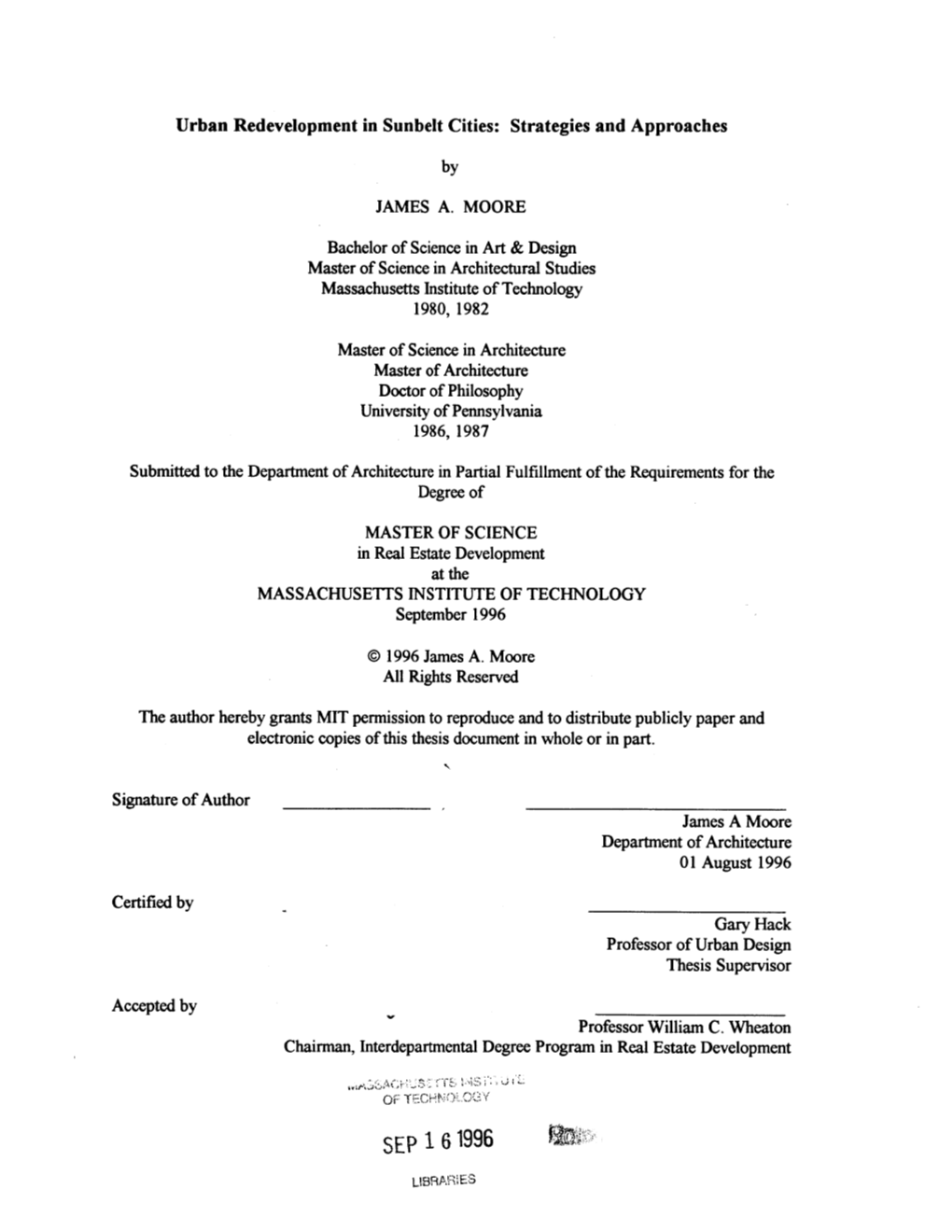

SEP 16 1996 Urban Redevelopment in Sunbelt Cities: Strategies and Approaches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Towards Trash Free Waters: Quantifying Potential Aquatic Trash Recovery in the Hillsborough River Watershed

Towards Trash Free Waters: Quantifying Potential Aquatic Trash Recovery in the Hillsborough River Watershed Prepared for Nestlé Waters North America October 27, 2015 Prepared by Timothy G. Townsend (Principal Investigator) Max J. Krause Sarah A. Gustitus Jeremy Toms University of Florida Gainesville, FL 32611 i Executive Summary Despite advances in solid waste management and increased awareness of the negative environmental consequences of pollution, littering is still common in the US. Littering can be the result of carelessness, accidents, or intentional actions, but the effect is the same. In recent years, concerned citizens have increased their attention to litter in the Hillsborough River Watershed (HRW). The University of Florida (UF) research team collaborated with local municipalities and non-government organizations (NGOs) to quantify and map the quantity of collected litter within the HRW. Because much of the storm water within the HRW drains into the Hillsborough River, all of the litter within the watershed has the potential to become aquatic trash (PAT). The PAT that was collected in roadside and park cleanups before it made its way into the Tampa Bay or the Gulf of Mexico (recovered PAT) was cataloged into a database and mapped using ESRI ArcGIS software. Concentrations of recovered PAT were reported as pounds per acre for 1,015 cleanup events at 168 unique sites within the HRW from 2008-2014, shown in Figure E1. Additionally, educational campaigns such as storm drain markings and field visits by the WaterVentures mobile lab were mapped to identify where residents could be expected to have increased awareness of the negative issues associated with littering. -

Ffifi** REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL Parm This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 RECEIVED 2280 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. 10-90 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JAN 1 9 2008 NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES NAl F EGlSTEROFh ffifi** REGISTRATION FORM NATIONAL PARm This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property_____________________________________________________ historic name ROBLES. HORACE T. HOUSE________________________________________ other names/site number Robles Family Home_______________________________________ 2. Location street & number 2604 East Hanna Avenue N/A D not for publication city or town Tampa ___N/A D vicinity state FLORIDA code FL county Hillsborough _code 057 zio code 33610 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this El nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property I3 meets O does not meet the National Register criteria. -

City of Tampa Walk–Bike Plan Phase VI West Tampa Multimodal Plan September 2018

City of Tampa Walk–Bike Plan Phase VI West Tampa Multimodal Plan September 2018 Completed For: In Cooperation with: Hillsborough County Metropolitan Planning Organization City of Tampa, Transportation Division 601 East Kennedy Boulevard, 18th Floor 306 East Jackson Street, 6th Floor East Tampa, FL 33601 Tampa, FL 33602 Task Authorization: TOA – 09 Prepared By: Tindale Oliver 1000 N Ashley Drive, Suite 400 Tampa, FL 33602 The preparation of this report has been financed in part through grants from the Federal Highway Administration and Federal Transit Administration, U.S. Department of Transportation, under the Metropolitan Planning Program, Section 104(f) of Title 23, U.S. Code. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the official views or policy of the U.S. Department of Transportation. The MPO does not discriminate in any of its programs or services. Public participation is solicited by the MPO without regard to race, color, national origin, sex, age, disability, family or religious status. Learn more about our commitment to nondiscrimination and diversity by contacting our Title VI/Nondiscrimination Coordinator, Johnny Wong at (813) 273‐3774 ext. 370 or [email protected]. WEST TAMPA MULTIMODAL PLAN Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction and Purpose ......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

![Greenways Trails [EL08] 20110406 Copy.Eps](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8169/greenways-trails-el08-20110406-copy-eps-718169.webp)

Greenways Trails [EL08] 20110406 Copy.Eps

R 17 E R 18 E R 19 E R 20 E R 21 E R 22 E MULTI-USE, PAVED TRAILS Suncoast NAME MILES Air Cargo Road 1.4 G HILLSBOROUGH Al Lopez Park 3.3 BrookerBrooker CreekCreek un n CorridorCorridor Suncoast H Aldermans Ford Park 1.9 w y Trail Amberly Drive 2.8 l B LakeLake DanDan 39 Bayshore Boulevard Greenways 4.4 EquestrianEquestrian TrailTrail Lake s GREENWAYS SYSTEM F z e n Lut rn R P d w OakridgeOakridge Brandon Parkway 1.4 o EquestrianEquestrian TrailTrail HillsboroughHillsborough RRiveriver LLUTZUTZ LAKEAKE FERNF D Bruce B Downs Boulevard 4.8 BrookerBrooker CCreekreek ERN RDRD StateState ParkPark B HeadwatersHeadwaters 75 NNewew TTampaampa Y e Cheney Park 0.3 TrailTrail c A LutzLutz W u Commerce Park Boulevard 1.4 KeystoneKeystone K Tam r BlackwaterBlackwater Bruce B Downs Bl Downs B Bruce R ew pa B A N N Bl FloridaFlorida TrailTrail PPARKWAY L reek CreekCreek PreservePreserve Compton Drive 1.4 C D TrailTrail Bl E E ss Copeland Park 2.3 D K CypressCypress TATAR RRD N SUNSETSUNSET LNLN Cro O R Y P H ON GS T N A I I I O R V CreekCreek SP D G Cross County Greenway 0.8 S 275 G A R H W R H WAYNE RD A YS L R L C T 41 579 C CROOKED LN DairyDairy A O A A Cypress Point Park 1.0 N N L N KeystoneKeystone C P O D E D N LAK R FarmFarm C H D H T r Davis Island Park 0.5 U r O O R U Lake U S D SSUNCOAS 568 D A A Bo N G y S Desotto Park 0.3 co W Keystone T K u P N R I m D L E D BrookerBrooker CreekCreek t Rd 589 l RS EN R V d E VVanan DDykeyke RdRd a GRE DeadDead E Shell Point Road 1.2 Y I NNewew TampaTampa R ConeCone RanchRanch VVanan DDykeyke RRdd AV L LIVINGSTON -

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing January - June 2017 6800 North Dale Mabry Highway, Suite 158 Tampa, FL 33614 PH (813) 515-2340 FAX (813) 435-2299 www.elchc.org The Early Learning Coalition of Hillsborough County (ELCHC) is a 501(c)(3), not for profit organization working to advance the access, affordability and quality of early childhood care and education programs in Hillsborough County. Through our Quality Counts for Kids Quality Improvement Program (QCFK) and a host of other resources and supports, we help child care centers and family child care homes to improve their program quality so that all children have quality early learning experiences. Contents How to Use this Quality Listing 4 What is Quality & Why Does it Matter? 5 Programs with Star Rating and/or Gold Seal Accreditation 6 Child Care Centers 7 Family Child Care Homes 19 Programs with a Class One Violation 24 Child Care Centers 25 Family Child Care Homes 26 Resources 28 Special Note/Disclaimer: The information provided in this booklet is gathered from public sources and databases as a courtesy. The information is considered accurate at the time of publication. Due to potential changes in provider/program status during the time period between when this information is gathered, printed and distributed, we encourage you to verify a provider’s status as part of your quality child care shopping efforts. The ELCHC does not individually endorse or recommend one provider or early childhood program over another whether or not they are listed within. January - June 2017 | 3 How to Use this Quality Listing Choosing child care is an important decision that requires last 12 months between November 1, 2015 to October 31, 2016. -

Fpid No. 258337-2 Downtown Tampa Interchange

DETAIL A MATCHLINE A DRAFT Grant Park SACRED HEART ACADEMY James Street James Street These maps are provided for informational and planning PROPOSED NOISE BARRIER TO BE CONSTRUCTED UNDER purposes only. All information is subject to change and WPI SEGMENT NO.44 3770-1 the user of this information should not rely on the data N 5 AUX Emily Street Emily Street ORANGE GROVE 1 Ybor Heights College Hill-Belmont Heights for any other purposes that may require guarantee of 0 60 300 AUX MIDDLE MAGNET 4 1 BORRELL SCHOOL accuracy, timeliness or completeness of information. Feet N PARK (NEBRASKA AVENUE 0 60 300 PARK) DATE: 2/19/2020 5 AUX Feet X 1 26th Avenue AU 4 ROBLES PARK 1 STAGED IMPLEMENTATION PROPOSED NEW AND PLAY GROUND FOR WPI 431746 NOISE BARRIER -1 INTERSTATE 4 (SELMON CONNECTOR TO EAST OF 50th STREET) T B N T e x Plymouth Street IS t S S e ec g ti m on e n 8 t 3 B Adalee Street Adalee Street 3 e 3 nu e v M A e lbou a Hugh Street k r Hugh Street n TE A s T KING'S KID e S R a E A T r CHRISTIAN ve IN b n PROPOSED NEW u e ACADEMY e NOISE BARRIER N Hillsborough Avenue N Highland Pines Hillsborough Avenue Floribraska Avenue INTERSTATE Floribraska Avenue 1 e 3 nu 3 e e v 21st Avenue e t A nu 1 t nu e ll INTERSTATE St. Clair Street ee e v r e ee t v r A h t S A c e S l l C it C h t a Robles Street r M CC t no i 50 e n FRANKLIN MIDDLE e m e 52nd nu MAGNET SCHOOL e C nu 20th Avenue e S Jackson Heights e v N v A N SALESIAN YOUTH CENTER A BO o YS & GIRLS CLUB l 41 rr a OF TAMPA BAY r e t f n a e li a C T 18th Avenue Florence N e Bryant Avenue nu e North Ybor Villa / D.W.W ATER CAREER CENTER v EXISTING NOISE V.M. -

Transforming Tampa's Tomorrow

TRANSFORMING TAMPA’S TOMORROW Blueprint for Tampa’s Future Recommended Operating and Capital Budget Part 2 Fiscal Year 2020 October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020 Recommended Operating and Capital Budget TRANSFORMING TAMPA’S TOMORROW Blueprint for Tampa’s Future Fiscal Year 2020 October 1, 2019 through September 30, 2020 Jane Castor, Mayor Sonya C. Little, Chief Financial Officer Michael D. Perry, Budget Officer ii Table of Contents Part 2 - FY2020 Recommended Operating and Capital Budget FY2020 – FY2024 Capital Improvement Overview . 1 FY2020–FY2024 Capital Improvement Overview . 2 Council District 4 Map . 14 Council District 5 Map . 17 Council District 6 Map . 20 Council District 7 Map . 23 Capital Improvement Program Summaries . 25 Capital Improvement Projects Funded Projects Summary . 26 Capital Improvement Projects Funding Source Summary . 31 Community Investment Tax FY2020-FY2024 . 32 Operational Impacts of Capital Improvement Projects . 33 Capital Improvements Section (CIS) Schedule . 38 Capital Project Detail . 47 Convention Center . 47 Facility Management . 49 Fire Rescue . 70 Golf Courses . 74 Non-Departmental . 78 Parking . 81 Parks and Recreation . 95 Solid Waste . 122 Technology & Innovation . 132 Tampa Police Department . 138 Transportation . 140 Stormwater . 216 Wastewater . 280 Water . 354 Debt . 409 Overview . 410 Summary of City-issued Debt . 410 Primary Types of Debt . 410 Bond Covenants . 411 Continuing Disclosure . 411 Total Principal Debt Composition of City Issued Debt . 412 Principal Outstanding Debt (Governmental & Enterprise) . 413 Rating Agency Analysis . 414 Principal Debt Composition . 416 Governmental Bonds . 416 Governmental Loans . 418 Enterprise Bonds . 419 Enterprise State Revolving Loans . 420 FY2020 Debt Service Schedule . 421 Governmental Debt Service . 421 Enterprise Debt Service . 422 Index . -

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing January - June 2017

Hillsborough Quality Child Care Program Listing January - June 2017 Jan 2017 QualityBooklet .indd 1 12/13/16 4:47 PM 6800 North Dale Mabry Highway, Suite 158 Tampa, FL 33614 PH (813) 515-2340 FAX (813) 435-2299 www.elchc.org The Early Learning Coalition of Hillsborough County (ELCHC) is a 501(c)(3), not for profit organization working to advance the access, affordability and quality of early childhood care and education programs in Hillsborough County. Through our Quality Counts for Kids Quality Improvement Program (QCFK) and a host of other resources and supports, we help child care centers and family child care homes to improve their program quality so that all children have quality early learning experiences. Jan 2017 QualityBooklet .indd 2 12/13/16 4:47 PM Contents How to Use this Quality Listing 4 What is Quality & Why Does it Matter? 5 Programs with Star Rating and/or Gold Seal Accreditation 6 Child Care Centers 7 Family Child Care Homes 19 Programs with a Class One Violation 24 Child Care Centers 25 Family Child Care Homes 26 Resources 28 Special Note/Disclaimer: The information provided in this booklet is gathered from public sources and databases as a courtesy. The information is considered accurate at the time of publication. Due to potential changes in provider/program status during the time period between when this information is gathered, printed and distributed, we encourage you to verify a provider’s status as part of your quality child care shopping efforts. The ELCHC does not individually endorse or recommend one provider or early childhood program over another whether or not they are listed within. -

Models Leaded for Charity Event Governor Visits Local Businesses Deaths 01 Siblings Ruled Accidental Changes in WIC' Program

Celebrating 65 Years In The Tampa Bay Area ' · .'j~-- . /_t • . :.:; • • I II I - . SEE STORY ON PAGE 2 CITY HOSTS EEO TRAINING SEMINAR The City of Tampa's Division of Community Affairs and the U. S. Equal Opportunity Commission hosted an Equal Opportunity Training Seminar last week at Ragan Park Auditorium. Several topics were covered with presentations from Attorney James W. Jones, Manuel Zurita, Field Director, EEO Commission, Tampa; Atty. Yvette D. Daniels and Atty. Roderick 0. Ford. Atty. Ford, center, is shown with City of Tampa employees: Kenneth Perry, Community Affairs Manager; Jesus Loquias, Maritza Betancourt, Ross Silvers, Joann Blount, Margarita Gonzalez, Edna Cade, Deborah Jones, Cherlylene Beall, Rebecca Cortes and Viola Luke. (Photography by BRUNSON) Models leaded Deaths 01 Siblings For Charity Event Ruled Accidental SEE PAGE 3 · - SEE PAGE 16 Governor Visits Changes In WIC' Local Businesses Program Planned SEE PAGE 2 . SEE PAGE 6 ~r------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ~ Features N N ct UJ School Bookkeeper al Business Owner Gets Surprise ~ UJ ..... a. Visit From Governor Sued Over Missing UJ (j) ~ Funds Arrested c (j) Earlier this month, the UJ ::> Tampa Police Department ..... arrested a ss-year-old woman and charged her with grand theft and official mis conduct by falsifying records. She is also a defendant in a civil lawsuit in connection with the case. According to Hillsborough County Jail Records, Ms. Dianne Parker was taken Barber Marven Lindo had into custody on September the opportunity to serve 3rd and charged. She was DIANNE PARKER Governor Charlie Crist !'eleased after posting bond Former Bookkeeper at some authentic Jamaican Erwin Technical Center food during his visit. -

The Tampa Center City Plan Connecting Our Neighborhoods and Our River for Our Future

The Tampa Center City Plan Connecting Our Neighborhoods and Our River for Our Future The Tampa Center City Plan Connecting Our Neighborhoods and Our River for Our Future NOvembeR 2012 Prepared for: City of Tampa IMAGE PLACEHOLDER Prepared by: AECOM 150 North Orange Avenue Orlando, Florida 32801 407 843 6552 AECOM Project No. : 60250712 AECOM Contact : [email protected] In Collaboration With: Parsons Brinckerhoff The Leytham Group ChappellRoberts Blackmon Roberts Group MindMixer Crossroads Engineering Fowler White Boggs PA Stephanie Ferrell FAIA Architect Martin Stone Consulting, LLC © AeCOm Technical Services 2012 This document has been prepared by AeCOm on behalf of the City of Tampa, Florida. This project was made possible through a Sustainable Communities Challenge Grant provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Participation List City Team Workshop Participants bob buckhorn - Mayor Chris Ahern Duncan broyd David Crawley bruce earhart bob mcDonaugh - Economic Development Administrator Art Akins Rod brylawski Nelson Crawley Shannon edge Thomas Snelling - Planning & Development Director Catherine Coyle - Planning Manager Adjoa Akofio-Swah bob buckhorn Darryl Creighton Diane egner Randy Goers - Project Manager beth Alden Arnold buckley Jim Crews Chris elmore J.J. Alexander benjamin buckley Laura Crews michael english Consultant Team Albert Alfonso michelle buckley Daryl Croi maggie enncking Robert Allen Davis burdick Andrea Cullen James evans AECOM ChappellRoberts Joseph Alvarez Andy bushnell Wence Cunnigham -

The Tampa Heights Greenprinting Initiative: an Attempt at Community Building

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 11-19-2004 The aT mpa Heights Greenprinting Initiative: An Attempt at Community Building through Park Revitalization Maya Marie Harper University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation Harper, Maya Marie, "The aT mpa Heights Greenprinting Initiative: An Attempt at Community Building through Park Revitalization" (2004). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/1069 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Tampa Heights Greenprinting Initiative: An Attempt at Community Building through Park Revitalization by Maya Marie Harper A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Susan Greenbaum, Ph.D. Trevor Purcell, Ph.D. Cheryl Rodriguez, Ph.D. Date of Approval: November 19, 2004 Keywords: gentrification, parks, communities, social capital, neighborhoods © Copyright 2004, Maya Marie Harper Table of Contents List of Tables iii List of Figures iv Abstract v Chapter One: Introduction 1 Setting 7 Residents’ Impressions of Tampa -

ANNUAL MANAGEMENT REPORT Board of Commissioners

204.1.19 to 3.31.2020 ANNUAL MANAGEMENT REPORT Board of Commissioners James A. Cloar Bemetra Salter Liggins Billi Johnson-Griffin Chair Vice Chair Resident Commissioner Ben Dachepalli Lorena Hardwick Parker A. Homans Commissioner Commissioner Commissioner OUR GOALS 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 1 Expand Affordable Housing Opportunities by 1,000 units 30% 2 Expand the Economic Stability of the Agency 35% 3 Preserve and Enhance Existing Portfolio 59% Increase Utilization of Bord Members 44% 4 to Achieve Strategic Initiatives Promote and Intensify Self-Sufficiency and Economic 5 51% Opportunities with a Greater Array of Measurable Outcomes 24% 6 Improve Community Relations and Public Awareness Invest in THA Workforce to Ensure Agency is Able to Recruit, 41 % 7 Develop and Retain Qualified Staff at All Levels 8 Deploy Technology to Improve Operational Efficiency 62% and Quality of Service 31% 9 Expand Youth Enrichment Programs Authority-Wide 10 Strengthen Quality of Life Programs to Our Seniors 40% 11 Improve Preparedness forThreats 40% 12 Promote a Culture of Excellence and Innovation 23% 13 Promote Energy Saving and Sustainability 46% Overall Average 41% 0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100% A Word from the President agency name recognition and subsequent From time to time, I mull over different appointment of these staff members to thoughts regarding my message and decided community Boards and Councils: thereby to address matters that sometimes we as these opportunities provide a seat at the President/CEO’s overlook, such as: table when important decisions are made CREATING A STRONG that affect the agency, as a whole. Currently, ORGANIZATIONAL the executive staff of the Housing Authority CULTURE of the City of Tampa is represented with their An organization’s culture consists of the participation in the following community Jerome D.