Inspection Report Chilwell Comprehensive School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pupils with Special Educational Needs (SEN) in Nottinghamshire Schools by the School They Attend Data Source: Jan 2018 School Census

Pupils with special educational needs (SEN) in Nottinghamshire schools by the school they attend Data source: Jan 2018 school census DfE ID Name District Phase SEN Pupils 2788 Abbey Gates Primary School Gedling Primary 7 3797 Abbey Hill Primary School Ashfield Primary 39 3297 Abbey Primary School Mansfield Primary 33 2571 Abbey Road Primary School Rushcliffe Primary 17 2301 Albany Infant and Nursery School Broxtowe Primary 8 2300 Albany Junior School Broxtowe Primary 9 2302 Alderman Pounder Infant School Broxtowe Primary 24 4117 Alderman White School Broxtowe Secondary 58 3018 All Hallows CofE Primary School Gedling Primary 21 4756 All Saints Catholic Voluntary Academy Mansfield Secondary 99 3774 All Saints CofE Infants School Ashfield Primary 9 3539 All Saints Primary School Newark Primary x 2010 Annesley Primary and Nursery School Ashfield Primary 29 3511 Archbishop Cranmer Church of England Academy Rushcliffe Primary 5 2014 Arnbrook Primary School Gedling Primary 29 2200 Arno Vale Junior School Gedling Primary 8 4091 Arnold Hill Academy Gedling Secondary 89 2916 Arnold Mill Primary School Gedling Primary 61 2942 Arnold View Primary and Nursery School Gedling Primary 35 7023 Ash Lea School Rushcliffe Special 74 4009 Ashfield School Ashfield Secondary 291 3782 Asquith Primary and Nursery School Mansfield Primary 52 3783 Awsworth Primary School Broxtowe Primary 54 2436 Bagthorpe Primary School Ashfield Primary x 2317 Banks Road Infant School Broxtowe Primary 18 2921 Barnby Road Academy Primary & Nursery School Newark Primary 71 2464 Beardall -

Women Pass It on – July 14Th 2016

Women Pass it On – July 14th 2016 ESRC funded event at the University of Nottingham Name School Rachel Davie All Saints' Catholic Voluntary Academy, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire Ruth Farrall All Saints' Catholic Voluntary Academy, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire Emily Dalton Arnold Hill Academy, Arnold, Nottinghamshire Ella Strawbridge Arnold Hill Academy, Arnold, Nottinghamshire Ruadh Duggan Carlton le Willows Academy , Gedling, Nottinghamshire Jo Simpson Carlton le Willows Academy, Gedling, Nottinghamshire Lucy Smith Chilwell School, Beeston, Nottingham Sarah Williams Chilwell School, Beeston, Nottingham Lorraine Swan Djanogly City Academy, Nottingham Kathy Hardy East Leake Academy, Loughborough Shan Tait Kimberley School Janet Brashaw Meden School, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire Jenny Brown Nottingham Free School, Nottingham Janet Sheriff Prince Henry's Grammar School Charlotte Oldfield Quarrydale Academy, Sutton-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire Tina Barraclough Rushcliffe School, West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire Ruth Frost Rushcliffe School, West Bridgford, Nottinghamshire Catherine Gordon Selston High School, Selston, Nottinghamshire Cara Walker Selston High School, Selston, Nottinghamshire Lisa Floate The Bramcote School, Bramcote, Nottingham Heidi Gale The Bramcote School, Bramcote, Nottingham Natalie Aveyard The Brunts Academy, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire Dawn Chivers The Brunts Academy, Mansfield, Nottinghamshire Helen Braithwaite The Elizabethan Academy, Retford, Nottinghamshire Christine Horrocks The Elizabethan Academy, Retford, Nottinghamshire Jo Eldridge The Fernwood School, Nottingham Tracy Rees The Fernwood School, Nottingham Kat Kerry The Manor Academy, Mansfield Woodhouse, Nottinghamshire Donna Trusler The Manor Academy, Mansfield Woodhouse, Nottinghamshire Caroline Saxelby Walton Girls' High School . -

Nottinghamshire County Council’S Computerized Distance Measuring Software

Secondary Schools Nottinghamshire For Nottinghamshire community schools, the standard admission oversubscription criteria are detailed in the Admissions to schools: guide for parents. The application breakdown summary at the back of this document is based on information on national offer day 3 March 2014. For academy, foundation and voluntary aided schools which were oversubscribed in Year 7 for 2014/2015 it is not possible to list the criterion under which each application was granted or refused as the criteria for each of these schools is different and is applied by the individual admission authority. For details of allocation of places, please contact the school for further information. All school information is correct at the time of print (July 2014) but is subject to change. Linked Catholic Secondary schools outside of Nottinghamshire There are two Catholic secondary schools outside of Nottinghamshire which are linked to Nottinghamshire primary schools. For information on their oversubscription criteria, please contact the school or the relevant Local Authority for details Doncaster Local Authority St Joseph’s Catholic (Aided) Primary School, Retford and St Patrick’s Catholic (Aided) Primary, Harworth are linked to the McAuley Catholic High School, Specialist College for the Performing Arts, Cantley Lane, Doncaster, South Yorkshire - 01302 537396 www.mcauley.doncaster.sch.uk Derbyshire Local Authority Priory Catholic (Aided) Primary, Eastwood is linked to Saint John Houghton Catholic School, A Specialist Science College, Abbot Road, -

Royal Air Force Visits to Schools

Location Location Name Description Date Location Address/Venue Town/City Postcode NE1 - AFCO Newcas Ferryhill Business and tle Ferryhill Business and Enterprise College Science of our lives. Organised by DEBP 14/07/2016 (RAF) Enterprise College Durham NE1 - AFCO Newcas Dene Community tle School Presentations to Year 10 26/04/2016 (RAF) Dene Community School Peterlee NE1 - AFCO Newcas tle St Benet Biscop School ‘Futures Evening’ aimed at Year 11 and Sixth Form 04/07/2016 (RAF) St Benet Biscop School Bedlington LS1 - Area Hemsworth Arts and Office Community Academy Careers Fair 30/06/2016 Leeds Hemsworth Academy Pontefract LS1 - Area Office Gateways School Activity Day - PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds Gateways School Leeds LS1 - Area Grammar School at Office The Grammar School at Leeds PDT with CCF 09/05/2016 Leeds Leeds Leeds LS1 - Area Queen Ethelburgas Office College Careers Fair 18/04/2016 Leeds Queen Ethelburgas College York NE1 - AFCO Newcas City of Sunderland tle Sunderland College Bede College Careers Fair 20/04/2016 (RAF) Campus Sunderland LS1 - Area Office King James's School PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds King James's School Knareborough LS1 - Area Wickersley School And Office Sports College Careers Fair 27/04/2016 Leeds Wickersley School Rotherham LS1 - Area Office York High School Speed dating events for Year 10 organised by NYBEP 21/07/2016 Leeds York High School York LS1 - Area Caedmon College Office Whitby 4 x Presentation and possible PDT 22/04/2016 Leeds Caedmon College Whitby Whitby LS1 - Area Ermysted's Grammar Office School 2 x Operation -

Admissions Guide for Parents

Admissions to schools Guide for parents 2012 - 2013 If you live in Nottinghamshire, you can apply online at: www.nottinghamshire.gov.uk/schooladmissions NOTTINGHAMSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL ADMISSIONS TO SCHOOLS A GUIDE FOR PARENTS AND CARERS FOR THE SCHOOL YEAR 2012 - 2013 This booklet contains important information about how school places are allocated and the extra help available to you and your children. A summary of the leaflet and form is available in other languages. If you need help to understand what you need to do, contact your school’s head teacher or the School Admissions Team. URZ�D HRABSTWA NOTTINGHAMSHIRE PROCEDURY PRZYJ�� DO SZKÓ� PORADNIK DLA RODZICÓW I OPIEKUNÓW W ROKU SZKOLNYM 2012-2013 Broszura ta, zawiera istotne informacje, dotycz�ce procedur przyznawania miejsc w szko�ach oraz dodatkowej pomocy, jak� mog� uzyska� rodzice i ich dzieci. Konspekt i formularz dost�pne s� tak�e w innych j�zykach. Je�li potrzebujecie Pa�stwo pomocy w zrozumieniu co nale�y zrobi�, prosz� skontaktowa� si� z dyrektorem w�a�ciwej szko�y, b�d� dzia�em administracyjnym ds. przyj�� do szko�y. Broszura ta dost�pna jest równie� w j�zyku Braille’a, napisana du�� trzcionk�, a tak�e w formacie d�wi�kowym -na kasecie audio. Kontakt telefoniczny pod numerem: 01623 433499 This booklet is also available in braille, large print and audio tape. Please telephone 01623 433499. Contents Online admissions ..............................................................................................................2 Important dates - reception and infant to junior -

Nottinghamshire County Council’S Computerised Distance Measuring Software

Secondary Schools Nottinghamshire For Nottinghamshire community schools, the standard admission oversubscription criteria are detailed in the Admissions to schools: guide for parents. The application breakdown summary at the back of this document is based on information on national offer day 2 March 2015. For academy, foundation and voluntary aided schools which were oversubscribed in Year 7 for 2015/2016 it is not possible to list the criterion under which each application was granted or refused as the criteria for each of these schools is different and is applied by the individual admission authority. For details of allocation of places, please contact the school for further information. All school information is correct at the time of print (August 2015) but is subject to change. Linked Catholic Secondary schools outside of Nottinghamshire There are two Catholic secondary schools outside of Nottinghamshire which are linked to Nottinghamshire primary schools. For information on their oversubscription criteria, please contact the school or the relevant Local Authority for details Doncaster Local Authority St Joseph’s Catholic (Aided) Primary School, Retford and St Patrick’s Catholic (Aided) Primary, Harworth are linked to the McAuley Catholic High School, Specialist College for the Performing Arts, Cantley Lane, Doncaster, South Yorkshire - 01302 537396 www.mcauley.doncaster.sch.uk Derbyshire Local Authority Priory Catholic (Aided) Primary, Eastwood is linked to Saint John Houghton Catholic School, A Specialist Science College, Abbot -

Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle

Contextual Data Education Indicators: 2022 Cycle Schools are listed in alphabetical order. You can use CTRL + F/ Level 2: GCSE or equivalent level qualifications Command + F to search for Level 3: A Level or equivalent level qualifications your school or college. Notes: 1. The education indicators are based on a combination of three years' of school performance data, where available, and combined using z-score methodology. For further information on this please follow the link below. 2. 'Yes' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, meets the criteria for an education indicator. 3. 'No' in the Level 2 or Level 3 column means that a candidate from this school, studying at this level, does not meet the criteria for an education indicator. 4. 'N/A' indicates that there is no reliable data available for this school for this particular level of study. All independent schools are also flagged as N/A due to the lack of reliable data available. 5. Contextual data is only applicable for schools in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland meaning only schools from these countries will appear in this list. If your school does not appear please contact [email protected]. For full information on contextual data and how it is used please refer to our website www.manchester.ac.uk/contextualdata or contact [email protected]. Level 2 Education Level 3 Education School Name Address 1 Address 2 Post Code Indicator Indicator 16-19 Abingdon Wootton Road Abingdon-on-Thames -

Capital Programmes Appendices

2014/15 Integrated transport programme Scheduled Scheme construction start/ Sub-block/scheme Area Electoral Division budget reason for removal or (£000) delay Access to local facilities B6023 Mansfield Road, Sutton in Ashfield - upgrade of existing crossing facility Ashfield Sutton in Ashfield North £50k-£100k Quarter 2 Kirkby in Ashfield North / Kirkby in Chapel Street/The Hill, Kirkby in Ashfield - new pedestrian crossing Ashfield £50k-£100k Quarter 3 Ashfield South A60 Doncaster Road, Langold - upgrade of existing crossing facility Bassetlaw Blyth and Harworth £50k-£100k Quarter 3 Bridge Street, Worksop - amendment to parking arrangements (scheme carried over from 2013/14) Bassetlaw Worksop West £50k-£100k Quarter 3 and removal of signals at Ryton Street Thievesdale Lane, Worksop - new pedestrian crossing Bassetlaw Worksop North East and Carlton £50k-£100k Not programmed yet Swiney Way, Toton - refuge widening Broxtowe Chilwell and Toton ≤£25k Quarter 2 A60 Mansfield Road, Redhill - new pedestrian refuge Gedling Arnold North / Newstead ≤£25k Quarter 1 B684/Woodthorpe Drive, Woodthorpe - new pedestrian crossing Gedling Arnold South £50k-£100k Quarter 2 Moor Road/Park Road, Bestwood Village - junction improvements Gedling Newstead ≤£25k Quarter 3 Station Road (east of George Road), Carlton - new pedestrian crossing Gedling Carlton West £25k-£50k Quarter 2 A6097 Epperstone Bypass - new footway to connect Lowdham Lane, Woodborough with Lowdham Gedling / Newark & Calverton / Farnsfield & Lowdham £50k-£100k Quarter 3 Road, Epperstone over -

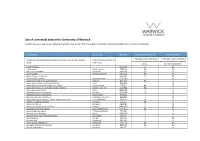

Use of Contextual Data at the University of Warwick

Use of contextual data at the University of Warwick The data below will give you an indication of whether your school meets the eligibility criteria for the contextual offer at the University of Warwick. School Name Town / City Postcode School Exam Performance Free School Meals 'Y' indicates a school with below 'Y' indcicates a school with above Schools are listed on alphabetical order. Click on the arrow to filter by school Click on the arrow to filter by the national average performance the average entitlement/ eligibility name. Town / City. at KS5. for Free School Meals. 16-19 Abingdon - OX14 1RF N NA 3 Dimensions South Somerset TA20 3AJ NA NA 6th Form at Swakeleys Hillingdon UB10 0EJ N Y AALPS College North Lincolnshire DN15 0BJ NA NA Abbey College, Cambridge - CB1 2JB N NA Abbey College, Ramsey Huntingdonshire PE26 1DG Y N Abbey Court Community Special School Medway ME2 3SP NA Y Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds LS16 5EA Y N Abbey Hill School and Performing Arts College Stoke-on-Trent ST2 8LG NA Y Abbey Hill School and Technology College, Stockton Stockton-on-Tees TS19 8BU NA Y Abbey School, Faversham Swale ME13 8RZ Y Y Abbeyfield School, Chippenham Wiltshire SN15 3XB N N Abbeyfield School, Northampton Northampton NN4 8BU Y Y Abbeywood Community School South Gloucestershire BS34 8SF Y N Abbot Beyne School and Arts College, Burton Upon Trent East Staffordshire DE15 0JL N Y Abbot's Lea School, Liverpool Liverpool L25 6EE NA Y Abbotsfield School Hillingdon UB10 0EX Y N Abbs Cross School and Arts College Havering RM12 4YQ N -

Anna Soubry MP Working Hard for Broxtowe

View in browser Unsubscribe Forward Please use the forward button above to send this on to a friend or neighbour - if they aren't on the internet please print if off for them! Best of all ask your friends and neighbours to sign up for my email newsletter through my website or by emailing me on [email protected] Anna Soubry MP working hard for Broxtowe www.annasoubry.org.uk E-newsletter| August 23 2013 "If only all ministers answered questions like Anna Soubry does." David Aaronovitch, The Times "she has a record of unusually free speech" Simon Carr, The Independent "part of the beating heart of the parliamentary Tory party" Quentin Letts, The Daily Mail Hello again, I am currently enjoying some sun, but wanted to send out a short newsletter to keep you updated on the latest Tram and Green Belt news, namely that the application for 555 houses at Nuthall has been rejected, as well as to congratulate all of our schools on their outstanding results. Although I am technically on holiday I continue to check my e-mails and my team on High Road are dealing with urgent queries on my behalf. as ever, Anna Exam success Congratulations to all of our schools on their excellent results. Bramcote College have beaten all their records in their A level results with 26.3% of students achieving A* or A grades compared to 14% last year. 40% were A*-B. GCSE pupils at The Bramcote School and Alderman White also achieved great results: 92% of the students gained A*-C in 5 or more subjects. -

Private Schools Dominate the Rankings Again Parents

TOP 1,000 SCHOOLS FINANCIAL TIMES SPECIAL REPORT | Saturday March 8 2008 www.ft.com/top1000schools2008 Winners on a learning curve ● Private schools dominate the rankings again ● Parents' guide to the best choice ● Where learning can be a lesson for life 2 FINANCIAL TIMES SATURDAY MARCH 8 2008 Top 1,000 Schools In This Issue Location, location, education... COSTLY DILEMMA Many families are torn between spending a small fortune to live near the best state schools or paying private school fees, writes Liz Lightfoot Pages 4-5 Diploma fans say breadth is best INTERNATIONAL BACCALAUREATE Supporters of the IB believe it is better than A-levels at dividing the very brainy from the amazingly brainy, writes Francis Beckett Page 6 Hit rate is no flash in the pan GETTING IN Just 30 schools supply a quarter of successful Oxbridge applicants. Lisa Freedman looks at the variety of factors that help them achieve this Pages 8-9 Testing times: pupils at Colyton Grammar School in Devon, up from 92nd in 2006 to 85th last year, sitting exams Alamy It's not all about learning CRITERIA FOR SUCCESS In the pursuit of better academic performance, have schools lost sight of the need to produce happy pupils, asks Miranda Green Page 9 Class action The FT Top 1,000 MAIN LISTING Arranged by county, with a guide by Simon Briscoe Pages 10-15 that gets results ON THE WEB An interactive version of the top notably of all Westminster, and then regarded as highly them shows the pressure 100 schools in the ranking, and more tables, The rankings are which takes bright girls in academic said the school heads feel under. -

Broxtowe Primary Schools Broxtowe

Broxtowe Broxtowe Primary Schools Broxtowe - 2016 information school For Nottinghamshire community and voluntary controlled schools, the standard oversubscription criteria are detailed in the Admissions to schools: guide for parents. The application breakdown at the back of this document is based on information on national offer day 16 April 2015. For academy, foundation and voluntary aided schools which were oversubscribed in the intake year for 2015/2016 it is not possible to list the criterion under which each application was granted or refused as the criteria for each of these schools is different and is applied by the individual admission authority. For details of allocation of places, please contact the school for further information. - All school information is correct at the time of print (August 2015) but is subject to change. 2017 1. Albany Infant and Nursery School (5-7 community school) Mrs Helen Webster 0115 917 9212 Grenville Drive, Stapleford, Nottingham, [email protected] NG9 8PD www.albanyinfants.co.uk DfE number 891 2301 Published admission number 60 Expected number on roll 167 Linked junior school: Albany Junior School See standard reception criteria on page 17 2. Albany Junior School (7-11 community school) Mr Craig Robertson 0115 917 6550 Pasture Road, Stapleford, Nottingham, [email protected] NG9 8HR www.albanyjunior.co.uk DfE number 891 2300 Published admission number 60 Expected number on roll 184 Linked infant school: Albany Infant and Nursery School Linked secondary schools: Alderman White School and The Bramcote School (part of White Hills Park Federation) See standard junior/primary criteria on page 17 1 Broxtowe Broxtowe Primary Schools Broxtowe - 2016 information school 3.