Stylish Speed Curriculum Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chrysler, Dodge, Plymouth Brakes

CHRYSLER, DODGE, PLYMOUTH BRAKES After Ford started build- mouth, the medium ing horseless carriages, priced DeSoto, and the many other people saw high priced Chrysler. their potential and they Soon after that, Chrysler started building similar purchased the Dodge vehicles. Engineers and Brothers Automobile and stylists formed many of Truck Company, and the the early companies so Dodge also became a they were building nice medium priced car just cars, but the companies below DeSoto. All of the didn’t have a coherent 1935 Chrysler Airflow Chrysler truck offerings business plan. Some of the early companies were marketed under the Dodge name and that has- merged together for strength and that didn’t nec- n’t changed. General Motors used the hierarchy essarily help their bottom line. One of the early principal and it was working well for the Company, companies that started having financial problems so Chrysler borrowed the idea. was the Maxwell-Chalmers Company. Walter P. Chrysler was asked to reorganize the company Chrysler ran into a situation in the early ‘30s when and make it competitive. Chrysler did that with the their advanced engineering and styling created an Willys brand and the company became competi- unexpected problem for the Company. Automotive tive and lasted as a car company until the ‘50s. stylists in the late-’20s were using aerodynamics to The company is still around today as a Jeep man- make the early cars less wind resistant and more ufacturer that is currently owned by Chrysler. On fuel-efficient. Chrysler started designing a new car June 6, 1925, the Maxwell-Chalmers Company with that idea in mind that was very smooth for the was reorganized into the Chrysler Company and time period and in 1934 they marketed the car as the former name was dropped and the new car the Chrysler Airflow. -

Walter P. Chrysler Museum to Host First-Ever Collection of Chrysler Classic, Custom and Concept Vehicles

Contact: Jeanne Schoenjahn Walter P. Chrysler Museum to Host First-Ever Collection of Chrysler Classic, Custom and Concept Vehicles April 6, 2004, Auburn Hills, Mich. - Inspired Chrysler Design: The Art of Driving runs May 27 – Sept. 19, 2004 Extraordinary Chrysler automobiles spanning eight decades Retrospective heralds introduction of 2005 Chrysler 300 The Walter P. Chrysler Museum will present Inspired Chrysler Design: The Art of Driving,an all-Chrysler special exhibition featuring extraordinary cars spanning eight decades, Thursday, May 27 - Sunday, Sept. 19, 2004. The exhibition will showcase vehicles recognized for design and engineering excellence from distinguished private collections, the Museum Collection and the Chrysler Design Group. Among the more than 25 cars - including several one-of-a-kind models - assembled for Inspired Chrysler Design: The Art of Driving will be: 1924 Chrysler B-70 Phaeton 1928 Chrysler Model 72 LeMans Race Car (replica) 1932 Chrysler Imperial Speedster, custom-built for Walter P. Chrysler, Jr. 1932 Chrysler Imperial CL Limousine, custom-built for Walter P. Chrysler 1937 Chrysler Airflow Limousine, custom-built for Major Bowes, producer of one of the decade's most popular radio entertainment shows 1941 and 1993 Chrysler Thunderbolt concepts 1941 Chrysler Newport Phaeton concept 1995 Chrysler Atlantic Coupe concept Vehicles will be exhibited in retrospective displays featuring original advertisements and fashion, design and color elements representing each automobile's era. Original Design Office artwork and contemporary photographs of vintage Chrysler cars will round out the exhibition. "This is the first-ever all-Chrysler exhibition and it's clearly overdue," said Walter P. Chrysler Museum Manager Barry Dressel. -

Null: 2005 Chrysler Brand (Outside North America)

Contact: Michele Callender Ariel Gavilan Chrysler Heritage (Outside North America) Press kit translations are available in pdf format to the right under "Attached Documents." February 28, 2005, Auburn Hills, Mich. - The year 2004 was a landmark year for the Chrysler brand, with a fantastic display of new vehicles, model improvements and growing quality and technological prowess. In the year that marked the Chrysler brand’s 80th anniversary, the brand introduced seven new or refreshed models to markets outside of North America. Chrysler has repeatedly introduced unconventional vehicles and engineering innovations. Those innovations range from the Chrysler Six, which in 1924 redefined what a passenger car should be, to cab-forward designs and segment- defining MPVs that helped crystallise the brand’s image in the 1990s, to exciting current products like the Chrysler 300C Sedan, Touring and SRT8. The influence of the Chrysler brand’s past upon its future manifests itself in every new Chrysler product. Chrysler Brand Historical Highlights 1924: Walter P. Chrysler introduces the 1924 Chrysler Six — one of the most advanced and exciting cars of its day. The Chrysler Six is a quality light car — power in a small package — something no other brand is offering at the time. The vehicle makes maximum use of a high-speed, high-compression engine with incredible power and small displacement — along with other features such as hydraulic brakes. This becomes the first modern automobile at a very moderate price — a revolutionary concept in its day. 1925-1933: Chrysler broadens the model line to four separate series. Imperial emerges as a top-level luxury/performance car. -

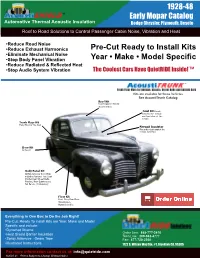

Pre-Cut Ready to Install Kits Year • Make • Model Specific 1928-48

1928-48 Early Mopar Catalog Automotive Thermal Acoustic Insulation Dodge Chrysler, Plymouth, Desoto Roof to Road Solutions to Control Passenger Cabin Noise, Vibration and Heat •Reduce Road Noise •Reduce Exhaust Harmonics Pre-Cut Ready to Install Kits •Eliminate Mechanical Noise •Stop Body Panel Vibration Year • Make • Model Specific •Reduce Radiated & Reflected Heat •Stop Audio System Vibration The Coolest Cars Have QuietRIDE Inside! ™ Kits are available for these Vehicles See AcoustiTrunk Catalog Roof Kit Roof & Quarter Panels above beltline. Cowl Kit Panels between the firewall and front door of the vehicle. Trunk Floor Kit Trunk Floor & Tire Well Firewall Insulator Fits under dash against the firewall bulkhead. Door Kit All Doors Body Panel Kit All Panels below the beltline including Package Tray, Seat Divider, Rear Wheel Wells, Fenders, Rear Quarters and Tail Panels (As Required) Floor Kit Front Floor, Rear Floor, Transmission Hump/ Driveline Everything in One Box to Do the Job Right! Pre-Cut, Ready To install Kits are Year, Make and Model Specific and include: •Dynamat Xtreme •Heat Shield Barrier Insulation Order Line: 888-777-3410 Tech Line: 209-942-4777 •Spray Adhesive •Seam Tape Fax: 877-720-2360 •Illustrated Instructions 1122 S. Wilson Way Ste. #1, Stockton CA, 95205 For more information contact us at: [email protected] ©2003-21 •Prices Subject to Change Without Notice 1935-2014 1928-48 Ram/Dodge Truck Catalog Early Mopar Catalog Automotive Thermal Acoustic Insulation Dodge Chrysler, Plymouth, Desoto Roof to Road Solutions to Control Passenger Cabin Noise, Vibration and Heat Introducing a multi-stage, automotive insulation and sound damping system to give MOPAR cars the “quiet riding comfort” found in today’s new cars. -

The Heritage of Chrysler

© FCA US Celebrate The Heritage of Chrysler 90 YEARS OF CHRYSLER | PROFILE IN LEADERSHIP An Unlikely Hero hrysler survived the death of its founder, the Great Depression and World C War II only to be weakened nearly to the point of collapse. The forces that would threaten Chrysler’s existence began build- into the fire.” ing in the 1970s, the same decade A whopping $1.5 billion in loan in which its unexpected savior guarantees from the U.S. govern- was ousted as the president of a ment certainly helped him take competing automaker. the heat. That infusion of money gave Chrysler an opportunity to develop two vehicles that would A NEW ERA Although Chrysler made become synonymous with the high-horsepower muscle cars company — and success: the that enthusiasts loved, the hey K-car, whose platform was intro- day for such vehicles was in the- duced in 1981, and the minivan, rear-view mirror by the ‘70s. which changed the world of auto- Emissions and safety standards mobiles when it arrived in 1984. were getting stricter, insurance Between those two milestones, rates were on the rise, and con- Chrysler returned $813,487,500 to sumers were looking for more the administration that gave it a affordable vehicles. In 1973, the new lease on life. oil embargo and its accompany ing fuel shortages motivated - SUCCESS Chrysler to focus on producing Under Iacocca’s guidance, mid-size and smaller models. Chrysler not only survived, it Despite that shift in product flourished. It acquired American planning, the company still need- Motors Corp, the fourth-largest ed help. -

Spring 2015 Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA

Spring 2015 Pacific Northwest Region - CCCA PNR CCCA Region Events 2015 CCCA National Events Details can be obtained by contacting the Event Annual Meeting 2015 Manager. If no event manager is listed, contact the sponsoring organization. March 7 - 11 ................Savannah,GA Grand Classics® April 18th -- Garage Tour May 29 -31 ......... CCCA Museum Experience PNR Contact: Jeff Clark July 19 ........................Oregon Region May 9th -- South Prairie Fly-In - Buckley CARavans PNR Contact: Bill Allard June 10-18 ............Pacific Northwest Region May 24th -- Staycation at Ste. Michelle PNR Contact: Bill Smallwood Director's Message June 21st -- Fathers’ Day at the Locks - Seattle Spring (plus just a bit) PNR Contact: Don Reddaway is here and the weather looks to cooperate, if July 4th -- Yarrow Point Parade not exactly today, then PNR Contact: Al McEwan in the very near future. An extra punch of the July 11th -- Picnic At Dochnahl's Vineyard Bijur system may still PNR Contact: Denny Dochnahl be in order but, for the most part, we have a lot of fine days for driving Classics July 17th - 20th -- Driving Tour to Forrest Grove in the coming months. Just remember the thirty premier PNR Contact: Bob Newlands & Jan Taylor motor vehicles that motored in for the Holiday Party. That was DECEMBER in the PACIFIC NORTHWEST! August 3rd -- Pebble Beach Kick-Off Party It is true; we have been mostly ensconced inside for the PNR Contact: Ashley Shoemaker past 3 months, but it is time to spin the wheels again. The Oregon Region is hosting a Grand Classic in September 5th -- Crescent Beach Concours 2015 in conjunction with the Forest Grove Concours PNR Contact: Colin Gurnsey d’Elegance. -

Chrysler Brand Heritage Chronology

Contact: Brandt Rosenbusch Chrysler Brand Heritage Chronology 1875-1912: Kansas-born Walter Chrysler, son of a locomotive engineer, was connected to the transportation industries throughout his life. His love of machinery prompted him to forsake a college education for a machinist’s apprenticeship, and his early career comprised numerous mechanical jobs in the railroad industry. 1912-1920: In 1912, Chrysler joined General Motors as manager of its Buick manufacturing plant, becoming president of the Buick division four years later. After parting ways with GM in 1919, Chrysler began a second career as a “doctor of ailing automakers,” strengthening first Willys-Overland, then the Maxwell Motor Corporation. 1920-1924: Chrysler teamed up with three ex-Studebaker engineers, Fred Zeder, Owen Skelton and Carl Breer, to design a revolutionary new car. They defined what the products of the Chrysler brand would be – affordable “luxury” vehicles known for innovative, top-flight engineering. 1924: The first was the 1924 Chrysler Six, an all-new car priced at $1,565 that featured two significant innovations – a light, powerful, high-compression six-cylinder engine and the first use of four-wheel hydraulic brakes in a moderately priced vehicle. The well-equipped Chrysler Six also featured aluminum pistons, replaceable oil and air filters, full- pressure lubrication, tubular front axles, shock absorbers and indirect interior lighting. 1925: After securing a $5,000,000 loan to start production, Chrysler sold over 32,000 units of the Chrysler Six in its first year. The Maxwell company soon had a new name: Chrysler Corporation. In 1925, the firm boasted more than 3, 800 dealers, sold over 100,000 cars and ranked fifth in the industry. -

1974 Gus Linder Sprint Car 1956

July 15th,16th,17th,2021 th 20 Annual Classic & Antique Auction Dear Friends and Customers, Another year has passed and we are very pleased to put last years Classic Sale in to the books as one of our best, thanks to the wonderful support of our participating clients. As we look forward to this years event, the Miller Family would like to sincerely thank all of the attendees and our staff for the success of this event in the past and we are committed to making this, our 20th, the best one yet! 225 units Friday and 175 units on Saturday Over 650 registered and qualified bidders expected 4% Buyer/Seller commission - $500 minimum/$2,500 maximum (some of the lowest fees in the industry) Car Corral with 200 spaces available. ($100 for 1 day or $150 for 2 days) Check/titles available within 10 minutes of the transaction to qualified buyers and sellers No fee motor home/trailer parking (hard surface) with dumping facilities & fresh water Conveniently located at Exit 178 of I-80 in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania (800) 248-8026 Schedule of Events Thursday July 15th, 2021 7:00pm-11:00pm Buyers/Sellers Cocktail Reception at Grant’s Place With Live Country Entertainment! Great Food and Libations, All Complimentary! Friday July 16th, 2021 9:00am-6:00pm Auction Offering 225 Vehicles 7:00pm-12:00 midnight VIP GALA CELEBRATION at Grant’s Place With “The Impact Band” Great Food & Libations, All Complimentary! Saturday July 17th, 2021 9:00am-4:00pm Auction Offering 175 Vehicles Please visit our website www.cpaautoauction.com for pictures of consignments and bidder registration forms for on-site, telephone and absentee bidding. -

My Love Affair with Dad's Cars by Steve White Dad Honed His Skills As

My Love Affair With Dad’s Cars By Steve White Dad honed his skills as a young mechanic-machinist in the late 1920s and early 30s at an upscale garage in the wealthy enclave of Piedmont, a suburb of Oakland, California. When I was young, he regaled me with stories of the cars he worked on there, including Packards, Cadillacs, Pierce-Arrows, and Duesenbergs. But his favorite was the Wills St. Claire, an obscure brand of very fine cars, two of which he actually came to own during the Great Depression when the value of everything plummeted. This was to be the beginning of Dad’s own love affair with cars, a lust that would have far-reaching consequences for his son. The first of Dad’s cars that I actually remember was his 1933 Terraplane 8 Roadster. I was just three when I found the keys to that car and with great difficulty got the starter motor turning. The sound was enough to get Dad’s immediate attention, which earned me a painful lesson. That was long before a spanking was a criminal offense. In 1940, Dad traded the Terraplane for a car that would see the family through WWII and the early years of the Cold War. It was a 1934 Chrysler Airflow CV Imperial Coupe. One can see that Dad’s appreciation of the unusual was standing the test of time. Immediately following Pearl Harbor, our family of four (Dad, Mom, my sister, Nancy, and me) moved from the peaceful valley town of Modesto to the bustling navy town of Vallejo, where Dad joined the workforce at Mare Island Naval Shipyard to help build the Arsenal of Democracy. -

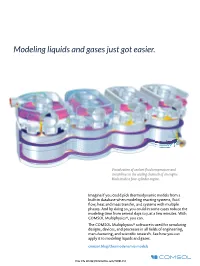

Modeling Liquids and Gases Just Got Easier

AE COMSOL Ad 0119.qxp_Layout 1 12/18/18 6:36 PM Page 1 Modeling liquids and gases just got easier. Visualization of coolant fluid temperature and streamlines in the cooling channels of an engine block inside a four-cylinder engine. Imagine if you could pick thermodynamic models from a built-in database when modeling reacting systems, fluid flow, heat and mass transfer, and systems with multiple phases. And by doing so, you could in some cases reduce the modeling time from several days to just a few minutes. With COMSOL Multiphysics®, you can. The COMSOL Multiphysics® software is used for simulating designs, devices, and processes in all fields of engineering, manufacturing, and scientific research. See how you can apply it to modeling liquids and gases. comsol.blog/thermodynamic-models Free Info at http://info.hotims.com/73001-714 AUTOMOTIVE ENGINEERING® Pickup Shocker! Startup Rivian Automotive aims to beat Detroit with the first electric full-size pickup New simulation solutions Innovations in Plastics Heat pump tech for EVs January 2019 autoengineering.sae.org AE dSPACE Ad 0119.qxp_Layout 1 12/18/18 6:37 PM Page 1 www.dspaceinc.com Functions for Autonomous Driving – Faster Development with dSPACE The idea of self-driving vehicles offers great potential for innovation. However, the development effort has to stay manageable despite increasing complexity. The solution is to use a well-coordinated tool chain for function development, virtual validation, hardware-in-the-loop simulation and data logging in the vehicle. Whether you are developing software functions, modeling vehicles, HQYLURQPHQWVHQVRUVDQGWUDIƂFVFHQDULRVRUUXQQLQJYLUWXDOWHVWGULYHVRQ 3&FOXVWHUVWKHVHDFWLYLWLHVFDQEHPDQDJHGHIƂFLHQWO\ZLWKSHUIHFWO\ matched tools that interact smoothly throughout all development steps. -

Sensuous Steel

/ May 31, 2013 ICONS 'Sensuous Steel' Comes to Nashville Visitors to "Sensuous Steel: Art Deco Cars," opening June 14 at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tenn., may wonder how any stylistic term could blanket the 19 automobiles and two motorcycles featured in the exhibit. By DAN NEIL As a critical term, Art Deco is famously imprecise and never more so than when applied to cars. Visitors to "Sensuous Steel: Art Deco Cars," opening June 14 at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, Tenn., may wonder how any stylistic term could blanket the 19 automobiles and two motorcycles featured in the exhibit. The Shah of Iran's glorious, idolatrous 1939 Bugatti Type 57C—custom-bodied by the French carrosserie VanVooren, a blown-glass vase of a car with chrome whitecaps licking at the fenders—would seem to have almost nothing in common with the sober, streamlined 1936 Chrysler Airflow. Peter Harholdt/Petersen Automotive Museum, Los Angeles 1939 Bugatti Type 57C by Vanvooren The fault line in Art Deco automobiles is rationalism, the commitment to evidence-based, function- forward design balanced against, and often subordinated to, the chic, the sculptural, the stylish. Critic Bevis Hiller suggested it was the space between Art Deco's "feminine, somewhat conservative style of 1925 … and the masculine reaction of the '30s, with its machine-age symbolism and use of new materials." Indeed, it's helpful to consider these objects along a continuum of Art Deco androgyny. On one side is the exhibit's Henderson KJ Streamliner (1930), a low-slung two-wheeler wrapped nose-to- tail in a voluptuous teardrop fairing—unworkable, unrideable and representing mere aerodynamic guesswork. -

1936 Diecast Toys and Diecast Scale Model Cars

1936 diecast toys and diecast scale model cars Toy Wonders diecast scale model cars Catalog of 1936 diecast for wholesalers and retailers only 1936 diecast Created on 8/20/2009 Products found: 16 Jada Toys Dub City Oldskool - Wave 1 (1:64, Asstd.) 12037W1 Item# 12037W1 Mattel Matchbox - Lincoln Zephyr Convertible (1936, 4.75", Lite Green) K1876 Item# K1876 Signature Models - Chrysler Airflow (1936, 1:18, Silver) 18126 Item# 18126SV Signature Models - Chrysler Airflow (1936, 1:32, Black) 32306BK Item# 32306BK Signature Models - Chrysler Airflow (1936, 1:32, Silver) 32306SV Item# 32306SV Signature Models - Cord 810 (1936, 1:18, Black) 18108 Item# 18108BK Signature Models - Cord 810 (1936, 1:18, White) 18108 Item# 18108W http://www.toywonders.com/productcart/pc/showsearchre...tyle=p&withStock=-1&resultCnt=25&keyword=1936+diecast (1 of 2) [8/20/2009 1:13:32 PM] 1936 diecast toys and diecast scale model cars Signature Models - Cord 810 Soft Top (1936, 1:18, Yellow) 18108 Item# 18108YL Signature Models - Cord 812 Supercharged (1936, 1:18, Burgundy) 18112 Item# 18112BG Signature Models - Lincoln Zephyr (1939, 1:18, Black) 18102 Item# 18102BK Signature Models - Pontiac Deluxe Hard Top (1936, 1:18, Green) 18106 Item# 18106GN Signature Models - Pontiac Deluxe Police Car (1936, 1:18, Black) 18140 Item# 18140BK Signature Models Charlestown - Chrysler Airflow Police Car (1936, 1:18, Cafe) 68626 Item# 68626CF Welly - Ford Deluxe Cabriolet Convertible (1936, 1:18, Black) 19867 Item# 19867BK Welly - Ford Deluxe Cabriolet Convertible (1936, 1:18, Blue)