9. St Ives, Hunts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DISSERTATION-Submission Reformatted

The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 By Robert Lee Harkins A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor David Bates Fall 2013 © Robert Lee Harkins 2013 All Rights Reserved 1 Abstract The Dilemma of Obedience: Persecution, Dissimulation, and Memory in Early Modern England, 1553-1603 by Robert Lee Harkins Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Ethan Shagan, Chair This study examines the problem of religious and political obedience in early modern England. Drawing upon extensive manuscript research, it focuses on the reign of Mary I (1553-1558), when the official return to Roman Catholicism was accompanied by the prosecution of Protestants for heresy, and the reign of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), when the state religion again shifted to Protestantism. I argue that the cognitive dissonance created by these seesaw changes of official doctrine necessitated a society in which religious mutability became standard operating procedure. For most early modern men and women it was impossible to navigate between the competing and contradictory dictates of Tudor religion and politics without conforming, dissimulating, or changing important points of conscience and belief. Although early modern theologians and polemicists widely declared religious conformists to be shameless apostates, when we examine specific cases in context it becomes apparent that most individuals found ways to positively rationalize and justify their respective actions. This fraught history continued to have long-term effects on England’s religious, political, and intellectual culture. -

Barnwell Priory 1

20 OCTOBER 2014 BARNWELL PRIORY 1 Release date Version notes Who Current version: H1-Barnwell-2014-1 20/10/14 Original version RS, NK Previous versions: ———— This text is made available through the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs License; additional terms may apply Authors for attribution statement: Charters of William II and Henry I Project Richard Sharpe, Faculty of History, University of Oxford Nicholas Karn, University of Southampton BARNWELL PRIORY Augustinian Priory of St Giles & St Andrew County of Cambridge : Diocese of Ely Founded 1092 in St Giles’s church, Cambridge; moved to Barnwell 1112 Augustinian canons were first brought to Cambridge under the auspices of Picot, sheriff of Cambridge, and his wife Hugolina, in fulfilment of a vow that Hugolina had made when ill (Liber memorandorum, I 3 p. 38). Their foundation was made in the church of St Giles, close to Picot’s base in Cambridge castle and across the river from most of the developing town. According to the Barnwell chronicle, this foundation for six canons was made with the assistance and assent of both Remigius, bishop of Lincoln (died 8 May 1092), and Anselm, archbishop of Canterbury (nominated March 1093) (Liber memorandorum, I 4 p. 39). The date is given as 1092 (ib. I 18 p. 46). Anselm’s involvement was perhaps an enhancement by the chronicler. At the death soon afterwards of Picot and Hugolina, this inchoate establishment fell into the care of their son Robert, who was disgraced for plotting against King Henry; his forfeit possessions were given by the king to Pain Peverel (ib. -

Incidents in My Life and Ministry

This is a re-creation of the original – see page 2 – and please note that the headings on the contents page 3 are hyperlinks INCIDENTS IN MY LIFE AND MINISTRY BY CANON A. G. HUNTER Some time Vicar of Christ Church, Epsom, Rural Dean of Leatherhead, and Hon. Canon in Winchester Cathedral. PUBLISHED BY BIRCH & WHITTINGTON, 10, STATION ROAD, EPSOM, SURREY. 1935. Price Two Shillings Net. DEDICATION. To my dear old Epsom friends I dedicate this little book. A. G. H. Transcriber’s note This small book (of some 100 octavo pages in the 1935 original) has long been out of print. To provide a more accessible source for local and other historians, the present text has been scanned in from an original held by Epsom & Ewell Borough Council’s local history museum at Bourne Hall, Ewell. While it reflects the typography and layout of the original, it does not – as is obvious from the different page count – purport to be a facsimile. Archer George Hunter (pictured here in about 1908) was born on 12 November 1850. As the title page indicates, he was among other things Vicar of Christ Church, Epsom Common. Appointed in 1881 to succeed the first Vicar, the Revd George Willes (who served from the parish’s foundation in 1876) he led the parish for 30 years until his retirement in 1911 at the age of 60. In 1906, he was appointed as Rural Dean of Leatherhead, alongside (as is usual) his parish duties. Less usually, he continued as Rural Dean – perhaps even more actively – after standing down from the parish, retiring from that in 1925 at the age of 75. -

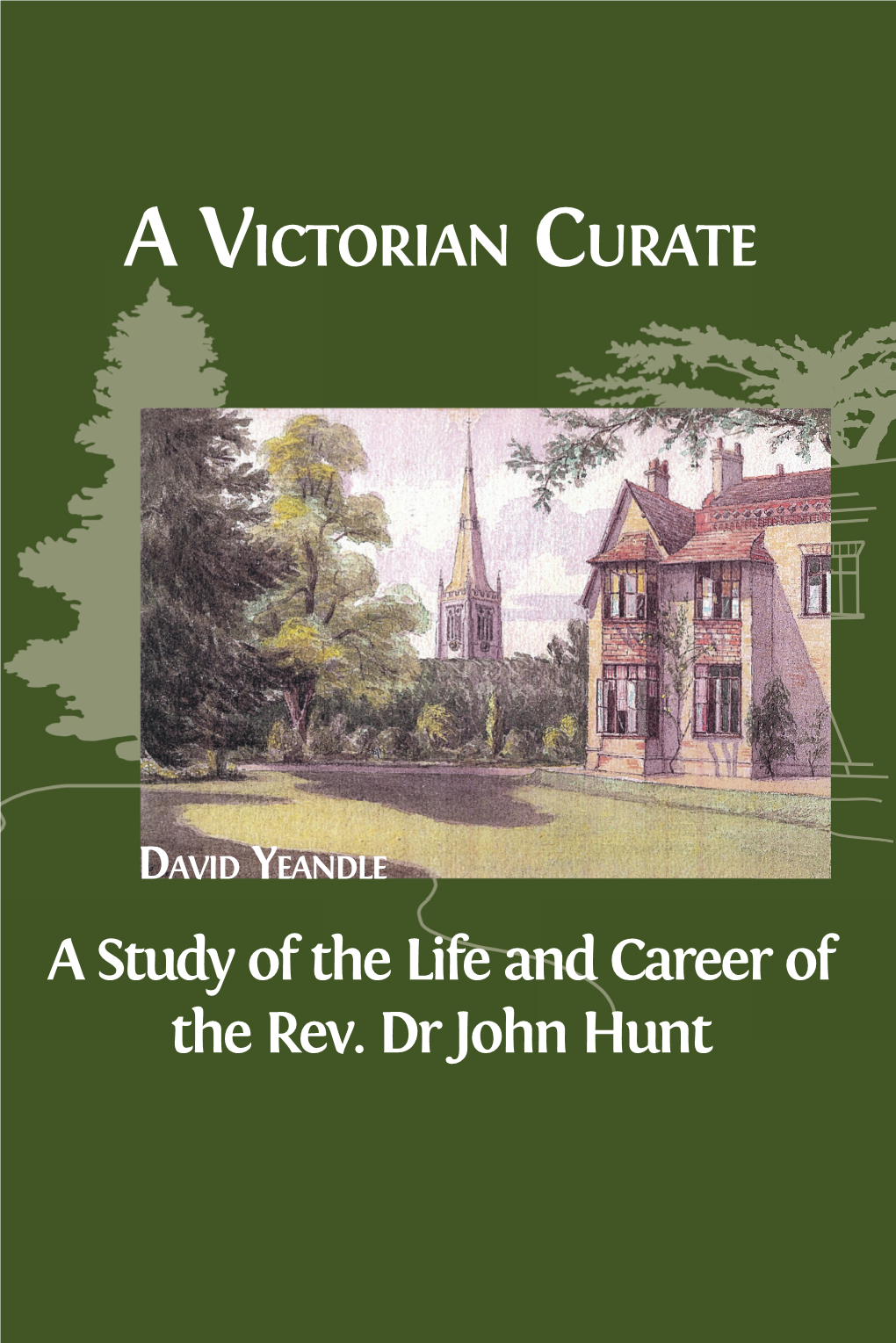

A Victorian Curate: a Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. Dr John Hunt

D A Victorian Curate A Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. Dr John Hunt DAVID YEANDLE AVID The Rev. Dr John Hunt (1827-1907) was not a typical clergyman in the Victorian Church of England. He was Sco� sh, of lowly birth, and lacking both social Y ICTORIAN URATE EANDLE A V C connec� ons and private means. He was also a wi� y and fl uent intellectual, whose publica� ons stood alongside the most eminent of his peers during a period when theology was being redefi ned in the light of Darwin’s Origin of Species and other radical scien� fi c advances. Hunt a� racted notoriety and confl ict as well as admira� on and respect: he was A V the subject of ar� cles in Punch and in the wider press concerning his clandes� ne dissec� on of a foetus in the crypt of a City church, while his Essay on Pantheism was proscribed by the Roman Catholic Church. He had many skirmishes with incumbents, both evangelical and catholic, and was dismissed from several of his curacies. ICTORIAN This book analyses his career in London and St Ives (Cambs.) through the lens of his autobiographical narra� ve, Clergymen Made Scarce (1867). David Yeandle has examined a li� le-known copy of the text that includes manuscript annota� ons by Eliza Hunt, the wife of the author, which off er unique insight into the many C anonymous and pseudonymous references in the text. URATE A Victorian Curate: A Study of the Life and Career of the Rev. -

Newsletter HIB Autumn 2020

BEDFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION HISTORY IN BEDFORDSHIRE VOLUME 9, NO 1, AUTUMN 2020 The Association’s 27th Year www.bedfordshire-lha.org.uk Contents Articles: Sister Fanny (1836–1907): Pioneer Church of England deaconess in Bedford: STUART ANTROBUS ~ page 2 The Lancastria tragedy and Private Ronald Charles Pates: LINDA S AYRES ~ page 16 Notes from the Beds Mercury: Wild Life ~ page 20 Peter Gilman, artist: TED MARTIN ~ page 21 Society Bookshelf ~ page 23 History in Bedfordshire is published by the BEDFORDSHIRE LOCAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION www.bedfordshire-lha.org.uk For HIB: Editor: Ted Martin, 2A The Leys, Langford, Beds SG18 9RS Telephone: 01462 701096. E-mail: [email protected] For BLHA: Secretary: Clive Makin, 32 Grange Road, Barton Le Clay, Bedford MK45 4RE: Telephone: 01582 655785 Contributions are very welcome and needed: please telephone or e-mail the Editor before sending any material. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2020 BLHA Bedfordshire Local History Association and contributors. ISSN 0968–9761 1 Sister Fanny (1836–1907) Pioneer Church of England deaconess in Bedford* Fanny Elizabeth Eagles was born in Bedford on 10 December 1836 at the family home in Harpur Place1 the youngest of three children. Her father was Ezra Eagles (1803–1865),2 solicitor, Coroner and Clerk of the Peace for the County, and his wife, Elizabeth Halfhead (1804–1866).3 Such was Fanny’s delicate state of health as an infant, she was baptised privately, and afterwards ‘received into the church’ at St Peter’s. Fanny received her first communion at her confirmation in 1852 at Holy Trinity Church, Bedford.4 She is said to have played the organ there. -

Hampshire Bibliography

127 A SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO HAMPSHIRE BIBLIOGRAPHY. BY REV. R. G. DAVIS. The Bibliography of Hampshire was first attempted by the Rev. Sir W. H. Cope, Bart., who compiled and printed " A LIST OF BOOKS RELATING TO HAMPSHIRE, IN THE LIBRARY AT BRAMSHILL." 8VO. 1879. (Not Published.) The entire collection, with many volumes of Hampshire Views and Illustrations, was bequeathed by Sir W. Cope to the Hartley Institution, mainly through the influence of the late Mr. T. W. Shore, and' on the death of the donor in 1892 was removed to Southampton. The List compiled by the original owner being " privately printed' became very rare, and was necessarily incomplete. In 1891 a much fuller and more accurate Bibliography was published with the following title:—" BIBLIOTHECA HANTONIENSIS, a List of Books relating, to Hampshire, including Magazine References, &c, &c, by H. M. Gilbert and the Rev. G. N. Godwin, with a List of Hampshire Newspapers, by F. E. Edwards. Southampton. 1891. The List given in the above publication was considerably augmented by a SUPPLEMENTARY HAMPSHIRE BIBLIOGRAPHY, compiled by the Rev. Sumner Wilson, Rector of Preston Candover, printed in the PAPERS AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HAMPSHIRE FIELD CLUB. Vol. III., p. 303. A further addition to the subject is here offered with a view to rendering the Bibliography of Hants as complete as possible. Publications referring to the Isle of Wight are not comprised in this List. 128 FIRST PORTION.—Letters A to K. ACT for widening the roads from the end of Stanbridge Lane, near a barn in the Parish of Romsey. -

DMH Christmas Lights Book of Memories

Moy Abberley Rose Abbey Barry & Dorothy Abbotts Josephine Abel Josie Abell Absent Family & Friends Absent Friends David Ackley Andrew Adam Alf Adams Carol Adams Carol Ann Adams George & Margaret Adams Jean Adams John Adams Keith Roland Adams Lydia Adams Michelle Adams Pauline Ann Adams Thomas & Mary Adams Valerie Adams John Adamson Tina Adamson Frederick Aggus Kitty Aggus Bob Ainslie Albert Beryl Alcock Brenda Alcock Edith M Alcock Frederick Alcock Graham Alcock Harry Alcock Jean Alcock Jeannette Alcock John & Muriel Alcock Kath & Tom Alcock Lily Alcock Mr & Mrs T Alcock Nora Alcock Ronald Alcock Arthur Alcock Snr Sylvia Alcock Tommy Alcock William Alcock Gwen Aldersea Aldridge Family All Loved Ones All Relatives Dereck Allan Henry Allbutt Rose Allbutt Denis Allcock Reg Allcock Alf Allebon Edith & Kenneth Allebon Adelaide Allen Barry Allen Cissie Allen Dave Allen David Allen The Allen Family George Allen Graham Allen Graham E Allen Joan Allen John Allen Keith Allen Mick Allen Paula J Allen Rachel Louise Allen Roy Allen Mark Andrew Allingham Albert Allman Craig Allman Ethel Allman John Allman Ken Allman Marilyn Allman Millicent Allman Stephen Allon Ron Allott Bill Amison Doris Amison Empsie & Jim Amison The Amison Family Fred, Mary & Ann Amison Joseph, Gordon & Gladys Amison Mary Amison Nancy Amison Raymond Amison Shaun Amison Stan, Janet & Steven Amison Tony & Sylvia Amison Ann Amos Ivy Amos Alice & Bob Anderson Dennis Anderson Dennis John Anderson Nora Anderson Anita Nannie Annie Derek Ansell Teresa Ansell Anthony & Dave John Anthony -

The Fathers in the English Reformation

Durham E-Theses The study of the fathers in the Anglican tradition 16th-19th centuries Middleton, Thomas Arthur How to cite: Middleton, Thomas Arthur (1995) The study of the fathers in the Anglican tradition 16th-19th centuries, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5328/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ir-ji.r,;;s.;','is THE STUDY OF THE FATHERS IN THE ANGLICAN TRADITION iiiilli 16TH-19TH CENTURIES iliii ii^wiiiiiBiiiiiii! lililiiiiliiiiiln mom ARTHUR MIDDLETON The Study of the Fathers in The Anglican Tradition 16th-19th Centuries The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be pubhshed without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. By The Revd. Thomas Arthur Middleton Rector of Boldon 1995 M.Litt., Thesis Presented to UieFaculty of Arts 1MAY 1996 University of Durham Department of Theology Acknowledgements The author expresses his thanks to the Diocese of Durham for the giving of a grant to enable this research to be done and submitted. -

Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 55, No. 4, October 2004. f 2004 Cambridge University Press 654 DOI: 10.1017/S0022046904001502 Printed in the United Kingdom Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England by PETER SHERLOCK The Reformation simultaneously transformed the identity and role of bishops in the Church of England, and the function of monuments to the dead. This article considers the extent to which tombs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bishops represented a set of episcopal ideals distinct from those conveyed by the monuments of earlier bishops on the one hand and contemporary laity and clergy on the other. It argues that in death bishops were increasingly undifferentiated from other groups such as the gentry in the dress, posture, location and inscriptions of their monuments. As a result of the inherent tension between tradition and reform which surrounded both bishops and tombs, episcopal monuments were unsuccessful as a means of enhancing the status or preserving the memory and teachings of their subjects in the wake of the Reformation. etween 1400 and 1700, some 466 bishops held office in England and Wales, for anything from a few months to several decades.1 The B majority died peacefully in their beds, some fading into relative obscurity. Others, such as Richard Scrope, Thomas Cranmer and William Laud, were executed for treason or burned for heresy in one reign yet became revered as saints, heroes or martyrs in another. Throughout these three centuries bishops played key roles in the politics of both Church and PRO=Public Record Office; TNA=The National Archives I would like to thank Craig D’Alton, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Ralph Houlbrooke, Judith Maltby, Keith Thomas and the anonymous reader for this JOURNAL for their comments on this article. -

UNKNOWN ADDRESSES of TRINITY OLD BOYS G (As of January 2013) T

O T S U UNKNOWN ADDRESSES OF TRINITY OLD BOYS G (As of January 2013) T M M E N U T N E U Do you know of contact details for these Old Boys with whom we have lost contact? S M M U UL ILI If you do please click here to let us know their whereabouts. Thank you. TAE CONS John Adams 1925 David Garnsey 1927 Colin Fredericks 1929 Harold Barnes 1925 Rowland Gittoes 1927 Eric Gordon 1929 William Barton 1925 Jack Greenwood 1927 Ross Gordon 1929 Bruce Bellamy 1925 Kenwyn Hall 1927 Leslie Gramleese 1929 Robert Butler 1925 Henry Henlein 1927 Walter Green 1929 Charles Carr 1925 William Holford 1927 Frank Gribble 1929 Tom Carter 1925 Henry King 1927 Ralph Harper 1929 Richard Christian 1925 William Kinsela 1927 Stanley Hean 1929 Gordon Finlayson 1925 Carl Lassau 1927 Douglas Heighway 1929 Neil Greig 1925 Russell Matthews 1927 Jacob Hyman 1929 William Henderson 1925 Geoffrey Parr 1927 Jack Hyman 1929 William Higstrim 1925 Allan Pendlebury 1927 Frank Johnson 1929 Alan Hoad 1925 Arthur Reeves 1927 David Knox 1929 Frederick Huet 1925 Hugh Rothwell 1927 George Lee 1929 Frank Mansell 1925 George Searley 1927 Raymond Maclean 1929 Charles McPhee 1925 William Shelley 1927 John Marchant 1929 Clifford Mitchell 1925 Richard Stokes 1927 Lesley Murray 1929 Ewen Mitchell 1925 Ronald Tildesley 1927 Mansergh Parker 1929 John Newton 1925 Jack Walker 1927 John Parker 1929 Joseph Painter 1925 Ivo Bolton 1928 John Price 1929 Leslie Randle 1925 Cyril Cheney 1928 Enoch Rees 1929 Leslie Scutts 1925 Noel Christian 1928 Brian Roche 1929 Charles Simons 1925 Norman Cole 1928 Wilfred -

Light up a Life 2019 BOOK of MEMORIES

Light Up A Life 2019 BOOK OF MEMORIES ANY NAMES DEDICATED FROM 25TH NOVEMBER ONWARDS WILL APPEAR ALPHABETICALLY AT THE END OF THE BOOK Douglas Macmillan Hospice 1071613 Moy Abberley Rose Abbey Dennis Henry Abbott Christopher Bruce Abbotts Dorothy May Abbotts Dotty & Barry Abbotts Harold Abbotts Josie Abell Absent Family & Friends David Ackley Ada & Cathy Albert Adams Alf Adams Carol Adams Christopher Adams Dennis Adams George & Margaret Adams John & Ethel Adams Keith Roland Adams Leslie Adams Lucy Adams Lydia Adams Mary Adams Pauline Ann Adams Tom & Mary Adams Valerie Adams Jack Adamson John Adamson Tina Adamson Frederick Aggus Kitty Aggus Eunice Ainsworth Bernard & Cecilia Akers Albert Barbara Alcock Barry James Alcock Beryl Alcock Brenda Alcock Dorothy Alcock Edith Alcock Emmie Alcock Frederick Alcock Harry Alcock Jean Alcock John & Muriel Alcock Joyce Alcock Kathleen Alcock Ken Alcock Lily Alcock Mildred Alcock Ronald Alcock Roy William Alcock Arthur Alcock Snr Sylvia Alcock Tom & Kath Alcock Tommy Alcock William Alcock Gwen Aldersea Alec, Wendy & Peter Marie Alexander Elsie Alford (nee Wright) All Family & Friends All Loved Ones Joseph Allbutt Rose & Henry Allbutt Denis Allcock Peter Allcock Reg Allcock Pauline & John Allday Alf Allebon Adelaide Allen Barry Allen Cissie Allen David Allen Doris Allen Allen Family George Allen Graham Allen Janet Allen John Allen Keith Allen Mary Allen Nola Allen Peter Allen Rachel Louise Allen Yvonne Allen Mark Andrew Allingham Craig Allman Ethel Allman Stephen Allon Ron Allott Roy Almond Marion Ambrose -

The Virginia Law Revision of 1748-49

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1968 The Virginia Law Revision of 1748-49 Gwenda Morgan College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Morgan, Gwenda, "The Virginia Law Revision of 1748-49" (1968). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539624649. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-29gr-tk94 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE VIRGINIA LAW REVISION OF 1748-49 A Theei-s Presented to The Faeulty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements? for the Degree of Master of Art© By Gwenda Morgan 1968 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial, fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts ^ YTlani a Author Approved, August 1968 W/1/^ ies McCord, Ph.D. George Reese, Ph.D. •= ? & Thaddeus W. Tate, Pfc^D. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS X wish to extend my thanks to Dr* T*W# Tate for his assistance and encouragement in preparing this thesis* I must also thank the staff of the Sesearch library of Colonial Williamsburg* Inc*, for .the use of their facilities*- The staff of the Public Becord Office*, the Boyal Society of Arts* the Virginia Historical Society* the Virginia State library* and the Alderman Library proved courteous and helpful at all times* til LIST OF CONTENTS Fags ackkowisdoekehtb i u ABBEEVIATIOHS ...