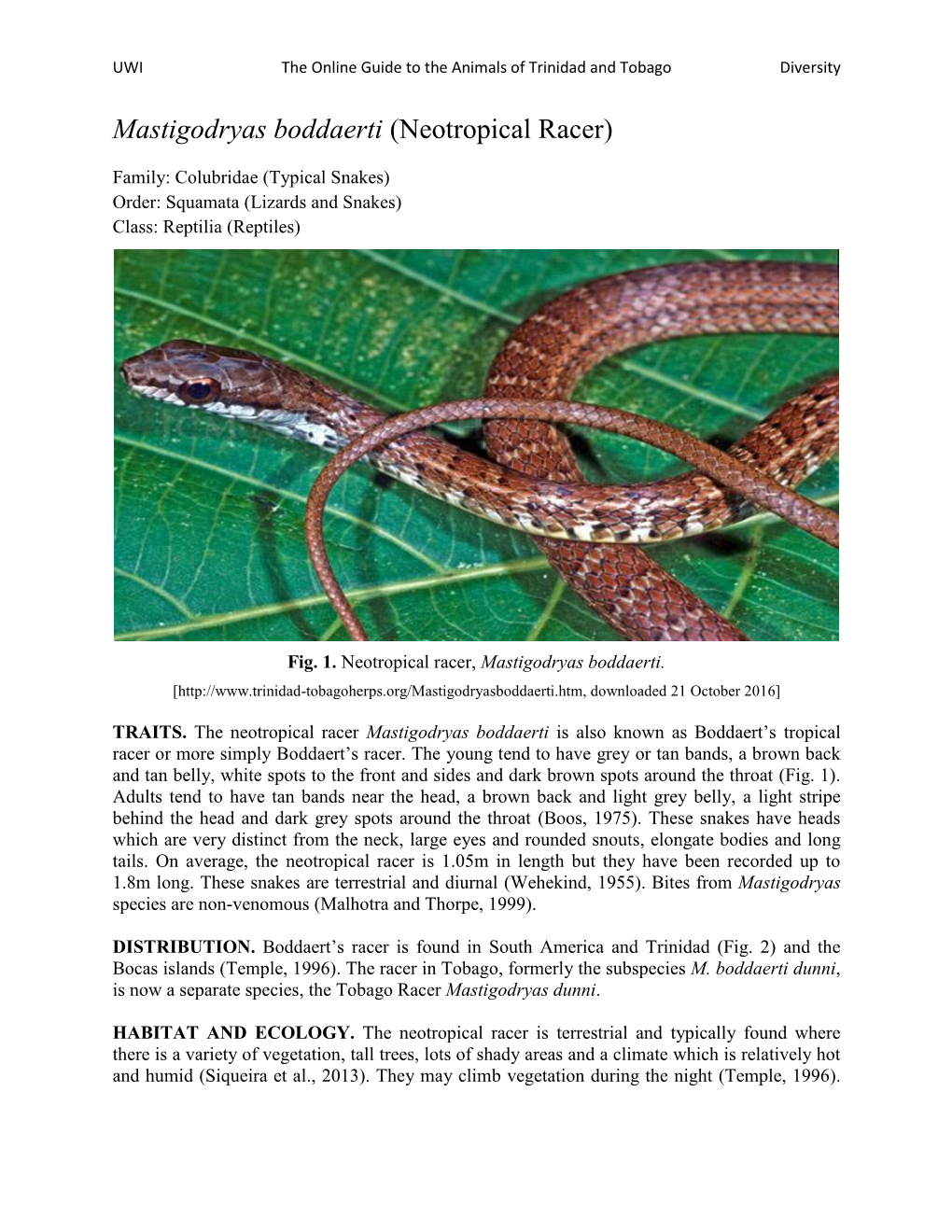

Mastigodryas Boddaerti (Neotropical Racer)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

HERPETOLOGICAL BULLETIN Number 106 – Winter 2008

The HERPETOLOGICAL BULLETIN Number 106 – Winter 2008 PUBLISHED BY THE BRITISH HERPETOLOGICAL SOCIETY THE HERPETOLOGICAL BULLETIN Contents RESEA R CH AR TICLES Use of transponders in the post-release monitoring of translocated spiny-tailed lizards (Uromastyx aegyptia microlepis) in Abu Dhabi Emirate, United Arab Emirates Pritpal S. Soorae, Judith Howlett and Jamie Samour .......................... 1 Gastrointestinal helminths of three species of Dicrodon (Squamata: Teiidae) from Peru Stephen R. Goldberg and Charles R. Bursey ..................................... 4 Notes on the Natural History of the eublepharid Gecko Hemitheconyx caudicinctus in northwestern Ghana Stephen Spawls ........................................................ 7 Significant range extension for the Central American Colubrid snake Ninia pavimentata (Bocourt 1883) Josiah H. Townsend, J. Micheal Butler, Larry David Wilson, Lorraine P. Ketzler, John Slapcinsky and Nathaniel M. Stewart ..................................... 15 Predation on Italian Newt larva, Lissotriton italicus (Amphibia, Caudata, Salamandridae), by Agabus bipustulatus (Insecta, Coleoptera, Dytiscidae) Luigi Corsetti and Gianluca Nardi........................................ 18 Behaviour, Time Management, and Foraging Modes of a West Indian Racer, Alsophis sibonius Lauren A. White, Peter J. Muelleman, Robert W. Henderson and Robert Powell . 20 Communal egg-laying and nest-sites of the Goo-Eater, Sibynomorphus mikanii (Colubridae, Dipsadinae) in southeastern Brazil Henrique B. P. Braz, Francisco L. Franco -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

Snakes: Cultural Beliefs and Practices Related to Snakebites in a Brazilian Rural Settlement Dídac S Fita1, Eraldo M Costa Neto2*, Alexandre Schiavetti3

Fita et al. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2010, 6:13 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/6/1/13 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access ’Offensive’ snakes: cultural beliefs and practices related to snakebites in a Brazilian rural settlement Dídac S Fita1, Eraldo M Costa Neto2*, Alexandre Schiavetti3 Abstract This paper records the meaning of the term ‘offense’ and the folk knowledge related to local beliefs and practices of folk medicine that prevent and treat snake bites, as well as the implications for the conservation of snakes in the county of Pedra Branca, Bahia State, Brazil. The data was recorded from September to November 2006 by means of open-ended interviews performed with 74 individuals of both genders, whose ages ranged from 4 to 89 years old. The results show that the local terms biting, stinging and pricking are synonymous and used as equivalent to offending. All these terms mean to attack. A total of 23 types of ‘snakes’ were recorded, based on their local names. Four of them are Viperidae, which were considered the most dangerous to humans, besides causing more aversion and fear in the population. In general, local people have strong negative behavior towards snakes, killing them whenever possible. Until the antivenom was present and available, the locals used only charms, prayers and homemade remedies to treat or protect themselves and others from snake bites. Nowadays, people do not pay attention to these things because, basically, the antivenom is now easily obtained at regional hospitals. It is under- stood that the ethnozoological knowledge, customs and popular practices of the Pedra Branca inhabitants result in a valuable cultural resource which should be considered in every discussion regarding public health, sanitation and practices of traditional medicine, as well as in faunistic studies and conservation strategies for local biological diversity. -

Reproductive Biology of the Swamp Racer Mastigodryas Bifossatus (Serpentes: Colubridae) in Subtropical Brazil

Reproductive biology of the swamp racer Mastigodryas bifossatus (Serpentes: Colubridae) in subtropical Brazil Pedro T. Leite 1; Simone de F. Nunes 1; Igor L. Kaefer 1, 2 & Sonia Z. Cechin 1 1 Laboratório de Herpetologia, Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria. Faixa de Camobi, Km 9, 97105-900 Santa Maria, Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 2 Corresponding author. ABSTRACT. The swamp racer Mastigodryas bifossatus (Raddi, 1820) is a large snake of Colubrinae. It is widely distributed in open areas throughout South America. Dissection of 224 specimens of this species housed in herpetological collections of the southern Brazilian states of Rio Grande do Sul, Santa Catarina and Paraná provided information on its sexual dimor- phism, reproductive cycle and fecundity in subtropical Brazil. Adult specimens of M. bifossatus average approximately 1190 mm in snout-vent length and females are larger than males. The reproductive cycle of females is seasonal, with secondary vitellogenesis occurring from July to December. However, examination of male gonads did not reveal signs of reproductive seasonality in this sex. Egg laying was recorded from November to January. The estimated recruitment period extends from February to April. The mean number of individuals per clutch is 15, and there is a positive correlation between female length and clutch size. KEY WORDS. Fecundity; neotropics; reproduction; reproductive cycle; sexual dimorphism. Mastigodryas Amaral, 1935 belongs to Colubrinae and and fecundity of M. bifossatus (morphotype M. b. bifossatus) contains large-sized, generally robust species, active during the from subtropical domains of Brazil. -

A Serpentes Atual.Pmd

VOLUME 18, NÚMERO 2, NOVEMBRO 2018 ISSN 1519-1982 Edição revista e atualizada em julho de 2019 BIOLOGIA GERAL E EXPERIMENTAL VERTEBRADOS TERRESTRES DE RORAIMA IV. SERPENTES BOA VISTA, RR Biol. Geral Exper. 3 BIOLOGIA GERAL E EXPERIMENTAL EDITORES EDITORES ASSOCIADOS Celso Morato de Carvalho – Instituto Nacional de Adriano Vicente dos Santos– Centro de Pesquisas Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Am - Necar, Ambientais do Nordeste, Recife, Pe UFRR, Boa Vista, Rr Edson Fontes de Oliveira – Universidade Tecnológica Jeane Carvalho Vilar – Aracaju, Se Federal do Paraná, Londrina, Pr Everton Amâncio dos Santos – Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brasília, D.F. Francisco Filho de Oliveira – Secretaria Municipal da Educação, Nossa Senhora de Lourdes, Se Biologia Geral e Experimental é indexada nas Bases de Dados: Latindex, Biosis Previews, Biological Abstracts e Zoological Record. Edição eletrônica: ISSN 1980-9689. www.biologiageralexperimental.bio.br Endereço: Biologia Geral e Experimental, Núcleo de Estudos Comparados da Amazônia e do Caribe, Universidade Federal de Roraima, Campus do Paricarana, Boa Vista, Av. Ene Garcez, 2413. E-mail: [email protected] ou [email protected] Aceita-se permuta. 4 Vol. 18(2), 2018 BIOLOGIA GERAL E EXPERIMENTAL Série Vertebrados Terrestres de Roraima. Coordenação e revisão: CMorato e SPNascimento. Vol. 17 núm. 1, 2017 I. Contexto Geográfico e Ecológico, Habitats Regionais, Localidades e Listas de Espécies. Vol. 17 núm. 2, 2017 II. Anfíbios. Vol. 18 núm. 1, 2018 III. Anfisbênios e Lagartos. Vol. 18 núm. 2, 2018 IV. Serpentes. Vol. 18 núm. 3, 2018 V. Quelônios e Jacarés. Vol. 19 núm. 1, 2019 VI. Mamíferos não voadores. Vol. 19 núm. -

Reproductive Biology and Food Habits of the Swamp Racer Mastigodryas Bifossatus from Southeastern South America

HERPETOLOGICAL JOURNAL 17: 104–109, 2007 Reproductive biology and food habits of the swamp racer Mastigodryas bifossatus from southeastern South America Otavio A.V. Marques1 & Ana Paula Muriel2 1Laboratório de Herpetologia, Instituto Butantan, São Paulo, SP, Brazil 2Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Campinas, SP, Brazil The swamp racer Mastigodryas bifossatus is a large colubrid snake distributed mainly in open areas in South America. Dissection of 242 specimens provided data on body sizes, sexual size dimorphism, reproductive cycles and food habits of this species. Adult M. bifossatus average approximately 1100 mm in snout–vent length, with males and females attaining similar sizes. Reproductive cycles in females seem to be continuous, although oviductal eggs occur mainly from the beginning to the middle of the rainy season with peak recruitment at the end of the rainy season. Clutch size ranges from four to 24 and each newborn individual is about 300 mm SVL. Mastigodryas bifossatus is euryphagic, feeding mainly on frogs (44%) and mammals (32%). Lizards (16%), birds (4%) and snakes (4%) form the remaining prey. Relatively small prey (0.05–0.019) are ingested by adults, and juveniles eat mammals, which suggests that there is no ontogenetic shift in the diet of this snake. Swamp racers forage by day on the ground in open areas but may use arboreal substrates for sleeping or basking. Key words: Brazil, Colubrinae, diet, reproductive cycles, sexual dimorphism INTRODUCTION characterized by two distinct seasons: a dry season from April to August, with less rainfall and lower temperatures, he snakes of the subfamily Colubrinae are widely dis- and a rainy one from September to March, with higher Ttributed over all landmasses of the world, but are rainfall and temperatures (Nimer, 1989). -

Reptile Diversity in an Amazing Tropical Environment: the West Indies - L

TROPICAL BIOLOGY AND CONSERVATION MANAGEMENT - Vol. VIII - Reptile Diversity In An Amazing Tropical Environment: The West Indies - L. Rodriguez Schettino REPTILE DIVERSITY IN AN AMAZING TROPICAL ENVIRONMENT: THE WEST INDIES L. Rodriguez Schettino Department of Zoology, Institute of Ecology and Systematics, Cuba To the memory of Ernest E. Williams and Austin Stanley Rand Keywords: Reptiles, West Indies, geographic distribution, morphological and ecological diversity, ecomorphology, threatens, conservation, Cuba Contents 1. Introduction 2. Reptile diversity 2.1. Morphology 2.2.Habitat 3. West Indian reptiles 3.1. Greater Antilles 3.2. Lesser Antilles 3.3. Bahamas 3.4. Cuba (as a study case) 3.4.1. The Species 3.4.2. Geographic and Ecological Distribution 3.4.3. Ecomorphology 3.4.4. Threats and Conservation 4. Conclusions Acknowledgments Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary The main features that differentiate “reptiles” from amphibians are their dry scaled tegument andUNESCO their shelled amniotic eggs. In– modern EOLSS studies, birds are classified under the higher category named “Reptilia”, but the term “reptiles” used here does not include birds. One can externally identify at least, three groups of reptiles: turtles, crocodiles, and lizards and snakes. However, all of these three groups are made up by many species that are differentSAMPLE in some morphological characters CHAPTERS like number of scales, color, size, presence or absence of limbs. Also, the habitat use is quite variable; there are reptiles living in almost all the habitats of the Earth, but the majority of the species are only found in the tropical regions of the world. The West Indies is a region of special interest because of its tropical climate, the high number of species living on the islands, the high level of endemism, the high population densities of many species, and the recognized adaptive radiation that has occurred there in some genera, such as Anolis, Sphaerodactylus, and Tropidophis. -

From Four Sites in Southern Amazonia, with A

Bol. Mus. Para. Emílio Goeldi. Cienc. Nat., Belém, v. 4, n. 2, p. 99-118, maio-ago. 2009 Squamata (Reptilia) from four sites in southern Amazonia, with a biogeographic analysis of Amazonian lizards Squamata (Reptilia) de quatro localidades da Amazônia meridional, com uma análise biogeográfica dos lagartos amazônicos Teresa Cristina Sauer Avila-PiresI Laurie Joseph VittII Shawn Scott SartoriusIII Peter Andrew ZaniIV Abstract: We studied the squamate fauna from four sites in southern Amazonia of Brazil. We also summarized data on lizard faunas for nine other well-studied areas in Amazonia to make pairwise comparisons among sites. The Biogeographic Similarity Coefficient for each pair of sites was calculated and plotted against the geographic distance between the sites. A Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity was performed comparing all sites. A total of 114 species has been recorded in the four studied sites, of which 45 are lizards, three amphisbaenians, and 66 snakes. The two sites between the Xingu and Madeira rivers were the poorest in number of species, those in western Amazonia, between the Madeira and Juruá Rivers, were the richest. Biogeographic analyses corroborated the existence of a well-defined separation between a western and an eastern lizard fauna. The western fauna contains two groups, which occupy respectively the areas of endemism known as Napo (west) and Inambari (southwest). Relationships among these western localities varied, except between the two northernmost localities, Iquitos and Santa Cecilia, which grouped together in all five area cladograms obtained. No variation existed in the area cladogram between eastern Amazonia sites. The easternmost localities grouped with Guianan localities, and they all grouped with localities more to the west, south of the Amazon River. -

A Serpentes Atual.Pmd

VOLUME 18, NÚMERO 2, NOVEMBRO 2018 ISSN 1519-1982 Edição revista e atualizada em julho de 2019 BIOLOGIA GERAL E EXPERIMENTAL VERTEBRADOS TERRESTRES DE RORAIMA IV. SERPENTES BOA VISTA, RR Biol. Geral Exper. 3 BIOLOGIA GERAL E EXPERIMENTAL EDITORES EDITORES ASSOCIADOS Celso Morato de Carvalho – Instituto Nacional de Adriano Vicente dos Santos– Centro de Pesquisas Pesquisas da Amazônia, Manaus, Am - Necar, Ambientais do Nordeste, Recife, Pe UFRR, Boa Vista, Rr Edson Fontes de Oliveira – Universidade Tecnológica Jeane Carvalho Vilar – Aracaju, Se Federal do Paraná, Londrina, Pr Everton Amâncio dos Santos – Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brasília, D.F. Francisco Filho de Oliveira – Secretaria Municipal da Educação, Nossa Senhora de Lourdes, Se Biologia Geral e Experimental é indexada nas Bases de Dados: Latindex, Biosis Previews, Biological Abstracts e Zoological Record. Edição eletrônica: ISSN 1980-9689. www.biologiageralexperimental.bio.br Endereço: Biologia Geral e Experimental, Núcleo de Estudos Comparados da Amazônia e do Caribe, Universidade Federal de Roraima, Campus do Paricarana, Boa Vista, Av. Ene Garcez, 2413. E-mail: [email protected] ou [email protected] Aceita-se permuta. 4 Vol. 18(2), 2018 BIOLOGIA GERAL E EXPERIMENTAL Série Vertebrados Terrestres de Roraima. Coordenação e revisão: CMorato e SPNascimento. Vol. 17 núm. 1, 2017 I. Contexto Geográfico e Ecológico, Habitats Regionais, Localidades e Listas de Espécies. Vol. 17 núm. 2, 2017 II. Anfíbios. Vol. 18 núm. 1, 2018 III. Anfisbênios e Lagartos. Vol. 18 núm. 2, 2018 IV. Serpentes. Vol. 18 núm. 3, 2018 V. Quelônios e Jacarés. Vol. 19 núm. 1, 2019 VI. Mamíferos não voadores. Vol. 19 núm. -

St Vincent and the Grenadines

Important Bird Areas in the Caribbean – St Vincent and the Grenadines ■ ST VINCENT & THE GRENADINES LAND AREA 389 km2 ALTITUDE 0–1,234 m HUMAN POPULATION 102,250 CAPITAL Kingstown IMPORTANT BIRD AREAS 15, totalling 179 km2 IMPORTANT BIRD AREA PROTECTION 31% BIRD SPECIES 152 THREATENED BIRDS 6 RESTRICTED-RANGE BIRDS 14 LYSTRA CULZAC-WILSON (AVIANEYES) Ashton Lagoon IBA on Union Island in the southern Grenadines. (PHOTO: GREGG MOORE) INTRODUCTION Brisbane, 932 m) lies to the south of La Soufriere, and then Grand Bonhomme (970 m), Petit Bonhomme (756 m) and St Vincent and the Grenadines is a multi-island nation in the Mount St Andrew (736 m) are south of this. A large number Windward Islands of the Lesser Antillean chain. St Vincent is of very steep lateral ridges emanate from the central massif the main island (c.29 km long and 18 km wide, making up culminating in high, rugged and almost vertical cliffs on the c.88% of the nation’s land area) and lies furthest north, c.35 (eastern) leeward coast, while the windward coast is more km south-south-west of St Lucia. The chain of Grenadine gently sloping, with wider, flatter valleys. In contrast to St islands (comprising numerous islands, islets, rocks and reefs) Vincent, the Grenadines have a much gentler relief, with the extends south for 75 km towards the island of Grenada, with mountain peaks on these islands rising to150–300 m. There Union Island being the most southerly. Other major islands are no perennial streams in the Grenadines (although there is of the (St Vincent) Grenadines are Bequia (which is the a spring on Bequia), and unlike much of the mainland, these largest), Mustique, Canouan, Mayreau, Palm (Prune) Island islands are surrounded by fringing reefs and white sand and Petit St Vincent. -

Snake Communities Worldwide

Web Ecology 6: 44–58. Testing hypotheses on the ecological patterns of rarity using a novel model of study: snake communities worldwide L. Luiselli Luiselli, L. 2006. Testing hypotheses on the ecological patterns of rarity using a novel model of study: snake communities worldwide. – Web Ecol. 6: 44–58. The theoretical and empirical causes and consequences of rarity are of central impor- tance for both ecological theory and conservation. It is not surprising that studies of the biology of rarity have grown tremendously during the past two decades, with particular emphasis on patterns observed in insects, birds, mammals, and plants. I analyse the patterns of the biology of rarity by using a novel model system: snake communities worldwide. I also test some of the main hypotheses that have been proposed to explain and predict rarity in species. I use two operational definitions for rarity in snakes: Rare species (RAR) are those that accounted for 1% to 2% of the total number of individuals captured within a given community; Very rare species (VER) account for ≤ 1% of individuals captured. I analyse each community by sample size, species richness, conti- nent, climatic region, habitat and ecological characteristics of the RAR and VER spe- cies. Positive correlations between total species number and the fraction of RAR and VER species and between sample size and rare species in general were found. As shown in previous insect studies, there is a clear trend for the percentage of RAR and VER snake species to increase in species-rich, tropical African and South American commu- nities. This study also shows that rare species are particularly common in the tropics, although habitat type did not influence the frequency of RAR and VER species. -

First Report of Parasitism by Hexametra Boddaertii (Nematoda: Ascaridae

Veterinary Parasitology 224 (2016) 60–64 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Veterinary Parasitology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vetpar Short communication First report of parasitism by Hexametra boddaertii (Nematoda: Ascaridae) in Oxyrhopus guibei (Serpentes: Colubridae) a,∗ a b b a María E. Peichoto , Matías N. Sánchez , Ariel López , Martín Salas , María R. Rivero , c d e Pamela Teibler , Gislayne de Melo Toledo , Flávio L. Tavares a Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET), Ministerio de Ciencia Tecnología e Innovación Productiva; Instituto Nacional de Medicina Tropical (INMeT), Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, Neuquén y Jujuy s/n, 3370 Puerto Iguazú, Argentina b Instituto Nacional de Medicina Tropical (INMeT), Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, Neuquén y Jujuy s/n, 3370 Puerto Iguazú, Argentina c Universidad Nacional del Nordeste (UNNE), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias (FCV), Sargento Cabral 2139, 3400, Corrientes, Argentina d Universidade Estadual Paulista (UNESP), Campus de Botucatu, Instituto de Biociências, Departamento de Parasitologia, Botucatu, São Paulo, Brazil e Universidade Federal da Integrac¸ ão Latino-Americana (UNILA), Av. Silvio Américo Sasdelli, 1842 − Vila A, Foz do Iguac¸ u, PR, CEP 85866-000, Brazil a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: The current study summarizes the postmortem examination of a specimen of Oxyrhopus guibei (Serpentes, Received 1 November 2015 Colubridae) collected in Iguazu National Park (Argentina), and found deceased a week following arrival to Received in revised form 3 May 2016 the serpentarium of the National Institute of Tropical Medicine (Argentina). Although the snake appeared Accepted 13 May 2016 to be in good health, a necropsy performed following its death identified the presence of a large number of roundworms in the coelomic cavity, with indications of peritonitis and serosal adherence.