All-Dielectric Thermonanophotonics Arxiv:2104.01964V1 [Physics.Optics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yuri Kivshar

Chief Investigator: Yuri Kivshar Researchers and students Dr. Dragomir Neshev, Dr. Andrey Sukhorukov, Dr. Andrey Miroshnichenko, Dr. Zhiyong Xu, Dr. Ivan Garanovich, Dr. Ilya Shadrivov, Mr. Francis Bennet, Mr. Arthur Davoyan, Mr. Sangwoo Ha, Mr. Alexander Minovich, Mr Alexander Solntsev Awards, honours, major international visits His recent awards include the The Peter Baum Award of the Australian National University, Carl Zeiss Visiting Professor Award from the University of Jena and the Carl Zeiss Foundation, and Distinguished Award from the Wenner-Gren Foundation in Sweden. In 2010 he was awarded by the title Distinguished Professor of the Australian National University. In 2010 he visited more than 15 research laboratories (where presented colloquia or invited seminars) including University of Cape Town (South Africa), University of Santiago de Chile (Chile), University of Concepcion (Chile), Sun Sen-Yat University (China), Los Alamos National Laboratory (USA), University of Odessa (Ukraine), Sandia Laboratories (USA), Texas A&M University of Qatar (Doha, Qatar), Institute for Low Temperature Physics (Kharkov, Ukraine), Institute for Radio-Electronics (Kharkov, Ukraine), St Petersburg State University (Russia). He was invited to organize a mini-symposium at the PIERS Meeting in Xian (March 2010), and also a symposium on Nonlinear optics and nanophotonics in the framework of the second international conference: “Nonlinear waves – Theory and Applications” (Beijing, June 26-29, 2010) In 2010, Yuri Kivshar presented 12 invited and keynote talks Yuri Kivshar received his PhD in 1984 from the USSR Academy including Photonic localization and band gaps (ICPBG) (Guangzhou, of Science and was at the Institute for Low Temperature Physics China), International Workshop on Complexity in Periodically and Engineering (Kharkov, Ukraine). -

Yuri Kivshar

The Centre for Ultrahigh bandwidth Devices for Optical Systems (CUDOS) The Centre for Ultrahigh bandwidth Devices for Optical Systems (CUDOS) An Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence Sydney Laboratory and Headquarters Professor Ben Eggleton, Research Director Phone: (02) 9351 3604 (+612 9351 3604) Dr Chris Walsh, Chief Operations Officer Phone (02) 9351 5897 (+612 9351 5897) School of Physics, A28 University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia Fax: (02) 9531 7726 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cudos.org.au CUDOS@ANU CUDOS@Swinburne Ms Wendy Quinn Professor Min Gu Director’s Unit Centre for Micro-Photonics Research School of Physical Sciences and Engineering Swinburne University of Technology The Australian National University PO Box 218, Hawthorn ACT 0200 Australia VIC 3122 Australia Phone: (02) 6125 3423 Phone: (03) 9214 8776 CUDOS@Macquarie CUDOS@UTS Dr Michael Withford Professor Lindsay Botten Department of Physics Department of Mathematical Sciences Division of Information and Communication Sciences University of Technology Sydney Macquarie University PO Box 123 NSW 2109 Australia Broadway NSW 2007 Australia ANNUAL REPORT Phone: (02) 9850 7056 Phone: (02) 9514 2247 Ms Kali Madden Phone: 9850 8931 2006 DEPUTY DIRECTOR Professor Yuri Kivshar photonic crystals, to enhance its development in Australia and provide linkages between leading edge R&D and industry in an important emerging technology. His current research activities, which fit within two CUDOS Flagship projects Slow Light and Tunable Microphotonics, involve the studies of spatiotemporal dynamics of light propagation, nonlinear interaction and control of light in periodic photonic structures, and theoretical studies of photonic crystals and related devices. Research achievements during 2006 Yuri Kivshar received his PhD in 1984 from the USSR Academy of Slow-light optical bullets in nonlinear Bragg-grating Science and was at the Institute for Low Temperature Physics and waveguide arrays Engineering (Kharkov, Ukraine). -

META'17 Incheon

META’17 Incheon - Korea The 8th International Conference on Metamaterials, Photonic Crystals and Plasmonics Program July 25 – 28, 2017 Incheon, Korea metaconferences.org .metaconferences.org META’17 Incheon - Korea The 8th International Conference on Metamaterials, Photonic Crystals and Plasmonics Please share your comments, photos & videos ! www.facebook.com/metaconference @metaconference Edited by Said Zouhdi | Paris-Sud University, France Junsuk Rho | POSTECH, Korea Hakjoo Lee | CAMM, Korea CONTENTS META’17 ORGANIZATION ........................................ 5 PLENARY SPEAKERS ........................................... 7 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS ........................................... 12 META’17 VENUE ............................................... 14 GUIDELINES FOR PRESENTERS ................................... 17 PRE-CONFERENCE TUTORIALS ................................... 18 TECHNICAL PROGRAM .......................................... 30 META’17 ORGANIZATION Said Zouhdi, General Chair Junsuk Rho, General Co-Chair Hakjoo Lee, General Co-Chair Paris–Sud University, France POSTECH, Korea CAMM, Korea INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE Harry Atwater, USA Graeme W. Milton, USA Ari Sihvola, Finland Federico Capasso, USA Raj Mittra, USA David R. Smith, USA Andre de Lustrac, France Manuel Nieto-Vesperinas, Spain J(Yiannis) Vardaxoglou, UK Nader Engheta, USA Susumu Noda, Japan Martin Wegener, Germany Teruya Ishihara, Japan Masaya Notomi, Japan Xiang Zhang, USA Tatsuo Itoh, USA Yahya Rahmat-Samii, USA Nikolay Zheludev, UK Yuri Kivshar, Australia -

Manipulating Electromagnetic Fields with Advanced Metamaterials

Manipulating Electromagnetic Fields with Advanced Metamaterials A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University Alexey P. Slobozhanyuk June 2017 ______________________________________________________________________________ Declaration ______________________________________________________________________________ This thesis is an account of research undertaken in the Nonlinear Physics Centre within the Research School of Physics and Engineering at the Australian National University between July 2014 and June 2017 while I was enrolled for the Doctor of Philosophy degree. The research has been conducted under the supervision of a supervisory panel comprising Dr. David A. Powell, A/Prof. Andrey E. Miroshnichenko, A/Prof. Ilya V. Shadrivov and Prof. Yuri S. Kivshar, and also within the collaboration agreement between the Australian National University in Canberra (Australia) and the ITMO University in St. Petersburg (Russia), being also supervised by Prof. Pavel A. Belov from the ITMO University, Russia. Unless specifically stated otherwise, the material presented within this thesis is my own original research work. None of the work presented here has ever been submitted for any degree at this or any other institution of learning. Alexey P. Slobozhanyuk June 2017 iii iv To my beloved: parents, wife, and grandma Моим любимым: родителям, жене и бабушке v vi ______________________________________________________________________________ List of Publications ______________________________________________________________________________ Papers with the results included in this thesis: 1. Alexey P. Slobozhanyuk, Alexander N. Poddubny, Andrey E. Miroshnichenko, Pavel A. Belov, and Yuri S. Kivshar, "Subwavelength topological edge states in optically resonant dielectric structures", Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 123901 (2015). 2. Alexey P. Slobozhanyuk, Alexander N. Poddubny, Andrey E. Miroshnichenko, Ivan S. Sinev, Ivan S. Mukhin, Anton K. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Schedule at a Glance ....................................... 2 Special Symposia Townes Symposium: Reminiscences – Scientific and Personal . 15 FiO/LS Chairs’ Welcome Letters .............................. 3 International Year of Light – Science to Solutions . 15 General Information ........................................ 5 Symposium on Photoreceptor Analysis and Single-cone-mediated Vision ............................................... 16 Conference Services . 5 Laser Science Symposium on Undergraduate Research . 16 First Aid and Emergency Information . 6 Symposium on Optics for Global Health and Low Resource Sponsoring Society Booths . 6 Settings . 17 Stay Connected Symposium Honoring Adolf Lohmann...................... 17 Conference Materials.................................... 7 Symposium on Optical Remote Sensing for the Climate . 17 FiO/LS Mobile App . 8 Symposium on Applications of Low Noise Frequency Combs . 18 Conference Plenary Session and Awards Ceremony Special Events . 19 Plenary Presentations.................................... 9 APS Arthur L. Schawlow Prize and Lecture . 10 Exhibition Information ..................................... 23 Frederic Ives Medal /Jarus W. Quinn Prize Presentation FiO/LS Committees . 24 and Lecture . 10 OSA Awards and Honors ................................. 11 Explanation of Session Codes ............................... 25 Awards and Special Recognitions FiO/LS Agenda of Sessions ................................. 26 OSA Foundation Boris P. Stoicheff Memorial Scholarship....... -

Active and Tunable Metamaterials Allan D

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Birck and NCN Publications Birck Nanotechnology Center 3-2011 Active and tunable metamaterials Allan D. Boardman University of Salford, [email protected] Volodymyr V. Grimalsky Autonomous University of the State of Morelos Yuri S. Kivshar Australian National University Mikhail Lapine University of Sevilla Natalia Litchinitser State University of New York See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/nanopub Part of the Nanoscience and Nanotechnology Commons Boardman, Allan D.; Grimalsky, Volodymyr V.; Kivshar, Yuri S.; Lapine, Mikhail; Litchinitser, Natalia; Koshevaya, Svetlana; Noginov, Mikhail; Malnev, Vadim N.; Rapoport, Yuriy; and Shalaev, Vladimir M., "Active and tunable metamaterials" (2011). Birck and NCN Publications. Paper 1048. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/lpor.201000012 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Authors Allan D. Boardman, Volodymyr V. Grimalsky, Yuri S. Kivshar, Mikhail Lapine, Natalia Litchinitser, Svetlana Koshevaya, Mikhail Noginov, Vadim N. Malnev, Yuriy Rapoport, and Vladimir M. Shalaev This article is available at Purdue e-Pubs: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/nanopub/1048 LASER & PHOTONICS Laser Photonics Rev. 5, No. 2, 287–307 (2011) / DOI 10.1002/lpor.201000012 REVIEWS Abstract Metamaterial research is an extremely important global activity that promises to change our lives in many dif- ferent ways. These include making objects invisible and the dramatic impact of metamaterials upon the energy and medical sectors of society. Behind all of the applications, however, lies the business of creating metamaterials that are not going to be crippled by the kind of loss that is naturally heralded by use of resonant responses in their construction. -

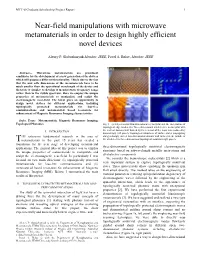

Near-Field Manipulations with Microwave Metamaterials in Order to Design Highly Efficient Novel Devices

MTT-S Graduate Scholarship Project Report 1 Near-field manipulations with microwave metamaterials in order to design highly efficient novel devices Alexey P. Slobozhanyuk Member, IEEE, Pavel A. Belov, Member, IEEE Abstract— Microwave metamaterials are prominent candidates for the development of a new generation of the devices which will possess a different functionality. This is due to the fact that the unit cells dimensions of the metamaterials have to be much smaller than the operational wavelength of the device and therefore it simpler to develop it in microwave frequency range rather than in the visible spectrum. Here we employ the unique properties of metamaterials to manipulate and sculpt the electromagnetic near-field. The latest gives an opportunity to design novel devices for different applications, including topologically protected metamaterials for loss-free communications and metamaterial based resonators for enhancement of Magnetic Resonance Imaging characteristics Index Terms—Metamaterials, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Topological Photonics Fig. 1. (a) Experimental two-dimensional metacrystal and the observation of topological edge modes. (b) Three-dimensional all-dielectric metacrystal with the vertical domain wall formed by the reversal of the mass term induced by I. INTRODUCTION bianisotropy (left panel). Topological robustness of surface states propagating HE extensive fundamental research in the area of along a sharply curved two-dimensional domain wall formed in the middle of metamaterials in the past 15 years has created a the all-dielectric three-dimensional topological insulator (right panel). T foundation for the next stage of developing metamaterial three-dimensional topologically nontrivial electromagnetic applications. The general idea of this project was to employ structures based on subwavelength metallic meta-atoms and the unique properties of metamaterials to manipulate and all-dielectric components. -

Topological Photonics on a Small Scale

Topological Photonics on a Small Scale Dmitry V. Zhirihin1 and Yuri S. Kivshar1,2 1School of Physics and Engineering, ITMO University, St. Petersburg 197101, Russia 2Nonlinear Physics Center, Research School of Physics, Australian National University Canberra ACT 2601, Australia Keywords: topological photonics, SSH model, zigzag arrays, higher-order topological states, polaritons Abstract The study of topological phases of light suggests novel opportunities for creating robust optical structures and on-chip photonic devices which are immune against scattering losses and structural disorder. However, many recent demonstrations of topological effects in optics employ structures with relatively large scales. Here we discuss the physics and realisation of topological photonics on small scales, with the dimensions often smaller or comparable with the wavelength of light. We highlight the recent experimental demonstrations of small-scale topological states based on arrays of resonant nanoparticles and discuss a novel photonic platform employing higher-order topological effects for creating subwavelength highly efficient topologically protected optical cavities. We pay a special attention to the recent progress on topological polaritonic structures and summarize with our vision on the future directions of nanoscale topological photonics and its impact on other fields. 1 1. Introduction Nanophotonics studies the behavior of light on nanometer scales as well as the interaction of nanometer-sized objects with light. Traditionally, the field of -

Energy Localization, Fano Resonances, and Nonlinear Meta-Optics

Low Temperature Physics/Fizika Nizkikh Temperatur, 2018, v. 44, No. 7, pp. 924–932 Energy localization, Fano resonances, and nonlinear meta-optics Yuri Kivshar Nonlinear Physics Center, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia ITMO University, St. Petersburg 197101, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Received January 22, 2018, published online May 28, 2018 This paper reflects on some memories of the research topics developed at Department No. 29 of the Institute for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering in Kharkov more than 30 years ago. It also provides some recent advances on my major research activities related to those topics, including energy localization and solitons in nonlinear lattices, Fano resonances in photonics and phononics, and nonlinear effects in meta-optics and nanophotonics. Curiously enough, each of those topics can be associated with some memories and discussions that happened in Kharkov long time ago. PACS: 45.05.+x General theory of classical mechanics of discrete systems; 63.20.Pw Localized modes; 42.25.Hz Interference; 42.65.Ky Frequency conversion; harmonic generation, including higher-order harmonic generation. Keywords: localized modes, metamaterials, Fano resonances, nanophotonics, nonlinear meta-optics. 1. Introduction Another broad area of research was associated with the study of localized solutions (domain walls, solitons, vorti- Research topics at Department No. 29 of the Institute ces) of the semiclassical Landau–Lifshitz equations de- for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering in Kharkov scribing the nonlinear spin dynamics in magnetism. This were quite diverse, but they were mainly based on ideas background environment and discussions were probably from solid states physics and theory of magnetism, in spite responsible for my later interest in metamaterials. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Yuri Kivshar, FAA, FAIP, FOSA, FAPS

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Yuri Kivshar, FAA, FAIP, FOSA, FAPS, FInstP Head, Nonlinear Physics Center, Research School of Physics and Engineering Australian National University Personal Data Name & Surname: Yuri Kivshar Date of Birth & Nationality: 3 April 1959, Dual Nationality: Australia, Ukraine Address: 39 Twelvetrees Crescent, Florey ACT 2615, Australia Business Address: Nonlinear Physics Center, Research School of Physics and Engineering, Australian National University, Canberra ACT 0200 Australia e-mail/web: [email protected], http://wwwrsphysse.anu.edu.au/nonlinear/ Education 1976-1981: Study of physics at the National Kharkov University, Ukraine 1981: Graduated summa cum laude with Master of Science in Physics, National Kharkov University, Ukraine 1981-1984: Graduate studies at the Institute for Low Temperature Physics and Engineering, Ukraine 1984: Awarded a PhD degree in Physics and Mathematics, Kharkov, Ukraine Professional Career 1981: Graduated summa cum laude with Master of Science in Physics, National Kharkov University, Ukraine 1984: Awarded a PhD degree in Physics and Mathematics, Kharkov, Ukraine 1986: Appointed Research Fellow, Institute for Low Temperature Physics, Kharkov, Ukraine 1989: Promoted to Senior Research Fellow, Institute for Low Temperature Physics, Kharkov, Ukraine 1990: Appointed Visiting Professor, Physics Department of the Complutense University, Madrid, Spain 1991: Awarded Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellowship, University of Düsseldorf, Germany 1993: Appointed Fellow, Australian National University,