Newsletter of Mar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of the Liverworts and Hornworts of the Interior Highlands of North America in Arkansas, Illinois, Missouri and Oklahoma

Checklist of the Liverworts and Hornworts of the Interior Highlands of North America In Arkansas, Illinois, Missouri and Oklahoma Stephen L. Timme T. M. Sperry Herbarium ‐ Biology Pittsburg State University Pittsburg, Kansas 66762 and 3 Bowness Lane Bella Vista, AR 72714 [email protected] Paul Redfearn, Jr. 5238 Downey Ave. Independence, MO 64055 Introduction Since the last publication of a checklist of liverworts and hornworts of the Interior Highlands (1997)), many new county and state records have been reported. To make the checklist useful, it was necessary to update it since its last posting. The map of the Interior Highlands of North America that appears in Redfearn (1983) does not include the very southeast corner of Kansas. However, the Springfield Plateau encompasses some 88 square kilometers of this corner of the state and includes limestone and some sandstone and shale outcrops. The vegetation is typical Ozarkian flora, dominated by oak and hickory. This checklist includes liverworts and hornworts collected from Cherokee County, Kansas. Most of what is known for the area is the result of collections by R. McGregor published in 1955. The majority of his collections are deposited in the herbarium at the New York Botanical Garden (NY). This checklist only includes the region defined as the Interior Highlands of North America. This includes the Springfield Plateau, Salem Plateau, St. Francois Mountains, Boston Mountains, Arkansas Valley, Ouachita Mountains and Ozark Hills. It encompasses much of southern Missouri south of the Missouri River, southwest Illinois; most of Arkansas except the Mississippi Lowlands and the Coastal Plain, the extreme southeastern corner of Kansas, and eastern Oklahoma (Fig. -

July 2007 Volume 38, No.2

July 2007 Volume 38, No.2 THE OSPREY __________________________________ NATURE JOURNAL OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR Publication Mail Registration # 8302 ISSN 0710-4847 THE NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR P.O. Box 1013, St. John’s, NL A1C 5M3 Editorial Policy: All members are encouraged to contribute articles and materials in accordance with the society’s mandate for publication in “The Osprey” Articles should be submitted via 3.5” High-density IBM-formatted fl oppy disks or Compact Disk. Computer users should prepare articles in Word Perfect or MS Word or text fi le. Font, margins, and spacing can be adjusted by the editor. The editor reserves the right to re-format any materials received. Please note that all material will be reviewed by the editorial staff and only those deemed appropriate will be published. Illustrations and photos are welcome, and should be provided in a format compatible with photocopying in black and white. Submissions for publication can be mailed to: P.O. Box 1013 St. John’s, NL A1C 5M3 or emailed to the editor at: [email protected] “The Osprey does not print advertising or solicitations without the expressed consent of the executive. Views expressed in “Letters to the Editor” are not necessarily the views of the editor or the executive of the Society. Natural History Society Executive (Mar. 2007 - 2008). Website: www.nhs.nf.ca e-mail: [email protected] HOME WORK FAX President - Rita Anderson [email protected] 895-2564 737-8771 737-2430 Vice President - John Jacobs [email protected] 738-3147 737-8194 737-3119 Secretary- Don Steele [email protected] 754-0455 737-7520 737-3018 Treasurer - Jackie Feltham [email protected] 895-0477 895-7776 Osprey Editor - Elizabeth Zedel [email protected] 754-3321 Associate Editor - John Jacobs [email protected] 738-3147 Humber Rep. -

High Levels of Endemism Among Galapagos Basidiolichens

Fungal Diversity (2017) 85:45–73 DOI 10.1007/s13225-017-0380-6 High levels of endemism among Galapagos basidiolichens 1,2 3,4 5 Manuela Dal Forno • Frank Bungartz • Alba Ya´nez-Ayabaca • 6,7 2 Robert Lu¨cking • James D. Lawrey Received: 29 December 2016 / Accepted: 7 April 2017 / Published online: 20 April 2017 Ó School of Science 2017 Abstract This study is a re-assessment of basidiolichen namely Cora galapagoensis, Cyphellostereum uno- diversity in the Galapagos Islands. We present a molecular quinoum, Dictyonema barbatum, D. darwinianum, D. phylogenetic analysis, based on 92 specimens from Gala- ramificans, and D. subobscuratum; and four species have pagos, using two nuclear ribosomal DNA markers (ITS and already been described previously, namely Acantholichen nuLSU). We also re-examined the morphology and anat- galapagoensis, Cora santacruzensis, Dictyonema pectina- omy of all sequenced material. The molecular results tum, and D. galapagoense, here recombined as Cyphel- confirm our previous assessment that all Galapagos lostereum galapagoense. Our analysis is set on a very basidiolichens belong to the Dictyonema clade, which in broad phylogenetic framework, which includes a large Galapagos is represented by four genera: Acantholichen, number of specimens (N = 826) mainly from Central and Cora, Cyphellostereum, and Dictyonema. Most species South America, and therefore strongly suggests an unusu- previously reported from Galapagos in these genera were at ally high level of endemism previously not recognized. the time believed to represent widely distributed taxa. This This analysis also shows that the closest relatives of half of conclusion, however, has changed with the inclusion of the basidiolichens now found in Galapagos are from molecular data. -

Cyanobacteria in Terrestrial Symbiotic Systems

Cyanobacteria in Terrestrial Symbiotic Systems Jouko Rikkinen Abstract Filamentous cyanobacteria are important primary producers and N2 fixers in many terrestrial environments. As reduced nitrogen is often limiting, some thalloid liverworts (Marchantiophyta), hornworts (Anthocerophyta), the water fern Azolla (Salviniales), cycads (Cycadophyta), and the angiosperm Gunnera (Gunnerales) have evolved the ability to establish stable and structurally well-defined symbioses with N2-fixing cyanobacteria. Also a wide diversity of lichen-forming fungi have cyanobacteria as photosynthetic symbionts or as N2-fixing symbionts. Cyanolichen symbioses have evolved independently in different fungal lineages, and evolution has often resulted in convergent morphologies in distantly related groups. DNA techniques have provided a wealth of new information on the diversity of symbiotic cyanobacteria and their hosts. The fact that many plants and fungi engage in many different symbioses simultaneously underlines the probable significance of diffuse evolutionary relationships between different symbiotic systems, including cyanobacterial and mycorrhizal associations. This review introduces the reader to recent research on symbiotic cyanobacteria in terrestrial ecosystems and shortly describes the astonishing range of diversity in these ecologically important associations. Introduction Mutually beneficial symbiotic interactions are an inherent feature of most ecological communities. Nitrogen is essential for growth of land plants, but the availability of reduced nitrogen in the soil is often limiting. Diazotrophic bacteria are able to convert atmospheric dinitrogen (N2) to ammonia (NH3) that can be utilized by plants, and consequently, numerous land plants form an association with N2-fixing bacteria. These interactions include the morphologically and physiologically highly coevolved symbioses between legumes and rhizobia, between actinorhizal plants and Frankia, and a plethora of more casual associations between plants and prokaryotic diazotrophs (Bothe et al. -

Volume 4, Chapter 1-7: Aquatic and Wet Marchantiophyta, Class

Glime, J. M. 2021. Aquatic and Wet Marchantiophyta, Class Jungermanniopsida, Orders Porellales: Jubulineae, part 1. Chapt. 1-7. In: 1-7-1 Glime, J. M. (ed.). Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 4. Habitat and Role. Ebook sponsored by Michigan Technological University and the International Association of Bryologists. Last updated 22 May 2021 and available at <http://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/bryophyte-ecology/>. CHAPTER 1-7 AQUATIC AND WET MARCHANTIOPHYTA, CLASS JUNGERMANNIOPSIDA, ORDER PORELLALES: JUBULINEAE, PART 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Porellales – Suborder Jubulineae ........................................................................................................................ 1-7-2 Frullaniaceae ................................................................................................................................................ 1-7-2 Frullania asagrayana ........................................................................................................................... 1-7-2 Frullania riparia ................................................................................................................................... 1-7-4 Frullania tamarisci ............................................................................................................................... 1-7-5 Frullania teneriffae ............................................................................................................................... 1-7-7 Jubulaceae ................................................................................................................................................... -

Boreal Felt Lichen (Erioderma Pedicellatum), Boreal Population

Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series Adopted under Section 69 of SARA Management Plan for the Boreal Felt Lichen – Boreal Population (Erioderma pedicellatum) in Canada Boreal Felt Lichen – Boreal Population 2010 About the Species at Risk Act Management Plan Series What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)? SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003, and one of its purposes is “to manage species of special concern to prevent them from becoming endangered or threatened.” What is a species of special concern? Under SARA, a species of special concern is a wildlife species that could become threatened or endangered because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats. Species of special concern are included in the SARA List of Wildlife Species at Risk. What is a management plan? Under SARA, a management plan is an action-oriented planning document that identifies the conservation activities and land use measures needed to ensure, at a minimum, that a species of special concern does not become threatened or endangered. For many species, the ultimate aim of the management plan will be to alleviate human threats and remove the species from the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. The plan sets goals and objectives, identifies threats, and indicates the main areas of activities to be undertaken to address those threats. Management plan development is mandated under sections 65-72 of SARA (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/approach/act/default_e.cfm). -

Curriculum Vitae Blanka Aguero (Shaw, Buryová)

Curriculum Vitae Blanka Aguero (Shaw, Buryová) Address: Duke University Herbarium Phone: 919 660‐7308 Department of Biology, Box 90338 Fax: 919 660‐7293 Duke University email: [email protected] Durham, NC 27708‐0338 https://scholar.google.com/citations?hl=en&user=W7BXsG4AAAAJ http://expeditions.fieldmuseum.org/test/blanka‐shaw‐phd Degrees Ph.D. Department of Botany, Charles University, Prague, thesis: Morphological and genetic variation in selected species of the genus Philonotis (Bartramiaceae, Bryopsida), 2004 RNDr. Department of Botany, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic, 2001 MSc. Department of Botany, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic, 1996 Professional experience 10/2004‐present: Herbarium Data Manager, Department of Biology, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA 1998‐2004: Junior research fellow, graduate student, Department of Taxonomy and Biosystematics, Institute of Botany, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Průhonice (bryology) 1996‐1999: Graduate student, Charles University in Prague, Department of Botany (teaching assistant, course on Systematics and evolution of non‐vascular plants and fungi) Research interests Systematics of bryophytes; Ecological bioinformatics; Bryophyte ecology, diversity and dynamics in montane and alpine ecosystems, wetlands, and hyperoceanic environments; Natural history collections management. Field experience: temperate and boreal regions of Europe, North America and Asia; Australia; South Africa; southern South America; Fiji & New Caledonia. Research projects financed by grant agencies in the United States National Science Foundation Award 1146168 ‐ ARTS: Collaborative Research: A model systematic treatment of a hyper‐diverse lineage descended from early land plants (Frullania, Frullaniaceae, Marchantiophyta), principal investigator, 2012‐2015 National Science Foundation Award 0918998 ‐ Systematics and Evolution of the "Pacific Rim Clade" of Sphagnum section Subsecunda, Co‐principal Investigator, PI: A.J. -

A New Frullania Species from New Caledonia

Bry. Div. Evo. 40 (2): 104–112 ISSN 2381-9677 (print edition) DIVERSITY & http://www.mapress.com/j/bde BRYOPHYTEEVOLUTION Copyright © 2018 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2381-9685 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/bde.40.2.8 Unveiling the enigmatic and ambiguous: A new Frullania species from New Caledonia JUAN LARRAÍN1A*, MATT VON KONRAT2A*, LAN-HUONG NGUYEN2, BEnjAmin E. CARTER3, BLAnkA AGUERO4, MEREIA TABUA5 & LOUis ThOUVENOT6 1 Instituto de Biología, Facultad de Ciencias, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso, Campus Curauma, Valparaíso, Chile 2 Gantz Family Collections Center, Science & Education, Field Museum, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, IL 60605-2496, U.S.A. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, San Jose State University, One Washington Square, San Jose, CA 95192, U.S.A. 4 Department of Biology, Duke University, 139 Biological Sciences Building, Box 90338, Durham, North Carolina 27708, U.S.A. 5 The Institute of Applied Sciences, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji 6 11 rue Saint Léon, 66000 Perpignan, France * Corresponding authors Email address: [email protected] A These authors contributed equally to this work Abstract Frullania is a large and taxonomically complex genus with over 300 accepted species. A new liverwort species, Frullania thouvenotiana sp. nov. from New Caledonia, is described and illustrated. The new species, and its placement in Frulla- nia subg. Microfrullania, is based on morphology with support from previously published sequence data. Diagnostic charac- ters associated with the leaf, especially the leaf margin, distinguishes it from all other species of Frullania, including similar species with a distribution comprising Fiji and New Zealand. -

Juriado Et Al. 2018

Relationships between mycobiont identity, photobiont specificity and ecological preferences in the lichen genus Peltigera (Ascomycota) in Estonia (northeastern Europe) Inga Juriadoa, ∗, Ulla Kaasalainenb, Maarit Jylhac, Jouko Rikkinenb, c a Institute of Ecology and Earth Sciences, University of Tartu, Lai 38/40, Tartu, 51005, Estonia b Finnish Museum of Natural History, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 7, 00014, Helsinki, Finland c Organismal and Evolutionary Biology Research Programme, Faculty of Biological and Environmental Sciences, University of Helsinki, P.O. Box 65, 00014, Helsinki, Finland A B S T R A C T We studied the genotype diversity of cyanobacterial symbionts in the predominately terricolous cyanolichen genus Peltigera (Peltigerales, Lecanoromycetes) in Estonia. Our sampling comprised 252 lichen specimens collected in grasslands and forests from different parts of the country, which represented all common Peltigera taxa in the region. The cyanobacteria were grouped according to their tRNALeu (UAA) intron sequences, and mycobiont identities were confirmed using fungal ITS sequences. The studied Peltigera species associated with 34 different “Peltigera-type” Nostoc trnL genotypes. Some Peltigera species associated with one or a few trnL genotypes while others associated with a much wider range of genotypes. Mycobiont identity was the primary factor that determined the presence of the specific Nostoc genotype within the studied Peltigera thalli. However, the species-specific patterns of cyanobiont selectivity did not always reflect phylogenetic relationships among the studied fungal species but correlated instead with habitat preferences. Several taxa from different sections of the genus Peltigera were associated with the same Nostoc genotype or with genotypes in the same habitat, indicating the presence of functional guild structure in the photobiont community. -

Occurrence Networks Among Spatially Close Bacterial Microbiota of Bark, Mosses and Lichens

Molecular Ecology (2017) doi: 10.1111/mec.14070 Differential sharing and distinct co-occurrence networks among spatially close bacterial microbiota of bark, mosses and lichens INES ALINE ASCHENBRENNER,* TOMISLAV CERNAVA,*† ARMIN ERLACHER,* GABRIELE BERG* and MARTIN GRUBE‡ *Institute of Environmental Biotechnology, Graz University of Technology, Petersgasse 12, 8010 Graz, Austria, †ACIB GmbH, Petersgasse 14, 8010 Graz, Austria, ‡Institute of Plant Sciences, University of Graz, Holteigasse 6, 8010 Graz, Austria Abstract Knowledge of bacterial community host-specificity has increased greatly in recent years. However, the intermicrobiome relationships of unrelated but spatially close organisms remain little understood. Trunks of trees covered by epiphytes represent complex habitats with a mosaic of ecological niches. In this context, we investigated the structure, diversity and interactions of microbiota associated with lichens, mosses and the bare tree bark. Comparative analysis revealed significant differences in the habitat-associated community structures. Corresponding co-occurrence analysis indi- cated that the lichen microbial network is less complex and less densely intercon- nected than the moss- and bark-associated networks. Several potential generalists and specialists were identified for the selected habitats. Generalists belonged mainly to Proteobacteria, with Sphingomonas as the most abundant genus. The generalists com- prise microorganisms with generally beneficial features, such as nitrogen fixation or other supporting functions, according to a metagenomic analysis. We argue that benefi- cial strains shared among hosts contribute to ecological stability of the host bio- coenoses. Keywords: amplicon sequencing, co-occurrence patterns, host microbe associations, metagenome, microbial ecology Received 21 March 2016; revision received 4 January 2017; accepted 6 February 2017 3.04 trillion trees (Crowther et al. -

Checklist of Fossil Liverworts Suitable for Calibrating Phylogenetic Reconstructions

Bry. Div. Evo. 043 (1): 014–071 ISSN 2381-9677 (print edition) DIVERSITY & https://www.mapress.com/j/bde BRYOPHYTEEVOLUTION Copyright © 2021 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 2381-9685 (online edition) https://doi.org/10.11646/bde.43.1.6 Checklist of fossil liverworts suitable for calibrating phylogenetic reconstructions KATHRin FELDBERG1,*, S. ROBBERT GRADSTEin2, CARSTEN GRÖHN3, JOCHEN HEinRicHS4,†, MATT VON KONRAT5, YURiy S. MAMONTOV6, MATT A. M. REnnER7, MADITA ROTH1, ALFOns SCHÄFER-VERWimp8, PHIANGPHAK SUkkHARAK9 & ALEXANDER R. SCHmiDT1 1Department of Geobiology, University of Göttingen, Goldschmidtstraße 3, 37077 Göttingen, Germany; �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9431-7193 �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5426-4667 2Department of Systematics, Biodiversity and Evolution of Plants, Albrecht von Haller Institute for Plant Sciences, University of Göttingen, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, Institute de Systematique, Évolution, Biodiversité (UMR 7205), 75005 Paris, France; �[email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3849-6457 3Amber Study Group, c/o Geological-Palaeontological Institute and Museum (CeNak) of the University of Hamburg, Bundesstraße 55, 20146 Hamburg, Germany; �[email protected] 4Department of Biology I, Systematic Botany and Mycology, Geobio-Center, University of Munich (LMU), Menzinger Straße 67, 80638 Munich, Germany 5Gantz Family Collections Center, Science & Education, Field Museum, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, -

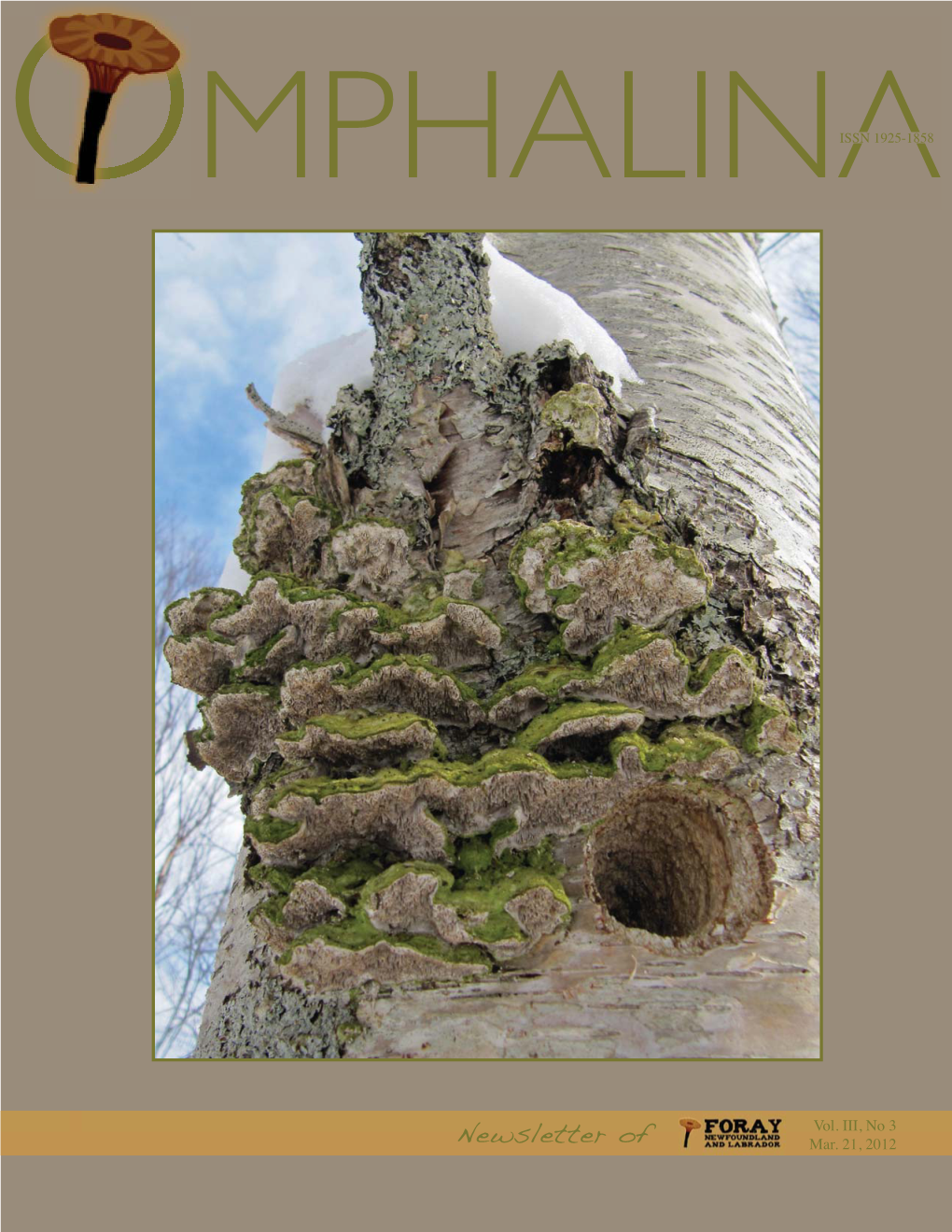

THE FORAY ISSUE ISSN 1925-1858 2019Newsletter of August 2019 • Vol X, No

OMPHALINA THE FORAY ISSUE ISSN 1925-1858 2019Newsletter of August 2019 • Vol X, No. 2 OMPHALINA, newsletter of Foray Newfoundland & Labrador, has no fi xed schedule of publication, and no promise to appear again. Its primary purpose is to serve as a conduit of information to registrants of the upcom- ing foray and secondarily as a communications tool with members. Issues of Omphalina are archived in: Board Directors C s ta s Library and Archives Canada’s Electronic Collection http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/300/omphalina/index. President Mycological html, and Michael Burzynski Dave Malloch Centre for Newfoundland Studies, Queen Elizabeth II Treasurer NB MUSEUM Library (printed copy also archived) Geoff Th urlow Auditor http://collections.mun.ca/cdm/search/collection/ompha- Secretary Gordon Janes lina/ Robert McIsaac BONNELL COLE JANES Legal Counsel Th e content is neither discussed nor approved by the Directors Board of Directors. Th erefore, opinions expressed do Bill Bryden Andrew May not represent the views of the Board, the Corporation, Shawn Dawson BROTHERS & BURDEN the partners, the sponsors, or the members. Opinions Rachelle Dove Webmaster are solely those of the authors and uncredited opinions Chris Deduke Jim Cornish solely those of the Editor. Jamie Graham Anne Marceau Past President Please address comments, complaints, and contributions Helen Spencer Andrus Voitk to the Editor, Sara Jenkins at [email protected] Foray Newfoundland and Labrador is an amateur, volunteer-run, community, not-for-profit organization with a mission to organize enjoyable Accepting C tr i s and informative amateur mushroom forays in We eagerly invite contributions to Omphalina, dealing with any aspect even remotely related to NL Newfoundland and Labrador and disseminate mushrooms.