Signpost Issue No. 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 1 File

•i CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME OF THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND GIVEN IN 1 83 1 BY HENRY WILLIAMS SAGE Cornell University Library Z1023 .C89 Of the decorative illustration of books 3 1924 029 555 426 olin Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029555426 THE EX-LIBRIS SERIES. Edited by Gleeson White. THE DECORATIVE ILLUSTRATION OF BOOKS. BY WALTER CRANE. *ancf& SOJfS THE DECORATIVE OFILLUSTRATION OF BOOKS OLD AND NEW BY WALTER CRANE ^ LONDON: GEORGE BELL AND SONS YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN, W.C. NEW YORK: 66 FIFTH AVENUE MDCCCXCVI 5 PRINTED AT THE CHISWICK PRESS BY CHARLES WHITTINGHAM & CO. TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON, E.C. PREFACE. HIS book had its origin in the course of three (Cantor) Lectures given before the Society of Arts in 1889; they have been amplified and added to, and further chapters have been written, treating of the very active period in printing and decorative book- illustration we have seen since that time, as well as some remarks and suggestions touching the general principles and conditions governing the design of book pages and ornaments. It is not nearly so complete or comprehensive as I could have wished, but there are natural limits to the bulk of a volume in the " Ex-Libris" series, and it has been only possible to carry on such a work in the intervals snatched from the absorbing work of designing. -

The Gothic Revival Character of Ecclesiastical Stained Glass in Britain

Folia Historiae Artium Seria Nowa, t. 17: 2019 / PL ISSN 0071-6723 MARTIN CRAMPIN University of Wales THE GOTHIC REVIVAL CHARACTER OF ECCLESIASTICAL STAINED GLASS IN BRITAIN At the outset of the nineteenth century, commissions for (1637), which has caused some confusion over the subject new pictorial windows for cathedrals, churches and sec- of the window [Fig. 1].3 ular settings in Britain were few and were usually char- The scene at Shrewsbury is painted on rectangular acterised by the practice of painting on glass in enamels. sheets of glass, although the large window is arched and Skilful use of the technique made it possible to achieve an its framework is subdivided into lancets. The shape of the effect that was similar to oil painting, and had dispensed window demonstrates the influence of the Gothic Revival with the need for leading coloured glass together in the for the design of the new Church of St Alkmund, which medieval manner. In the eighteenth century, exponents was a Georgian building of 1793–1795 built to replace the of the technique included William Price, William Peckitt, medieval church that had been pulled down. The Gothic Thomas Jervais and Francis Eginton, and although the ex- Revival was well underway in Britain by the second half quisite painterly qualities of the best of their windows are of the eighteenth century, particularly among aristocratic sometimes exceptional, their reputation was tarnished for patrons who built and re-fashioned their country homes many years following the rejection of the style in Britain with Gothic features, complete with furniture and stained during the mid-nineteenth century.1 glass inspired by the Middle Ages. -

English Catholic Heraldry Since Toleration, 1778–2010

THE COAT OF ARMS The journal of the Heraldry Society Fourth Series Volume I 2018 Number 235 in the original series started in 1952 Founding Editor † John P.B.Brooke-Little, C.V.O, M.A., F.H.S. Honorary Editor Dr Paul A Fox, M.A., F.S.A, F.H.S., F.R.C.P., A.I.H. Reviews Editor Tom O’Donnell, M.A., M.PHIL. Editorial Panel Dr Adrian Ailes, M.A., D.PHIL., F.S.A., F.H.S., A.I.H. Dr Jackson W Armstrong, B.A., M.PHIL., PH.D. Steven Ashley, F.S.A, a.i.h. Dr Claire Boudreau, PH.D., F.R.H.S.C., A.I.H., Chief Herald of Canada Prof D’Arcy J.D.Boulton, M.A., PH.D., D.PHIL., F.S.A., A.I.H. Dr Clive.E.A.Cheesman, M.A., PH.D., F.S.A., Richmond Herald Steen Clemmensen A.I.H. M. Peter D.O’Donoghue, M.A., F.S.A., York Herald Dr Andrew Gray, PH.D., F.H.S. Jun-Prof Dr Torsten Hiltmann, PH.D., a.i.h Prof Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard, PH.D., F.R.Hist.S., A.I.H. Elizabeth Roads, L.V.O., F.S.A., F.H.S., A.I.H, Snawdoun Herald Advertising Manager John J. Tunesi of Liongam, M.Sc., FSA Scot., Hon.F.H.S., Q.G. Guidance for authors will be found online at www.theheraldrysociety.com ENGLISH CATHOLIC HERALDRY SINCE TOLERATION, 1778–2010 J. A. HILTON, PH.D., F.R.Hist.S. -

Gloucester Cathedral Faith, Art and Architecture: 1000 Years

GLOUCESTER CATHEDRAL FAITH, ART AND ARCHITECTURE: 1000 YEARS SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING SUPPLIED BY THE AUTHORS CHAPTER 1 ABBOT SERLO AND THE NORMAN ABBEY Fernie, E. The Architecture of Norman England (Oxford University Press, 2000). Fryer, A., ‘The Gloucestershire Fonts’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 31 (1908), pp 277-9. Available online at http://www2.glos.ac.uk/bgas/tbgas/v031/bg031277.pdf Hare, M., ‘The two Anglo-Saxon minsters of Gloucester’. Deerhurst lecture 1992 (Deerhurst, 1993). Hare, M., ‘The Chronicle of Gregory of Caerwent: a preliminary account, Glevensis 27 (1993), pp. 42-4. Hare, M., ‘Kings Crowns and Festivals: the Origins of Gloucester as a Royal Ceremonial Centre’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 115 (1997), pp. 41-78. Hare, M., ‘Gloucester Abbey, the First Crusade and Robert Curthose’, Friends of Gloucester Cathedral Annual Report 66 (2002), pp. 13-17. Heighway, C., ‘Gloucester Cathedral and Precinct: an archaeological assessment’. Third edition, produced for incorporation in the Gloucester Cathedral Conservation Plan (2003). Available online at http://www.bgas.org.uk/gcar/index.php Heighway, C. M., ‘Reading the stones: archaeological recording at Gloucester Cathedral’, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 126 (2008), pp. 11-30. McAleer, J.P., The Romanesque Church Façade in Britain (New York and London: Garland, 1984). Morris R. K., ‘Ballflower work in Gloucester and its vicinity’, Medieval Art and Architecture at Gloucester and Tewkesbury. British Archaeological Association Conference Transactions for the year 1981 (1985), pp. 99-115. Thompson, K., ‘Robert, duke of Normandy (b. in or after 1050, d. -

Arts & Crafts Stained Glass

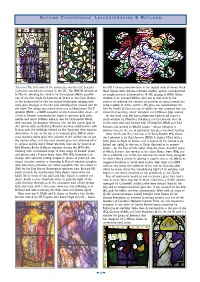

Event Review: Summer lecture Friday 19 June : ‘Exploring Arts & Crafts Stained Glass: a 40-year adventure in light and colour – an illustrated lecture’ by Peter Cormack he lecture was an introduction to some of the main themes Tof the speaker’s newly-published book, Arts & Crafts Stained Glass (Yale University Press for the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art). He began by saying that his discovery of this rich field of research had begun when he was a student at Cambridge in the 1970s, and had developed particularly during his thirty years working as a curator at the William Morris Gallery in London. He paid tribute to the work of other scholars in the field, especially Martin Harrison’s V ictorian Stained Glass , Birkin Haward’s two books on 19th-century glass in Norfolk and Suffolk and Nicola Gordon Bowe’s studies of Irish stained glass. He also emphasized the critical importance of ‘field-work’ – actually going to the places where windows are located to see them in their architectural context. He felt that the internet, with its wealth of images, could sometimes deter people from studying stained glass properly. This was why the BSMGP’s conferences, with their focussed study-visits to churches and other sites, were such a valuable exercise. He then took us through the main narrative of his book, beginning with the pioneers who, from the late 1870s onwards, had championed stained glass as a modern and expressive art form, instead of the formulaic and imitative productions of firms like C. E. Kempe. Henry Holiday was one of the most effective campaigners against commercialism and historicism: his windows Christopher Whall: detail of window in Gloucester Cathedral Lady Chapel, 1901 feature superb figure-drawing combined with a real knowledge of his craft. -

19Th Century English Literature, Presentation Copies, Private Press, Artists' Books, Original Art, Letters, Children's Book

LONDON BOOK FAIR 2016 19th Century English Literature, Presentation Copies, Private Press, Artists’ Books, Original Art, Letters, Children’s Books, African History, Travel, & More Pictured Above: Original Drawings by Max Beerbohm, Items 8* & 9* CURRENCY CONVERSION: $1 = £0.7 * Due to unexpected importation restrictions and fees, several items on this list are not at the fair 1. [Anvil Press] Racine, Jean; John Crowne (translator); Desmond Flower (foreword); Fritz Kredel (illustrator). Andromache: A Tragedy. Freely Translated into English in 1674 from Jean Racine's "Andromaque" Lexington KY: Anvil Press, 1986. Number 11 of 100 copies. According to an article by Burton Milward, the Anvil Press was part of the resurgence of fine press printing in Lexington, led by Joseph Graves, who was influenced and taught by Victor Hammer. The Anvil Press was unusual in that it was an association comprised of ten members, inspired and guided by Hammer and his wife, Carolyn. Their books were printed on any one of the several presses owned by members of the group, and were sold at cost. Bound with black cloth spine and red paper covered boards with red paper title label to spine. Pristine with numerous illustrations by Fritz Kredel. In matching red paper dust jacket with black title to spine and front panels. Creasing to jacket and minor wear to edges. Printed in red and black inks at the Windell Press in Victor Hammer's American & Andromaque uncial types. 51 pages. (#27468) $825 £577 1 2. [Barbarian Press] Barham, Richard; Crispin Elsted, editor and notes; Illustrated by John Lewis Roget and Engraved by the Brothers Dalziel. -

St Etheldreda's, Old Hatfield

ST ETHELDREDA’S, OLD HATFIELD THE TRANSFORMATION OF THE WEST END 01 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Introduction 5 History & Heritage 7 The Proposals 17 The Need 23 An Opportunity 26 The production of this document has been kindly sponsored by Turnberry. 1 FOREWORD St. Etheldreda’s has been the parish church of Bishop’s Hatfield Our predecessors have altered the building over succeeding centuries for many centuries. Named after the patron saint of Ely Cathedral, and now the parish needs to adapt the building to meet the needs of the a monastic foundation to which it was intimately linked until the present congregation. I hope you will agree with me that what the Rector Reformation, it has served our parish faithfully and well from the and his advisers propose is not only practical, but will enhance the beauty eminence which dominates the old town of Hatfield. of the building. Very sensibly they have not only proposed a scheme for the rear of the church, but also a comprehensive plan of restoration. Like many such buildings, it has been added to and adapted to meet the changing demands of liturgy, convenience and prevailing theological There is a great spirit of optimism and community within the parish and fashion. It has acquired over the centuries a handsome square tower, if any group can raise the money to pay for what is proposed, we can. but has lost the distinctive Hertfordshire ‘spike’ that originally topped it. The success of the plans will not only be an outward and visible sign of The Salisbury Chapel, with its remarkable tomb of Robert Cecil, builder that spirit, but a means of bringing the plans for our future to fruition. -

Exhibitions & Art Fairs Exhibiting

Alan J. Poole (Dan Klein Associates) Promoting British & Irish Contemporary Glass. 43 Hugh Street, London SW1V 1QJ. ENGLAND. Tel: (00 44) Ø20 7821 6040. Email: [email protected] Website: www.dankleinglass.com Alan J. Poole’s Contemporary Glass News Letter. A monthly newsletter listing information relating to British & Irish Contemporary Glass events and activities, within the UK, Ireland and internationally. Covering both British and Irish based Artists, those living elsewhere and, any foreign nationals that have ever resided or studied for any period of time in the UK or Ireland. JUNE EDITION 2015. * - indicates new or amended entries since the last edition. 2014. EXHIBITIONS, FAIRS, MARKETS & OPEN STUDIO EVENTS. 08/11/1431/08/15. “Now & Then”. inc: Guan Dong Hai, Yi Peng, Ayako Tani, Wendi Xie & Lu ‘Shelly’ Xue. The Shanghai Museum Of Glass. Shanghai. PRC. Tel: 00 86 21 6618 1970. Email: [email protected] Website: http://en.shmog.org/cp/html/?118.html 15/09/1430/08/15. “North Lands Creative Glass: A Selection Of Works From The North Lands Collection”. inc: Karen Akester, Peter Aldridge, Fabrizia Bazzo, Jane Bruce, Marianne Buus, Tessa Clegg, Katharine Coleman M.B.E., Keith Cummings, Philip Eglin, Carrie Fertig, Catherine Forsyth, Carole Frève, Catherine Forsyth, ‘Gillies · Jones’ (Stephen Gillies & Kate Jones), Mieke Groot, Diana Hobson, Angela Jarman, Alison Kinnaird M.B.E., Richard Meitner, Tobias Møhl, Patricia Niemann, Magdalene Odundo, Zora Palová, Anne Petters, Janusz Pozniak, David Reekie, Bruno Romanelli, Elizabeth Swinburne, Richard Whiteley & Gareth Williams. National Glass Centre. University Of Sunderland. Sunderland. GB. Tel: 0191 515 5555. Email: [email protected] Website: www.nationalglasscentre.com/about/whatson/details/?id=410&to=2014-10- 19%2017:00:00&from=2014-10-19%2000:00:00 2015. -

Churches in West Kent with Fine Stained Glass

CHURCHES IN WEST KENT WITH FINE STAINED GLASS Chiddingstone Causeway, St Luke Chancel windows by WG von Glehn in German expressionist style, 1906. Higham, St Mary (old church) Outstanding chancel windows by Robert Bayne of Heaton, Butler and Bayne influenced by the Pre-Raphaelites, 1863-4. Kemsing, St Mary Nave S window: roundel of Virgin & child, early 14thC. Chancel SE: figure of St Anne, 15thC. Chancel SW by Dixon & Vesey, 1880. Otherwise a good collection of 20thC glass. E & W windows plus N aisle windows by Ninian Comper, 1901-10; nave S by Henry Wilson & Christopher Whall, 1905; N aisle W by Douglas Strachan, 1935. Langton Green, All Saints Important collection of early Pre-Raphaelite glass. Vestry E window by William Morris, c1862. Chancel side windows by Edward Burne-Jones, 1865. Nave W by Burne-Jones, 1865. S aisle W by Morris, Burne-Jones & Ford Madox Brown, 1865. All eclipsed visually by CE Kempe's E window of 1904. Lullingstone, St Botolph E & nave S windows early 16thC. Nave N, painted glass by William Peckitt of York, 1754. N chapel windows contain 3 early 14thC figures, 3 panels dated 1563 (probably Netherlandish) & some armorial glass of the 17th/18thC. Mereworth, St Lawrence Upper E window filled with armorial glass of 16th-18thC. Nave SW magnificent armorial glass of c1750 by William Price. Otherwise a good collection of 19thC glass. Lower E window by Nathaniel Westlake, 1873; nave SE by John Hardman, c1885; nave S central window by Heaton Butler & Bayne, 1889; nave NE by Powell's, 1913. Nettlestead, St Mary Nave glazed some time between 1425 & 1438. -

2017 Leicestershire and Rutland Conference

A UTUMN C ONFERENCE : L EICESTERSHIRE & R UTLAND THURSDAY The first visit of the conference was the 12C Leicester his 1913 E chancel window here in his typical style of heavy black- Cathedral, extensively restored in the 19C. The 1906 W window of lined figures with delicate-coloured shading against a background St Martin donating his cloak is by Christopher Whall, possibly of simple patterns influenced by 14 –15C glazing. A 1920s flower one of the first made by Lowndes & Drury at the Glass House; window is by Leonard Walker, who was at that time in the in the background he uses his typical tinted-glass glazing, with process of reducing the amount of painting on glass, instead just ruby glass lozenges at the top and, notably, white pressed slab for using leading to define outlines. His glass was mould-blown for the snow. The design was reused from one at Manchester. The E him by Powell & Sons, on top of which ore was scattered but not window (1920) – a WWI memorial to the Leicestershire dead – of mixed in, imparting colour variation and brilliance (top centre). Christ in Heaven surrounded by angels in glorious gold-pink, At the third stop, All Saints, Newtown Linford, we found a purple and much brilliant white is also by Christopher Whall, small window by Theodora Salusbury, a local Leicester Arts & with cartoons by daughter Veronica. On the left stands Joan of Crafts artist who had studied with Christopher Whall and Karl Arc (above left), symbolizing Britain’s wartime collaboration with Parsons, and worked in Whall’s studio – whose influence is France, with the buildings behind on fire depicting their wartime obvious here, in the use of gold-pink slab glass and bold leading. -

Newton Country Day School Chapel

Newton Country Day School Chapel In 1925, the Religious of the Sacred Heart transferred their Boston school for girls to the former Tudor-Revival style estate of Loren D. Towle in Newton, Massachusetts. The Boston architectural firm of Maginnis and Walsh (founded in 1898 as Maginnis, Walsh, and Sullivan) built the chapel and a four-story school wing between 1926 and 1928. The senior partner was Charles D. Maginnis (1867-1955), an immigrant from Londonderry, Ireland by way of Toronto, Canada. Maginnis’ leadership revolutionized the architecture of Roman Catholic institutions in America. In 1909, the firm won the competition to design Boston College and in the 1920s would build the library, chapel, and dining hall for the College of the Holy Cross, Worcester. The firm had then become highly honored; Boston College’s Devlin Hall had received the J. Harleston Parker Gold Medal in 1925 and the Carmelite Convent in Carmel, California (1925) and Trinity College Chapel in Washington, DC (1927) both won the American Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal. Maginnis was an admirer of the American Eclectic movement (1880s-1930s) which made use of a variety of historic expressions. The Newton Country Day School Chapel is English 15th- century Gothic. Its style shows an admirably simple practicality, yet evokes warmth through the use of wood for side paneling and roof. In the center, for the students, the seats face the front and the altar. The outer seating, used by the Religious for community prayer, is set in a choir-stall structure, aligned with the sides of the chapel and equipped with seats that fold up when they are not being used. -

Newsletter 300 AMDG Ma R C H 2 0 1 0

stonyhurst association NEWSLETTER NEWSLETTER 300 AMDG ma R C H 2 0 1 0 1 stonyhurst association FRANCIS XAVIER SCHOLARSHIPS NEWSLETTER The St Francis Xavier Award is a new scholarship being awarded for entry to NEWSLETTER 300 AMDG M A RCH 2010 Stonyhurst. These awards are available at 11+ and 13+ for up to 10 students who, in the opinion of the selection panel, are most likely to benefit from, and contribute to, life as full boarders in a Catholic boarding school. Assessments for the awards comprise written examinations and one or more interviews. CONTENTS IN THIS ISSUE Applicants for the award are expected to be bright pupils who will fully participate in all aspects of boarding school life here at Stonyhurst. St Francis Xavier Award holders will automatically benefit from a fee remission of 20% and Diary of Events 4 thereafter may also apply for a means-tested bursary, worth up to a further 50% From the Chairman 5 off the full boarding fees. Page 13: 2010 marks the 400th anniversary The award is intended to foster the virtues of belief, ambition and hard work Congratulations 6 of the death of the College founder, Robert which Francis Xavier exemplified in pushing out the boundaries of the Christian Parsons SJ, which will be celebrated on faith. We believe that a Stonyhurst education can give young people a chance to Correspondence April 29th (see p. 12). Joe Egerton calls for a reassessment of his life and work. emulate St Francis and become tenacious pioneers for the modern world. & Miscellany 7 If you have a child or know of a child who would be a potential St Francis Xavier candidate in 2011 then please do get in touch with our admissions department on Reunions & Convivia 11 01254 827073/93 or email them at [email protected].