The Archaeology of Maize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Central American Maize Genomes Suggest Ancient Gene Flow from South America

Archaeological Central American maize genomes suggest ancient gene flow from South America Logan Kistlera,1, Heather B. Thakarb, Amber M. VanDerwarkerc, Alejandra Domicd,e, Anders Bergströmf, Richard J. Georgec, Thomas K. Harperd, Robin G. Allabyg, Kenneth Hirthd, and Douglas J. Kennettc,1 aDepartment of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560; bDepartment of Anthropology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843; cDepartment of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, CA 93106; dDepartment of Anthropology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; eDepartment of Geosciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802; fAncient Genomics Laboratory, The Francis Crick Institute, NW1 1AT London, United Kingdom; and gSchool of Life Sciences, University of Warwick, CV4 7AL Coventry, United Kingdom Edited by David L. Lentz, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Elsa M. Redmond November 3, 2020 (received for review July 24, 2020) Maize (Zea mays ssp. mays) domestication began in southwestern 16). However, precolonial backflow of divergent maize varieties Mexico ∼9,000 calendar years before present (cal. BP) and humans into Central and Mesoamerica during the last 9,000 y remains dispersed this important grain to South America by at least 7,000 understudied, and could have ramifications for the history of cal. BP as a partial domesticate. South America served as a second- maize as a staple in the region. ary improvement center where the domestication syndrome be- Morphological evidence from ancient maize found in ar- came fixed and new lineages emerged in parallel with similar chaeological sites combined with DNA data confirms a complex processes in Mesoamerica. -

Popped Secret: the Mysterious Origin of Corn Film Guide Educator Materials

Popped Secret: The Mysterious Origin of Corn Film Guide Educator Materials OVERVIEW In the HHMI film Popped Secret: The Mysterious Origin of Corn, evolutionary biologist Dr. Neil Losin embarks on a quest to discover the origin of maize (or corn). While the wild varieties of common crops, such as apples and wheat, looked much like the cultivated species, there are no wild plants that closely resemble maize. As the film unfolds, we learn how geneticists and archaeologists have come together to unravel the mysteries of how and where maize was domesticated nearly 9,000 years ago. KEY CONCEPTS A. Humans have transformed wild plants into useful crops by artificially selecting and propagating individuals with the most desirable traits or characteristics—such as size, color, or sweetness—over generations. B. Evidence of early maize domestication comes from many disciplines including evolutionary biology, genetics, and archaeology. C. The analysis of shared characteristics among different species, including extinct ones, enables scientists to determine evolutionary relationships. D. In general, the more closely related two groups of organisms are, the more similar their DNA sequences will be. Scientists can estimate how long ago two populations of organisms diverged by comparing their genomes. E. When the number of genes is relatively small, mathematical models based on Mendelian genetics can help scientists estimate how many genes are involved in the differences in traits between species. F. Regulatory genes code for proteins, such as transcription factors, that in turn control the expression of several—even hundreds—of other genes. As a result, changes in just a few regulatory genes can have a dramatic effect on traits. -

Botany and Conservation Biology Alumni Newsletter 3 NEWS & NOTES NEWS & NOTES

Botany & Conservation A newsletter for alumni and friends of Botany and Conservation Biology Fall/Winter 2017 Unraveling the secret to the unique pigment of beets - page 5 The many colors of the common beet Mo Fayyaz retires Letters to a A virtual museum Contents 3 4 pre-scientist 6 reunion botany.wisc.edu conservationbiology.ls.wisc.edu NEWS & NOTES NEWS & NOTES Chair’s Letter Longtime botany greenhouse director Mo Fayyaz retires Adapted from a story by Eric Hamilton sense of inevitable change in the air. At Those seminal collections, intended hen the Iranian government plants. Fayyaz and his greenhouse staff overseeing the work himself. The garden the same time, autumn in Wisconsin to encourage interest in the natural Woffered Mo Fayyaz a full schol- have grown a dizzying array of plants organizes plants by their family rela- always evokes a feeling of comfort in the resources of Wisconsin, grew quickly arship to study horticulture abroad, a used by 14 lecture and laboratory courses tionships and features several unique familiar – botany students are once again and would ultimately serve as the cradle simple oversight meant the University as well as botanical research labs. The specimens, such as a direct descendent out trying to ID asters and goldenrods. of origin for most of the natural science of Wisconsin–Madison was not his top greenhouse climates range from humid, of Isaac Newton’s apple tree, said to have It’s that enigmatic sense of the familiar disciplines that have propelled UW- choice. tropical jungles nurturing orchids to arid inspired the physicist’s theory of gravity. -

Who Doesn't Love Fresh Corn on the Cob in the Summer?

Corn Ahh - who doesn’t love fresh corn on the cob in the summer? It is so good, and so good for you! It not only provides the necessary calories for daily metabolism, but is a rich source of vitamins A, B, E and many minerals. Its high fiber content ensures that it plays a role in prevention of digestive ailments. Growing info: We're expanding our sweet corn production this year by popular demand. The issue with corn, is it takes a lot of space. You can get about 100 ears from every 100 row-feet of planting. When a share consists of 8 ears of corn, this is 8 feet for one share! We plant corn in succession starting in mid May. This will give us a constant supply through summer. Common Problems: Corn ear worms are the TIPS: major pest we deal with in corn. They are tiny little worms that crawl into the tip of the ear and Short-term Storage: Corn converts it's start eating. By the time they get an inch down sugars into starch soon after peak the tip of the ear, they will have grown to a large ripeness, so best to eat it soon. and ugly size. We prevent ear worm by injecting Otherwise, store in a very cold a small amount of vegetable oil into the tips refrigerator. before the worms have a chance of crawling in. Long-term Storage: Cut kernels off the cobs and freeze. You’ll probaby see mostly white corn in 2011. Recipes--Corn Summer Corn Salad 2 pinches kosher salt Core the tomatoes and cut a 8 ears fresh corn 6 ears corn, husked and cleaned small X on the bottom of each. -

Conserving Agrobiodiversity Amid Global Change, Migration, and Nontraditional Livelihood Networks: the Dynamic Uses of Cultural Landscape Knowledge

Copyright © 2014 by the author(s). Published here under license by the Resilience Alliance. Zimmerer, K. S. 2014. Conserving agrobiodiversity amid global change, migration, and nontraditional livelihood networks: the dynamic uses of cultural landscape knowledge. Ecology and Society 19(2): 1. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-06316-190201 Research, part of a Special Feature on Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Cultural Landscapes: Analysis and Management Options Conserving agrobiodiversity amid global change, migration, and nontraditional livelihood networks: the dynamic uses of cultural landscape knowledge Karl S. Zimmerer 1 ABSTRACT. I examined agrobiodiversity in smallholder cultural landscapes with the goal of offering new insights into management and policy options for the resilience-based in situ conservation and social-ecological sustainability of local, food-producing crop types, i.e., landraces. I built a general, integrative approach to focus on both land use and livelihood functions of crop landraces in the context of nontraditional, migration-related livelihoods amid global change. The research involved a multimethod, case-study design focused on a cultural landscape of maize, i.e., corn, growing in the Andes of central Bolivia, which is a global hot spot for this crop’s agrobiodiversity. Central questions included the following: (1) What are major agroecological functions and food-related services of the agrobiodiversity of Andean maize landraces, and how are they related to cultural landscapes and associated knowledge systems? (2) What are new migration-related livelihood groups, and how are their dynamic livelihoods propelled through global change, in particular international and national migration, linked to the use and cultural landscapes of agrobiodiversity? (3) What are management and policy options derived from the previous questions? Combined social-ecological services as both cultivation and food resources are found to function in relation to the cultural landscape. -

A STUDY on the USE of METAL SILOS for SAFER and BETTER TS ORAGE of GUATEMALAN MAIZE José Rodrigo Mendoza University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Food Science and Technology Department Science and Technology 7-2016 FROM MILPAS TO THE MARKET: A STUDY ON THE USE OF METAL SILOS FOR SAFER AND BETTER TS ORAGE OF GUATEMALAN MAIZE José Rodrigo Mendoza University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/foodscidiss Part of the Agricultural Economics Commons, Agricultural Science Commons, Environmental Microbiology and Microbial Ecology Commons, Food Microbiology Commons, Food Security Commons, Other Food Science Commons, and the Toxicology Commons Mendoza, José Rodrigo, "FROM MILPAS TO THE MARKET: A STUDY ON THE USE OF METAL SILOS FOR SAFER AND BETTER TS ORAGE OF GUATEMALAN MAIZE" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology. 75. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/foodscidiss/75 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Food Science and Technology Department at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research in Food Science and Technology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. i FROM MILPAS TO THE MARKET: A STUDY ON THE USE OF METAL SILOS FOR SAFER AND BETTER STORAGE OF GUATEMALAN MAIZE by José Rodrigo Mendoza A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Science Major: Food Science & Technology Under the supervision of Professor Jayne Stratton Lincoln, Nebraska July, 2016 ii FROM MILPAS TO THE MARKET: A STUDY ON THE USE OF METAL SILOS FOR SAFER AND BETTER STORAGE OF GUATEMALAN MAIZE José Rodrigo Mendoza, M.S. -

Brochure Iltis.Pdf

Hugh H. Iltis Doctor Honoris Causa 2 El maíz ha sido una de las grandes contribuciones de México al mundo y el Dr. Hugh Iltis es uno de los científicos que con mayor tenacidad ha dedicado su vida a desentrañar los misterios evolutivos del segundo grano de mayor importancia en el planeta. La Universidad de Guadalajara brinda un reconocimiento al trabajo del Dr. Iltis, colaborador nuestro durante tres décadas ininterrumpidas, cuyas aportaciones no sólo representan avances ante los desafíos intelectuales de la investigación básica, sino también en la formación de recursos humanos, y en la aplicación práctica del conocimiento para la conservación de los recursos naturales y alimentarios de un mundo en franco deterioro. Historia personal Hugh H. Iltis nació el 7 de abril de 1925 en Brno, Checoslovaquia. Su padre, el destacado naturista Hugo Iltis, fue profesor de Biología, Botánica y Genética en Brünn Checoslovaquia y profesor de Biología en la Universidad de Virginia. Siendo niño tuvo que migrar a los Estados Unidos de Norteamérica como refugiado cuando su país fue invadido por los nazis. Estimulado por su padre, se interesó en la genética y la botánica, muy pronto se entusiasmó por la Taxonomía y la Evolución de las plantas. Su carrera como botánico inició a muy temprana edad, pues a los 14 años ya había construido su propio herbario, y los ejemplares contaban con sus nombres en latín y descripciones. Estos ejemplares tuvieron que ser vendidos para ayudarse en sus estudios en la Universidad de Tennessee. Al año de haber iniciado en la universidad, tuvo que incorporarse al ejército de los Estados Unidos durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial, donde participó como analista de información 3 Hugh H. -

Visualization and Collaborative Practice in Paleoethnobotany

ARTICLE VISUALIZATION AND COLLABORATIVE PRACTICE IN PALEOETHNOBOTANY Jessica M. Herlich and Shanti Morell-Hart Jessica M. Herlich is a Ph.D. candidate at the College of William and Mary and Shanti Morell-Hart is Assistant Professor at McMaster University. aleoethnobotany lends unique insight into past lived Methodologies, Practices, and Multi-Proxy Understandings experiences, landscape reconstruction, and ethnoecolog- There are many methodologies within paleoethnobotany that ical connections. A wide array of paleoethnobotanical P lead to distinct yet complementary pieces of information, methodologies equips us to negotiate complementary under- whether due to scale of residue (chemical to architectural) or the standings of the human past. From entire wood sea vessels to technology available (hand loupes to full laboratory facilities). individual plant cells, all sizes of botanical remains can be The limits of archaeobotanical analysis are constantly expand- addressed through the tools available to an archaeobotanist. As ing as the accessibility and capabilities of technology improve. paleoethnobotanical interpretation is interwoven with other This is true for microscopes and software, which make it possi- threads of information, an enriched vision of the relationships ble for a paleoethnobotanist to capture and enhance the small- between landscape and people develops. est of cellular structures, and for telecommunications and digi- tal records, which are expanding the possibilities for decipher- Collaboration is a necessary component for archaeobotanical ing archaeobotanical material and for collaborating with distant analysis and interpretation. Through collaboration we make stakeholders. Improvements in technology are an integral part the invisible visible, the unintelligible intelligible, the unknow- of the exciting future of paleoethnobotany, which includes col- able knowable. -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

Land Report the Land Institute ∙ Spring 2011 the Land Institute

LAND REPORT THE LAND INSTITUTE ∙ SPRING 2011 THE LAND INSTITUTE MISSION STATEMENT DIRECTORS When people, land and community are as one, all three members Anne Simpson Byrne prosper; when they relate not as members but as competing inter- Vivian Donnelley Terry Evans ests, all three are exploited. By consulting nature as the source and Pete Ferrell measure of that membership, The Land Institute seeks to develop an Jan Flora agriculture that will save soil from being lost or poisoned, while pro- Wes Jackson moting a community life at once prosperous and enduring. Patrick McLarney Conn Nugent Victoria Ranney OUR WORK Lloyd Schermer Thousands of new perennial grain plants live year-round at The Land John Simpson Institute, prototypes we developed in pursuit of a new agriculture Donald Worster that mimics natural ecosystems. Grown in polycultures, perennial Angus Wright crops require less fertilizer, herbicide and pesticide. Their root sys- tems are massive. They manage water better, exchange nutrients more STAFF e∞ciently and hold soil against the erosion of water and wind. This Scott Bontz strengthens the plants’ resilience to weather extremes, and restores Carrie Carpenter Marty Christians the soil’s capacity to hold carbon. Our aim is to make conservation a Cindy Cox consequence, not a casualty, of agricultural production. Sheila Cox Stan Cox LAND REPORT Lee DeHaan Ti≠any Durr Land Report is published three times a year. issn 1093-1171. The edi- Jerry Glover tor is Scott Bontz. To use material from the magazine, reach him at Adam Gorrell [email protected], or the address or phone number below. -

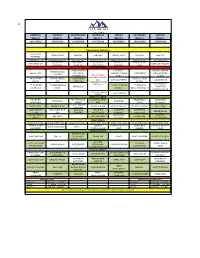

Cy an Entrée Consists of One Item As Listed in the Entrée Section

Cy MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY Week 1 Week 1 Week 1 Week 1 Week 1 Week 1 Week 1 10/14/2019 10/15/2019 10/16/2019 10/17/2019 10/18/2019 10/19/2019 10/20/2019 BREAKFAST ENTREES BLUEBERRY FRENCH TOAST WAFFLES PANCAKES FRENCH TOAST PANCAKES WAFFLES PANCAKES SAUSAGE PATTIES CORNED BEEF HASH COUNTRY HAM SAUSAGE PATTIES SMOKED SAUSAGE SAUSAGE LINKS SPICY CHICKEN BREAKFAST BREAKFAST BREAKFAST BREASFAST HAM & CHEESE EGGS BENEDICT VEGETABLE QUICHE CASSEROLE BURRITOS ENCHILADAS CASSEROLE EGGS LUNCH ENTRÉE FRIED CHICKEN HICKORY HERBED LEMON HONEY GARLIC BEEF STEW W/ MAPLE SMOKED PULLED STROMBOLI GRILLED PORK CHICKEN CORNBREAD TACO THURSDAY PORK CHOPS FRIED PORK HOISIN GLAZED HERB BAKED SEASONED GROUND FRIED CHICKEN BEEF BAYOU CATFISH CUBED STEAK CHOPS RIBS CHICKEN SHREDDED CHICKEN WINGS ** SUNDRIED ** STUFFED **VEGETABLE LO FISH TACOS ** VEG. STUFFED ** TOMATO MEATLOAF TOMATO & TOMATOES MEIN SQUASH BASIL MANICOTTI SPINACH PASTA ** STUFFED POBLANO HUSHPUPPIES PEPPERS SIDES AT LUNCH AUGRATIN WHITE RICE & CILANTRO LIME MOZERALLA SCALLOPED FRIED RICE RED RICE POTATOES GRAVY RICE STICKS POTATOES LOADED MASHED WHITE RICE JASMINE RICE REFRIED BEANS MAC & CHEESE POTATO WEDGES RICE PILAF POTATOES CORN ON THE MANDARIN STIR- SOUTHERN MEXICAN SAUTEED PARMESAN GREEN BEANS COB FRY COLLARDS VEGETABLES CABBAGE BROCCOLI SAUTEED GREEN GREEN BEAN ROASTED BOY CHOY SAUTEED CORN SUCCOTASH BEANS CASSEROLE CAULIFLOWER DAILY SOUPS Soup of the Day Soup of the Day Soup of the Day Soup of the Day Soup of the Day Soup of the Day Soup of the Day CRAB -

Archaeologically Defining the Earlier Garden Landscapes at Morven: Preliminary Results

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons University of Pennsylvania Museum of University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Papers Archaeology and Anthropology 1987 Archaeologically Defining the Earlier Garden Landscapes at Morven: Preliminary Results Anne E. Yentsch Naomi F. Miller University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Barbara Paca Dolores Piperno Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Yentsch, A. E., Miller, N. F., Paca, B., & Piperno, D. (1987). Archaeologically Defining the Earlier Garden Landscapes at Morven: Preliminary Results. Northeast Historical Archaeology, 16 (1), 1-29. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/26 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/penn_museum_papers/26 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Archaeologically Defining the Earlier Garden Landscapes at Morven: Preliminary Results Abstract The first phase of archaeology at Morven was designed to test the potential for further study of the early garden landscape at a ca. 1758 house in Princeton, New jersey. The research included intensive botanical analysis using a variety of archaeobotanical techniques integrated within a broader ethnobotanical framework. A study was also made of the garden's topography using map analysis combined with subsurface testing. Information on garden features related to the design of earlier garden surfaces