Heidi Niskanen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scientific Journal of Business & Innovation

Volume 1 Issue 1 · January–June 2021 Scientific Journal of Business & Innovation ISSN 2749-6899 iii Table of Contents Editor-in-Chief iv Editorial Prof. Dr. Kyriakos Kouveliotis v Journal Information vi About BSBI Associate Editors 01 Commercial Importanceof a Freshwater Dr. Elham Shirvani Prawn, Macrobrachium Lamarrei: Dr. Maryam Mansuri a Case Study in Its Food Security Aspects 05 Sentiment Analysis of YouTube Video Honorary Senior Advisory Editor Comments Using Big Data: Prof. Dr. Emidia Vagnoni, Helping a Video Go Viral University of Ferrara Italy 09 Embodied Cognition and Subject Roles in the History of Philosophy Editorial Board 13 Relationship Between Investments Prof. Dr. Kyriakos Kouveliotis in Intellectual Capital and Financial Dr. Anastasios Fountis Performance: Evidence from Serbian Hotel Dr. Elham Shirvani Industry 2013–2017 Dr. Maryam Mansuri 21 Direction in Global Market Coping Dr. Anastasia Alevriadou Strategies: Virgin Airlines Case Study Dr. Milos Petkovic 31 A Case Study on Successful Implementation Dr. (MD) Ahmed ElBarawi of Ethics and Responsible Business Dr. Moumita Mukherjee Policies at a Corporate Level Dr. Desislava Valerieva Dimitrova 35 The Status of Sustainable Health Dr. Vivek Arunachalam Governance and Future Role of Eco-Tourism Dr. Christos Lemonakis Model for Eradicating Ex-Ante Child Health Dr. Marios Menexiadis Poverty in Riverine West Bengal, India Dr. Chaditsa Poulatova 43 Will Dexit Follow the Brexit and the Ms. Mina Shokri Consequences of the German Economy Ms. Katherine Boxall and European Union Mr. Anuj Batta 47 PR Watches — Innovative Solution Ms. Zoi Kerou in Alzheimer’s Care Mr. Konstantinos Skamagkas 51 Digital Marketing Campaign for Adidas Ms. Kathrin Bremer to Increase Customer Lifetime Value Ms. -

Brandmanagement Im Sportar- Tikelmarkt

BACHELORARBEIT Alessandro Trageser Brandmanagement im Sportar- tikelmarkt 2017 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Brandmanagement im Sportarti- kelmarkt Autor: Alessandro Trageser Studiengang: Business Management Seminargruppe: BM14wD4-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Eckehard Krah Zweitprüfer: Peter Kaess Einreichung: Frankfurt am Main, 05.06.2017 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS Brandmanagement in the sporting goods market author: Alessandro Trageser course of studies: Business Management seminar group: BM14wD4-B first examiner: Prof. Dr. Eckehard Krah second examiner: Peter Kaess submission: Frankfurt, 05.06.2017 Bibliografische Angaben Nachname, Vorname: Trageser, Alessandro Thema der Bachelorarbeit: Brandmanagement im Sportartikelmarkt Topic of thesis: Brandmanagement in the sporting goods market 64 Seiten, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2017 Abstract Intention der Arbeit ist es, die Erfolgsfaktoren für ein gesundes bzw. erfolgreiches Brandmanagement eines Unternehmens im Sportartikelmarkt herauszuarbeiten. Im Fokus des Forschungsinteresses steht dabei die Frage nach dem langfristigen Aufbau der Marken- und Marketingstrategie wie auch der darauf aufbauenden Kommunikati- onsinstrumente. Anhand der Analyse von theoretischen Strategien im Marketingbe- reich und Konzeptionen der Markenkommunikation macht der Verfasser auf deren Bedeutung im Sportartikelmarkt aufmerksam. Diese werden anhand eines gewählten Praxisbeispiels geprüft. Mit den gewählten Fragestellungen und den zuvor herausge- arbeiteten Daten und Fakten des Unternehmens Adidas, stellt der Verfasser dessen Erfolg und die damit verbundenen, wirkenden Erfolgsfaktoren dar. Die Arbeit zeigt, dass ein Unternehmen auf dem Sportartikelmarkt nur erfolgreich sein kann, wenn die allgemeine Führung der Marke und alle damit verbundenen Marketingmaßnahmen im Sinne der Markenphilosophie abgestimmt sind. Ziel der Unternehmen, unabhängig vom Sportartikelmarkt, ist es dabei einen Mehrwert für die eigenen Anspruchsgruppen zu schaffen, welcher emotional an die Marke bindet. -

Universita' Degli Studi Di Padova

UNIVERSITA’ DEGLI STUDI DI PADOVA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE ECONOMICHE ED AZIENDALI “M.FANNO” CORSO DI LAUREA IN ECONOMIA PROVA FINALE “NON SOLO SCARPE: ADIDAS x PARLEY” RELATORE: CH.MO PROF. ROMANO CAPPELLARI LAUREANDA: SOFIA SACCO STEVANELLA MATRICOLA N. 1113129 ANNO ACCADEMICO 2017 – 2018 1 INDICE INTRODUZIONE .................................................................................................................... 3 1. IL RISPETTO PER L’AMBIENTE ................................................................................... 5 1.1 IL CONSUM-AUTORE/ATTORE .................................................................................. 5 1.2 INDICATORI DI PERFORMANCE DELLA SOSTENIBILITÀ ................................. 10 1.3. ORGANIZZAZIONI E PROGRAMMI VESTONO GREEN ..................................... 13 1.3.1. COPENAGHEN FASHION SUMMIT .................................................................. 14 1.3.2. GREENPEACE – DETOX CATWALK ................................................................ 17 1.3.3. PARLEY FOR THE OCEANS ............................................................................... 19 2. L’IMPATTO AMBIENTALE DELLA FASHION INDUSTRY ................................... 22 2.1. I PRINCIPALI DANNI PRODOTTI DALLA MODA SULL’AMBIENTE ................ 22 2.2 ALCUNE POSSIBILI SOLUZIONI E INNOVAZIONI ............................................... 25 2.3. NEL CALZATURIERO ................................................................................................ 28 3. ADIDAS x PARLEY ......................................................................................................... -

2021 Edition

2021 Edition Lo senti addosso anche quando non giochi. Un kit ti fa sentire parte della squadra. Con un kit non è mai solo una partitella, diventa ufficiale. Un kit rende tutto più vero. © 2020 adidas AG A KIT MAKES IT REAL When you’ve got a kit, it means you belong. You’re part of a community. A family. You’re not just a ringer or a last-minute replacement. You’re a fully fledged member of the club. When you’ve got a kit – it becomes a part of you. It’s your identity. Your armour. It says who you are and what you represent. You wear it, even when you’re not wearing it. In this kit, you’re part of the team. A kit makes it more than a casual kick around. A kit makes it official. A kit makes it real. 4 CICLO DI VITA FINO A FINE FEBBRAIO CONDIVO 21 JERSEYS 2023 CONDIVO 20 2022 CAMPEON 21 2023 STRIPED 21 2024 REGISTA 20 2022 TABELA 18 2022 SQUADRA 21 2024 ENTRADA 18 2023 ESTRO 19 2024 CONDIVO GK 21 2022 SQUADRA 21 GK 2024 REFEREE 2022 CONDIVO 21 SHORTS 2023 CONDIVO 20 2022 TASTIGO 19 2021 / 2023 SQUADRA 21 2024 PARMA 16 2022 TIERRO 2025 CONDIVO 21 TRAINING 2023 CONDIVO 20 2022 TIRO 21 2023 SQUADRA 21 2024 CORE 18 2022 TEAM 19 JUNE 2021 TIRO BAGS & ACCESSORIES HARDWARE / END OF 2022 ACC TIRO BALLS END OF 2022 6 SOMMARI0 CICLO DI VITA 6 TRAININGWEAR TECNOLOGIE 8 CONDIVO 21 78 SOSTENIBILITÀ 10 CONDIVO 20 86 TEAMWEAR LINEUP 2021 12 CONDIVO 18 98 CLUBS AND FEDERATIONS 14 TIRO 21 100 SQUADRA 21 112 CORE 18 122 MATCHWEAR CONDIVO 21 16 CONDIVO 20 20 WOMEN’S CAMPEON 21 26 CONDIVO 20 MATCHWEAR 138 STRIPED 21 30 SQUADRA 21 MATCHWEAR 144 REGISTA 20 34 CONDIVO 20 TRAININGWEAR 150 TABELA 18 38 TIRO 21 TRAININGWEAR 156 SQUADRA 21 42 WOMEN’S BRAS 165 ENTRADA 18 46 ESTRO 19 50 TEAM 19 166 TECHFIT 54 ACCESSORIES 178 BASE TEE 21 56 FOOTBALLS 186 CONDIVO 21 GOALKEEPER 58 SIZE CHART 192 SQUADRA 21 GOALKEEPER 62 REFEREE 64 SHORTS 66 TUTTI I PREZZI INDICATI NEL PRESENTE CATALOGO SONO GLI UNICI PREZZI AL SOCKS 72 DETTAGLIO RACCOMANDATI DA ADIDAS. -

K291 Description.Indd

AGON SportsWorld 1 76th Auction Descriptions AGON SportsWorld 2 76th Auction 76th AGON Sportsmemorabilia Auction 11th March 2020 Contents 11th March 2020 Lots 1 - 1606 Football World Cup 4 German match worn shirts 49 Football in general 70 German Football 76 International Football 87 International match worn shirts 99 Football Autographs 106 Olympics 115 Olympic Autographs 168 Other Sports 184 The essentials in a few words: Bidsheet extra sheet - all prices are estimates - they do not include value-added tax; 7% VAT will be additionally charged with the invoice. - if you cannot attend the public auction, you may send us a written order for your bidding. - in case of written bids the award occurs in an optimal way. For example:estimate price for the lot is 100,- €. You bid 120,- €. a) you are the only bidder. You obtain the lot for 100,-€. b) Someone else bids 100,- €. You obtain the lot for 110,- €. c) Someone else bids 130,- €. You lose. - In special cases and according to an agreement with the auctioneer you may bid by telephone during the auction. (English and French telephone service is availab- le). - The price called out ie. your bid is the award price without fee and VAT. - The auction fee amounts to 16,5%. - The total price is composed as follows: award price + 16,5% fee = subtotal + 7% VAT = total price. - The items can be paid and taken immediately after the auction. Successful orders by phone or letter will be delivered by mail (if no other arrange- ment has been made). In this case post and package is payable by the bidder. -

Impact of Innovation on Consumer's Brand Perception

UNIVERSITY OF LJUBLJANA FACULTY OF ECONOMICS MASTER’S THESIS IMPACT OF INNOVATION ON CONSUMER'S BRAND PERCEPTION Ljubljana, June 2018 ŽIVA BENČINA TEJA BURJA AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT The undersigned Živa Benčina, a student at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Economics, (hereinafter: FELU), the author of this written final work of studies with the title Impact of innovation on consumer’s brand perception, prepared under supervision of Full Professor Vesna Žabkar, PhD, DECLARE 1. this written final work of studies to be based on the results of my own research; 2. the printed form of this written final work of studies to be identical to its electronic form; 3. the text of this written final work of studies to be language-edited and technically in adherence with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works, which means that I cited and/or quoted works and opinions of other authors in this written final work of studies in accordance with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works; 4. to be aware of the fact that plagiarism (in written or graphical form) is a criminal offense and can be prosecuted in accordance with the Criminal Code of the Republic of Slovenia; 5. to be aware of the consequences a proven plagiarism charge based on the this written final work could have for my status at the FELU in accordance with the relevant FELU Rules; 6. to have obtained all the necessary permits to use the data and works of other authors which are (in written or graphical form) referred to in this written final work of studies and to have clearly marked them; 7. -

Ethical Consumer Issue 185, July/August 2020

£4·25 185 July/Aug 2020 www.ethicalconsumer.org Who profits when life goes online? Guides to SHOPPING GUIDES TO shoes & l video conferencing trainers l ethical online retailers CAPITAL AT RISK. INVESTMENTS ARE LONG TERM AND MAY NOT BE READILY REALISABLE. ABUNDANCE IS AUTHORISED AND REGULATED BY THE FINANCIAL CONDUCT AUTHORITY (525432). Making money is great. But only if you’ve got a planet left to spend it on. abundanceinvestment.com Mobilise your money for good Over 200 mens and NEW womens styles! NOW IN KOMODO ECO SNEAKO’S NAVY GREY MINT WHITE Tel: 01273 691913 | [email protected] vegshoes.com ethical consumer 1/2 page ad 0520.indd 1 27/05/2020 13:11 2 Ethical Consumer July/August 2020 ETHICAL CONSUMER Editorial WHO’S WHO rom our lockdown bunkers we and was published in The Observer THIS ISSUE’S EDITOR Josie Wexler bring you the latest issue of Letters section on 24/5/2020. PROOFING Ciara Maginness (Little Blue Pencil) WRITERS/RESEARCHERS Jane Turner, Tim Hunt, Ethical Consumer, which features This letter calls for us to “bake-in” Rob Harrison, Anna Clayton, Josie Wexler, two guides – to video calls and positive changes like the increase Ruth Strange, Mackenzie Denyer, Clare Carlile, Fethical online retailers, which are in video conferencing, reverse the Francesca de la Torre, Alex Crumbie, Tom Bryson, inspired by the last few months’ shift marketisation of the healthcare system Billy Saundry, Jasmine Owens REGULAR CONTRIBUTORS Simon Birch, Colin Birch into the virtual world. which undermined our ability to deal DESIGN Tom Lynton As we discuss in the guides, there with Covid, and for us to deal with future LAYOUT Adele Armistead (Moonloft), Jane Turner are both good and bad sides to this threats, like the ecological crisis. -

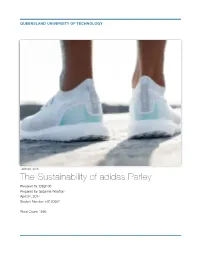

Assignment 2 Final

QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Johnson, 2016 The Sustainability of adidas Parley Prepared for: DEB100 Prepared by: Suzanne Wootton April 24, 2017 Student Number: n9180567 Word Count: 1566 QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Introduction 3 Up-cycle, Down-cycle, Danger-cycle 4 WHAT IS UP-CYCLING, DOWN-CYCLING, AND DANGER-CYCLING? 4 STRENGTHS 4 WEAKNESSES AND THREATS 4 OPPORTUNITIES 5 Nature as culture 6 WHAT IS NATURE AS CULTURE? 6 STRENGTHS 6 WEAKNESSES AND THREATS 6 OPPORTUNITIES 7 Public, Private, Non-Profit 8 WHAT ARE PUBLIC, PRIVATE, AND NON-PROFIT COMPANIES? 8 STRENGTHS 8 WEAKNESSES AND THREATS 8 OPPORTUNITIES 8 Conclusion 9 Bibliography 10 QUEENSLAND UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY INTRODUCTION The Three Stripes are an iconic symbol of Adolf Dassler himself. A symbol of social acceptance to the Superstar clad teenagers, or perhaps a symbol of childhood to the Gazelle aficionados. Above all of these, though, one shoe has triumphed as a symbol of sustainability. Laced through the pages of magazines, the adidas Parley collaboration has been making waves around the world since 2015. adidas, 2015 It was a heart warming moment when adidas announced the birth of a collaboration with Parley, saviours of the sea. adidas, since then, has vowed to continue their ongoing work with Parley, using recycled plastic from Maldivian waters to create up cycled sportswear. In the age of disposable products, plastic can seem inescapable. With some plastic items only having a life span of a few seconds, it is not hard to believe that 8.8 million tonnes of plastic gets dumped into global waters annually (Sifferlin, 2015).