20 GCC2100000025 GCC2101000025 OISHIKI CHAKRABORTY 21 GCC2100000026 GCC2101000026 GHAUSIA NIGAR 22 GCC2100000028 GCC2101000028 SARWESHWAR JAISWAL 23 GCC2100000029 GCC2101000029 SIMANTINI BHATTACHARYA 24 GCC2100000030 GCC2101000030 VAIBHAV KUMAR BAID 25 GCC2100000031 GCC2101000031 SAMADRITA HORE 26 GCC2100000033 GCC2101000033 SAYANTAN MONDAL 27 GCC2100000034 GCC2101000034 MADHURYA MITRA 28 GCC2100000035 GCC2101000035 PRIYA SINGH 29 GCC2100000037 GCC2101000037 PUNAM SARKAR 30 GCC2100000038 GCC2101000038 SNEHANJANA SAHA 31 GCC2100000039 GCC2101000039 SOUMYAJIT DEY 32 GCC2100000040 GCC2101000040 ADITYA RAI 33 GCC2100000041 GCC2101000041 AFRIN -

Editors Seek the Blessings of Mahasaraswathi

OM GAM GANAPATHAYE NAMAH I MAHASARASWATHYAI NAMAH Editors seek the blessings of MahaSaraswathi Kamala Shankar (Editor-in-Chief) Laxmikant Joshi Chitra Padmanabhan Madhu Ramesh Padma Chari Arjun I Shankar Srikali Varanasi Haranath Gnana Varsha Narasimhan II Thanks to the Authors Adarsh Ravikumar Omsri Bharat Akshay Ravikumar Prerana Gundu Ashwin Mohan Priyanka Saha Anand Kanakam Pranav Raja Arvind Chari Pratap Prasad Aravind Rajagopalan Pavan Kumar Jonnalagadda Ashneel K Reddy Rohit Ramachandran Chandrashekhar Suresh Rohan Jonnalagadda Divya Lambah Samika S Kikkeri Divya Santhanam Shreesha Suresha Dr. Dharwar Achar Srinivasan Venkatachari Girish Kowligi Srinivas Pyda Gokul Kowligi Sahana Kribakaran Gopi Krishna Sruti Bharat Guruganesh Kotta Sumedh Goutam Vedanthi Harsha Koneru Srinath Nandakumar Hamsa Ramesha Sanjana Srinivas HCCC Y&E Balajyothi class S Srinivasan Kapil Gururangan Saurabh Karmarkar Karthik Gururangan Sneha Koneru Komal Sharma Sadhika Malladi Katyayini Satya Srivishnu Goutam Vedanthi Kaushik Amancherla Saransh Gupta Medha Raman Varsha Narasimhan Mahadeva Iyer Vaishnavi Jonnalagadda M L Swamy Vyleen Maheshwari Reddy Mahith Amancherla Varun Mahadevan Nikky Cherukuthota Vaishnavi Kashyap Narasimham Garudadri III Contents Forword VI Preface VIII Chairman’s Message X President’s Message XI Significance of Maha Kumbhabhishekam XII Acharya Bharadwaja 1 Acharya Kapil 3 Adi Shankara 6 Aryabhatta 9 Bhadrachala Ramadas 11 Bhaskaracharya 13 Bheeshma 15 Brahmagupta Bhillamalacarya 17 Chanakya 19 Charaka 21 Dhruva 25 Draupadi 27 Gargi -

Book-1-First Page.DOC

(Satyopanisad) ( ): . (Anil Kumar Kamaraju) : (T.Padma) (T.R.Dutta) ( ) (Bro.T.H.Chiew) 1) -------------------------------------------------- 1 2) ----------------------------------------------- 4 3) ( ) --------------------------- 11 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 12 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 33 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 61 4) ----------------------- 78 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 79 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 107 ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 133 Prasthanatraya( Prasthana traya ) (Upanishad) (Brahmasutras) (Bhaga- vadgita) (Veda) (Karma) (Bhakti) (Jnana) Upanishad Upa Ni Shad Upanishad Upanishad Upanishad ( ) (Kodaikanal) (Upanishad) (Upanishad) Satyopanishad ( ) Satyopanishad ( ) (Upanishad) 1 (R.W.Emerson 1803 1882 ) (Atman ) (Veda) Amrtasya putrah ( ) divyatmasvarupulara( ) Upanishad (Swami Vivekananda ) Satya- bodhaka ( Sathya bodhaka ) (Mantra) (Veda) Satyopanisad( ) (Tamil) (Mala- 2 yalam) (Kannada) (Telugu) Satyopanisad ( ) Satya ( ) 1983 (Gurupurnima) · · (Anil Kumar Kamaraju) 3 Satyopanisad ( ) (Telugu) Satyo- panisad Satyopanisad ( ) 4 Satyopanisad (Sakara) (Nirakara) (Purusartha Purus artha ) (I - glasses) ( in-viroment) (Proper-ties) (Atma-sphere) Upanishad ( ) Satyopanisad( ) Samskrti( ) Sadhaka( ) Sadhana ( ) Samskrti ( ) (Vedanta) Satya ( ) (Swami Vivekananda ) 5 (John Hislop) (Rama) (Krishna) (Satya Sai Baba) (Buddha) (Nirvana) ( T.s. Eliot ) ( Macbeth ) (Prof. Samuel Sandweiss) Saichiatry Psychiatry Sadhaka ( ) 6 (Sisyphus) Sadhaka( ) Maya( ) tadatmya ( ) anubhavajnana( ) (Kali Yuga) (P.B.Shelley 1792 1822 ) (Swami Viveka- nanda ) Sadhana( ) Sad -hana( ) Sankalpa ( ) (Sankalpa) -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 3

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) blank DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 3 First Edition Compiled by VASANT MOON Second Edition by Prof. Hari Narake Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 3 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : 14 April, 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. -

Pancha Maha Bhutas (Earth-Water-Fire-Air-Sky)

1 ESSENCE OF PANCHA MAHA BHUTAS (EARTH-WATER-FIRE-AIR-SKY) Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda-Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‗Upanishad Saaraamsa‘ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities Essence of Manu Smriti- Quintessence of Manu Smriti- Essence of Paramartha Saara; Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskra; Essence of Maha Narayanopashid; Essence of Maitri Upanishad Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi; Essence of Bhagya -Bhogya-Yogyata Lakshmi Essence of Soundarya Lahari*- Essence of Popular Stotras*- Essence of Pratyaksha Chandra*- Essence of Pancha Bhutas* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

ESSENCE of TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1

ESSENCE OF TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1 ( KRISHNA YAJURVEDA) BY V. D. N. RAO 1 Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda- Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence -

YOGANANDA with Personal Reflections & Reminiscences

YOGANANDA WITH PERSONAL REFLECTIONS & REMINISCENCES A Biography swami kriyananda 2 PRAISE FOR Paramhansa Yogananda, A Biography 2 “ This new biography of Paramhansa Yogananda will pave the path to perfection in the spiritual journey of each individual. It is a masterpiece that serves as a guide in daily life. Through the stories of his life and the unfolding of his destiny, Yogananda’s life story will inspire the reader and flower a spiritual awakening in every heart.” —Vasant Lad, BAM&S, MASc, Ayurvedic Physician, author of Ayurveda: Science of Self-Healing, Textbook of Ayurveda series, and more “ Through this biography of Paramhansa Yogananda, people will discover their divine nature and potential.” —Bikram Choudhury, Founder of Bikram’s Yoga College of India, author of Bikram Yoga “ A deeply insightful look into the life of one of the greatest spiritual figures of our time, by one of his most accomplished, yet last-remaining living disciples. Like the life it depicts, this book is a gem!” —Walter Cruttenden, author of Lost Star of Myth and Time “ Swami Kriyananda’s biography is a welcome addition to the growing literature on Paramhansa Yogananda. Yogananda was a true seer and indeed, his words ‘shall not die.’” —Amit Goswami, PhD, quantum physicist and author of The Self-Aware Universe, Creative Evolution, and How Quantum Activism can Save Civilization “ In this wonderful new work, we are treated to an intimate portrait of Yogananda’s quick wit and profound wisdom, his challenges and his triumphs. We see his indomitable spirit dealing with shattering betrayals and his perseverance in his goal of establishing a spiritual mission that has enriched the world. -

5. Upanishad Saram

SrIH UbhayavedAnta granthamAlA Upanishad sAram Translation into English by SrI Oppiliappan Kovil VaradachAri SaThakopan from the Tamil mUlam by SrI u. vE. abhinava deSikan, Uttamur VeeraraghavachAriyar SvAmi Sincere Thanks to: 1) SrI u. vE. Abhinava deSika, UttamUr VeeraraghavachAriyar SvAmi Trust for their gracious permission to translate the Tamil original manuscript into English. 2) SrI Srinivasan Narayanan SvAmi for proof-reading and formatting the English text 3) SrI Srikanth Veeraraghavan for liaison with the Trust authorities regarding the book 4) Smt Jayashree Muralidharan for Cover design and book assembly. 2 CONTENTS About SrI “abhinava dESika” UttamUr Tirumalai “VAtsya” VeerarAghavAchArya SvAmi Introduction by SrI Oppliappan Kovil, V. Sadagopan Introduction by SrI. u. vE. Uttamur Veeraghavachariyar SvAmi The Ten Main Upanishads (daSopanishads) 1. ISAvAsyopanishad 2. Kenopanishad 3. KaThopanishad 4. PraSnopanishad 5. MuNDakopanishad 6. mANDUkyopanishad 7. taittirIyopanishad 8. aitreyopanishad 9. chAndogyopanishad 10. brhadAraNyakopanishad Other Upanishads 11. SvetASvataropanishad 12. atharvaSiropanishad 13. atharvaSikopanishad 14. kaushItaki upanishad 15. Mantrikopanishad 16. subAlopanishad 17. agnirahasyam 18. Mahopanishad 19. ashTAkshara nArAyaNopanishad PurushasUktam 3 About SrI “abhinava dESika” UttamUr Tirumalai “VAtsya” VeerarAghavAchArya SvAmi (Reproduced verbatim from http://www.uttamurswami.org/wordpress/) This Web-Page is dedicated for sharing the biography, special achievements and related issues of one of the great -

PREMA VAHINI Stream of Love

PREMA VAHINI Stream of Love SATHYA SAI BABA Contents Prema Vahini 5 Dear Reader 6 Preface for the Ebook Version 7 Prema Vahini 8 1. Good character is spiritual power 8 2. Reshape character by cultivating noble qualities 8 3. Read life histories of saints and sages 9 4. Cultivate one-pointedness and equal vision 9 5. First search and correct faults within yourself 10 6. Life is a selfless loving sacrifice 10 7. Thou art That (Thath-twam-asi) 11 8. Consecrate every act as worship of the Lord 11 9. Fill every deed with service, devotion, wisdom 11 10. I and you, we, should become He 12 11. Shed attachment to worldly pleasures, develop attachment to God 12 12. Good character, virtue is wisdom 12 13. Reach God by the path of truth and discrimination 13 14. Meditate on God as truth and love 14 15. Eschew selfishness, conceit, and pride 14 16. Avoid argumentation and exhibition of scholarship 14 17. Avoid doubters and ignorant people 15 18. Develop devotion and faith 15 19. Cultivate love through two methods 16 20. See the macrocosm in the microcosm 16 21. Listen, contemplate, and sing God’s name 17 22. Seek knowledge of the Eternal Truth 17 23. Don’t neglect the study of Sanskrit and Vedic culture 18 24. Don’t mistake appearance for reality 18 25. Understand that the objective world is as unreal as the dream world 19 26. The journey of life depends on inborn desires 20 27. Direct your life to acquire your last moment’s mental tendency 20 28. -

CLAT 2020 - UG - Invite List

CLAT 2020 - UG - Invite List Candidates list below are invited for CLAT 2020 counselling process. Please login to your account and complete the counselling process before 7 Oct 2020, 6:00 PM. Name Admit Card No Aprajita C028010109 ADYA SINGH C028010463 Jai Singh Rathor C028040254 Div Kr Singh C188030178 Anand Kumar C028020900 SHAILJA BERIA C198031807 ANHAD KAUR MEHTA C142010171 Ritik raj C028070383 Ayush Singh Tomar C187020178 Shantanu C152010028 Niharika Mukherjee C034230032 Pratyay Amrit C028040343 KARTIK GILL C142010249 Aman Patidar C100010583 Varun Kumar Pathak C034160252 Krishanu Paul C019010047 Hemant Sharma C148020210 Abhiram Nitin C073040431 ISHAN THAKUR C100020046 Debditya Saha C198031256 Chiranth S C073040061 Ria Surbhi C028040133 GUNJAN MODI C073040295 SHUBHRANSHU SURAJ C028040009 ARJUN VIVEKANANDA HARIHAR C073030026 Ankit Bhardwaj C028020224 Debmalya Biswas C098030299 Vedant Bisht C197010039 KALPTARU GOEL C034070431 Ananya Chaturvedi C186010653 Palak Kumar C198031198 ARYAN NAAGAR C178010192 Shreyas Sinha C198031848 Anamika Vats C027010015 Shikhar Sharma C036010291 MONISH DIXIT C146010030 Swapnil Das C198031796 Shivansh Chandra Bagadiya C100010404 Ayush Dikshit C070010240 BARKHA SINGH C166020309 ABHISHEK JASUJA C152010108 CHHAVI C049010055 SANYAM JHA C198030020 Himanshi C058010064 Suryanshu C187060017 Radhika Singhal C173020229 HARIT GANDHI C069010002 Yashwant Kumar C028020011 Hayden D'Souza C073010055 ADITYA SARMA C132030027 Vidhi Srivastava C101010067 Aditya C049020190 Induja Sharma C042010013 KUSHAGRA VARDHAN C152010029 -

Hindu Dharma?

Balagokulam Guide Name: ___________________________________________ City, State: ___________________________________________ Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS) PREFACE We are extremely joyful to provide the balagokulam guide for all HSS karyakartas who are engaged in conducting weekly shakhas all over US. They have been putting considerable amount of their time to determine the bouddhik program and find or develop suitable bouddhik material for their respective shakhas. We hope that this guide will be a good resource for them and it will also reduce the amount of time and energy they have been investing in finding or developing bouddhik material. The balagokulam guide is a result of immeasurable efforts of many individuals. It has contents that are good enough for at least two years. It covers shloka, subhashita, amrutvachan and hundreds of articles divided in different categories such as festivals and stories. It has been reviewed and perfected by erudite individuals. However, it is possible that you may find any discrepancy. In that case, feel free to contact us and we will be happy to rectify it when the guide is published next time. Credits: Kalpita Abhyankar Santosh Prabhu Sabitha Patel Smita Gadre Shyam Gokhale Dr. Shambhu Shastri Madhumita Narayan Sampath Kumar and many other swayam-sevaks and sevikas..... Table of Contents Shloka, Subhashita, Amrutvachan, Sayings .....................................A Utsav (Festivals) .............................................................................................. B Makara Samkranti