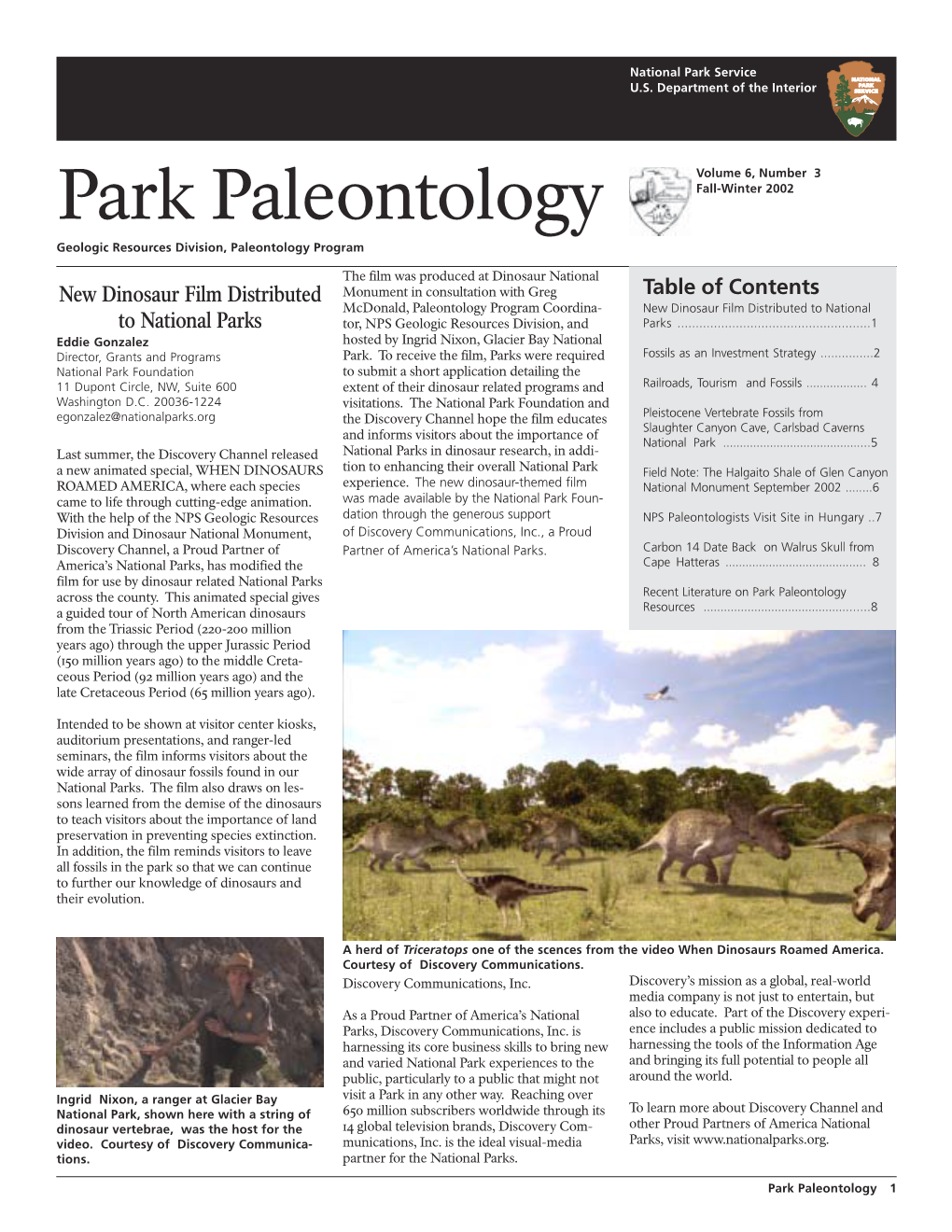

Park Paleontology Fall-Winter 2002 Geologic Resources Division, Paleontology Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rowan C. Martindale Curriculum Vitae Associate Professor (Invertebrate Paleontology) at the University of Texas at Austin

ROWAN C. MARTINDALE CURRICULUM VITAE ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR (INVERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY) AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN Department of Geological Sciences E-mail: [email protected] Jackson School of Geosciences Website: www.jsg.utexas.edu/martindale/ 2275 Speedway Stop C9000 Orchid ID: 0000-0003-2681-083X Austin, TX 78712-1722 Phone: 512-475-6439 Office: JSG 3.216A RESEARCH INTERESTS The overarching theme of my work is the connection between Earth and life through time, more precisely, understanding ancient (Mesozoic and Cenozoic) ocean ecosystems and the evolutionary and environmental events that shaped them. My research is interdisciplinary, (paleontology, sedimentology, biology, geochemistry, and oceanography) and focuses on: extinctions and carbon cycle perturbation events (e.g., Oceanic Anoxic Events, acidification events); marine (paleo)ecology and reef systems; the evolution of reef builders (e.g., coral photosymbiosis); and exceptionally preserved fossil deposits (Lagerstätten). ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Associate Professor, University of Texas at Austin September 2020 to Present Assistant Professor, University of Texas at Austin August 2014 to August 2020 Postdoctoral Researcher, Harvard University August 2012 to July 2014 Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology; Mentor: Dr. Andrew H. Knoll. EDUCATION Doctorate, University of Southern California 2007 to 2012 Dissertation: “Paleoecology of Upper Triassic reef ecosystems and their demise at the Triassic-Jurassic extinction, a potential ocean acidification event”. Advisor: Dr. David J. Bottjer, degree conferred August 7th, 2012. Bachelor of Science Honors Degree, Queen’s University 2003 to 2007 Geology major with a general concentration in Biology (Geological Sciences Medal Winner). AWARDS AND RECOGNITION Awards During Tenure at UT Austin • 2019 National Science Foundation CAREER Award: Awarded to candidates who are judged to have the potential to serve as academic role models in research and education. -

Thomas Jefferson Meg Tooth

The ECPHORA The Newsletter of the Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club Volume 30 Number 3 September 2015 Thomas Jefferson Meg Tooth Features Thomas Jefferson Meg The catalogue number Review; Walking is: ANSP 959 Whales Inside The tooth came from Ricehope Estate, Snaggletooth Shark Cooper River, Exhibit South Carolina. Tiktaalik Clavatulidae In 1806, it was Juvenile Bald Eagle originally collected or Sculpting Whale Shark owned by Dr. William Moroccan Fossils Reid. Prints in the Sahara Volunteer Outing to Miocene-Pliocene National Geographic coastal plain sediments. Dolphins in the Chesapeake Sloth Tooth Found SharkFest Shark Iconography in Pre-Columbian Panama Hippo Skulls CT- Scanned Squalus sp. Teeth Sperm Whale Teeth On a recent trip to the Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University (Philadelphia), Collections Manager Ned Gilmore gave John Nance and me a behind -the-scenes highlights tour. Among the fossils that belonged to Thomas☼ Jefferson (left; American Founding Father, principal author of the Declaration of Independence, and third President of the United States) was this Carcharocles megalodon tooth. Jefferson’s interests and knowledge were encyclopedic; a delight to know that they included paleontology. Hand by J. Nance. Photo by S. Godfrey. Jefferson portrait from: http://www.biography.com/people/thomas-jefferson-9353715 ☼ CALVERT MARINE MUSEUM www.calvertmarinemuseum.com 2 The Ecphora September 2015 Book Review: The Walking 41 million years ago and has worldwide distribution. It was fully aquatic, although it did have residual Whales hind limbs. In later chapters, Professor Thewissen George F. Klein discusses limb development and various genetic factors that make whales, whales. This is a The full title of this book is The Walking complicated topic, but I found these chapters very Whales — From Land to Water in Eight Million clear and readable. -

A Genus-Level Phylogenetic Analysis of Antilocapridae And

A GENUS-LEVEL PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF ANTILOCAPRIDAE AND IMPLICATIONS FOR THE EVOLUTION OF HEADGEAR MORPHOLOGY AND PALEOECOLOGY by HOLLEY MAY FLORA A THESIS Presented to the Department of EArth Sciences And the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partiAl fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MAster of Science September 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Holley MAy Flora Title: A Genus-level Phylogenetic Analysis of AntilocApridae and ImplicAtions for the Evolution of HeAdgeAr Morphology and PAleoecology This Thesis has been accepted and approved in partiAl fulfillment of the requirements for the MAster of Science degree in the Department of EArth Sciences by: EdwArd Byrd DAvis Advisor SAmAntha S. B. Hopkins Core Member Matthew Polizzotto Core Member Stephen Frost Institutional RepresentAtive And JAnet Woodruff-Borden DeAn of the Graduate School Original Approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School Degree awArded September 2019. ii ã 2019 Holley MAy Flora This work is licensed under a CreAtive Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (United States) License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Holley MAy Flora MAster of Science Department of EArth Sciences September 2019 Title: A Genus-level Phylogenetic Analysis of AntilocApridae and ImplicAtions for the Evolution of HeAdgeAr Morphology and PAleoecology The shapes of Artiodactyl heAdgeAr plAy key roles in interactions with their environment and eAch other. Consequently, heAdgeAr morphology cAn be used to predict behavior. For eXAmple, lArger, recurved horns are typicAl of gregarious, lArge-bodied AnimAls fighting for mAtes. SmAller spike-like horns are more characteristic of small- bodied, paired mAtes from closed environments. Here, I report a genus-level clAdistic Analysis of the extinct family, AntilocApridae, testing prior hypotheses of evolutionary history And heAdgeAr evolution. -

Some Philosophical Questions About Paleontology and Their Practica1 Consequences

ACTA GEOLOGICA HISPANICA. Concept and method in Paleontology. 16 (1981) nos 1-2, pags. 7-23 Some philosophical questions about paleontology and their practica1 consequences by Miquel DE RENZI Depto. de Geología, Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Valencia. Burjassot (Valencia). This papcr attempts to objectively discuss the actual state ofpaleontology. The En aquest treball s'ha intentat fer un balanc d'alguns aspectes de I'estat de la progress of this science stood still somewhat during the latter part of the last paleontologia. La historia de la paleontologia mostra un estancarnent a les century which caused it to develop apart from the biological sciences. an area to darreries del segle passac aquest estancament va Fer que la nostra ciencia s'anes which it is naturally tied. As aconsequence, this bruought a long-term stagnation, allunyant cada cop mes de I'area de les ciencies bii~logiques,amb les qualsestava because biology, dunng this century, has made great progress and paleontology lligada naturalment AixO va portar, com a conseqüencia, un important has not During the last 20 years paleontology as a science hasrecuperatedsome endarreriment, car la biologia, durant aquest segle, ha donat un gran pas of this loss, but we as scientists need to be careful in various aspects of its endavant, mentre que aquest no ha estat el cas de lapaleontologia Al nostre pais development -i possiblement a molts d'altres- la paleontologia es, fonamentalment, un estn per datar estrats. Tanmateix, un mal estri, car la datació es basadaen les especies fossils i la seva determinació es fonamenta en el ccncepte d'especie biolbgica; els fossils pero en moltes ocasions, són utilitzats mes aviat com si fossin segells o monedes. -

SVP's Letter to Editors of Journals and Publishers on Burmese Amber And

Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 7918 Jones Branch Drive, Suite 300 McLean, VA 22102 USA Phone: (301) 634-7024 Email: [email protected] Web: www.vertpaleo.org FEIN: 06-0906643 April 21, 2020 Subject: Fossils from conflict zones and reproducibility of fossil-based scientific data Dear Editors, We are writing you today to promote the awareness of a couple of troubling matters in our scientific discipline, paleontology, because we value your professional academic publication as an important ‘gatekeeper’ to set high ethical standards in our scientific field. We represent the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP: http://vertpaleo.org/), a non-profit international scientific organization with over 2,000 researchers, educators, students, and enthusiasts, to advance the science of vertebrate palaeontology and to support and encourage the discovery, preservation, and protection of vertebrate fossils, fossil sites, and their geological and paleontological contexts. The first troubling matter concerns situations surrounding fossils in and from conflict zones. One particularly alarming example is with the so-called ‘Burmese amber’ that contains exquisitely well-preserved fossils trapped in 100-million-year-old (Cretaceous) tree sap from Myanmar. They include insects and plants, as well as various vertebrates such as lizards, snakes, birds, and dinosaurs, which have provided a wealth of biological information about the ‘dinosaur-era’ terrestrial ecosystem. Yet, the scientific value of these specimens comes at a cost (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/science/amber-myanmar-paleontologists.html). Where Burmese amber is mined in hazardous conditions, smuggled out of the country, and sold as gemstones, the most disheartening issue is that the recent surge of exciting scientific discoveries, particularly involving vertebrate fossils, has in part fueled the commercial trading of amber. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

ISSUE VIII JANUARY 2007 NARG Newsletter North America Research Group Northwest Fossil Fest Recap Last August NARG held it's first annual Northwest Fossil Fest held at INSIDE THIS ISSUE the Rice Museum in Hillsboro Oregon. The goal of the Fest was to NW Fossil Fest Recap 1 promote, educate, showcase fossils Radiocarbon Dating Fund 3 from the Pacific NW, and to have John Day Fossil Beds fun, all of which was accomplished. National Monument 3 Taxonomy Report #6 5 The tagline for the Fest is “Inspire, Inquire, Interact” and nothing What is “Fossil Search and Rescue? inspires more than displaying some of the amazing fossils specimens that Oregon Fossils have been found in the Pacific NW. Plants of the Jurassic Period 7 Tami Smith making a batch of Trilobite Cookie Many guests where surprised at the Trilobite Morphology 8 wide range of life forms that once lived where we do today. Inquiry minds want to know and we had a top-notch line up of guest speakers such as Dr. Dr. Ellen Morris Bishop, Dr. Jeffrey A. Myers, and Dr. William. N. Orr. This was a great opportunity for guest not only to learn more about the paleontology and geology of Oregon but also to meet 3 of the leading professionals in these fields. More Trilobite Cookie making There were many ways to interact, from the fossil preparation area where demonstrations took place on tools and techniques used to prepare fossils, to fossil identification, and of course all the kids activities that NARG setup. The Screen for Shark Teeth was probably the biggest hits and over 1000 Bone Valley shark teeth where given away. -

Article the Skull of Teleosaurus Cadomensis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29(1):88–102, March 2009 # 2009 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology ARTICLE THE SKULL OF TELEOSAURUS CADOMENSIS (CROCODYLOMORPHA; THALATTOSUCHIA), AND PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF THALATTOSUCHIA STE´ PHANE JOUVE Muse´um National d’Histoire Naturelle de Paris, De´partement Histoire de la Terre, CNRS UMR 5143, 8 rue Buffon, 75005 Paris, France, [email protected] ABSTRACT—Several Teleosaurus skulls were described during the nineteenth century. Unfortunately, all skulls from this genus were destroyed during World War II. The only available skull is currently preserved in the MNHN. Thanks to a new preparation, new anatomical features can be seen, such as the morphology of the nasal cavity, the external otic recess, and the distribution of the foramina for the cranial nerves. A phylogenetic analysis is presented, including 14 thalattosu- chian taxa. This analysis has generated four equally most parsimonious trees, where the thalattosuchians are closely related to the pholidosaurids and dyrosaurids, forming a longirostrine taxa. These relationships have been often consid- ered to be based on homoplasies, related to the longirostrine morphology. This is also suggested herein, as the deletion of the longirostrine dependant characters or of the most longirostrine thalattosuchians in the analysis provide a consensus tree where thalattosuchians are basal crocodyliforms, a result more generally accepted. As the deletion of the most longirostrine thalattosuchians precludes the longirostrine problem in the phylogenetic analysis of Crocodyliformes, this deletion seems to be the less unsatisfactory solution to assess the crocodyliform relationships. -

Rocky Start of Dinosaur National Monument (USA), the World's First Dinosaur Geoconservation Site

Original Article Rocky Start of Dinosaur National Monument (USA), the World's First Dinosaur Geoconservation Site Kenneth Carpenter Prehistoric Museum, Utah State University Eastern Price, Utah 80504 USA Abstract The quarry museum at Dinosaur National Monument, which straddles the border between the American states of Colorado and Utah, is the classic geoconservation site where visitors can see real dinosaur bones embedded in rock and protected from the weather by a concrete and glass structure. The site was found by the Carnegie Museum in August 1909 and became a geotourist site within days of its discovery. Within a decade, visitors from as far as New Zealand traveled the rough, deeply rutted dirt roads to see dinosaur bones in the ground for themselves. Fearing that the site would be taken over by others, the Carnegie Museum attempted twice to take the legal possession of the land. The second attempt had consequences far beyond what the Museum intended when the federal government declared the site as Dinosaur National Monument in 1915, thus taking ultimate control from the Carnegie Museum. Historical records and other archival data (correspondence, diaries, reports, newspapers, hand drawn maps, etc.) are used to show that the unfolding of events was anything but smooth. It was marked by misunderstanding, conflicting Corresponding Author: goals, impatience, covetousness, miscommunication, unrealistic expectation, intrigue, and some Kenneth Carpenter paranoia, which came together in unexpected ways for both the Carnegie Museum and the federal Utah State University Eastern Price, government. Utah 80504 USA Email: [email protected] Keywords: Carnegie Museum, Dinosaur National Monument, U.S. National Park Service. -

The Geology and Mineral Resources of the John Day Region by Arthur J

VOLUME I NUMBER 3 MARCH, 1914 THE MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON Published Monthly By The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology Small'? Ranch and Field's Mountain on John Day River. CONTENTS. The Geology and Mineral Resources of the John Day Region by Arthur J. Collier Entered aa second clam matter at Corvallis, Ore. on Feb 10, 1914, according to the Act of Aug. 24, 1912. OREGON BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY COMMISSION Omci or THE COMMISSION tit YEON BUILDING, PORTLAND, OREGON Omci or THE DlHECTOB CORVALLI8. OREGON OSWALD WEST, Governor STAFF COMMISSION HENBT M. PARES, Director ARTHUR M. SWABTLET, Mining Eng'r H. N. LAWBIE, Portland IRA A. WILLIAMS, Ceramist W. C. Fraxows, VVhitney SIDNEY W. FRENCH, Metallurgist I. ¥ RSDDT, Medford C. T. PBALL, Ontario FIELD PARTY CHIEFS T. 8. MANN, Portland P. L. CAMPBELL, Eugene A. N. WlNCHBLL W. J. KERB, Corvallis U. 8. GBAHT A J. COLLIEB SOLON SHEDD GSOBOB D. LOUDBBBACE VOLUME I NUMBER 3 MARCH, 1914 THE MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON A Periodical Devoted to the Development of all her Minerals PUBLISHED MONTHLY AT CORVALLIS BY THE OREGON BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY H. M. PARKS, Director *THE GEOLOGY AND MINERAL RESOURCES OF THE JOHN DAY REGION. By Arthur J. Collier. The John Day river basin in the north central part of Oregon has been for many years a favorite place for geologic exploration, on account of the occurrence there of vertebrate fossils. In recent years, however, attention has been further directed to this region from time to time by reports of the discovery of coal, oil, gas and other mineral resources. -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

John Day Fossil Beds NM: Geology and Paleoenvironments of the Clarno Unit

John Day Fossil Beds NM: Geology and Paleoenvironments of the Clarno Unit JOHN DAY FOSSIL BEDS Geology and Paleoenvironments of the Clarno Unit John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon GEOLOGY AND PALEOENVIRONMENTS OF THE CLARNO UNIT John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon By Erick A. Bestland, PhD Erick Bestland and Associates, 1010 Monroe St., Eugene, OR 97402 Gregory J. Retallack, PhD Department of Geological Sciences University of Oregon Eugene, OR 7403-1272 June 28, 1994 Final Report NPS Contract CX-9000-1-10009 TABLE OF CONTENTS joda/bestland-retallack1/index.htm Last Updated: 21-Aug-2007 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/joda/bestland-retallack1/index.htm[4/18/2014 12:20:25 PM] John Day Fossil Beds NM: Geology and Paleoenvironments of the Clarno Unit (Table of Contents) JOHN DAY FOSSIL BEDS Geology and Paleoenvironments of the Clarno Unit John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, Oregon TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER ABSTRACT ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION AND REGIONAL GEOLOGY INTRODUCTION PREVIOUS WORK AND REGIONAL GEOLOGY Basement rocks Clarno Formation John Day Formation CHAPTER II: GEOLOGIC FRAMEWORK INTRODUCTION Stratigraphic nomenclature Radiometric age determinations CLARNO FORMATION LITHOSTRATIGRAPHIC UNITS Lower Clarno Formation units Main section JOHN DAY FORMATION LITHOSTRATIGRAPHIC UNITS Lower Big Basin Member Middle and upper Big Basin Member Turtle Cove Member GEOCHEMISTRY OF LAVA FLOW AND TUFF UNITS Basaltic lava flows Geochemistry of andesitic units Geochemistry of tuffs STRUCTURE OF CLARNO