A Legacy of Learning and Research “I Believe in Living a Life That Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Casting Rodin’s Thinker Sand mould casting, the case of the Laren Thinker and conservation treatment innovation Beentjes, T.P.C. Publication date 2019 Document Version Other version License Other Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Beentjes, T. P. C. (2019). Casting Rodin’s Thinker: Sand mould casting, the case of the Laren Thinker and conservation treatment innovation. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:07 Oct 2021 Chapter 2 The casting of sculpture in the nineteenth century 2.1 Introduction The previous chapter has covered the major technical developments in sand mould casting up till the end of the eighteenth century. These innovations made it possible to mould and cast increasingly complex models in sand moulds with undercut parts, thus paving the way for the founding of intricately shaped sculpture in metal. -

Conference New Sculptors, Old Masters: the Victorian Renaissance of Italian Sculpture Friday 9 March 2019, 10.00–17.30 Henry Moore Lecture Theatre, Leeds Art Gallery

Conference New Sculptors, Old Masters: The Victorian Renaissance of Italian Sculpture Friday 9 March 2019, 10.00–17.30 Henry Moore Lecture Theatre, Leeds Art Gallery Programme 10.00–10.15 Welcome and Opening Remarks Dr Charlotte Drew (University of Bristol) 10.15–12.15 Site and Seeing: Encountering Italian Sculpture in the Nineteenth Century Chair: Dr Charlotte Drew (University of Bristol) 10.15–10.35 Prof. Martha Dunkelmann (Canisius College, Buffalo) ‘Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Donatello’ 10.35–10.55 Thomas Couldridge (Durham University) ‘South Kensington’s Cupid and Modern Receptions: A New Chapter’ 10.55–11.15 Discussion Chair: Dr Melissa Gustin (Henry Moore Institute) 11.15–11.35 Dr Deborah Stein (Boston College) ‘Charles Callahan Perkins’ Outline Illustrations of his Art Historical Scholarship on Early Italian Renaissance Sculpture’ 11.35–11.55 Dr Lynn Catterson (Columbia University, New York) ‘New Sculptors, New Old Masters: The Manufacture of Italian Renaissance Art in the Late Nineteenth-century Art Market’ 11.55–12.15 Discussion 12.15–13.30 Lunch 13.30–15.00 Italian Sculpture and the Decorative Chair: TBC 13.30–13.50 Dr Juliet Carroll (Liverpool John Moores University) ‘Encountering the Unique: The Della Robbia Pottery of Birkenhead and the Architectural Bas-reliefs of Luca della Robbia’ 13.50–14.10 Samantha Scott (University of York) ‘Lithophanes and the Italian Renaissance: Translation between Two and Three Dimensions’ 14.10–14.30 Dr Ciarán Rua O’Neill (University of York) ‘More Versatile than Most: Alfred Gilbert and Benvenuto Cellini’ 14.30–15.00 Discussion 15.00–15.30 Tea Break 15.30–17.00 Old Masters, New Mistresses Chair: Prof. -

Review of 'Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901' At

Review of ‘Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901’ at the Yale Center for British Art, 11 September to 30 November 2014 Jonathan Shirland Stepping out of the elevator onto the second floor, the trio demand attention immediately, and thereby recalibrate our (stereotyped) relation- ship to Victorian sculpture at a stroke. They are impossible to ignore, or walk past. Yet they are a difficult grouping, with the darkly coloured, male, full-length statue of James Sherwood Westmacott’s Saher de Quincy, Earl of Winchester of 1848–53 in uncertain relation to the two very different yet equally captivating busts of Victoria positioned to his left (Fig. 1). Francis Leggatt Chantrey’s rendering from 1840 makes the nineteen-year-old queen sexy: the animated mouth and nostrils, bare neck and shoulders, and subtle folding of the tiara into the plaits of hair reinforcing an exem- plary demonstration of the sensuality of marble. Yet, Alfred Gilbert’s mon- umental three-foot bust made between 1887 and 1889 for the Army & Navy Club in London looms over the shoulder of Chantrey’s young queen; the multiple textures, deep undercutting, and surface detail present an ageing Victoria at her most imposing. So what is Westmacott’s piece doing here as an adjunct to this pairing of sculptural portraits? The curators were perhaps keen to show off the first of their many coups by immediately pre- senting to us a novel sculptural encounter: Westmacott’s Earl is normally removed from close scrutiny, looking down on the chamber of the House of Lords from a niche twenty-five feet above the floor, alongside statues of seventeen other barons and prelates who in 1215 helped to secure the signing of the Magna Carta. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Alex Potts

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Alex Potts Date of Birth 1 October 1943 Education 1965 BA(Hons) in mathematics, physics and chemistry, University of Toronto, Canada: first class 1966 Diploma in Advanced Mathematics, University of Oxford l966-9 Research in theoretical chemistry at University of Oxford 197O Diploma in the History of Art, University of Oxford (special subject ‘Baudelaire and the Artists of his Time’): distinction l97O-3 Registered as a full-time research student in art history at the Warburg Institute, University of London l978 PhD, University of London (thesis title: Winckelmann's Interpretation of the History of Ancient Art in its Eighteenth Century Context) Teaching Appointments 1971-3 Part-time Lecturer in the Department of Fine Art, Portsmouth Polytechnic l973-81 Lecturer in the history of art at the University of East Anglia, Norwich l98l-9 Senior Lecturer in the history of art at Camberwell College of Arts; from 1984, Principal Lecturer; Acting Head of Department (Art History and Conservation) in 1987 and 1989 l984 Guest Professor for one term at the University of Osnabrück, Germany 1989-95 Senior Lecturer in the history of art and Head of Art History, Department of Historical and Cultural Studies, Goldsmiths College, University of London 1992 Visiting Professor for one month at University of California, Berkeley 1993 Visiting Professor for the Spring semester at University of California, Berkeley 1994 Visiting Professor for the Summer semester at University of California, Irvine 1996-2002 Professor of History of Art, -

London Sights

LONDON Basic data Capital of England and the United Kingdom Population: 14 million Fashion, educational, culinary, financial center SIGHTSEEING The Big Ben The Big Ben • Big Ben = the bell of the clock • Was built in 1858 • 96 m tall • Celebrated its 150th birthday in May 2009 Trafalgar Square NELSON´S COLUMN NELSON´S COLUMN • Nelson's Column is a monument in Trafalgar Square in the City of Westminster, Central London built to commemorate Admiral Horatio Nelson, who died at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805. The monument was constructed between 1840 and 1843 to a design by William Railton at a cost of £47,000 (equivalent to £4,532,261 in 2018); • The pedestal is decorated with four bronze relief panels, each 18 feet (5.5 m) square; Trafalgar Square Christmas Piccadily Circus EROS STAUE • Although the statue is generally known as Eros, it was created as an image of • The Shaftesbury his brother, Anteros.[2] The Memorial Fountain, sculptor Alfred Gilbert had also (mistakenly) known already sculpted a statue of as "Eros", is a fountain Anteros and, when surmounted by a winged commissioned for the Shaftesbury Memorial statue of Anteros, located Fountain, chose to reproduce at the southeastern side the same subject, who, as of Piccadilly Circus in "The God of Selfless Love" London, England. was deemed to represent the philanthropic 7th Earl of Shaftesbury suitably. Buckingham Palace Buckingham Palace • Official place of the royals (they don’t live there) • Today more a tourist attraction • Traditional Canging of the Guards takes place here Buckingham -

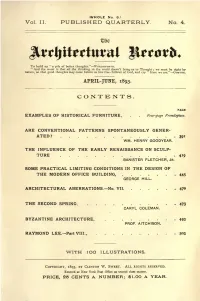

Architectural Record Publishing Department

(WHOLE No. 8.) Vol. II. PUBLISHED QUARTERLY. No. 4. TTbe To build "a of better WORDSWORTH. " up pile thoughts.'' And the worst is that all the in the world doesn't thinking us to ; we must be bring Thought" right by nature, so that good thoughts may come before us like free children of God, and cry Here we are." GOKTHB. APRIL-JUNE, 1893. CONTENTS. EXAMPLES OF HISTORICAL FURNITURE, . ... Four-page Frontispiece, ARE CONVENTIONAL PATTERNS SPONTANEOUSLY GENER- ATED ? .;,... 391 WM. HENRY GOODYEAR. THE INFLUENCE OF THE EARLY RENAISSANCE ON SCULP- TURE . ... .419 BANISTER FLETCHER, JR. SOME PRACTICAL LIMITING CONDITIONS IN THE DESIGN OF THE MODERN OFFICE BUILDING, 445 GEORGE HILL. ARCHITECTURAL ABERRATIONS. No. VII 47 THE SECOND SPRING 473 CARYL COLEMAN. BYZANTINE ARCHITECTURE, . 493 PROF. AITCHISON. RAYMOND LEE. Part VIII., . 5<>3 WITH 1OO ILLUSTRATIONS. COPYRIGHT, 1893, BY CLINTON W. SWEET. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. Entered at New York Post Office as second class matter. PRICE, 25 CENTS A NUMBER; $1.OO A YEAR. THE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD PUBLISHING DEPARTMENT, 14-16 Vesey Street, New York. HE ARCHITECTURAL RECORD takes pleasure in announc- ing that it has obtained the Sole Agency in the United States FOR THE SUPERB (OLLEGTION OP ISSUED BY THE NATIONAL GOVERNMENT OF FRANCE. Photographs (each 10x14 inches, unmounted) belonging to this collection will henceforth be for sale in the Art Department of this Magazine, at Nos. 14 and 16 Vesey Street, New York City. The for each price copy has been fixed at the lowest figure possible, viz. : sixty cents, or by the dozen, fifty cents each. To this sum must be added the cost of postage. -

Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901

Roberto C. Ferrari exhibition review of Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 1 (Spring 2015) Citation: Roberto C. Ferrari, exhibition review of “Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 1 (Spring 2015), http:// www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring15/ferrari-reviews-sculpture-victorious-art-in-an-age-of- invention. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Ferrari: Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 1 (Spring 2015) Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Connecticut September 11 – November 30, 2014 Catalogue: Sculpture Victorious: Art in an Age of Invention, 1837–1901 Edited by Martina Droth, Jason Edwards, and Michael Hatt New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014. 448 pp.; 303 color illustrations; biographies, bibliography, index. $80.00 ISBN: 978-0-300-20803-0 For modernists, the phrase “Victorian sculpture” likely conjures images of decaying monuments with historicized figures, or sentimental statuettes bordering on domestic kitsch. Art history has not helped this perception, as exemplified by the words of H. W. Janson, writing about sculpture produced in England during the reign of Victoria: “There can be no doubt that the -

Sculpture and Modernity in Europe, 1865-1914

ARTH 17 (02) S c u l p t u r e a n d M o d e r n i t y i n E u r o p e , 1 8 6 5 - 1 9 1 4 Professor David Getsy Department of Art History, Dartmouth College Spring 2003 • 11 / 11.15-12.20 Monday Wednesday Friday / x-hour 12.00-12.50 Tuesday office hours: 1.30-3.00 Wednesday / office: 307 Carpenter Hall c o u r s e d e s c r i p t i o n This course will examine the transformations in figurative sculpture during the period from 1865 to the outbreak of the First World War. During these years, sculptors sought to engage with the rapidly evolving conditions of modern society in order to ensure sculpture’s relevance and cultural authority. We will examine the fate of the figurative tradition in the work of such sculptors as Carpeaux, Rodin, Leighton, Hildebrand, Degas, Claudel, and Vigeland. In turn, we will evaluate these developments in relation to the emergence of a self-conscious sculptural modernism in the work of such artists as Maillol, Matisse, Brancusi, Gaudier-Brzeska, and Picasso. In addition to a history of three-dimensional representation in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, this course will also introduce the critical vocabularies used to evaluate sculpture and its history. s t r u c t u r e o f t h e c o u r s e Each hour session will consist of lectures and discussions of images, texts, and course themes. -

Mors Janua Vitae’

Eliza Macloghlin and Alfred Gilbert’s ‘Mors janua vitae’ by KEREN HAMMERSCHLAG for the purpose of this article, the story of Eliza Macloghlin archives of the Royal College of Surgeons and the Royal Acad- starts with the death of her husband in 1904. We know very emy of Arts concerning one of Gilbert’s most significant yet little about Dr Edward Percy Macloghlin, aside from that he perplexing works. was the son of a surgeon and that he passed through Universi- Mors janua vitae (translated as ‘Death, the Gateway of Life’ or ty College, Liverpool, winning the Bligh gold medal in anat- ‘Death, the Gateway of Eternal Life’) started as a plaster mod- omy in 1882 and afterwards settling in Wigan. According to his el that was exhibited at the Summer Exhibition of the Royal obituary in the Wigan Observer, ‘For some time he had been out Academy in 1907 (Fig.29). According to the artist, the work of health, and his death at the comparatively early age of 45 is was intended to be exhibited ‘without identity’, ‘merely as a sincerely regretted. Dr. Macloghlin leaves a widow, a daughter subject illustration in portraiture’. Macloghlin, however, di- of Mr. Millard, of Wigan’.1 vulged the identity of the sitters to a mutual friend, the art For most Victorian and Edwardian women of the middle and critic Marion Harry Spielmann, prompting Gilbert to write to upper classes ‘widowhood was a final destiny, an involuntary Spielmann pleading that he not make the information public.4 commitment to a form of social exile’.2 For Eliza Macloghlin The plaster model was given by Eliza, at Gilbert’s original sug- (1863–1928), however, the death of her husband inspired a burst gestion, to the Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, and a reproduc- of creative energy. -

Bertram Mackennal and the Sculptural Femme Fatale in the 1890S

Circe 1893 (detail) bronze 240 x 79.4 x 93.4 cm National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne The Felton Bequest 1910 ‘Her invitation and her contempt’: Bertram Mackennal and the sculptural femme fatale in the 1890s DAVID J GETSY In the early 1890s Bertram Mackennal still struggled to find audiences, patrons and critical recognition. After having moved between Melbourne, London and Paris, he had been unsuccessful in garnering what he considered sufficient attention, and his letters from the period are fraught with anxieties and plans for his career. In 1892 he began working on a major life-size ‘statue’ in the ‘ideal’ or ‘imaginative’ genre that would, he hoped, establish his name. ‘I am trying to make a big work of this figure and at present am full of hope,’ he remarked.1 Such a gambit was common enough for an aspiring sculptor in the competitive market of the late 19th century. British sculpture, in particular, had been reinvigorated in the 1880s by artists who staked their reputations on similar highly-conceptualised life-size statues. This movement to modernise the theory and practice of sculpture in Britain would be dubbed the ‘New Sculpture’ in 1894 – the same year Mackennal’s own contribution to it could be seen at the Royal Academy of Art’s summer exhibition.2 As Mackennal knew himself from his brief time at the Royal Academy schools and from the contacts he made there, polemical statues such as his could be the statements through which debates about the theory, practice and future of sculpture occurred.3 Even after his move to Paris, Mackennal seems to have identified with these formulations of modern sculpture in London and kept a close eye on the British capital and the better market possibilities it offered for an Australian sculptor.4 His ambitious life-size statue, although first exhibited at the 1893 Paris Salon, drew deeply on his familiarity and sympathy with the aims of the New Sculpture, and it was in London where it made its more lasting impact. -

The Arts and Crafts Movement, Modernism, and Sculpture in Britain 1890–1914

Sarah Victoria Turner “Reuniting What Never Should Have Been Separated”: The Arts and Crafts Movement, Modernism, and Sculpture in Britain 1890–1914 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 2 (Summer 2015) Citation: Sarah Victoria Turner, “‘Reuniting What Never Should Have Been Separated’: The Arts and Crafts Movement, Modernism, and Sculpture in Britain 1890–1914,” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 2 (Summer 2015), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/ summer15/turner-on-the-arts-and-crafts-movement-modernism-and-sculpture-in-britain. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Turner: The Arts and Crafts Movement, Modernism, and Sculpture in Britain 1890–1914 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 14, no. 2 (Summer 2015) “Reuniting What Never Should Have Been Separated”: The Arts and Crafts Movement, Modernism, and Sculpture in Britain 1890–1914 by Sarah Victoria Turner The bonds between Modernist sculpture, the New Sculpture and the Arts and Crafts Movement . helped critics and the public to understand the products and claims of avant-garde sculptors before the First World War. —S. K. Tillyard[1] Chronologies of Sculpture “on or about” 1890 to 1914[2] In 1987, the writer and historian Stella Tillyard proffered an argument in her book The Impact of Modernism that went against the grain of most conceptualizations of British sculpture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth -

Queen Victoria Memorials in New Zealand Mark Stocker

‘A token of their love’: Queen Victoria Memorials in New Zealand Mark Stocker New Zealand makes a particularly apposite case study as the sole colonial focus in this issue of 19, although this writer must declare a certain bias. As not just part of the British world but in its self-image a ‘Better Britain’,1 late-colonial New Zealand honoured its first head of state in the form of the Queen Victoria public memorials erected in its four major metropoli- tan centres: Auckland, Christchurch, Dunedin, and Wellington. With New Zealand’s population of 815,862 in the 1901 census, Victoria was thus over twice as visible to her subjects as she was in the United Kingdom, indeed enjoying a more prominent profile than anywhere else in the British Empire apart from the Bahamas, Malta, and Mauritius, which were all far smaller colonies.2 Her memorials were erected, as the quotation in the title of this article suggests, as tokens of colonial love and loyalty. To some visi- tors, such a relationship appeared comically enduring. In 1978 Bob Hope quipped: ‘New Zealand is the only country where “God Save the Queen” is a love song.’3 Yet any study of the memorials reveals that a keen sense of local politics coexisted, often symbiotically, with the global, in a kind of imperial ‘cementing’ evident in their iconographic content, as well as what was said at the time of their erection. With the fascinating exception of the Queen Victoria at Ohinemutu, near Rotorua, colonial eyes were set on British sculptors as the sole providers of worthy memorials to her.