American Radio Collection, 1931-1972, Collection (S0256)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back Listeners: Locating Nostalgia, Domesticity and Shared Listening Practices in Contemporary Horror Podcasting

Welcome back listeners: locating nostalgia, domesticity and shared listening practices in Contemporary horror podcasting. Danielle Hancock (BA, MA) The University of East Anglia School of American Media and Arts A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Contents Acknowledgements Page 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? Pages 3-29 Section One: Remediating the Horror Podcast Pages 49-88 Case Study Part One Pages 89 -99 Section Two: The Evolution and Revival of the Audio-Horror Host. Pages 100-138 Case Study Part Two Pages 139-148 Section Three: From Imagination to Enactment: Digital Community and Collaboration in Horror Podcast Audience Cultures Pages 149-167 Case Study Part Three Pages 168-183 Section Four: Audience Presence, Collaboration and Community in Horror Podcast Theatre. Pages 184-201 Case Study Part Four Pages 202-217 Conclusion: Considering the Past and Future of Horror Podcasting Pages 218-225 Works Cited Pages 226-236 1 Acknowledgements With many thanks to Professors Richard Hand and Mark Jancovich, for their wisdom, patience and kindness in supervising this project, and to the University of East Anglia for their generous funding of this project. 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? The origin of this thesis is, like many others before it, born from a sense of disjuncture between what I heard about something, and what I experienced of it. The ‘something’ in question is what is increasingly, and I believe somewhat erroneously, termed as ‘new audio culture’. By this I refer to all scholarly and popular talk and activity concerning iPods, MP3s, headphones, and podcasts: everything which we may understand as being tethered to an older history of audio-media, yet which is more often defined almost exclusively by its digital parameters. -

RUSC Old Time Radio

The RUSC Guide to Old Tim e Radio Contents Introduction ........................................................................... 5 Chapter 1 – Old Time Radio................................................. 7 When was the first radio show broadcast? ............................ 8 AT&T lead the way............................................................ 10 NBC – The Granddaddy..................................................... 11 CBS – The New Kid on the Block...................................... 11 MBS – A different way of doing things.............................. 12 The Microsoft Effect.......................................................... 13 Boom & Bust..................................................................... 13 Where did all the shows go?............................................... 14 Are old radio show fans old?.............................................. 16 Chapter 2 - Old radio show genres ..................................... 17 Comedy ............................................................................. 18 Detective............................................................................ 20 Westerns ............................................................................ 21 Drama................................................................................ 22 Juvenile.............................................................................. 24 Quiz Shows........................................................................ 26 Science Fiction.................................................................. -

Higgs Windows to New Physics Through D= 6 Operators: Constraints

November 19, 2013 Higgs windows to new physics through d = 6 operators: Constraints and one-loop anomalous dimensions J. Elias-Mir´oa;b, J.R. Espinosab;c, E. Massoa;b, A. Pomarola a Dept. de F´ısica, Universitat Aut`onomade Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona b IFAE, Universitat Aut`onomade Barcelona, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona c ICREA, Instituci´oCatalana de Recerca i Estudis Avan¸cats,Barcelona, Spain Abstract The leading contributions from heavy new physics to Higgs processes can be cap- tured in a model-independent way by dimension-six operators in an effective Lagrangian approach. We present a complete analysis of how these contributions affect Higgs cou- plings. Under certain well-motivated assumptions, we find that 8 CP-even plus 3 CP-odd Wilson coefficients parametrize the main impact in Higgs physics, as all other coefficients are constrained by non-Higgs SM measurements. We calculate the most relevant anoma- lous dimensions for these Wilson coefficients, which describe operator mixing from the heavy scale down to the electroweak scale. This allows us to find the leading-log correc- tions to the predictions for the Higgs couplings in specific models, such as the MSSM or composite Higgs, which we find to be significant in certain cases. arXiv:1308.1879v2 [hep-ph] 17 Nov 2013 1 Introduction The resonance observed at around 125 GeV at the LHC [1] has properties consistent with the Standard Model Higgs boson. More precise measurements of its couplings will hopefully provide information on the origin of electroweak symmetry breaking (EWSB) in the Standard Model (SM). All natural mechanisms proposed for EWSB introduce new physics at some scale Λ, not far from the TeV scale, that generates deviations in the SM Higgs physics. -

Eugenio Maria De Hostos Charter School

Charter Schools Institute State University of New York EUGENIO MARIA DE HOSTOS CHARTER SCHOOL FINAL CHARTERED AGREEMENT Sec. 2852(5) Submission to the Board of Regents VOLUME > OF REDACTED COP 74 North Pearl Street, 4m Floor, Albany, NY 12207 tel: (518) 433-8277 fax: (518) 427-6510 e-mail: [email protected] www.newyorkcharters.org OMU NO. 1646-0047 Form 990 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax Under section 501(c) of the internal Revenue Code (except black lung benefit 97 trust or private foundation) or section 4847(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust TMaFotmla 0*#*m**of@*Tmm*y OpMtoPutofle torn* Rtwnw Swvica Hetr. reorganization may have to uso a copy rfthb return to salty stata reportw InmpmcUon A For tha 1997 calendar year, OH tax year period beginning /^^r^. / , 1997, and ending Af*,*-ts.A*B I . 19 ?g B Chock* C Ntm* of organization MentmcaBon number UMIRS O Change of iddren taMor ^e.*. W4~ >c D Initial return printer Numbar and atroat (or P.O. box if mall la not daUvarad to street addreaa) Room/suits DP*. DfinaJ return City or town, stata or country, and ZIP+4 D Amandad return Inttrue- F Check »- D if exemption application (raqulrad aJao for Stata reporting) /V£&S a pending Q Type of organization—*>^ Exempt under section 501 (c)( 3 ) + (Insert number) OR • • section 4947(aK1) nonexempt charitable trust Note: Section 501(c)(3) exempt onjanfeanoni and 4947(a)(1) nonaxempt charitable trusts MUST attach a completed Schedule A (Fom 990). H|a) la thia a group return filed for affiliates? .• Yes IS No I If either box In His checked "Yea," enter fouwllgit group exemption number (GEN) • j/.J.d (b) If "Yea." enter the number of efflUatee for whlchthia return la filed:. -

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis

Perkins, Anthony (1932-1992) by Tina Gianoulis Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2007 glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com The life and career of actor Anthony Perkins seems almost like a movie script from the times in which he lived. One of the dark, vulnerable anti-heroes who gained popularity during Hollywood's "post-golden" era, Perkins began his career as a teen heartthrob and ended it unable to escape the role of villain. In his personal life, he often seemed as tortured as the troubled characters he played on film, hiding--and perhaps despising--his true nature while desperately seeking happiness and "normality." Perkins was born on April 4, 1932 in New York City, the only child of actor Osgood Perkins and Janet Esseltyn Rane. His father died when he was only five, and Perkins was reared by his strong-willed and possibly abusive mother. He followed his father into the theater, joining Actors Equity at the age of fifteen and working backstage until he got his first acting roles in summer stock productions of popular plays like Junior Miss and My Sister Eileen. He continued to hone his acting skills while attending Rollins College in Florida, performing in such classics as Harvey and The Importance of Being Earnest. Perkins was an unhappy young man, and the theater provided escape from his loneliness and depression. "There was nothing about me I wanted to be," he told Mark Goodman in a People Weekly interview. "But I felt happy being somebody else." During his late teens, Perkins went to Hollywood and landed his first film role in the 1953 George Cukor production, The Actress, in which he appeared with Spencer Tracy. -

Completeandleft

MEN WOMEN 1. Adam Ant=English musician who gained popularity as the Amy Adams=Actress, singer=134,576=68 AA lead singer of New Wave/post-punk group Adam and the Amy Acuff=Athletics (sport) competitor=34,965=270 Ants=70,455=40 Allison Adler=Television producer=151,413=58 Aljur Abrenica=Actor, singer, guitarist=65,045=46 Anouk Aimée=Actress=36,527=261 Atif Aslam=Pakistani pop singer and film actor=35,066=80 Azra Akin=Model and actress=67,136=143 Andre Agassi=American tennis player=26,880=103 Asa Akira=Pornographic act ress=66,356=144 Anthony Andrews=Actor=10,472=233 Aleisha Allen=American actress=55,110=171 Aaron Ashmore=Actor=10,483=232 Absolutely Amber=American, Model=32,149=287 Armand Assante=Actor=14,175=170 Alessandra Ambrosio=Brazilian model=447,340=15 Alan Autry=American, Actor=26,187=104 Alexis Amore=American pornographic actress=42,795=228 Andrea Anders=American, Actress=61,421=155 Alison Angel=American, Pornstar=642,060=6 COMPLETEandLEFT Aracely Arámbula=Mexican, Actress=73,760=136 Anne Archer=Film, television actress=50,785=182 AA,Abigail Adams AA,Adam Arkin Asia Argento=Actress, film director=85,193=110 AA,Alan Alda Alison Armitage=English, Swimming=31,118=299 AA,Alan Arkin Ariadne Artiles=Spanish, Model=31,652=291 AA,Alan Autry Anara Atanes=English, Model=55,112=170 AA,Alvin Ailey ……………. AA,Amedeo Avogadro ACTION ACTION AA,Amy Adams AA,Andre Agasi ALY & AJ AA,Andre Agassi ANDREW ALLEN AA,Anouk Aimée ANGELA AMMONS AA,Ansel Adams ASAF AVIDAN AA,Army Archerd ASKING ALEXANDRIA AA,Art Alexakis AA,Arthur Ashe ATTACK ATTACK! AA,Ashley -

The KIRBY RESIDENTS

the PINECONEThe Magazine of Kirby Pines Retirement Community • January 2015 | V. 33 | I. 1 KIRBY RESIDENTS HELPING CLEAN UP MEMPHIS Senior Fit Test | Opportunity Knocks | Resident Spotlight: Catherine Prewett | Social Scenes A Look Back at a Wonderful Year Kirby Pines Retirement Community at Kirby Pines is managed by Happy New Year, everyone! Each hours should once again surpass the year seems to get here quicker, with previous year’s total because of the little difference from the previous year. expanded hours due to the move of the However, 2015 will not be one of those Blossom Shop to the second floor. BOARD OF DIRECTORS years. Before I begin to write about improvements made in 2014, let me thank In early summer Kirby Pines was once Dr. James Latimer, Chairman each of you for another wonderful year of again named the area’s Best Retirement Mr. Rudy Herzke, President service at Kirby Pines. Community, an honor bestowed upon Mr. Berry Terry, Secretary/Treasurer Kirby for eight consecutive years now. Mr. Larry Braughton Rev. Richard Coons In 2014 we made several No other retirement community in our improvements in our meal service venues tri-state area has been able to earn this Mr. Jim Ethridge Dr. Fred Grogan and one of the most successful was the public recognition. With the unique event Ms. Mary Ann Hodges creation of a Live Action Station in the Cheryl created inviting area merchants to Mr. Boyd Rhodes, Jr. dining room. Originally done as a chef participate in our first Carousel of Shops, special, the Live Action Station proved to we should be able to hold on to our top RCA STAFF be such a hit that we went from once a spot again in 2015. -

Alfred L. Werker Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Alfred L. Werker 电影 串行 (大全) The Pioneer Scout https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-pioneer-scout-3388920/actors Heartbreak https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/heartbreak-3129041/actors Gateway https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gateway-11612443/actors Three Hours to Kill https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/three-hours-to-kill-13425839/actors Hello, Sister! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/hello%2C-sister%21-1466234/actors The Last Posse https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-last-posse-15207947/actors Canyon Crossroads https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/canyon-crossroads-15651028/actors Moon Over Her Shoulder https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/moon-over-her-shoulder-16999616/actors My Pal Wolf https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/my-pal-wolf-18152840/actors Advice to the Lovelorn https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/advice-to-the-lovelorn-18204858/actors We Have Our Moments https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/we-have-our-moments-20004180/actors City Girl https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/city-girl-20082607/actors Whispering Ghosts https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/whispering-ghosts-20814902/actors Shock https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shock-2084180/actors It Could Happen to You https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/it-could-happen-to-you-21470118/actors The Mad Martindales https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-mad-martindales-21527836/actors News Is Made at Night https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/news-is-made-at-night-21527898/actors -

OLD TIME RADIO MASTER CATALOGUE.Xlsx

1471 PREVIEW THEATER OF THE AIR ZORRO-TO TRAP A FOX 15 VG SYN 744 101ST CHASE AND SANDBORN SHOW ANNIVERSARY SHOW NBC 60 EX COM 2951 15 MINUTES WITH BING CROSBY #1 1ST SONG JUST ONE MORE CHANCE 9/2/1931 8 VG SYN 4068 1949 HEART FUND THE PHIL HARRIS-ALICE FAYE SHOW 00/00/1949 15 VG COM 588 20 QUESTIONS 4/6/1946 30 VG- 592 20 QUESTIONS WET HEN MUT. 30 VG- 2307 2000 PLUS THE ROCKET AND THE SKULL 30 VG- SYN 2308 2000 PLUS A VETRAN COMES HOME 30 VG- SYN 3656 21ST PRECINCT LAST SHOW 4/20/1955 30 VG- COM 4069 A & P GYPSIES 1ST SONG IT'S JUST A MEMORY 00/00/1933 NBC 37 VG+ 1017 A CHRISTMAS PLAY #325 THESE THE HUMBLE (SCRATCHY) 30 G-VG SYN 2003 A DATE WITH JUDY WITH JOSEPH COTTON 2/6/1945 NBC 30 VG COM 938 A DATE WITH JUDY #86 WITH CHARLES BOYER AFRS 30 VG AFRS 2488 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH MARLENA DETRICH 10/15/1942 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2489 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LUCILLE BALL 11/18/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4071 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LYNN BARI 12/16/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 4072 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE ANDREW SISTERS 12/26/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 2490 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH BERT GORDON 12/30/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2491 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH JUDY GARLAND 1/6/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2492 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH HAROLD PERRY 1/20/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4073 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE GREAT GILDERSLEEVE 1/20/1944 NBC 30 VG COM 2493 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH DOROTHY LAMOUR 2/17/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4074 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH HEDDA HOPPER 3/2/1944 NBC 30 VG COM 4075 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH BLONDIE AND DAGWOOD 3/9/1944 NBC 30 VG COM 4076 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH -

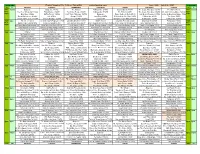

Radioclassics (Siriusxm Ch. 148) Gregbellmedia

SHOW TIME RadioClassics (SiriusXM Ch. 148) gregbellmedia.com June 21st - June 27th, 2021 SHOW TIME PT ET MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY PT ET 9pm 12mid Mary Livingstone B-Day Fibber McGee & Molly I Was A Communist More Peter Lorre B-Day Frontier Town 10/24/52 Dimension X Family Theatre 7/8/53 9pm 12mid Prev Jack Benny Prgm 2/23/47 From October 10th, 1944 For The FBI 5/7/52 on Fred Allen Show 1/3/43 The Cisco Kid 3/31/53 "The Embassy" 6/3/50 CBS Radio Workshp 8/17/56 Prev Night Night Jack Benny Prgm 9/21/52 Burns & Allen Show 5/18/43 Gangbusters 8/16/52 on Duffy's Tavern 10/19/43 Broadway's My Beat 4/21/50 X-Minus One 8/29/57 Broadway Is My Beat Dragnet Big Guilt 11/23/52 Black Museum 11/25/52 Casey, Crime Photog 1/8/48 Inner Sanctum 3/7/43 Calling All Cars 9/7/37 Burns & Allen 3/27/47 From Dec. 31st, 1949 Big Town 6/18/42 Suspense 6/14/45 Sherlock Holmes 3/31/47 Suspense 7/20/44 Great Gildersleeve 3/1/50 Gunsmoke Belle's Back 9/9/56 11pm 2am Phil Harris Birthday (1) Phil Harris Birthday (2) Mr District Attorney 11/30/52 Paul Frees Birthday (1) Yours Truly, Johnny Boston Blackie 77th Annv Lux Radio's (9/26/38) 11pm 2am Prev Harris & Faye 12/11/53 From Harris & Faye Show Sam Spade 8/2/48 The Whistler 5/22/49 Dollar Marathon Jan 1956 w/ Chester Morris 7/28/44 Seven Keys To Baldpate Prev Night Night Harris & Faye 10/19/52 11/13/49 & 1/13/52 Dimension X 7/12/51 EscapeHouseUsher 10/22/47 The Flight Six Matter w/ Dick Kollmar 1/29/46 with Jack & Mary Benny Harris & Faye 1/15/50 On Suspense 5/10/51 X Minus One 4/24/57 -

Radioclassics.Com June 28Th

SHOW TIME RadioClassics (Ch. 148 on SiriusXM) radioclassics.com June 28th - July 4th, 2021 SHOW TIME PT ET MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY SUNDAY PT ET 9pm 12mid Suspense Suspense 9/16/42 The Whistler X-Minus One 2/15/56 Boston Blackie 7/9/46 The Couple Next Door 1/21/58 The Aldrich Family 9pm 12mid Prev You Were Wonderful 11/9/44 Philip Marlowe 7/28/51 Two Smart People 9/30/51 X-Minus One 7/14/55 The Falcon 6/20/51 The Couple Next Door 1/22/58 Mr. Aldrich Cooks Dinner 12/8/48 Prev Night Night Blue Eyes 8/29/46 Duffy's Tavern 1/25/44 Can't Trust A Stranger 7/27/52 Gunsmoke Fibber McGee & Molly 9/5/39 Jack Benny Program 2/17/52Detention Or Basketball Game 10/28/48 Great Gildersleeve 9/18/46 Life of Riley Escape 7/12/53 Last Fling 2/20/54 Phil Harris & Alice Faye 3/2/52 X-Minus One 4/3/56 The Chase 5/4/52 Jack Benny Program 11/16/47 Cissie's Marriage 3/24/50 I Was Communist/FBI 10/29/52 Cara 5/1/54 Going To Vegas Without Frankie X-Minus One 1/23/57 X-Minus One 6/27/57 11pm 2am The Green Hornet Screen Director's Playhouse 3/31/50 Our Miss Brooks 11/13/49 Duffy's Tavern Columbia Presents Corwin Dimension X 5/13/50 Fort Laramie 9/9/56 11pm 2am Prev Murder Trips A Rat 9/19/42 Academy Award Theatre Jack Carson Show 4/2/47 Susan Hayward & Frank Buck 7/25/43American Trilogy Carl Sandberg 6/6/44 Inner Sanctum Mysteries Gunsmoke 6/15/58 Prev Night Night Green Hornet Goes Underground 10/3/43Hold Back The Dawn 7/31/46 Lum & Abner 1/19/43 Guest: Shelley Winters 2/16/50 An American Gallery 1960s Death In The Depths 2/6/45 Command Performance -

744 101St Chase and Sandborn Show Anniversary Show

744 101ST CHASE AND SANDBORN SHOW ANNIVERSARY SHOW NBC 60 EX COM 5008 10-2-4 RANCH #153 1ST SONG HOME ON THE RANGE CBS 15 EX COM 5009 10-2-4 RANCH #154 1ST SONG UNTITLED SONG CBS 15 EX COM 5010 10-2-4 RANCH #155 1ST SONG BY THE SONS OF THE PIONEERS CBS 15 EX COM 5011 10-2-4 RANCH #156 1ST SONG KEEP AN EYE ON YOUR HEART CBS 15 EX COM 2951 15 MINUTES WITH BING CROSBY #1 1ST SONG JUST ONE MORE CHANCE 9/2/1931 8 VG SYN 4068 1949 HEART FUND THE PHIL HARRIS-ALICE FAYE SHOW 00/00/1949 15 VG COM 588 20 QUESTIONS 4/6/1946 30 VG- 246 20 QUESTIONS #135 12/1/48 AFRS 30 VG AFRS 247 20 QUESTIONS #137 1/8/1949 AFRS 30 VG AFRS 592 20 QUESTIONS WET HEN MUT. 30 VG- 2307 2000 PLUS THE ROCKET AND THE SKULL 30 VG- SYN 2308 2000 PLUS A VETRAN COMES HOME 30 VG- SYN 4069 A & P GYPSIES 1ST SONG IT'S JUST A MEMORY 00/00/1933 NBC 37 VG+ 1017 A CHRISTMAS PLAY #325 THESE THE HUMBLE (SCRATCHY) 30 G-VG SYN 2003 A DATE WITH JUDY WITH JOSEPH COTTON 2/6/1945 NBC 30 VG COM 938 A DATE WITH JUDY #86 WITH CHARLES BOYER AFRS 30 VG AFRS 2488 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH MARLENA DETRICH 10/15/1942 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2489 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LUCILLE BALL 11/18/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4071 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH LYNN BARI 12/16/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 4072 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE ANDREW SISTERS 12/26/1943 NBC 30 VG COM 2490 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH BERT GORDON 12/30/1943 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2491 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH JUDY GARLAND 1/6/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 2492 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH HAROLD PERRY 1/20/1944 NBC 30 VG+ COM 4073 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO WITH THE GREAT GILDERSLEEVE 1/20/1944 NBC