Spacetime Constraints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Swimming in Spacetime: Motion by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape

RESEARCH ARTICLE tation of the two disks can be accomplished without external torques, for example, by fixing Swimming in Spacetime: Motion the distance between the centers by a rigid circu- lar arc and then contracting a tension wire sym- by Cyclic Changes in Body Shape metrically attached to the outer edge of the two caps. Nevertheless, their contributions to the zˆ Jack Wisdom component of the angular momentum are parallel and add to give a nonzero angular momentum. Cyclic changes in the shape of a quasi-rigid body on a curved manifold can lead Other components of the angular momentum are to net translation and/or rotation of the body. The amount of translation zero. The total angular momentum of the system depends on the intrinsic curvature of the manifold. Presuming spacetime is a is zero, so the angular momentum due to twisting curved manifold as portrayed by general relativity, translation in space can be must be balanced by the angular momentum of accomplished simply by cyclic changes in the shape of a body, without any the motion of the system around the sphere. external forces. A net rotation of the system can be ac- complished by taking the internal configura- The motion of a swimmer at low Reynolds of cyclic changes in their shape. Then, presum- tion of the system through a cycle. A cycle number is determined by the geometry of the ing spacetime is a curved manifold as portrayed may be accomplished by increasing by ⌬ sequence of shapes that the swimmer assumes by general relativity, I show that net translations while holding fixed, then increasing by (1). -

Foundations of Newtonian Dynamics: an Axiomatic Approach For

Foundations of Newtonian Dynamics: 1 An Axiomatic Approach for the Thinking Student C. J. Papachristou 2 Department of Physical Sciences, Hellenic Naval Academy, Piraeus 18539, Greece Abstract. Despite its apparent simplicity, Newtonian mechanics contains conceptual subtleties that may cause some confusion to the deep-thinking student. These subtle- ties concern fundamental issues such as, e.g., the number of independent laws needed to formulate the theory, or, the distinction between genuine physical laws and deriva- tive theorems. This article attempts to clarify these issues for the benefit of the stu- dent by revisiting the foundations of Newtonian dynamics and by proposing a rigor- ous axiomatic approach to the subject. This theoretical scheme is built upon two fun- damental postulates, namely, conservation of momentum and superposition property for interactions. Newton’s laws, as well as all familiar theorems of mechanics, are shown to follow from these basic principles. 1. Introduction Teaching introductory mechanics can be a major challenge, especially in a class of students that are not willing to take anything for granted! The problem is that, even some of the most prestigious textbooks on the subject may leave the student with some degree of confusion, which manifests itself in questions like the following: • Is the law of inertia (Newton’s first law) a law of motion (of free bodies) or is it a statement of existence (of inertial reference frames)? • Are the first two of Newton’s laws independent of each other? It appears that -

Phoronomy: Space, Construction, and Mathematizing Motion Marius Stan

To appear in Bennett McNulty (ed.), Kant’s Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science: A Critical Guide. Cambridge University Press. Phoronomy: space, construction, and mathematizing motion Marius Stan With his chapter, Phoronomy, Kant defies even the seasoned interpreter of his philosophy of physics.1 Exegetes have given it little attention, and un- derstandably so: his aims are opaque, his turns in argument little motivated, and his context mysterious, which makes his project there look alienating. I seek to illuminate here some of the darker corners in that chapter. Specifi- cally, I aim to clarify three notions in it: his concepts of velocity, of compo- site motion, and of the construction required to compose motions. I defend three theses about Kant. 1) his choice of velocity concept is ul- timately insufficient. 2) he sided with the rationalist faction in the early- modern debate on directed quantities. 3) it remains an open question if his algebra of motion is a priori, though he believed it was. I begin in § 1 by explaining Kant’s notion of phoronomy and its argu- ment structure in his chapter. In § 2, I present four pictures of velocity cur- rent in Kant’s century, and I assess the one he chose. My § 3 is in three parts: a historical account of why algebra of motion became a topic of early modern debate; a synopsis of the two sides that emerged then; and a brief account of his contribution to the debate. Finally, § 4 assesses how general his account of composite motion is, and if it counts as a priori knowledge. -

Central Limit Theorems for the Brownian Motion on Large Unitary Groups

CENTRAL LIMIT THEOREMS FOR THE BROWNIAN MOTION ON LARGE UNITARY GROUPS FLORENT BENAYCH-GEORGES Abstract. In this paper, we are concerned with the large n limit of the distributions of linear combinations of the entries of a Brownian motion on the group of n × n unitary matrices. We prove that the process of such a linear combination converges to a Gaussian one. Various scales of time and various initial distributions are considered, giving rise to various limit processes, related to the geometric construction of the unitary Brownian motion. As an application, we propose a very short proof of the asymptotic Gaussian feature of the entries of Haar distributed random unitary matrices, a result already proved by Diaconis et al. Abstract. Dans cet article, on consid`erela loi limite, lorsque n tend vers l’infini, de combinaisons lin´eairesdes coefficients d'un mouvement Brownien sur le groupe des matri- ces unitaires n × n. On prouve que le processus d'une telle combinaison lin´eaireconverge vers un processus gaussien. Diff´erentes ´echelles de temps et diff´erentes lois initiales sont consid´er´ees,donnant lieu `aplusieurs processus limites, li´es`ala construction g´eom´etrique du mouvement Brownien unitaire. En application, on propose une preuve tr`escourte du caract`ereasymptotiquement gaussien des coefficients d'une matrice unitaire distribu´ee selon la mesure de Haar, un r´esultatd´ej`aprouv´epar Diaconis et al. Introduction There is a natural definition of Brownian motion on any compact Lie group, whose distribution is sometimes called the heat kernel measure. Mainly due to its relations with the object from free probability theory called the free unitary Brownian motion and with the two-dimentional Yang-Mills theory, the Brownian motion on large unitary groups has appeared in several papers during the last decade. -

Rigid Motion – a Transformation That Preserves Distance and Angle Measure (The Shapes Are Congruent, Angles Are Congruent)

REVIEW OF TRANSFORMATIONS GEOMETRY Rigid motion – A transformation that preserves distance and angle measure (the shapes are congruent, angles are congruent). Isometry – A transformation that preserves distance (the shapes are congruent). Direct Isometry – A transformation that preserves orientation, the order of the lettering (ABCD) in the figure and the image are the same, either both clockwise or both counterclockwise (the shapes are congruent). Opposite Isometry – A transformation that DOES NOT preserve orientation, the order of the lettering (ABCD) is reversed, either clockwise or counterclockwise becomes clockwise (the shapes are congruent). Composition of transformations – is a combination of 2 or more transformations. In a composition, you perform each transformation on the image of the preceding transformation. Example: rRx axis O,180 , the little circle tells us that this is a composition of transformations, we also execute the transformations from right to left (backwards). If you would like a visual of this information or if you would like to quiz yourself, go to http://www.mathsisfun.com/geometry/transformations.html. Line Reflection Point Reflection Translations (Shift) Rotations (Turn) Glide Reflection Dilations (Multiply) Rigid Motion Rigid Motion Rigid Motion Rigid Motion Rigid Motion Not a rigid motion Opposite isometry Direct isometry Direct isometry Direct isometry Opposite isometry NOT an isometry Reverse orientation Same orientation Same orientation Same orientation Reverse orientation Same orientation Properties preserved: Properties preserved: Properties preserved: Properties preserved: Properties preserved: Properties preserved: 1. Distance 1. Distance 1. Distance 1. Distance 1. Distance 1. Angle measure 2. Angle measure 2. Angle measure 2. Angle measure 2. Angle measure 2. Angle measure 2. -

Physics, Philosophy, and the Foundations of Geometry Michael Friedman

Ditilogos 19 (2002), pp. 121-143. PHYSICS, PHILOSOPHY, AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF GEOMETRY MICHAEL FRIEDMAN Twentieth century philosophy of geometry is a development and continuation, of sorts, of late nineteenth century work on the mathematical foundations of geometry. Reichenbach, Schlick, a nd Carnap appealed to the earlier work of Riemann, Helmholtz, Poincare, and Hilbert, in particular, in articulating their new view of the nature and character of geometrical knowledge. This view took its starting point from a rejection of Kant's conception of the synthetic a priori status of specifically Euclidean geometry-and, indeed, from a rejection of any role at all for spatial intuition within pure mathematics. We must sharply distinguish, accordingly, between pure or mathematical geometry, which is an essentially uninterpreted axiomatic system making no reference whatsoever to spatial intuition or any other kind of extra axiomatic or extra-formal content, and applied or physical geometry, which then attempts to coordinate such an uninterpreted formal sys tern with some domain of physical facts given by experience. Since, however, there is always an optional element of decision in setting up such a coordination in the first place (we may coordinate the uninterpreted terms of purely formal geometry with light rays, stretched strings, rigid bodies, or whatever), the question of the geometry of physical space is not a purely empirical one but rather essentially involves an irreducibly conventional and in some sense arbitrary choice. In the end, there is therefore no fact of the matter whether physical space is E uclidean or non-Euclidean, except relative to one or another essentially arbitrary stipulation coordinating the uninterpreted terms of pure mathematical geometry with some or another empirical physical phenomenon. -

![Arxiv:1704.03334V1 [Physics.Gen-Ph] 8 Apr 2017 Oin Ffltsaeadtime](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3310/arxiv-1704-03334v1-physics-gen-ph-8-apr-2017-oin-f-tsaeadtime-1063310.webp)

Arxiv:1704.03334V1 [Physics.Gen-Ph] 8 Apr 2017 Oin Ffltsaeadtime

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT THE GEOMETRY OF SPACE? B. E. EICHINGER Department of Chemistry, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195-1700 Abstract. The belief that three dimensional space is infinite and flat in the absence of matter is a canon of physics that has been in place since the time of Newton. The assumption that space is flat at infinity has guided several modern physical theories. But what do we actually know to support this belief? A simple argument, called the ”Telescope Principle”, asserts that all that we can know about space is bounded by observations. Physical theories are best when they can be verified by observations, and that should also apply to the geometry of space. The Telescope Principle is simple to state, but it leads to very interesting insights into relativity and Yang-Mills theory via projective equivalences of their respective spaces. 1. Newton and the Euclidean Background Newton asserted the existence of an Absolute Space which is infinite, three dimensional, and Euclidean.[1] This is a remarkable statement. How could Newton know anything about the nature of space at infinity? Obviously, he could not know what space is like at infinity, so what motivated this assertion (apart from Newton’s desire to make space the sensorium of an infinite God)? Perhaps it was that the geometric tools available to him at the time were restricted to the principles of Euclidean plane geometry and its extension to three dimensions, in which infinite space is inferred from the parallel postulate. Given these limited mathematical resources, there was really no other choice than Euclid for a description of the geometry of space within which to formulate a theory of motion of material bodies. -

Using Particles to Sample and Control Implicit Surfaces

Using Particles to Sample and Control Implicit Surfaces Andrew P. Witkin Paul S. Heckbert Department of Computer Science Carnegie Mellon University Abstract In this paper, we present a new particle-based approach to sam- We present a new particle-based approach to sampling and con- pling and shape control of implicit surfaces that addresses these trolling implicit surfaces. A simple constraint locks a set of particles problems. At the heart of our approach is a simple constraint that onto a surface while the particles and the surface move. We use the locks a collection of particles onto an implicit surface while both constraint to make surfaces follow particles, and to make particles the particles and the surface move. We can use the constraint to follow surfaces. We implement control points for direct manipula- make the surface follow the particles, or to make the particles follow tion by specifying particle motions, then solving for surface motion the surface. Our formulation is differential: we specify and solve that maintains the constraint. For sampling and rendering, we run the for velocities rather than positions, and the behavior of the system constraint in the other direction, creating floater particles that roam is governed by differential equations that integrate these velocities freely over the surface. Local repulsion is used to make floaters over time. spread evenly across the surface. By varying the radius of repulsion We control surface shape by moving particles interactively, solv- adaptively, and fissioning or killing particles based on the local den- ing for surface motion that keeps the particles on the surface. -

Chapter 1 Rigid Body Kinematics

Chapter 1 Rigid Body Kinematics 1.1 Introduction This chapter builds up the basic language and tools to describe the motion of a rigid body – this is called rigid body kinematics. This material will be the foundation for describing general mech- anisms consisting of interconnected rigid bodies in various topologies that are the focus of this book. Only the geometric property of the body and its evolution in time will be studied; the re- sponse of the body to externally applied forces is covered in Chapter ?? under the topic of rigid body dynamics. Rigid body kinematics is not only useful in the analysis of robotic mechanisms, but also has many other applications, such as in the analysis of planetary motion, ground, air, and water vehicles, limbs and bodies of humans and animals, and computer graphics and virtual reality. Indeed, in 1765, motivated by the precession of the equinoxes, Leonhard Euler decomposed a rigid body motion to a translation and rotation, parameterized rotation by three principal-axis rotation (Euler angles), and proved the famous Euler’s rotation theorem [?]. A body is rigid if the distance between any two points fixed with respect to the body remains constant. If the body is free to move and rotate in space, it has 6 degree-of-freedom (DOF), 3 trans- lational and 3 rotational, if we consider both translation and rotation. If the body is constrained in a plane, then it is 3-DOF, 2 translational and 1 rotational. We will adopt a coordinate-free ap- proach as in [?, ?] and use geometric, rather than purely algebraic, arguments as much as possible. -

Real-Time Object Motion and 3D Localization from Geometry

Real-Time Object Motion and 3D Localization from Geometry DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Young Jin Lee Graduate Program in Geodetic Science and Surveying The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Alper Yilmaz, Advisor Alan Saalfeld Ralph R. B. von Frese Copyright by Young Jin Lee 2014 Abstract Knowing the position of an object in real-time has tremendous meaning. The most widely used and well-known positioning system is GPS (Global Positioning System), which is now used widely as invisible infrastructure. However, GPS is only available for outdoor uses. GPS signals are not available for most indoor scenarios. Although much research has focused on vision-based indoor positioning, it is still a challenging problem because of limitations in both the vision sensor itself and processing power. This dissertation focuses on real-time 3D positioning of a moving object using multiple static cameras. A real-time, multiple static camera system for object detection, tracking, and 3D positioning that is run on a single laptop computer was designed and implemented. The system successfully shows less than ±5 mm in real-time 3D positioning accuracy at an update rate of 6 Hz to 10 Hz in a room measuring 8×5×2.5 meters. Implementation and experimental analysis has demonstrated that this system can be used for real-time indoor object positioning. In addition, ‘collinearity condition equations of motion’ were derived that represent the geometric relationship between 2D motions and 3D motion. From these equations, a ‘tracking from geometry’ method was developed that combines these collinearity condition equations of motion with an existing tracking method to simultaneously estimate 3D motion as well as 2D motions directly from the stereo camera system. -

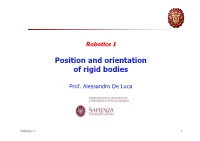

Position and Orientation of Rigid Bodies

Robotics 1 Position and orientation of rigid bodies Prof. Alessandro De Luca Robotics 1 1 Position and orientation right-handed orthogonal RFB rigid body Reference Frames A 3 • position: pAB (vector ! R ), B expressed in RF (use of coordinates I A RFA other than Cartesian is possible, e.g. pAB cylindrical or spherical) • orientation: orthonormal 3x3 matrix T -1 A B A (R = R " RB RA = I), with det = +1 A A A A RB = [ xB yB zB] • xA yA zA (xB yB zB) are unit vectors (with unitary norm) of frame RFA (RFB) A • components in RB are the direction cosines of the axes of RFB with respect to (w.r.t.) RFA Robotics 1 2 Rotation matrix T T T direction cosine of xA xB xA yB xA zB zB w.r.t. xA AR = y T x y T y y T z orthonormal, B A B A B A B T T T with det = +1 zA xB zA yB zA zB algebraic structure chain rule property of a group SO(3) (neutral element = I; k i k inverse element = RT) Ri ! Rj = Rj orientation of RFi orientation of RFj w.r.t. RFk w.r.t. RFk orientation of RFj w.r.t. RFi NOTE: in general, the product of rotation matrices does not commute! Robotics 1 3 Change of coordinates z0 0 px 0P = 0p = 1p 0x + 1p 0y + 1p 0z z1 • P y x 1 y 1 z 1 0p z 1 px y 1 0 0 0 1 = x1 y1 z1 py 1 pz RF1 y0 = 0R 1P RF0 1 x0 0 the rotation matrix R1 (i.e., the orientation of RF1 w.r.t. -

Large Steps in Cloth Simulation David Baraff Andrew Witkin

SIGGRAPH 98, Orlando, July 19±24 COMPUTER GRAPHICS Proceedings, Annual Conference Series, 1998 Large Steps in Cloth Simulation David Baraff Andrew Witkin Robotics Institute Carnegie Mellon University Abstract tion of xÐyields the cloth's internal energy, and F (a function of x and x) describes other forces (air-drag, contact and constraint forces, The bottle-neck in most cloth simulation systems is that time steps internal˙ damping, etc.) acting on the cloth. must be small to avoid numerical instability. This paper describes In this paper, we describe a cloth simulation system that is much a cloth simulation system that can stably take large time steps. The faster than previously reported simulation systems. Our system's simulation system couples a new technique for enforcing constraints faster performance begins with the choice of an implicit numerical on individual cloth particles with an implicit integration method. integration method to solve equation (1). The reader should note The simulator models cloth as a triangular mesh, with internal cloth that the use of implicit integration methods in cloth simulation is far forces derived using a simple continuum formulation that supports from novel: initial work by Terzopoulos et al. [15, 16, 17] applied modeling operations such as local anisotropic stretch or compres- such methods to the problem.1 Since this time though, research on sion; a uni®ed treatment of damping forces is included as well. The cloth simulation has generally relied on explicit numerical integra- implicit integration method generates a large, unbanded sparse lin- tion (such as Euler's method or Runge-Kutta methods) to advance ear system at each time step which is solved using a modi®ed con- the simulation, or, in the case of of energy minimization, analogous jugate gradient method that simultaneously enforces particles' con- methods such as steepest-descent [3, 10].