The Incredible Shrinking Man in Paul Auster's Report from The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study on the Two Turkısh Translatıons of Paul Auster's Cıty Of

Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 A CASE STUDY ON THE TWO TURKISH TRANSLATIONS OF PAUL AUSTER’S CITY OF GLASS İpek HÜYÜKLÜ Hacettepe University Graduate School of Social Sciences Department of Translation and Interpretation Master’s Thesis Ankara, 2015 iii ÖZET HÜYÜKLÜ, İpek. Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent adlı Eserinin İki Çevirisi üzerine bir Çalışma. Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Ankara, 2015. Bu çalışmanın amacı, Paul Auster’ın Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde çevirmene zorluk yaratacak öğelerin çevirmenler tarafından nasıl çevrildiğini Venuti’nin yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma kavramları ışığı altında analiz ederek çevirmenlerin uyguladıkları stratejileri tespit etmektir. Bunun yanı sıra Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünürlüğü ve görünmezliği yaklaşımları temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu ortaya koymak amaçlanmıştır. Bu amaç doğrultusunda, çevirmenler için zorluk yaratan öğelerin sıklıkla kullanıldığı ve postmodern biçemiyle bilinen Paul Auster’a ait Cam Kent adlı eserin Yusuf Eradam (1993) ve İlknur Özdemir (2004) tarafından Türkçe’ye yapılan iki farklı çevirisi analiz edilmiştir. Bu eserin çevirisini zorlaştıran faktörler; özel isimler, kelime oyunları, bireydil, dilbilgisel normlar, tipografi, gönderme ve yabancı sözcükler olmak üzere yedi başlık altında toplanmış olup Cam Kent romanının iki farklı çevirisinde tercih edilen çeviri stratejileri karşılaştırılmıştır. Bu karşılaştırma, Venuti’nin çevirmenin görünmezliği yaklaşımı temel alınarak hangi çevirmenin daha görünür ya da görünmez olduğunu incelemek üzere yapılmıştır. İki çevirinin karşılaştırmalı analizinin ardından, iki çevirmenin de farklı öğeler için yerlileştirme ve yabancılaştırma yaklaşımlarını bir çeviri stratejisi olarak kullandığı sonucuna varılmıştır. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 289 5th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2018) A Review of Paul Auster Studies* Long Shi Qingwei Zhu College of Foreign Language College of Foreign Language Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan, China Pingdingshan, China Abstract—Paul Benjamin Auster is a famous contemporary Médaille Grand Vermeil de la Ville de Paris in 2010, American writer. His works have won recognition from all IMPAC Award Longlist for Man in the Dark in 2010, over the world. So far, the Critical Community contributes IMPAC Award long list for Invisible in 2011, IMPAC different criticism to his works from varied perspectives in the Award long list for Sunset Park in 2012, NYC Literary West and China. This paper tries to make a review of Paul Honors for Fiction in 2012. Auster studies, pointing out the achievement which has been made and others need to be made. II. A REVIEW OF PAUL AUSTER‘S LITERARY CREATION Keywords—a review; Paul Auster; studies In 1982, Paul Auster published The Invention of Solitude which reflected a literary mind that was to be reckoned with. I. INTRODUCTION It consists of two sections. Portrait of an Invisible Man, the first part, is mainly about his childhood in which there is an Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is a absence of fatherly love and care. His memory of his growth talented contemporary American writer with great is full of lack of fatherly attention: ―for the first years of my abundance of voluminous works. -

An Analysis Of" City of Glass" by Paul Auster in Terms of Postmodernism

International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching Volume 5, Issue 1, April 2017, p. 478-486 Received Reviewed Published Doi Number 17.01.2017 16.02.2017 24.04.2017 10.18298/ijlet.1659 AN ANALYSIS OF CITY OF GLASS BY PAUL AUSTER FROM A POSTMODERNIST PERSPECTIVE1 Mehmet Cem ODACIOĞLU 2 & Chek Kim LOI3 & Fadime ÇOBAN4 ABSTRACT This study analyzes City of Glass, a postmodernist detective novella (or anti-detective) of the New York Trilogy by Paul Auster in terms of postmodernist elements and techniques such as metafiction, parody, intertextuality, irony. In doing so, some information about Auster’s life and the plot of the work are also offered to the reader to make the analysis more concrete. Last but not least, this study is also thought to be useful for students enrolled in English Language and Literary Departments for them to understand the movement of postmodernism. Key Words: City of Class, postmodernist detective fiction, anti-detective, metafiction, parody, irony, intertextuality, pastiche. 1.Short Biography of Paul Auster Paul Auster is an American-Jewish essayist, novelist, translator, poet, screenwriter and memoirist, who was born in Newark, New Jersey on February 3, 1947. Auster lived in a middle class family and spent some of his childhood in the Newark suburbs of South Orange and Maplewood. However, in 1959, his family moved into a large Tudor house. Auster's uncle, Allen Mandelbaum was a translator and left his books for him to read there when he decided to make a journey to Europe. Auster read all of these books which encouraged him to be interested in writing and in literature. -

Logic Intertextuality in the Works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Reading to you, or the aesthetics of marriage : dia- logic intertextuality in the works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40315/ Version: Full Version Citation: Williamson, Alexander (2018) Reading to you, or the aesthet- ics of marriage : dialogic intertextuality in the works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email 1 Reading to You, or the Aesthetics of Marriage Dialogic Intertextuality in the Works of Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster Alexander Williamson Doctoral thesis submitted in partial completion of a PhD at Birkbeck, University of London July 2017 2 Abstract Using a methodological framework which develops Vera John-Steiner’s identification of a ‘generative dialogue’ within collaborative partnerships, this research offers a new perspective on the bi-directional flow of influence and support between the married authors Siri Hustvedt and Paul Auster. Foregrounding the intertwining of Hustvedt and Auster’s emotional relationship with the embodied process of aesthetic expression, the first chapter traces the development of the authors’ nascent identities through their non-fictional works, focusing upon the autobiographical, genealogical, canonical and interpersonal foundation of formative selfhood. Chapter two examines the influence of postmodernist theory and poststructuralist discourse in shaping Hustvedt and Auster’s early fictional narratives, offering an alternative reading of Auster’s work outside the dominant postmodernist label, and attempting to situate the hybrid spatiality of Hustvedt and Auster’s writing within the ‘after postmodernism’ period. -

Critics on White Noise and Moon Palace. on Classification and Genre

Universiteit Utrecht MA – Westerse Literatuur en Cultuur: English Sarah Scholliers (3104591) Critics on White Noise and Moon Palace. On Classification and Genre Hans Bertens Onno Kosters July 2007 Table of Contents Introduction: On Classification 1 CHAPTER ONE: Genre(s) and Critics 4 Contemporary Criticism with Regard to Genre 5 Genres, Auster and DeLillo 9 Two Stories 10 Playing with Genres? 11 Moon Palace 11 White Noise 13 Conclusion 14 CHAPTER TWO: French Influences? 16 Derrida and the Instability of Language 17 Derridean Language in Auster and DeLillo 18 Lacan’s Theory of Language and the Unconscious: in Search of the Sublime 19 Lyotard and the Unpresentable 21 Auster’s and DeLillo’s Sublime: Echoes of Lacan and Lyotard, and Derridean examples 23 Baudrillard’s Simulation 27 A Baudrillardean Auster and DeLillo? 28 Conclusion 30 CHAPTER THREE: American Approaches 32 Postmodern Sublime 32 The Romantic Sublime 32 Space 32 Magic and Dread – The Question of Language 35 Systems Theory 39 Conclusion 42 General Conclusion 43 Bibliography 46 I would like to thank Professor Hans Bertens and Dr. Onno Kosters, my supervisor and co-supervisor respectively, for the careful reading of the first versions of my thesis. INTRODUCTION On Classification Most people have clear ideas about the nature of a work of art. They tend to classify it within a particular category with which they are familiar. They do so, based on their own experience with this (and other) artwork, on critics’ opinion, popular media or hearsay. In general, people approach works of art with an unambiguous view, and they classify a film as a comedy or a book as a thriller. -

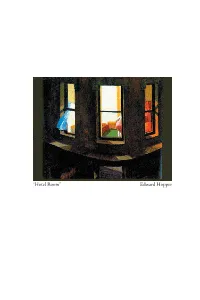

Edward Hopper the Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster

“Hotel Room” Edward Hopper The Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster James Peacock University of Edinburgh Auster contributed an extract from Moon Palace to the collection “Edward Hopper and the American Imagination,” and it is clear that Hopper’s images of alienated individuals have had a profound resonance for him. This paper employs two main ideas to compare them. First, a pivotal moment in American literature: the hotel room drama watched by Coverdale in Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance. Secondly, Aby Warburg’s concept of the “pathos formula” in art, which bypasses the problematic issue of influence, choosing instead to posit sets of inherited cultural memories. It therefore allows discussion of the re-emergence of Hawthorne’s puritan tropes of paranoid specularity and transcendence in the work of Hopper and Auster. I was never able to paint what I set out to paint. (Edward Hopper, quoted in O’Doherty 77) Words are transparent for him, great windows that stand between him and the world, and until now they have never impeded his view, have never even seemed to be there. (G 146) Somewhere in New England in the nineteenth century, a man resumes his “post” (Hawthorne 168) at his hotel room window, there to observe the boarding house opposite. Before long, a “knot of characters” enters one of the rooms, appearing before our observer as if projected onto the physi- cal stage, having been “kept so long upon my mental stage, as actors in a drama.” Longing for “a catastrophe,” some moment of high theatre to fill the epistemological void of his own soul, our voyeur gazes with increasing intensity, fabricating scenarios which, he admits, “might have been alto- gether the result of fancy and prejudice in me.” When, in one of the most compelling and influential moments in all American literature, he is spot- ted by the female protagonist and barred from the scene by the dropping of a curtain, his appetite for narrative resolution remains unsated and he is condemned to brood on his isolation once more. -

“Then Catastrophe Strikes:” Reading Disaster in Paul Auster's Novels and Autobiographies « Then Catastrophe Strikes

Université Paris-Est Northwestern University École doctorale CS – Cultures et Sociétés Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences Laboratoire d’accueil : IMAGER Institut des Comparative Literary Studies Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman, EA 3958 “T HEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES :” READING DISASTER IN PAUL AUSTER ’S NOVELS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES « THEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES » : LIRE LE DÉSASTRE DANS L’ŒUVRE ROMANESQUE ET AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUE DE PAUL AUSTER Thèse en cotutelle présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Paris- Est, et de Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature de Northwestern University, par Priyanka DESHMUKH Sous la direction de Mme le Professeur Isabelle ALFANDARY et de M. le Professeur Samuel WEBER Jury Mme Isabelle ALFANDARY , Professeur à l’Université Paris-3 Sorbonne Nouvelle (Directrice de thèse) Mme Sylvie BAUER , Professeur à l’Université Rennes-2 (Rapporteur) Mme Christine FROULA , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) Mme Michal GINSBURG , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) M. Jean-Paul ROCCHI , Professeur à l’Université Paris-Est (Examinateur) Mme Sophie VALLAS , Professeur à l’Université d’Aix-Marseille (Rapporteur) M. Samuel WEBER , Professeur à Northwestern University (Co-directeur de thèse) In memory of Matt Acknowledgements I wish I had a more gracious thank-you for: Mme Isabelle Alfandary , who, over the years has allowed me to experience untold academic privileges; whose constant and consistently nurturing presence, intellectual rigor, patience, enthusiasm and invaluable advice are the sine qua non of my growth and, as a consequence, of this work. M. Samuel Weber , whose intellectual generosity, patience and understanding are unparalleled, whose Paris Program in Critical Theory was critical in more ways than one, and without whose participation, the co-tutelle would have been impossible. -

Download the Story of My Typewriter, Paul Auster, Sam Messer, D.A.P

The story of my typewriter, Paul Auster, Sam Messer, D.A.P., 2002, 1891024329, 9781891024320, 63 pages. This is the story of Paul Auster's typewriter. The typewriter is a manual Olympia, more than 25 years old, and has been the agent of transmission for the novels, stories, collaborations, and other writings Auster has produced since the 1970s, a body of work that stands as one of the most varied, creative, and critcally acclaimed in recent American letters. It is also the story of a relationship. A relationship between Auster, his typewriter, and the artist Sam Messer, who, as Auster writes, "has turned an inanimate object into a being with a personality and a presence in the world." This is also a collaboration: Auster's story of his typewriter, and of Messer's welcome, though somewhat unsettling, intervention into that story, illustrated with Messer's muscular, obsessive drawings and paintings of both author and machine. This is, finally, a beautiful object; one that will be irresistible to lovers of Auster's writing, Messer's painting, and fine books in general.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1bs6nlL Hand to Mouth A Chronicle of Early Failure, Paul Auster, Aug 1, 2003, Biography & Autobiography, 169 pages. From the streets of Manhattan to Paris, a poignant memoir explains a series of ingenious and farfetched attempts to survive on next to no money, showing both the humor and .... Office Collectibles 100 Years of Business Technology, Thomas A. Russo, Jun 1, 2000, , 224 pages. This book presents the most comprehensive collection of antique and collectible office technology that has appeared to date. -

In Search of Self: Explorations of Identity in the Work of Paul Auster

In Search of Self: Explorations of Identity in the Work of Paul Auster THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa by Andrew Edward van der Vlies 1998 II ABSTRACT Paul Auster is regarded by some as an important novelist. He has, in a relatively short space of time, produced an intriguing body of work, which has attracted comparatively little critical attention. This study is based on the premise that Auster's art is the record of an entertaining, intelligent and utterly serious engagement with the possibilities of conceiving of the identity of an individual subject in the contemporary, late-twentieth century moment. This study, focussing on Auster's novels, but also considering selected poetry and critical prose, explores the representation of identity in his work. The short Foreword introduces Paul Auster and sketches in outline the concerns of the study. Chapter One explores the manner in which Auster's early (anti-),detective' fiction develops a concern with identity. It is suggested that Squeeze Play, Auster's pseudonymous 'hard-boiled' detective thriller, provided the author with a testing ground for his subsequent appropriation and subversion of the detective genre in The New York Trilogy. Through a close consideration of City of Glass, and an examination of elements in Ghosts, it is shown how the loss of the traditional detective's immunity, and the problematising of strategies which had previously guaranteed him access to interpretive and narrative closure, precipitates a collapse which initiates an interrogation of the nature and construction of ideas about individual identity. -

Blue Gum 2 Complete

Blue Gum, No. 2, 2015, ISSN 2014-21-53, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians, Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona A Glimpse at Paul Auster and Jorge L. Borges through the Tinted Glass of Quantum Theory Myriam M. Mercader Varela Copyright©2015 Myriam M. Mercader Varela. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged. Abstract . The works of Jorge Luis Borges and Paul Auster seem to follow the rules of Quantum Theory. The present article studies a number of perspectives and coincidences in their oeuvre, especially a quality we have named “inherent ubiquity” which highlights the importance and of authorship and identity and the appearance of blue stones to mark the doors leading to new dimensions on the works of both authors. Keywords: Jorge L. Borges, Paul Auster, Authorship and Identity, Quantum Theory, Inherent Ubiquity, Blue Stones. Quantum Theory has ruled the scientific milieu for decades now, but it is not only for science that Quantum Theory makes sense. Literary critics have surrendered to its logic as a unique way to interpret literature because the world we live and write in is one and the same; it forms part of a whole. Although this article does not aim to analyze Quantum Theory, we would like to make a short summary of its basis in order to shape the arena we are stepping into. In 1982 a famous experiment undertaken by Alain Aspect proved that a very large percentage of the polarization angles of photons emitted by a laser beam was identical, which meant that particles necessarily communicate their position so that each photon’s orientation can parallel that of the one that serves as its pair. -

The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster's White Spaces and Winter Journal

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 2 | 2016 New Approaches to the Body The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal François Hugonnier Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/1801 DOI: 10.4000/angles.1801 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference François Hugonnier, « The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal », Angles [Online], 2 | 2016, Online since 01 April 2016, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/1801 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/angles.1801 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal 1 The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal François Hugonnier “If it really has to be said, it will create its own form.” Paul Auster (1995: 104) 1 White Spaces is a short matrix text written by the poet, novelist and film-maker Paul Auster in the winter of 1978-1979. This meditation on the body, on silence, language and narration is Auster’s immediate reaction to his “epiphanic moment of clarity” (2012: 220, original emphasis) which happened during a dance rehearsal in New York. Initially entitled “Happiness, or a Journey through Space” and “A Dance for Reading Aloud”,1 this hybrid piece of poetic prose was retrospectively considered as “the bridge between writing poetry and writing prose” (1995: 132), and “the bridge to everything you have written in the years since then” (2012: 224). -

Kvarterakademisk

kvarter Volume 07 • 2013 akademiskacademic quarter Fieldwork Paul Auster as a Popular Postmodern Fiction Writer Bent Sørensen Ph.D., Associate Professor of English at the Dept. of Culture and Global Studies, AAU, and President of PSY-ART, the Foundation for the Psychological Study of the Arts. He has published extensively on Beat Generation writers and postmodern American fiction and culture. Abstract This article examines some aspects of the phenomenon of popular fiction, using the terminology proposed by Pierre Bourdieu in his works on distinction and cultural production, including ‘position taking,’ ‘field,’ and ‘capital(s).’ After the theoretical groundwork is laid, the second half of the article analyzes specifically the case of popular postmodern author Paul Auster, with regards to the role of genre and dual readership/reading protocol inscribed in his fic- tions, the mechanisms of gatekeeping, consecration and position taking involved in the production of his place in the field of popu- lar fiction (cf. Ken Gelder’s Popular Fiction: The Logics and Practices of a Literary Field, 2004),1 and the distinct American and European/ Scandinavian markets for his books. Keywords Paul Auster, Pierre Bourdieu, fieldwork, position taking, capital, consecration. Bourdieu’s fieldwork Pierre Bourdieu’s extensive work in literary sociology forms the starting point of this inquiry. Bourdieu was never explicitly inter- Volume 07 66 Fieldwork kvarter Bent Sørensen akademiskacademic quarter ested in the popular forms of culture, but his theories concerning agency and taste formation in high culture lend themselves excel- lently to use also on popular culture phenomena. A very compact quote from Bourdieu’s The Field of Cultural Production (1993) below must first be unpacked and operationalized: The task is that of constructing the space of positions and the space of the position takings (prises de position) in which they are expressed.