1 Introduction – Feminism, Governmentality and 'Male' Rape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Copyright © 2021 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization, Strength, and Flaws on Characters’ Mortality Ashley Wellman Texas Christian University & Michele Bisaccia Meitl Texas Christian University & Patrick Kinkade Texas Christian University 128 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Abstract Popular culture has often referenced formulaic ways to predict a character’s fate in slasher films. The cliché rules have noted only virgins live, black characters die first, and drinking and drugs nearly guarantee your death, but to what extent do characters’ basic demographics and portrayal determine whether a character lives or dies? A content analysis of forty-eight of the most influential slasher films from the 1960s – 2010s was conducted to measure factors related to character mortality. From these films, gender, race, sexualization (measured via specific acts and total sexualization), strength, and flaws were coded for 504 non killer characters. Results indicate that the factors predicting death vary by gender. For male characters, those appearing weak in terms of physical strength or courage and those males who appeared morally flawed were more likely to die than males that were strong and morally sound. Predictors of death for female characters included strength and the presence of sexual behavior (including dress, flirtatious attitude, foreplay/sex, nudity, and total sexualization). -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Read an Excerpt

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

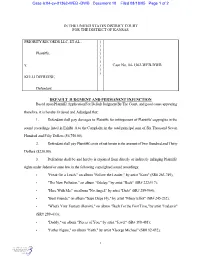

RIAA/Defreese/Proposed Default Judgment and Permanent Injunction

Case 6:04-cv-01362-WEB -DWB Document 10 Filed 08/18/05 Page 1 of 2 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS PRIORITY RECORDS LLC, ET AL., ) ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) ) v. ) Case No. 04-1362-WEB-DWB ) ) KELLI DEFREESE, Defendant. DEFAULT JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Application For Default Judgment By The Court, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Six Thousand Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars ($6,750.00). 2. Defendant shall pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Two Hundred and Thirty Dollars ($230.00). 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights under federal or state law in the following copyrighted sound recordings: C "Freak On a Leash," on album "Follow the Leader," by artist "Korn" (SR# 263-749); C "The New Pollution," on album "Odelay," by artist "Beck" (SR# 222-917); C "Here With Me," on album "No Angel," by artist "Dido" (SR# 289-904); C "Best Friends," on album "Supa Dupa Fly," by artist "Missy Elliot" (SR# 245-232); C "What's Your Fantasy (Remix)," on album "Back For the First Time," by artist "Ludacris" (SR# 289-433); C "Daddy," on album "Pieces of You," by artist "Jewel" (SR# 198-481); C "Father Figure," on album "Faith," by artist "George Michael" (SR# 92-432); 1 Case 6:04-cv-01362-WEB -DWB Document -

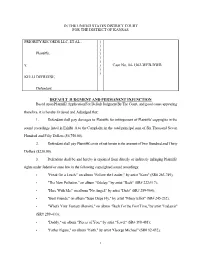

RIAA/Defreese/Proposed Default Judgment and Permanent Injunction

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF KANSAS PRIORITY RECORDS LLC, ET AL., ) ) ) Plaintiffs, ) ) ) v. ) Case No. 04-1362-WEB-DWB ) ) KELLI DEFREESE, Defendant. DEFAULT JUDGMENT AND PERMANENT INJUNCTION Based upon Plaintiffs' Application For Default Judgment By The Court, and good cause appearing therefore, it is hereby Ordered and Adjudged that: 1. Defendant shall pay damages to Plaintiffs for infringement of Plaintiffs' copyrights in the sound recordings listed in Exhibit A to the Complaint, in the total principal sum of Six Thousand Seven Hundred and Fifty Dollars ($6,750.00). 2. Defendant shall pay Plaintiffs' costs of suit herein in the amount of Two Hundred and Thirty Dollars ($230.00). 3. Defendant shall be and hereby is enjoined from directly or indirectly infringing Plaintiffs' rights under federal or state law in the following copyrighted sound recordings: C "Freak On a Leash," on album "Follow the Leader," by artist "Korn" (SR# 263-749); C "The New Pollution," on album "Odelay," by artist "Beck" (SR# 222-917); C "Here With Me," on album "No Angel," by artist "Dido" (SR# 289-904); C "Best Friends," on album "Supa Dupa Fly," by artist "Missy Elliot" (SR# 245-232); C "What's Your Fantasy (Remix)," on album "Back For the First Time," by artist "Ludacris" (SR# 289-433); C "Daddy," on album "Pieces of You," by artist "Jewel" (SR# 198-481); C "Father Figure," on album "Faith," by artist "George Michael" (SR# 92-432); 1 C "Caught Out There," on album "Kaleidoscope," by artist "Kelis" (SR# 277-087); C "I'd Rather Fuck -

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror

Screams on Screens: Paradigms of Horror Barry Keith Grant Brock University [email protected] Abstract This paper offers a broad historical overview of the ideology and cultural roots of horror films. The genre of horror has been an important part of film history from the beginning and has never fallen from public popularity. It has also been a staple category of multiple national cinemas, and benefits from a most extensive network of extra-cinematic institutions. Horror movies aim to rudely move us out of our complacency in the quotidian world, by way of negative emotions such as horror, fear, suspense, terror, and disgust. To do so, horror addresses fears that are both universally taboo and that also respond to historically and culturally specific anxieties. The ideology of horror has shifted historically according to contemporaneous cultural anxieties, including the fear of repressed animal desires, sexual difference, nuclear warfare and mass annihilation, lurking madness and violence hiding underneath the quotidian, and bodily decay. But whatever the particular fears exploited by particular horror films, they provide viewers with vicarious but controlled thrills, and thus offer a release, a catharsis, of our collective and individual fears. Author Keywords Genre; taboo; ideology; mythology. Introduction Insofar as both film and videogames are visual forms that unfold in time, there is no question that the latter take their primary inspiration from the former. In what follows, I will focus on horror films rather than games, with the aim of introducing video game scholars and gamers to the rich history of the genre in the cinema. I will touch on several issues central to horror and, I hope, will suggest some connections to videogames as well as hints for further reflection on some of their points of convergence. -

Nu-Metal As Reflexive Art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected]

Vassar College Digital Window @ Vassar Senior Capstone Projects 2016 Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art Niccolo Porcello Vassar College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone Recommended Citation Porcello, Niccolo, "Affective masculinities and suburban identities: Nu-metal as reflexive art" (2016). Senior Capstone Projects. Paper 580. This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Window @ Vassar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of Digital Window @ Vassar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! AFFECTIVE!MASCULINITES!AND!SUBURBAN!IDENTITIES:!! NU2METAL!AS!REFLEXIVE!ART! ! ! ! ! ! Niccolo&Dante&Porcello& April&25,&2016& & & & & & & Senior&Thesis& & Submitted&in&partial&fulfillment&of&the&requirements& for&the&Bachelor&of&Arts&in&Urban&Studies&& & & & & & & & _________________________________________ &&&&&&&&&Adviser,&Leonard&Nevarez& & & & & & & _________________________________________& Adviser,&Justin&Patch& Porcello 1 This thesis is dedicated to my brother, who gave me everything, and also his CD case when he left for college. Porcello 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1: Click Click Boom ............................................................................................. -

Horror Genre in National Cinemas of East Slavic Countries

Studia Filmoznawcze 35 Wroc³aw 2014 Volha Isakava University of Ottawa, Canada HORROR GENRE IN NATIONAL CINEMAS OF EAST SLAVIC COUNTRIES In this essay I would like to outline several tendencies one can observe in con- temporary horror fi lms from three former Soviet republics: Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. These observations are meant to chart the recent (2000-onwards) de- velopment of horror as a genre of mainstream cinema, and what cultural, social and political forces shape its development. Horror fi lm is of particular interest to me because it is a popular genre known for a long and interesting history in American cinema. In addition, horror is one of transnational genres that infuse Hollywood formula with particularities of national cinematic traditions (most no- table example is East Asian horror cinema, namely “J-horror,” Japanese horror). To understand the peculiarity of the newly emerged horror genre in the cinemas of East Slavic countries, I propose two venues of exploration, or two perspectives. The fi rst one could be called the global perspective: horror fi lm, as it exists today in post-Soviet space, is profoundly infl uenced by Hollywood. Domestic produc- tions compete with American fi lms at the box offi ce and strive to emulate genre structures of Hollywood to attract viewers, whose tastes are largely shaped by American fi lms. This is especially true for horror, which has almost no reference point in national cinematic traditions in question. The second vantage point is local: the local specifi city of these horror narratives, how the fi lms refl ect their own cultural condition, shaped by today’s globalized cinema market, Hollywood hegemony and local sensibilities of distinct cinematic and pop-culture traditions. -

The Final Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2017 The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016 Lauren Cupp Scripps College Recommended Citation Cupp, Lauren, "The inF al Girl Grown Up: Representations of Women in Horror Films from 1978-2016" (2017). Scripps Senior Theses. 958. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/958 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FINAL GIRL GROWN UP: REPRESENTATIONS OF WOMEN IN HORROR FILMS FROM 1978-2016 by LAUREN J. CUPP SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR TRAN PROFESSOR MACKO DECEMBER 9, 2016 Cupp 2 I was a highly sensitive kid growing up. I was terrified of any horror movie I saw in the video store, I refused to dress up as anything but a Disney princess for Halloween, and to this day I hate haunted houses. I never took an interest in horror until I took a class abroad in London about horror films, and what peaked my interest is that horror is much more than a few cheap jump scares in a ghost movie. Horror films serve as an exploration into our deepest physical and psychological fears and boundaries, not only on a personal level, but also within our culture. Of course cultures shift focus depending on the decade, and horror films in the United States in particular reflect this change, whether the monsters were ghosts, vampires, zombies, or aliens. -

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia Email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent

Science Fiction/San Francisco Issue 25 Date: July 5, 2006 Editors: Jean Martin, Chris Garcia email: [email protected] Copy Editor: David Moyce Layout: Eva Kent TOC News and Notes ...........................................Christopher J. Garcia ....................................................................................................3 Letters of Comment .....................................Jean Martin and Chris Garcia ....................................................................................4-6 Editorial .......................................................Jean Martin ................................................................................................................... 7 Ghosts and Surreal Art in Portland ...............Jean Marin ................................Photos Jean Martin ................................................8-11 Nemo Gould Sculptures ...............................Espana Sheriff ...........................Photos from www.nemomatic.com ......................12-13 Reading at Intersection for the Arts ..............Christopher J. Garcia ............................................................................................14-15 Klingon Celebration .....................................Jean Marin ................................Photos by Jean Martin .........................................16-21 BASFA Minutes ..........................................................................................................................................................................22-24 -

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught up in You .38 Special Hold on Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without

Artist Song Weird Al Yankovic My Own Eyes .38 Special Caught Up in You .38 Special Hold On Loosely 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Doors Down When You're Young 30 Seconds to Mars Attack 30 Seconds to Mars Closer to the Edge 30 Seconds to Mars The Kill 30 Seconds to Mars Kings and Queens 30 Seconds to Mars This is War 311 Amber 311 Beautiful Disaster 311 Down 4 Non Blondes What's Up? 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect The 88 Sons and Daughters a-ha Take on Me Abnormality Visions AC/DC Back in Black (Live) AC/DC Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (Live) AC/DC Fire Your Guns (Live) AC/DC For Those About to Rock (We Salute You) (Live) AC/DC Heatseeker (Live) AC/DC Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (Live) AC/DC Hells Bells (Live) AC/DC Highway to Hell (Live) AC/DC The Jack (Live) AC/DC Moneytalks (Live) AC/DC Shoot to Thrill (Live) AC/DC T.N.T. (Live) AC/DC Thunderstruck (Live) AC/DC Whole Lotta Rosie (Live) AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long (Live) Ace Frehley Outer Space Ace of Base The Sign The Acro-Brats Day Late, Dollar Short The Acro-Brats Hair Trigger Aerosmith Angel Aerosmith Back in the Saddle Aerosmith Crazy Aerosmith Cryin' Aerosmith Dream On (Live) Aerosmith Dude (Looks Like a Lady) Aerosmith Eat the Rich Aerosmith I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith Janie's Got a Gun Aerosmith Legendary Child Aerosmith Livin' On the Edge Aerosmith Love in an Elevator Aerosmith Lover Alot Aerosmith Rag Doll Aerosmith Rats in the Cellar Aerosmith Seasons of Wither Aerosmith Sweet Emotion Aerosmith Toys in the Attic Aerosmith Train Kept A Rollin' Aerosmith Walk This Way AFI Beautiful Thieves AFI End Transmission AFI Girl's Not Grey AFI The Leaving Song, Pt. -

Korn Highlights a Comprehensive List of Accomplishments While Brian "Head" Welch Was a Member of Korn

Korn Highlights A comprehensive list of accomplishments while Brian "Head" Welch was a member of Korn AWARDS Won a Grammy for Best Metal Performance – 2003 Won a Grammy for Short Form Music Video – 2000 Won a MTV Video Music Award for Best Rock Video – 2000 Won a MTV Video Music Award for Best Editing – 1999 Won a MTV Video Music Award for Best Heavy Metal / Hard Rock Video – 1999 NOMINATIONS Grammys Best Metal Performance – 2004 Hard Rock Performance – 2000 Best Metal Performance – 1997 MTV Video Music Awards Best Rock Video – 2002 Best Art Direction – 1999 Video of the Year – 1999 Best Direction – 1999 Best Special Effects – 1999 Best Cinematography – 1999 Best Breakthrough Video – 1999 Viewer’s Choice – 1999 MTV Europe Awards Best Live Act – 2002 SALES HISTORY 16 Million albums sold to date in the US 32 Million albums sold worldwide as of 2009 ALBUMS Life Is Peachy (1996) Sold more than 106,000 copies its first week Follow The Leader (1998) Sold 268,000 copies its first week Certified 5x Platinum by RIAA and sold 10 million copies worldwide Issues (1999) Sold 573,000 copies Certified 3x Platinum SALES HISTORY (continued) Untouchables (2002) Sold 434,000 copies Certified Platinum Paradigm Shift (2013) Sold 113,000 DISCOGRAPHY Korn (1995) #1 on Heatseekers #72 on The Billboard 200 Life Is Peachy (1996) #3 on The Billboard 200 Follow the Leader (1998) #1 on The Billboard 200 #1 on Top Canadian Albums Issues (1999) #1 on The Billboard 200 #2 on Top Canadian Albums #2 on Top Internet Albums Untouchables (2002) #2 on The Billboard 200 #2 on Top Internet Albums #3 on Top Canadian Albums Take a Look in the Mirror (2003) #9 on Top Internet Albums #9 on The Billboard 200 Greatest Hits Vol.