Phasmid Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecomorph Convergence in Stick Insects (Phasmatodea) with Emphasis on the Lonchodinae of Papua New Guinea

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2018-07-01 Ecomorph Convergence in Stick Insects (Phasmatodea) with Emphasis on the Lonchodinae of Papua New Guinea Yelena Marlese Pacheco Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Life Sciences Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Pacheco, Yelena Marlese, "Ecomorph Convergence in Stick Insects (Phasmatodea) with Emphasis on the Lonchodinae of Papua New Guinea" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 7444. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7444 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Ecomorph Convergence in Stick Insects (Phasmatodea) with Emphasis on the Lonchodinae of Papua New Guinea Yelena Marlese Pacheco A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Michael F. Whiting, Chair Sven Bradler Seth M. Bybee Steven D. Leavitt Department of Biology Brigham Young University Copyright © 2018 Yelena Marlese Pacheco All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Ecomorph Convergence in Stick Insects (Phasmatodea) with Emphasis on the Lonchodinae of Papua New Guinea Yelena Marlese Pacheco Department of Biology, BYU Master of Science Phasmatodea exhibit a variety of cryptic ecomorphs associated with various microhabitats. Multiple ecomorphs are present in the stick insect fauna from Papua New Guinea, including the tree lobster, spiny, and long slender forms. While ecomorphs have long been recognized in phasmids, there has yet to be an attempt to objectively define and study the evolution of these ecomorphs. -

Phasmid Studies 1 (June & December 1992)

PSG 118, Aretaon asperrimus (Redtenbacher) Paul Jennings, 14, Grenfell Avenue, Sunnybill, Derby, DE3 7JZ. U.K•• Taxonomic and distribution notes by P .E. Bragg. lliustration of male by E. Newman. Key words Phasmida, Aretaon asperrimus, Breeding, Rearing. Classification This species was originally described as Obrimus asperrimus by Redtenbacher in 1906. In 1938 Rehn & Rehn established the new genus Aretaon (1938: 419), with asperrimus as the type species. I have examined the type specimens of this species and A. muscosus Redtenbacher, which are all in Vienna, and I found that the type specimens of A. asperrimus are all adults while those of A. muscosus are all nymphs. A. muscosus is distinguished by having more prominent spines, particularly on the front tibiae and the top of the abdomen. However, having reared A. asperrimus it is clear that nymphs of this genus are very spiny and these spines in particular are reduced when the insect becomes adult. It is therefore quite likely that A. asperrimus and A. muscosus are the same species. This possibility was considered and rejected by Gunther (1935: 123) but as he had not reared them he would not have known that the spines are reduced when the insects become adult. The species in culture is clearly A. asperrimus, however it has smaller spines than the type specimens so clearly the species is variable. The type specimens of A. muscosus are much more spiny than those in culture, I cannot therefore be certain that A. asperrimus and A. muscosus are the same species. As there is a strong possibility that they are the same species, I am listing the published references and distribution records for both species. -

Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny

insects Article Three Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Orestes guangxiensis, Peruphasma schultei, and Phryganistria guangxiensis (Insecta: Phasmatodea) and Their Phylogeny Ke-Ke Xu 1, Qing-Ping Chen 1, Sam Pedro Galilee Ayivi 1 , Jia-Yin Guan 1, Kenneth B. Storey 2, Dan-Na Yu 1,3 and Jia-Yong Zhang 1,3,* 1 College of Chemistry and Life Science, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China; [email protected] (K.-K.X.); [email protected] (Q.-P.C.); [email protected] (S.P.G.A.); [email protected] (J.-Y.G.); [email protected] (D.-N.Y.) 2 Department of Biology, Carleton University, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6, Canada; [email protected] 3 Key Lab of Wildlife Biotechnology, Conservation and Utilization of Zhejiang Province, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua 321004, China * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] Simple Summary: Twenty-seven complete mitochondrial genomes of Phasmatodea have been published in the NCBI. To shed light on the intra-ordinal and inter-ordinal relationships among Phas- matodea, more mitochondrial genomes of stick insects are used to explore mitogenome structures and clarify the disputes regarding the phylogenetic relationships among Phasmatodea. We sequence and annotate the first acquired complete mitochondrial genome from the family Pseudophasmati- dae (Peruphasma schultei), the first reported mitochondrial genome from the genus Phryganistria Citation: Xu, K.-K.; Chen, Q.-P.; Ayivi, of Phasmatidae (P. guangxiensis), and the complete mitochondrial genome of Orestes guangxiensis S.P.G.; Guan, J.-Y.; Storey, K.B.; Yu, belonging to the family Heteropterygidae. We analyze the gene composition and the structure D.-N.; Zhang, J.-Y. -

Stick Insects Fact Sheet

Stick Insects Fact Sheet Female Titan Stick Insect. Image: QM, Jeff Wright. Introduction Biology Stick and leaf insects, scientifically known as phasmids, Females lay eggs one at a time, often with a flick of their are among the largest of all insects in the world. At 26 cm, abdomens to throw the egg some distance. An individual the Titan Stick Insect (Acrophylla titan) is the longest of female drops eggs at a rate of one to several per day and all Australian insects. Phasmids have perfected the art of she can produce between 100 and 1,300 eggs in her life- camouflage. Some resemble sticks and foliage so closely time. They fall to the ground and lie in the leaf litter. they even feature false buds, thorns and ragged leaf-like flanges. Small wonder they are rarely seen except after storms when they are blown out of threes and shrubs. Phasmids are sometimes confused with a different group of insects, the mantids. Also called Praying Mantids, these are predators with large, spiny front legs, held folded ready to strike and grasp prey. In contrast, Phasmids are herbivores (plant-eaters) with simple front legs that are similar in size and structure to their other legs. A variety of insect eggs. (on left). An ant carrying a stick insect egg (on right). Images: QM, Jeff Wright. All stick insects feed on fresh leaves. Some browse on a wide variety of trees and shrubs but others are fussy, eating only a limited range of host plants that are often closely Stick insect eggs are generally oval, and superficially seed- related to each other. -

Phasmida (Stick and Leaf Insects)

● Phasmida (Stick and leaf insects) Class Insecta Order Phasmida Number of families 8 Photo: A leaf insect (Phyllium bioculatum) in Japan. (Photo by ©Ron Austing/Photo Researchers, Inc. Reproduced by permission.) Evolution and systematics Anareolatae. The Timematodea has only one family, the The oldest fossil specimens of Phasmida date to the Tri- Timematidae (1 genus, 21 species). These small stick insects assic period—as long ago as 225 million years. Relatively few are not typical phasmids, having the ability to jump, unlike fossil species have been found, and they include doubtful almost all other species in the order. It is questionable whether records. Occasionally a puzzle to entomologists, the Phasmida they are indeed phasmids, and phylogenetic research is not (whose name derives from a Greek word meaning “appari- conclusive. Studies relating to phylogeny are scarce and lim- tion”) comprise stick and leaf insects, generally accepted as ited in scope. The eggs of each phasmid are distinctive and orthopteroid insects. Other alternatives have been proposed, are important in classification of these insects. however. There are about 3,000 species of phasmids, although in this understudied order this number probably includes about 30% as yet unidentified synonyms (repeated descrip- Physical characteristics tions). Numerous species still await formal description. Stick insects range in length from Timema cristinae at 0.46 in (11.6 mm) to Phobaeticus kirbyi at 12.9 in (328 mm), or 21.5 Extant species usually are divided into eight families, in (546 mm) with legs outstretched. Numerous phasmid “gi- though some researchers cite just two, based on a reluctance ants” easily rank as the world’s longest insects. -

Goliath Stick Insect

Husbandry Manual for Eurycnema goliath Tara Bearman Husbandry Manual for Goliath Stick Insect Eurycnema goliath (Gray, 1834) (Insecta: Phasmatidae) Compiled by: Tara Bearman Date of Preparation: 2007 Western Sydney Institute of TAFE, Richmond Course Name and Number: 1068 Certificate III –Captive Animals Lecturer: Graeme Phipps 1 Husbandry Manual for Eurycnema goliath Tara Bearman TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 6 2 TAXONOMY ....................................................................................................................................... 7 2.1 NOMENCLATURE............................................................................................................................. 7 2.2 SUBSPECIES................................................................................................................................... 7 2.3 RECENT SYNONYMS ....................................................................................................................... 7 2.4 OTHER COMMON NAMES ................................................................................................................ 7 3 NATURAL HISTORY........................................................................................................................ 8 3.1 MORPHOMETRICS........................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Mass and -

About the Book the Format Acknowledgments

About the Book For more than ten years I have been working on a book on bryophyte ecology and was joined by Heinjo During, who has been very helpful in critiquing multiple versions of the chapters. But as the book progressed, the field of bryophyte ecology progressed faster. No chapter ever seemed to stay finished, hence the decision to publish online. Furthermore, rather than being a textbook, it is evolving into an encyclopedia that would be at least three volumes. Having reached the age when I could retire whenever I wanted to, I no longer needed be so concerned with the publish or perish paradigm. In keeping with the sharing nature of bryologists, and the need to educate the non-bryologists about the nature and role of bryophytes in the ecosystem, it seemed my personal goals could best be accomplished by publishing online. This has several advantages for me. I can choose the format I want, I can include lots of color images, and I can post chapters or parts of chapters as I complete them and update later if I find it important. Throughout the book I have posed questions. I have even attempt to offer hypotheses for many of these. It is my hope that these questions and hypotheses will inspire students of all ages to attempt to answer these. Some are simple and could even be done by elementary school children. Others are suitable for undergraduate projects. And some will take lifelong work or a large team of researchers around the world. Have fun with them! The Format The decision to publish Bryophyte Ecology as an ebook occurred after I had a publisher, and I am sure I have not thought of all the complexities of publishing as I complete things, rather than in the order of the planned organization. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

2008/2009 Annual Report Australian

The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP Premier and Minister for the Arts Sir, In accordance with the provisions of the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983 we have pleasure in submitting this report of the activities of the Australian Museum Trust for the financial year ended 30 June 2009 for presentation to Parliament. On behalf of the Australian Museum Trust, Brian Sherman, AM President of the Trust Frank Howarth Secretary of the Trust Australian Museum Annual Report 2008–2009 iii MINISTER AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM The Hon. Nathan Rees, MP 6 College Street Sydney NSW 2010 Premier and Minister for the Arts Open daily 9.30 am – 5.00 pm (except 25 December) GOVERNANCE t 02 9320 6000 f 02 9320 6050 The Museum is governed by a Trust [email protected] established under the Australian Museum www.australianmuseum.net.au Trust Act 1975. The Trust currently has eleven members, one of whom must have ADMISSION CHARGES knowledge of, or experience in, science, one of whom must have knowledge of, or General Museum entry experience in, education and one of whom Adult $12 must have knowledge of, or experience Child (5 –15 years) $6 in, Australian Indigenous culture. Trustees are appointed by the Governor on the Concession $8 recommendation of the Minister for a Family (one adult, two children) $18 term of up to three years. Trustees may Family (two adults, two children) $30 hold no more than three terms. Vacancies Each additional child $3 may be filled by the Governor on the recommendation of the Minister. -

Analysis of the Stick Insect (Clitarchus Hookeri) Genome Reveals a High Repeat Content and Sex- Biased Genes Associated with Reproduction Chen Wu1,2,3* , Victoria G

Wu et al. BMC Genomics (2017) 18:884 DOI 10.1186/s12864-017-4245-x RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Assembling large genomes: analysis of the stick insect (Clitarchus hookeri) genome reveals a high repeat content and sex- biased genes associated with reproduction Chen Wu1,2,3* , Victoria G. Twort1,2,4, Ross N. Crowhurst3, Richard D. Newcomb1,3 and Thomas R. Buckley1,2 Abstract Background: Stick insects (Phasmatodea) have a high incidence of parthenogenesis and other alternative reproductive strategies, yet the genetic basis of reproduction is poorly understood. Phasmatodea includes nearly 3000 species, yet only thegenomeofTimema cristinae has been published to date. Clitarchus hookeri is a geographical parthenogenetic stick insect distributed across New Zealand. Sexual reproduction dominates in northern habitats but is replaced by parthenogenesis in the south. Here, we present a de novo genome assembly of a female C. hookeri and use it to detect candidate genes associated with gamete production and development in females and males. We also explore the factors underlying large genome size in stick insects. Results: The C. hookeri genome assembly was 4.2 Gb, similar to the flow cytometry estimate, making it the second largest insect genome sequenced and assembled to date. Like the large genome of Locusta migratoria,the genome of C. hookeri is also highly repetitive and the predicted gene models are much longer than those from most other sequenced insect genomes, largely due to longer introns. Miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs), absent in the much smaller T. cristinae genome, is the most abundant repeat type in the C. hookeri genome assembly. -

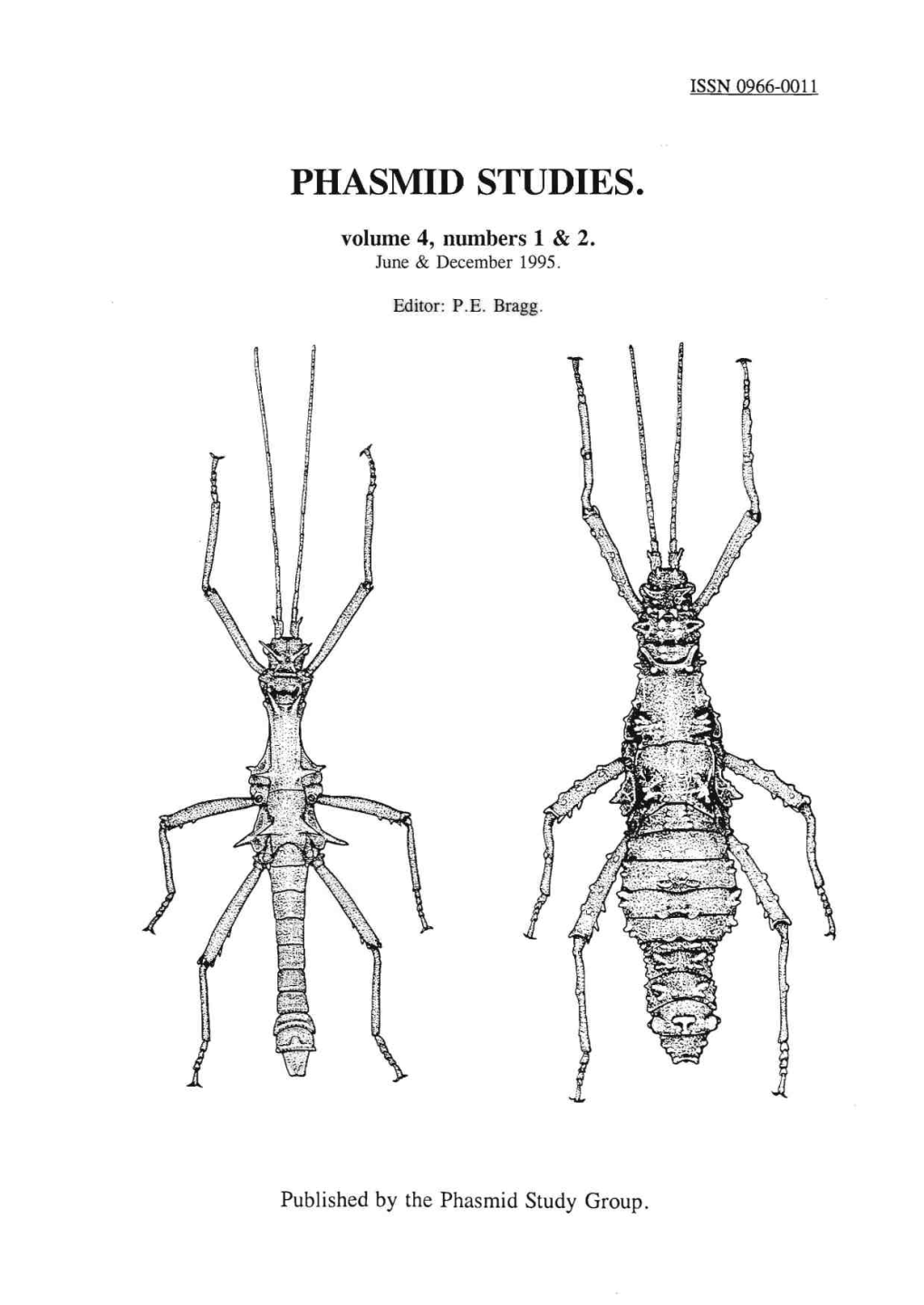

Phasmid Studies ISSN 09660011 Volume 3, Numbers 1 & 2

Phasmid Studies ISSN 09660011 volume 3, numbers 1 & 2. Contents A redefinition of the orientation ter minology of phasmid eggs J.T .C . Sellick . T he evolution and subsequent classification of the Phasmatodea Robert Lind . .. 3 PSG 149, Achrioptera sp. Frank Hennemann . .. 6 Reviews and Abstracts Book Reviews 12 Journal Review . .. 14 Phasmid Abstracts . 15 PSG 146, Centema hadrillus (Westwood) P.E . Bragg 23 A Check List of Type Species of Phasmid Genera P.E. Bragg 28 The Distribution of Asceles margaritatus in Borneo P.E. Bragg 39 The Phasmid Database: version 1.5 P.E. Bragg 4 1 Reviews and Abstracts Phasmid Abstracts . .. 43 Cover illustration : Echinoclonia exotica (Brunne r), by P. E. Bragg. A redefinition of the orientation terminology of phasmid eggs. J.T.C. Sellick, 31 Regem Street, Kdterin~. Nnrthanl~. U.K. Key words Phasmida, Egg Tanninology, Onemation. The article on Dinophasma gwrigera (Westwood) (Bragg 1993) raised the question of how one determines dorsal and ventral surfaces on eggs in which the micropylar plate circles the egg. In the case of this species (by comparison with other Aschiphasmatinae eggs) it would appear that the dorsal surface has been correetly identified as that bearing the micropyle, since it is typical in eggs of this group that the operculum should be lilted ventrally and the micropylar plate should bear a ventral central stripe. The orientation would be confirmed by examination of the internal plate as indicated below. a a d (0) p p 1 d (c) (d) (e) Figure 1. The egg of Ortttomcrio supcrba (Redtenbacher}, a) dorsal view, b) lateral view, c) internal micropylar plate tlattened out. -

The Biology of the Three Species of Phasmatids (Phasmatodea) Which Occur in Plague Numbers in Forests of Southeastern Australia K

This document has been scanned from hard-copy archives for research and study purposes. Please note not all information may be current. We have tried, in preparing this copy, to make the content accessible to the widest possible audience but in some cases we recognise that the automatic text recognition maybe inadequate and we apologise in advance for any inconvenience this may cause. sL.df /0 fl.u I /4r~ / FORESTRY COMMISSION OF N.S.W. DIVISION OF FOREST MANAGEMENT RESEARCH NOTE No. 20 Published January, 1967 THE BIOLOGY OF THE THREE SPECIES OF PHASMATIDS (PHASMATODEA) WmCH OCCUR IN PLAGUE NUMBERS IN FORESTS OF SOUTHEASTERN AUSTRALIA AUTHORS K. G. CAMPBELL, D.F.C., B.Se.(For.), Dip.For., M.Se. and P. HADLINGTON, B.Se.Agr. G771 ~- Issued under the authority of -J The Hon. J. G. Beale, M.E., M.L.A., Minister for Conservation, New South Wales THE BIOLOGY OF THE THREE SPECIES OF PHASMATIDS (PHASMATODEA) WHICH OCCUR IN PLAGUE NUMBERS IN FORESTS OF SOUTHEASTERN AUSTRALIA K. G. CAMPBELL AND P. HADLINGTON FORESTRY COMMISSION OF N.S.W. INTRODUCTION Most species of the Phasmatodea usually occur in low numbers, but some species have occurred in plagues and in such instances serious defoliation of trees has resulted. Plagues have been recorded from the D.S.A. by Craighead (1950), from Fiji by O'Connor (1949) and from the highland areas of southeastern Australia by various workers. The species involved in the defoliation of the eucalypt forests of southeastern Australia are Podacanthus wilkinsoni Mac!., Didymuria violescens (Leach) and Ctenomorphodes tessulatus (Gray).