An Oral History of a Pit Village

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Printed at 14:21 on 31/01/19 Appeals to Be Heard by the Local Valuation

Printed at 14:21 on 31/01/19 Appeals to be Heard by the Local Valuation Panel Date of Hearing : 16/04/19 Page 1 Location :THE ABBOTSFORD HOTEL, STIRLING ROAD, DUMBARTON, G82 2PJ Description / Appellant / Appeal Appealed Valuer dealing with appeal Property Reference Situation Agent Flag Value _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 02/01/H38670/0009B DAY NURSERY WEST DUNBARTONSHIRE COUNCIL AP1A 6,300 James Boyle 9B ROSS LOAN EDUCATION & CULTURAL SERVICES 0141 562 1278 GARTOCHARN ASSET MANAGEMENT SECTION [email protected] ALEXANDRIA WEST DUNBARTONSHIRE COUNCIL G83 8NE 6-14 BRIDGE STREET (SECOND FLOOR) DUMBARTON G82 1NT ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 02/02/H18660/0003 WORKSHOP ETC FirstGroup plc AT1A 100,500 Jennifer MacLachlan BIRCH ROAD GVA GRIMLEY 0141 562 1235 DUMBARTON SUTHERLAND HOUSE [email protected] G82 2RF 149 ST VINCENT STREET GLASGOW G2 5NW ________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ 02/02/H18660/0005 FACTORY AGGREKO UK LTD AP1A 171,500 Jennifer MacLachlan 5 BIRCH ROAD Wymre 0141 562 1235 DUMBARTON c/o WYM Rating, [email protected] -

Early Learning and Childcare Funded Providers 2019/20

Early Learning and Childcare Funded Providers 2019/20 LOCAL AUTHORITY NURSERIES NORTH Abronhill Primary Nursery Class Medlar Road Jane Stocks 01236 794870 [email protected] Abronhill Cumbernauld G67 3AJ Auchinloch Nursery Class Forth Avenue Andrew Brown 01236 794824 [email protected] Auchinloch Kirkintilloch G66 5DU Baird Memorial PS SEN N/Class Avonhead Road Gillian Wylie 01236 632096 [email protected] Condorrat Cumbernauld G67 4RA Balmalloch Nursery Class Kingsway Ruth McCarthy 01236 632058 [email protected] Kilsyth G65 9UJ Carbrain Nursery Class Millcroft Road Acting Diane Osborne 01236 794834 [email protected] Carbrain Cumbernauld G67 2LD Chapelgreen Nursery Class Mill Road Siobhan McLeod 01236 794836 [email protected] Queenzieburn Kilsyth G65 9EF Condorrat Primary Nursery Class Morar Drive Julie Ann Price 01236 794826 [email protected] Condorrat Cumbernauld G67 4LA Eastfield Primary School Nursery 23 Cairntoul Court Lesley McPhee 01236 632106 [email protected] Class Cumbernauld G69 9JR Glenmanor Nursery Class Glenmanor Avenue Sharon McIlroy 01236 632056 [email protected] Moodiesburn G69 0JA Holy Cross Primary School Nursery Constarry Road Marie Rose Murphy 01236 632124 [email protected] Class Croy Kilsyth G65 9JG Our Lady and St Josephs Primary South Mednox Street Ellen Turnbull 01236 632130 [email protected] School Nursery Class Glenboig ML5 2RU St Andrews Nursery Class Eastfield Road Marie Claire Fiddler -

The Antonine Wall, the Roman Frontier in Scotland, Was the Most and Northerly Frontier of the Roman Empire for a Generation from AD 142

Breeze The Antonine Wall, the Roman frontier in Scotland, was the most and northerly frontier of the Roman Empire for a generation from AD 142. Hanson It is a World Heritage Site and Scotland’s largest ancient monument. The Antonine Wall Today, it cuts across the densely populated central belt between Forth (eds) and Clyde. In The Antonine Wall: Papers in Honour of Professor Lawrence Keppie, Papers in honour of nearly 40 archaeologists, historians and heritage managers present their researches on the Antonine Wall in recognition of the work Professor Lawrence Keppie of Lawrence Keppie, formerly Professor of Roman History and Wall Antonine The Archaeology at the Hunterian Museum, Glasgow University, who spent edited by much of his academic career recording and studying the Wall. The 32 papers cover a wide variety of aspects, embracing the environmental and prehistoric background to the Wall, its structure, planning and David J. Breeze and William S. Hanson construction, military deployment on its line, associated artefacts and inscriptions, the logistics of its supply, as well as new insights into the study of its history. Due attention is paid to the people of the Wall, not just the ofcers and soldiers, but their womenfolk and children. Important aspects of the book are new developments in the recording, interpretation and presentation of the Antonine Wall to today’s visitors. Considerable use is also made of modern scientifc techniques, from pollen, soil and spectrographic analysis to geophysical survey and airborne laser scanning. In short, the papers embody present- day cutting edge research on, and summarise the most up-to-date understanding of, Rome’s shortest-lived frontier. -

Local Landscape Character Assessment Background Report

NORTH LANARKSHIRE LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN MODIFIED PROPOSED PLAN LOCAL LANDSCAPE CHARACTER ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND REPORT NOVEMBER 2018 North Lanarkshire Council Enterprise and Communities CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 3. Kilsyth Hills Special Landscape Area (SLA) 4. Clyde Valley Special Landscape Area (SLA) Appendices Appendix 1 - URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 1. Introduction 1.1 Landscape designations play an important role in Scottish Planning Policy by protecting and enhancing areas of particular value. Scottish Planning Policy encourages local, non-statutory designations to protect and create an understanding of the role of locally important landscape have on communities. 1.2 In 2014, as part of the preparation of the North Lanarkshire Local Development Proposed Plan, a review of local landscape designations was undertaken by URS as part of wider action for landscape protection and management. 2. URS Review of North Lanarkshire Local Landscape Character (2015) 2.1 The purpose of the Review was to identify and provide an awareness of the special character and qualities of the designated landscape in North Lanarkshire and to contribute to guiding appropriate future development to the most appropriate locations. The Review has identified a number of Local Landscape Units (LLU) that are of notable quality and value within which future development requires careful consideration to avoid potential significant impact on their landscape character. 2.2 There are two exemplar LLUs identified in this study, Kilsyth Hills and Clyde Valley, which are seen as very sensitive to development. Both of these areas warrant specific recognition and protection, as their high landscape quality would be threatened and adversely affected by unsympathetic development within their boundaries. -

Greater Glasgow & the Clyde Valley

What to See & Do 2013-14 Explore: Greater Glasgow & The Clyde Valley Mòr-roinn Ghlaschu & Gleann Chluaidh Stylish City Inspiring Attractions Discover Mackintosh www.visitscotland.com/glasgow Welcome to... Greater Glasgow & The Clyde Valley Mòr-roinn Ghlaschu & Gleann Chluaidh 01 06 08 12 Disclaimer VisitScotland has published this guide in good faith to reflect information submitted to it by the proprietor/managers of the premises listed who have paid for their entries to be included. Although VisitScotland has taken reasonable steps to confirm the information contained in the guide at the time of going to press, it cannot guarantee that the information published is and remains accurate. Accordingly, VisitScotland recommends that all information is checked with the proprietor/manager of the business to ensure that the facilities, cost and all other aspects of the premises are satisfactory. VisitScotland accepts no responsibility for any error or misrepresentation contained in the guide and excludes all liability for loss or damage caused by any reliance placed on the information contained in the guide. VisitScotland also cannot accept any liability for loss caused by the bankruptcy, or liquidation, or insolvency, or cessation of trade of any company, firm or individual contained in this guide. Quality Assurance awards are correct as of December 2012. Rodin’s “The Thinker” For information on accommodation and things to see and do, go to www.visitscotland.com at the Burrell Collection www.visitscotland.com/glasgow Contents 02 Glasgow: Scotland with style 04 Beyond the city 06 Charles Rennie Mackintosh 08 The natural side 10 Explore more 12 Where legends come to life 14 VisitScotland Information Centres 15 Quality Assurance 02 16 Practical information 17 How to read the listings Discover a region that offers exciting possibilities 17 Great days out – Places to Visit 34 Shopping every day. -

Roman Inscriptions from Scotland: Some Additions and Corrections to RIB I L J F Keppie*

Proc Antigc So Scot, (1983)3 11 , 391-404 Roman inscriptions from Scotland: some additions and corrections to RIB I L J F Keppie* Nearl year0 y2 s have elapsed sinc completioe th e WrighP R firse f wory th o tn tb n ko volum Romane Th f eo Inscriptions f Britain,o which provide detaileda d descriptio drawd nan - more in f eacth go f eho than 2000 inscribed stones foun Britai n di 195o t p 4nu (Collingwoo d & Wright 1965). Of these about 125 derived from Scotland. Since then a further 19 stones (some complete, others fragmentary) have come to light within Scotland's modern political boundaries. Most have already received definitiv t leasa r eto preliminary publicatio varieta n i y of journals, but it may be of use, since the appearance of supplements to RIB remains a distant prospect havo t , e these collecte singla n i d e place additionn I . numbea , f improveo r d read- ings to published inscriptions have followed upon the cleaning of stones in the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland, Edinburgh (hereafter NMAS), and the Hunterian Museum, Universit f Glasgoyo w (hereafter HM) preparation i , re-displayr nfo mord an , e recently during preparatory work for the Scottish Fascicule of the Corpus of Roman Sculpture (Keppie & Arnold 1984). The following report is divided into three sections: I, improvements to the readings of inscriptions already publishe RIB;description da i , II stonef no s lont g helbu , NMAy db HM r So only recently perceive inscribede b o dt ; III resumdiscoveriea ,w ne f eo s made since 1954. -

Antonine Wall - Dullatur

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC172 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90017); Taken into State care: 1960 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2018 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ANTONINE WALL - DULLATUR We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office:Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ANTONINE WALL - DULLATUR BRIEF DESCRIPTION The property is part of the Antonine Wall and comprises a 550m long stretch of ditch, upcast bank and Military Way (the latter not visible). It is set on a south- sloping hill on the fringes of a golf course and lies between the Roman forts of Croy (2km to the west) and Westerwood (500m to the east) The Antonine Wall is a linear Roman frontier system of wall and ditch accompanied at stages by forts and fortlets, linked by a road system termed the Military Way, stretching 60km from Bo’ness on the Forth to Old Kilpatrick on the Clyde. It is one of only three linear barriers along the 2000km European frontier of the Roman Empire. These systems are unique to Britain and Germany. CHARACTER OF THE MONUMENT Historical Overview • Antonine Wall construction initiated by Emperor Antoninus Pius (AD 138– 161) after a successful campaign in AD 139/142 by the Governor of Britain, Lollius Urbicus • This section of Antonine Wall built by legio XX Valeria Victrix. -

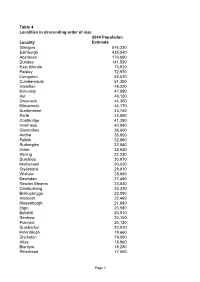

Table 4 Localities in Descending Order of Size Locality 2004 Population

Table 4 Localities in descending order of size 2004 Population Locality Estimate Glasgow 575,330 Edinburgh 435,540 Aberdeen 176,690 Dundee 141,590 East Kilbride 73,820 Paisley 72,970 Livingston 53,670 Cumbernauld 51,300 Hamilton 48,220 Kirkcaldy 47,090 Ayr 46,120 Greenock 44,300 Kilmarnock 44,170 Dunfermline 43,760 Perth 43,590 Coatbridge 41,280 Inverness 40,880 Glenrothes 38,600 Airdrie 35,850 Falkirk 32,890 Rutherglen 32,840 Irvine 32,620 Stirling 32,230 Dumfries 30,970 Motherwell 30,520 Clydebank 29,610 Wishaw 28,840 Bearsden 27,460 Newton Mearns 23,530 Cambuslang 23,320 Bishopbriggs 23,080 Arbroath 22,460 Musselburgh 21,880 Elgin 20,580 Bellshill 20,510 Renfrew 20,150 Polmont 20,130 Dumbarton 20,070 Kirkintilloch 19,660 Clarkston 19,000 Alloa 18,960 Blantyre 18,280 Peterhead 17,560 Page 1 Localities in descending order of size 2004 Population Locality Estimate Stenhousemuir 17,300 Grangemouth 17,280 Barrhead 17,250 Kilwinning 16,320 Giffnock 16,190 Buckhaven 16,140 Viewpark 15,780 Port Glasgow 15,760 Johnstone 15,710 Bathgate 15,650 Larkhall 15,560 Erskine 15,550 St Andrews 15,200 Prestwick 14,800 Troon 14,430 Helensburgh 14,410 Penicuik 14,320 Bonnyrigg 14,250 Bo'ness 14,240 Hawick 14,210 Galashiels 13,960 Broxburn 13,630 Carluke 13,590 Alexandria 13,480 Forfar 13,150 Linlithgow 13,130 Mayfield 12,910 Milngavie 12,820 Rosyth 12,490 Fraserburgh 12,150 Cowdenbeath 11,720 Gourock 11,690 Saltcoats 11,560 Largs 11,360 Dalkeith 11,260 Whitburn 10,830 Montrose 10,790 Inverurie 10,760 Ardrossan 10,720 Stranraer 10,600 Carnoustie 10,260 Stonehaven -

CONTACT LIST.Xlsx

Valuation Appeal Hearing: 6th November 2019 Contact list Property ID ST A Street Locality Description Appealed NAV Appealed RV Agent Name Appellant Name Contact Contact Number No. UNIT 25A 125 MAIN STREET COATBRIDGE PUBLIC HOUSE £75,500 £75,500 A.S.E.S GREGOR MCLEOD 01698 476059 UNIT 25A 125 MAIN STREET COATBRIDGE PUBLIC HOUSE £75,500 £75,500 A.S.E.S GREGOR MCLEOD 01698 476059 172 MAIN STREET BELLSHILL SHOP £7,000 £7,000 AL MORTGAGES LTD CHRISTINE MAXWELL 01698 476053 Yard A, Banton Mill 43 A BANTON KILSYTH YARD £3,500 £3,500 BENNETT DEVELOPMENTS LTD CHRISTINE MAXWELL 01698 476053 BLOCK 14A (REAR) 80 INDUSTRIAL ESTATE NEWHOUSE FACTORY £61,500 £61,500 EURO-FAB (SCOTLAND) LTD CHRISTINE MAXWELL 01698 476053 Hup Lee Buffet Restaurant 129 MERRY STREET MOTHERWELL LICENSED RESTAURANT £75,500 £75,500 FU LEE LIMITED ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 Unit 3 2 PARKLANDS AVENUE EUROCENTRAL LICENSED RESTAURANT £36,500 £36,500 HANMAC LIMITED ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 WOODSIDE BAR 2 MITCHELL STREET COATBRIDGE PUBLIC HOUSE £20,500 £20,500 HUGH MCCORMACK GREGOR MCLEOD 01698 476059 FRANKLYNS 16 HAMILTON ROAD BELLSHILL PUBLIC HOUSE £42,500 £42,500 JAMES HARE ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 1 TENNENT STREET COATBRIDGE SNACK BAR £17,700 £17,700 KIM STOKES ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 104 ORBISTON STREET MOTHERWELL OFFICE £14,300 £14,300 LIDL (UK) G M B H DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BOARS HEAD 1 BORE ROAD AIRDRIE PUBLIC HOUSE £20,250 £20,250 MARGARET DIVERS GREGOR MCLEOD 01698 476059 FRANKLYNS 16 HAMILTON ROAD BELLSHILL PUBLIC HOUSE £42,500 £42,500 MODA PROPERTIES LTD ROBERT KNOX -

The Antonine Wall: Rome's Final Frontier Teachers' Resource Pack

The Antonine Wall: Rome’s Final Frontier Teachers’ Resource Pack Compiled by Grace Hepworth, MSC Museum Studies, 2012 Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................... 2 About this pack ........................................................................................................................... 3 Curriculum for Excellence ............................................................................................................ 4 What to expect at the museum .................................................................................................. 6 Pre-visit discussion points ...................................................................................... 7 Visit activities ......................................................................................................... 9 Teacher-led tour ......................................................................................................................... 9 Worksheets ............................................................................................................................... 24 Supplementary worksheet ........................................................................................................ 31 Post-visit activities ............................................................................................... 33 Useful Online Resources ...................................................................................... 40 Suggested -

Recycling Waste

Recycling Waste Street Comments Town General Waste Grey Bin Blue/Brown Bins Food Waste Caddy Calendar Abbotsford Bishopbriggs Sunday Sunday Monday Calendar 1 Abbotsford Drive Kirkintilloch Wednesday Wednesday Wednesday Calendar 2 Abbotsford Road * 2 domestic uplifts a week Flats Bearsden Sunday/Thursday Abbotsford Road Bearsden Sunday Sunday Sunday Calendar 2 Abercrombie Drive Bearsden Tuesday Tuesday Sunday Calendar 1 Academy Gardens Lanes Vehicle Bearsden Thursday Saturday Monday Calendar 2 Achray Place Milngavie Saturday Saturday Friday Calendar 1 Acre Valley Road Farm & Country Torrance Thursday Wednesday Same day as refuse or reycling bin Calendar 1 Adamslie Crescent Kirkintilloch Friday Friday Sunday Calendar 1 Adamslie Drive Kirkintilloch Friday Friday Sunday Calendar 1 Afton Crescent Bearsden Thursday Thursday Friday Calendar 1 Afton View Farm & Country Kirkintilloch Monday Tuesday Sunday Calendar 1 Ailsa Drive Kirkintilloch Friday Friday Sunday Calendar 2 Ailsa Road Bishopbriggs Sunday Sunday Monday Calendar 1 Airlie Avenue Bearsden Monday Monday Monday Calendar 2 Albert Drive Bearsden Thursday Thursday Friday Calendar 1 Albert Road Lenzie Tuesday Tuesday Monday Calendar 2 Alder Avenue Lenzie Wednesday Wednesday Wednesday Calendar 2 Alder Road Milton of Campsie Sunday Sunday Sunday Calendar 1 Alexander Avenue Twechar Friday Friday Monday Calendar 2 Alexander Grove Bearsden Saturday Saturday Tuesday Calendar 1 Alexander Grove Flats Bearsden Saturday Saturday Alexander Place Waterside Saturday Saturday Monday Calendar 2 Alexandra -

CONTACT LIST.Xlsx

Valuation Appeal Hearing: 27th May 2020 Contact list Property ID ST A Street Locality Description Appealed NAV Appealed RV Agent Name Appellant Name Contact Contact Number No. 24 HILL STREET CALDERCRUIX SELF CATERING UNIT £1,400 £1,400 DEIRDRE ALLISON DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 56 WEST BENHAR ROAD HARTHILL HALL £18,000 £18,000 EASTFIELD COMMUNITY ACTION GROUP DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BUILDING 1 CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE WORKSHOP £44,000 £44,000 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BUILDING 2 CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE STORE £80,500 £80,500 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BLDG 4 PART CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE OFFICE £41,750 £41,750 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE OFFICE £24,000 £24,000 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 BUILDING 7 CENTRUM PARK 5 HAGMILL ROAD COATBRIDGE WORKSHOP £8,700 £8,700 FULMAR PROPERTIES LTD DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 1 GREENHILL COUNTRY ESTATE GREENHILL HOUSE GOLF DRIVING RANGE £5,400 £5,400 GREENHILL GOLF CO CHRISTINE MAXWELL 01698 476053 CLIFTONHILL SERVICE STN 231 MAIN STREET COATBRIDGE SERVICE STATION £41,000 £41,000 GROVE GARAGES INVESTMENTS LIMITED ROBERT KNOX 01698 476072 UNIT B3 1 REEMA ROAD BELLSHILL OFFICE £17,900 £17,900 IN-SITE PROPERTY SOLUTIONS LIMITED DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 UNIT B2 1 REEMA ROAD BELLSHILL OFFICE £18,600 £18,600 IN-SITE PROPERTY SOLUTIONS LIMITED DAVID MUNRO 01698 476054 2509 01 & 2509 02 42 CUMBERNAULD ROAD STEPPS ADVERTISING STATION £3,600 £3,600 J C DECAUX CHRISTINE MAXWELL