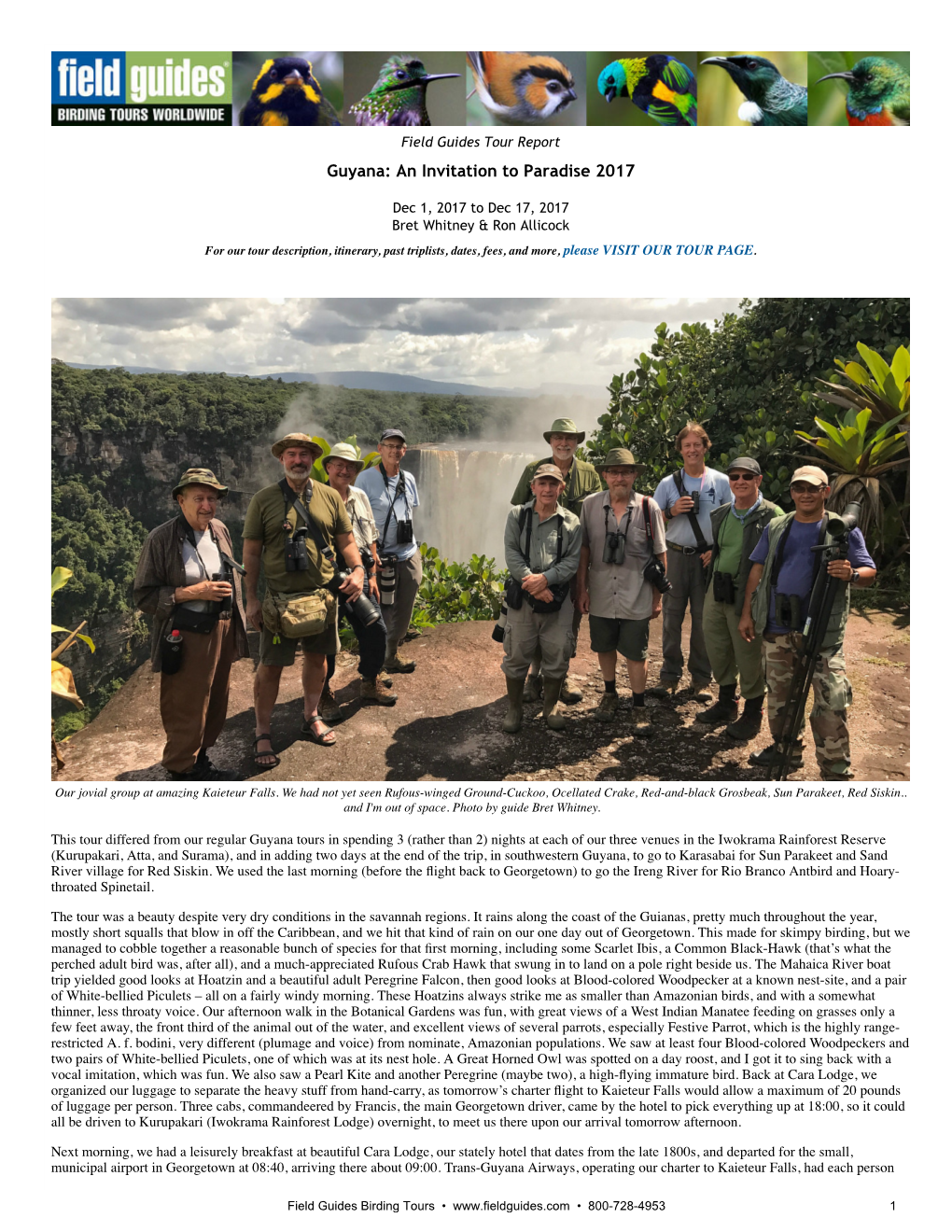

An Invitation to Paradise 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colombia Mega II 1St – 30Th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report

Colombia Mega II 1st – 30th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report Black Manakin by Trevor Ellery Trip Report compiled by tour leader: Trevor Ellery Trip Report – RBL Colombia - Mega II 2016 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top ten birds of the trip as voted for by the Participants: 1. Ocellated Tapaculo 6. Blue-and-yellow Macaw 2. Rainbow-bearded Thornbill 7. Red-ruffed Fruitcrow 3. Multicolored Tanager 8. Sungrebe 4. Fiery Topaz 9. Buffy Helmetcrest 5. Sword-billed Hummingbird 10. White-capped Dipper Tour Summary This was one again a fantastic trip across the length and breadth of the world’s birdiest nation. Highlights were many and included everything from the flashy Fiery Topazes and Guianan Cock-of- the-Rocks of the Mitu lowlands to the spectacular Rainbow-bearded Thornbills and Buffy Helmetcrests of the windswept highlands. In between, we visited just about every type of habitat that it is possible to bird in Colombia and shared many special moments: the diminutive Lanceolated Monklet that perched above us as we sheltered from the rain at the Piha Reserve, the showy Ochre-breasted Antpitta we stumbled across at an antswarm at Las Tangaras Reserve, the Ocellated Tapaculo (voted bird of the trip) that paraded in front of us at Rio Blanco, and the male Vermilion Cardinal, in all his crimson glory, that we enjoyed in the Guajira desert on the final morning of the trip. If you like seeing lots of birds, lots of specialities, lots of endemics and enjoy birding in some of the most stunning scenery on earth, then this trip is pretty unbeatable. -

ON (19) 599-606.Pdf

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 19: 599–606, 2008 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society BODY MASSES OF BIRDS FROM ATLANTIC FOREST REGION, SOUTHEASTERN BRAZIL Iubatã Paula de Faria1 & William Sousa de Paula PPG-Ecologia, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] Massa corpórea de aves da região de Floresta Atlântica, sudeste do Brasil. Key words: Neotropical birds, weight, body mass, tropical rainforest, Brazil. The Brazilian Atlantic forest is one of the In this paper, we present the values of biodiversity hotspots in the world (Myers body masses of birds captured or collected 1988, Myers et al. 2000) with high endemism using mist-nets in 17 localities in the Atlantic of bird species (Cracraft 1985, Myers et al. forest of southeastern Brazil (Table 1), 2000). Nevertheless, there is little information between 2004 and 2007. Data for sites 1, 2, 3, on the avian body masses (weight) for this and 5 were collected in January, April, August, region (Oniki 1981, Dunning 1992, Belton and December 2004; in March and April 2006 1994, Reinert et al. 1996, Sick 1997, Oniki & for sites 4, 6, 7, and 8. Others sites were col- Willis 2001, Bugoni et al. 2002) and for other lected in September 2007. The Atlantic forest Neotropical ecosystems (Fry 1970, Oniki region is composed by two major vegetation 1980, 1990; Dick et al. 1984, Salvador 1988, types: Atlantic rain forest (low to medium ele- 1990; Peris 1990, Dunning 1992, Cavalcanti & vations, = 1000 m); and Atlantic semi-decidu- Marini 1993, Marini et al. 1997, Verea et al. ous forest (usually > 600 m) (Morellato & 1999, Oniki & Willis 1999). -

Robbins Et Al MS-620.Fm

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 18: 339-368, 2007 © The Neotropical Ornithological Societ)' AVIFAUNA OF THE UPPER ESSEQUIBO RIVER AND ACARY MOUNTAINS, SOUTHERN GUYANA Mark B. Robbins\ Michael J. Braun^, Christopher M. Miiensl<y^, Brian K. Schmidt^, Waldyl<e Prince", Nathan H. Rice^ Davis W. Finch^ & Brian J. O'Shea^ ^University of Kansas Natural History Museum & Biodiversity Research Center (KUIVINH), 1345 Jayhawk Boulevard, Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA. E-mail: [email protected] ^Department of Vertebrate Zoology, National Museum of Natural History (USNM), Smithsonian Institution, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA. ^Smithsonian Institution, Division of Birds, PO Box 37012, Washington DC, 20013-7012, USA. "Iwokrama International Centre, PO Box 10630, 77 High Street, Kingston, Georgetown, Guyana. ^Academy of Natural Sciences (ANSP), 1900 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19103, USA. ^91 South Road, East Kingston, New Hampshire 03827, USA. '^Department of Biological Sciences and Museum of Natural Science, 119 Foster Hall, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70803, USA. Resumen. — Avifauna del alto Rio Essequibo y la Sierra de Acary, en el sur de Guyana. — Realizamos inventarios intensivos durante dos temporadas 5' varias visitas de menor duracion en el alto Rio Essequibo, en el extremo sur de Guyana, en una zona que esta entre las menos impactadas per humanos en el planeta. En total, registramos 441 especies de aves, incluyendo los primeros registros de 12 especies para el pals. Para otras cuatro especies, colectamos los primeros especimenes del pais. Presentamos informacion acerca de abundancia relativa, preferencias de habitat y estatus reproductivo. La Hsta de especies para esta region es mayor que la de otro sitio intensamente estudiado al norte de Manaos, en Brazil, pero menor que la de la Selva Iwokrama en el centre de Guyana. -

Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018

Field Guides Tour Report Peru's Magnetic North: Spatuletails, Owlet Lodge & More 2018 Jun 23, 2018 to Jul 5, 2018 Dan Lane & Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The name of this tour highlights a few of the spectacular birds that make their homes in Peru's northern regions, and we saw these, and many more! This might have been called the "Antpittas and More" tour, since we had such great views of several of these formerly hard-to-see species. This Ochre-fronted Antpitta was one; she put on a fantastic display for us! Photo by participant Linda Rudolph. The eastern foothills of Andes of northern Peru are one of those special places on the planet… especially if you’re a fan of birds! The region is characterized by pockets of white sand forest at higher elevations than elsewhere in most of western South America. This translates into endemism, and hence our interest in the region! Of course, the region is famous for the award-winning Marvelous Spatuletail, which is actually not related to the white sand phenomenon, but rather to the Utcubamba valley and its rainshadow habitats (an arm of the dry Marañon valley region of endemism). The white sand endemics actually span areas on both sides of the Marañon valley and include several species described to science only since about 1976! The most famous of this collection is the diminutive Long-whiskered Owlet (described 1977), but also includes Cinnamon Screech-Owl (described 1986), Royal Sunangel (described 1979), Cinnamon-breasted Tody-Tyrant (described 1979), Lulu’s Tody-Flycatcher (described 2001), Chestnut Antpitta (described 1987), Ochre-fronted Antpitta (described 1983), and Bar-winged Wood-Wren (described 1977). -

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa; with Southern Extension a Tropical Birding Set Departure

ETHIOPIA: Birding the Roof of Africa; with Southern Extension A Tropical Birding Set Departure February 7 – March 1, 2010 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos taken by Ken Behrens during this trip ORIENTATION I have chosen to use a different format for this trip report. First, comes a general introduction to Ethiopia. The text of this section is largely drawn from the recently published Birding Ethiopia, authored by Keith Barnes, Christian, Boix and I. For more information on the book, check out http://www.lynxeds.com/product/birding-ethiopia. After the country introduction comes a summary of the highlights of this tour. Next comes a day-by-day itinerary. Finally, there is an annotated bird list and a mammal list. ETHIOPIA INTRODUCTION Many people imagine Ethiopia as a flat, famine- ridden desert, but this is far from the case. Ethiopia is remarkably diverse, and unexpectedly lush. This is the ʻroof of Africaʼ, holding the continentʼs largest and most contiguous mountain ranges, and some of its tallest peaks. Cleaving the mountains is the Great Rift Valley, which is dotted with beautiful lakes. Towards the borders of the country lie stretches of dry scrub that are more like the desert most people imagine. But even in this arid savanna, diversity is high, and the desert explodes into verdure during the rainy season. The diversity of Ethiopiaʼs landscapes supports a parallel diversity of birds and other wildlife, and although birds are the focus of our tour, there is much more to the country. Ethiopia is the only country in Africa that was never systematically colonized, and Rueppell’s Robin-Chat, a bird of the Ethiopian mountains. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version Available for Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Beatriz de Aquino Ribeiro - Bióloga - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) Designation date Site Reference Number 99136-0940. Antonio Lisboa - Geógrafo - MSc. Biogeografia - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) 99137-1192. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade - ICMBio Rua Alfredo Cruz, 283, Centro, Boa Vista -RR. CEP: 69.301-140 2. -

Southern Wing-Banded Antbird, Myrmornis Torquata Myrmornithinae

Thamnophilidae: Antbirds, Species Tree I Northern Wing-banded Antbird, Myrmornis stictoptera ⋆Southern Wing-banded Antbird, Myrmornis torquata ⋆ Myrmornithinae Spot-winged Antshrike, Pygiptila stellaris Russet Antshrike, Thamnistes anabatinus Rufescent Antshrike, Thamnistes rufescens Guianan Rufous-rumped Antwren, Euchrepomis guianensus ⋆Western Rufous-rumped Antwren, Euchrepomis callinota Euchrepomidinae Yellow-rumped Antwren, Euchrepomis sharpei Ash-winged Antwren, Euchrepomis spodioptila Chestnut-shouldered Antwren, Euchrepomis humeralis ⋆Stripe-backed Antbird, Myrmorchilus strigilatus ⋆Dot-winged Antwren, Microrhopias quixensis ⋆Yapacana Antbird, Aprositornis disjuncta ⋆Black-throated Antbird, Myrmophylax atrothorax ⋆Gray-bellied Antbird, Ammonastes pelzelni MICRORHOPIINI ⋆Recurve-billed Bushbird, Neoctantes alixii ⋆Black Bushbird, Neoctantes niger Rondonia Bushbird, Neoctantes atrogularis Checker-throated Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla fulviventris Western Ornate Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla ornata Eastern Ornate Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla hoffmannsi Rufous-tailed Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla erythrura White-eyed Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla leucophthalma Brown-bellied Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla gutturalis Foothill Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla spodionota Madeira Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla amazonica Roosevelt Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla dentei Negro Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla pyrrhonota Brown-backed Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla fjeldsaai ⋆Napo Stipplethroat, Epinecrophylla haematonota ⋆Streak-capped Antwren, Terenura -

Sun Parakeet Birding Tour

Leon Moore Nature Experience – Sun Parakeet Birding Tour Guyana is a small English-speaking country located on the Atlantic Coast of South America, east of Venezuela and west of Suriname. Deserving of its reputation as one of the top birding and wildlife destinations in South America, Guyana’s pristine habitats stretch from the protected shell beach and mangrove forest along the northern coast, across the vast untouched rainforest of the interior, to the wide open savannah of the Rupununi in the south. Guyana hosts more than 850 different species of birds covering over 70 families. Perhaps the biggest attraction is the 45+ Guianan Shield endemic species that are more easily seen here than any other country in South America. These sought-after near-endemic species include everything from the ridiculous to the sublime - from the outrageous Capuchinbird with a bizarre voice unlike any other avian species to the unbelievably stunning Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock. While the majestic Harpy Eagle is on everyone’s “must-see” list, other species are not to be overlooked, such as Rufous-throated, White-plumed and Wing-barred Antbirds, Gray-winged Trumpeter, Rufous-winged Ground Cuckoo, Blood-colored Woodpecker, Rufous Crab-Hawk, Guianan Red-Cotinga, White-winged Potoo, Black Curassow, Sun Parakeet, Red Siskin, Rio-Branco Antbird, and the Dusky Purpletuft. These are just a few of the many spectacular birding highlights that can be seen in this amazing country. Not only is Guyana a remarkable birding destination, but it also offers tourists the opportunity to observe many other unique fauna. The elusive Jaguar can sometimes be seen along trails and roadways. -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

Lista Das Aves Do Brasil

90 Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos content / conteÚDO Abstract ............................. 91 Charadriiformes ......................121 Scleruridae .............187 Charadriidae .........121 Dendrocolaptidae ...188 Introduction ........................ 92 Haematopodidae ...121 Xenopidae .............. 195 Methods ................................ 92 Recurvirostridae ....122 Furnariidae ............. 195 Burhinidae ............122 Tyrannides .......................203 Results ................................... 94 Chionidae .............122 Pipridae ..................203 Scolopacidae .........122 Oxyruncidae ..........206 Discussion ............................. 94 Thinocoridae .........124 Onychorhynchidae 206 Checklist of birds of Brazil 96 Jacanidae ...............124 Tityridae ................207 Rheiformes .............................. 96 Rostratulidae .........124 Cotingidae .............209 Tinamiformes .......................... 96 Glareolidae ............124 Pipritidae ............... 211 Anseriformes ........................... 98 Stercorariidae ........125 Platyrinchidae......... 211 Anhimidae ............ 98 Laridae ..................125 Tachurisidae ...........212 Anatidae ................ 98 Sternidae ...............126 Rhynchocyclidae ....212 Galliformes ..............................100 Rynchopidae .........127 Tyrannidae ............. 218 Cracidae ................100 Columbiformes -

List of References for Avian Distributional Database

List of references for avian distributional database Aastrup,P. and Boertmann,D. (2009.) Biologiske beskyttelsesområder i nationalparkområdet, Nord- og Østgrønland. Faglig rapport fra DMU. Aarhus Universitet. Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser. Pp. 1-92. Accordi,I.A. and Barcellos,A. (2006). Composição da avifauna em oito áreas úmidas da Bacia Hidrográfica do Lago Guaíba, Rio Grande do Sul. Revista Brasileira de Ornitologia. 14:(2): 101-115. Accordi,I.A. (2002). New records of the Sickle-winged Nightjar, Eleothreptus anomalus (Caprimulgidae), from a Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil wetland. Ararajuba. 10:(2): 227-230. Acosta,J.C. and Murúa,F. (2001). Inventario de la avifauna del parque natural Ischigualasto, San Juan, Argentina. Nótulas Faunísticas. 3: 1-4. Adams,M.P., Cooper,J.H., and Collar,N.J. (2003). Extinct and endangered ('E&E') birds: a proposed list for collection catalogues. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 123A: 338-354. Agnolin,F.L. (2009). Sobre en complejo Aratinga mitrata (Psittaciformes: Psittacidae) en el noroeste Argentino. Comentarios sistemáticos. Nótulas Faunísticas - Segunda Serie. 31: 1-5. Ahlström,P. and Mild,K. (2003.) Pipits & wagtails of Europe, Asia and North America. Identification and systematics. Christopher Helm. London, UK. Pp. 1-496. Akinpelu,A.I. (1994). Breeding seasons of three estrildid species in Ife-Ife, Nigeria. Malimbus. 16:(2): 94-99. Akinpelu,A.I. (1994). Moult and weight cycles in two species of Lonchura in Ife-Ife, Nigeria. Malimbus . 16:(2): 88-93. Aleixo,A. (1997). Composition of mixed-species bird flocks and abundance of flocking species in a semideciduous forest of southeastern Brazil. Ararajuba. 5:(1): 11-18. -

Great Rivers of the Amazon III: Mamirauá, Amanã, and Tefé 2019

Field Guides Tour Report Great Rivers of the Amazon III: Mamirauá, Amanã, and Tefé 2019 Dec 2, 2019 to Dec 16, 2019 Bret Whitney & Micah Riegner For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. The White Uakari alone is a reason to visit this part of Amazonia. With its striking red face, purple eyeshadow and fluffy white fur, it's gotta be one of the most outlandish of all Neotropical primates. We had an amazing time watching a troop right above us at Mamiraua. Photo by Micah Riegner. Establishing a new tour in Amazonia where no birders go is always thrilling—you just never know what you’re going to find up the next igarape (creek), what the next feeding flock will bring, or night outing might yield. So, in perpetuating the Field Guides tradition of going to new exciting places, Bret and I visited Reserva Amana and FLONA Tefe back in June. These two enormous swaths of protected forest in the heart of Amazonia had never been visited by a tour group, so we had some ground-truthing to do before the tour. This involved spending hours in a voadeira (open-top metal boat with outboard motor) to reach the isolated communities within the reserves, meeting with the local people and explaining what bird-watching is all about and checking out the trails they had cleared in anticipation of our arrival. Our scouting was fruitful, and we are pleased to announce a successful first run of the tour! There were numerous highlights, from seeing between 1,500 and 2,000 Sand-colored Nighthawks dusting the treetops like snow at Amana to watching Margays almost getting into a cat fight in the canopy at Mamiraua and the band of White Uakaris with their intimidating red faces.