Principles of Star Formation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effect of the Solar Wind Density on the Evolution of Normal and Inverse Coronal Mass Ejections S

A&A 632, A89 (2019) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201935894 & c ESO 2019 Astrophysics Effect of the solar wind density on the evolution of normal and inverse coronal mass ejections S. Hosteaux, E. Chané, and S. Poedts Centre for mathematical Plasma-Astrophysics (CmPA), Celestijnenlaan 200B, KU Leuven, 3001 Leuven, Belgium e-mail: [email protected] Received 15 May 2019 / Accepted 11 September 2019 ABSTRACT Context. The evolution of magnetised coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and their interaction with the background solar wind leading to deflection, deformation, and erosion is still largely unclear as there is very little observational data available. Even so, this evolution is very important for the geo-effectiveness of CMEs. Aims. We investigate the evolution of both normal and inverse CMEs ejected at different initial velocities, and observe the effect of the background wind density and their magnetic polarity on their evolution up to 1 AU. Methods. We performed 2.5D (axisymmetric) simulations by solving the magnetohydrodynamic equations on a radially stretched grid, employing a block-based adaptive mesh refinement scheme based on a density threshold to achieve high resolution following the evolution of the magnetic clouds and the leading bow shocks. All the simulations discussed in the present paper were performed using the same initial grid and numerical methods. Results. The polarity of the internal magnetic field of the CME has a substantial effect on its propagation velocity and on its defor- mation and erosion during its evolution towards Earth. We quantified the effects of the polarity of the internal magnetic field of the CMEs and of the density of the background solar wind on the arrival times of the shock front and the magnetic cloud. -

Predicting the Magnetic Vectors Within Coronal Mass Ejections Arriving at Earth: 2

Space Weather RESEARCH ARTICLE Predicting the magnetic vectors within coronal mass ejections 10.1002/2015SW001171 arriving at Earth: 1. Initial architecture Key Points: N. P.Savani1,2, A. Vourlidas1, A. Szabo2,M.L.Mays2,3, I. G. Richardson2,4, B. J. Thompson2, • First architectural design to predict A. Pulkkinen2,R.Evans5, and T. Nieves-Chinchilla2,3 a CME’s magnetic vectors (with eight events) 1 2 • Modified Bothmer-Schwenn CME Goddard Planetary Heliophysics Institute (GPHI), University of Maryland, Baltimore County, Maryland, USA, NASA 3 initiation rule to improve reliability Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA, Institute for Astrophysics and Computational Sciences (IACS), of chirality Catholic University of America, Washington, District of Columbia, USA, 4Department of Astronomy, University of • CME evolution seen by remote Maryland, College Park, Maryland, USA, 5College of Science, George Mason University, Fairfax, Vancouver, USA sensing triangulation is important for forecasting Abstract The process by which the Sun affects the terrestrial environment on short timescales is Correspondence to: predominately driven by the amount of magnetic reconnection between the solar wind and Earth’s N. P. Savani, magnetosphere. Reconnection occurs most efficiently when the solar wind magnetic field has a southward [email protected] component. The most severe impacts are during the arrival of a coronal mass ejection (CME) when the magnetosphere is both compressed and magnetically connected to the heliospheric environment. Citation: Unfortunately, forecasting magnetic vectors within coronal mass ejections remain elusive. Here we report Savani, N. P., A. Vourlidas, A. Szabo, M.L.Mays,I.G.Richardson,B.J. how, by combining a statistically robust helicity rule for a CME’s solar origin with a simplified flux rope Thompson, A. -

Predictability of the Variable Solar-Terrestrial Coupling Ioannis A

https://doi.org/10.5194/angeo-2020-94 Preprint. Discussion started: 26 January 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Predictability of the variable solar-terrestrial coupling Ioannis A. Daglis1,15, Loren C. Chang2, Sergio Dasso3, Nat Gopalswamy4, Olga V. Khabarova5, Emilia Kilpua6, Ramon Lopez7, Daniel Marsh8,16, Katja Matthes9,17, Dibyendu Nandi10, Annika Seppälä11, Kazuo Shiokawa12, Rémi Thiéblemont13 and Qiugang Zong14 5 1Department of Physics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, 15784 Athens, Greece 2Department of Space Science and Engineering, Center for Astronautical Physics and Engineering, National Central University, Taiwan 3Department of Physics, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, Argentina 10 4Heliophysics Science Division, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA 5Solar-Terrestrial Department, Pushkov Institute of Terrestrial Magnetism, Ionosphere and Radio Wave Propagation of RAS (IZMIRAN), Moscow, 108840, Russia 6Department of Physics, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland 7Department of Physics, University of Texas at Arlington, Arlington, TX 76019, USA 15 8National Center for Atmospheric Research, Boulder, CO 80305, USA 9GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, Kiel, Germany 10IISER, Kolkata, India 11Department of Physics, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand 12Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan 20 13LATMOS, Universite Pierre et Marie Curie, Paris, France 14School of Earth and Space Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China 15Hellenic Space Center, Athens, Greece 16Faculty of Engineering and Physical Sciences, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK 17Christian-Albrechts Universität, Kiel, Germany 25 Correspondence to: Ioannis A. Daglis ([email protected]) Abstract. In October 2017, the Scientific Committee on Solar-Terrestrial Physics (SCOSTEP) Bureau established a 30 committee for the design of SCOSTEP’s Next Scientific Program (NSP). -

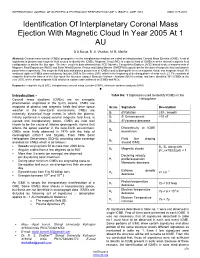

Identification of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection with Magnetic Cloud in Year 2005 at 1 AU

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 3, ISSUE 6, JUNE 2014 ISSN 2277-8616 Identification Of Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection With Magnetic Cloud In Year 2005 At 1 AU D.S.Burud, R .S. Vhatkar, M. B. Mohite Abstract: Coronal mass ejection (CMEs) propagate in to the interplanetary medium are called as Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejection (ICME). A set of signatures in plasma and magnetic field is used to identify the ICMEs. Magnetic Cloud (MC) is a special kind of ICMEs in which internal magnetic field configuration is similar like flux rope. We have used the data obtained from ACE Advance Composition Explorer (ACE) based in-situ measurements of Magnetic Field Experiment (MAG) and Solar Wind Electron, Proton and Alpha Monitor (SWEPAM) experiment for the data of magnetic field and plasma parameters respectively. The magnetic field data and plasma parameters of ICMEs used to distinguish them as magnetic cloud, non magnetic cloud. We analyzed eighteen ICMEs observed during January 2005 to December 2005, which is the beginning of declining phase of solar cycle 23. The analysis of magnetic field in the frames of the flux ropes like structure using a Minimum Variance Analysis (MVA) method, and have identified 30% ICMEs in the year 2005, which shows magnetic field rotation in a plane and confirmed as ICMEs with MCs. Keywords: magnetic cloud (MC), interplanetary coronal mass ejection (ICME), minimum variance analysis (MVA). ———————————————————— Introduction:- Table No: 1 Signatures used to identify ICMEs in the Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are an energetic Heliosphere phenomenon originated in the Sun‘s corona, CMEs are eruptions of plasma and magnetic fields that drive space Sr.no. -

Ten Years of PAMELA in Space

Ten Years of PAMELA in Space The PAMELA collaboration O. Adriani(1)(2), G. C. Barbarino(3)(4), G. A. Bazilevskaya(5), R. Bellotti(6)(7), M. Boezio(8), E. A. Bogomolov(9), M. Bongi(1)(2), V. Bonvicini(8), S. Bottai(2), A. Bruno(6)(7), F. Cafagna(7), D. Campana(4), P. Carlson(10), M. Casolino(11)(12), G. Castellini(13), C. De Santis(11), V. Di Felice(11)(14), A. M. Galper(15), A. V. Karelin(15), S. V. Koldashov(15), S. Koldobskiy(15), S. Y. Krutkov(9), A. N. Kvashnin(5), A. Leonov(15), V. Malakhov(15), L. Marcelli(11), M. Martucci(11)(16), A. G. Mayorov(15), W. Menn(17), M. Mergè(11)(16), V. V. Mikhailov(15), E. Mocchiutti(8), A. Monaco(6)(7), R. Munini(8), N. Mori(2), G. Osteria(4), B. Panico(4), P. Papini(2), M. Pearce(10), P. Picozza(11)(16), M. Ricci(18), S. B. Ricciarini(2)(13), M. Simon(17), R. Sparvoli(11)(16), P. Spillantini(1)(2), Y. I. Stozhkov(5), A. Vacchi(8)(19), E. Vannuccini(1), G. Vasilyev(9), S. A. Voronov(15), Y. T. Yurkin(15), G. Zampa(8) and N. Zampa(8) (1) University of Florence, Department of Physics, I-50019 Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, Italy (2) INFN, Sezione di Florence, I-50019 Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, Italy (3) University of Naples “Federico II”, Department of Physics, I-80126 Naples, Italy (4) INFN, Sezione di Naples, I-80126 Naples, Italy (5) Lebedev Physical Institute, RU-119991 Moscow, Russia (6) University of Bari, I-70126 Bari, Italy (7) INFN, Sezione di Bari, I-70126 Bari, Italy (8) INFN, Sezione di Trieste, I-34149 Trieste, Italy (9) Ioffe Physical Technical Institute, RU-194021 St. -

Diapositiva 1

PAMELAPAMELA SpaceSpace MissionMission FirstFirst ResultsResults inin CosmicCosmic RaysRays Piergiorgio Picozza INFN & University of Rome “ Tor Vergata” , Italy Virtual Institute of Astroparticle Physics June 20, 2008 Robert L. Golden ANTIMATTERANTIMATTER Antimatter Lumps Trapped in our Galaxy antiparticles Antimatter and Dark Matter Research Wizard Collaboration -- BESS (93, 95, 97, 98, 2000) - MASS – 1,2 (89,91) - - Heat (94, 95, 2000) --TrampSI (93) - IMAX (96) -CAPRICE (94, 97, 98) - BESS LDF (2004, 2007) - ATIC (2001, 2003, 2005) - AMS-01 (98) AntimatterAntimatter “We must regard it rather an accident that the Earth and presumably the whole Solar System contains a preponderance of negative electrons and positive protons. It is quite possible that for some of the stars it is the other way about” P. Dirac, Nobel lecture (1933) 4% 23% 73% Signal (supersymmetry)… … and background )(GLAST AMS-02 pCR p+ → ISM p + p+ + p p + + + +pCR pISM →π → μ e → →π0 → γγ e+ → e − Another possible scenario: KK Dark Matter Lightest Kaluza-Klein Particle (LKP): B(1) Bosonic Dark Matter: fermionic final states no longer helicity suppressed. e+e- final states directly produced. As in the neutralino case there are 1-loop processes that produces monoenergetic γγin the final state. P Secondary production (upper and lower limits) Simon et al. ApJ 499 (1998) 250. from χχ Secondary annihilation production (Primary Bergström et production al. ApJ 526 m(c) = 964 (1999) 215 GeV) Ullio : astro- ph/9904086 AntiprotonAntiproton--ProtonProton RatioRatio Potgieter at -

Properties and Geoeffectiveness of Magnetic Clouds During Solar Cycles 23 and 24 N. Gopalswamy1, S. Yashiro1,2, H. Xie1,2, S. Akiyama1,2, and P

Properties and Geoeffectiveness of Magnetic Clouds during Solar Cycles 23 and 24 N. Gopalswamy1, S. Yashiro1,2, H. Xie1,2, S. Akiyama1,2, and P. Mäkelä1,2 1Solar Physics Laboratory, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771 2The Catholic University of America, Washington DC 20064 Corresponding author email: [email protected] Key points • Properties of magnetic clouds in cycle 23 and 24 are significantly different • Anomalous expansion of CMEs cause the magnetic dilution in clouds • Reduced magnetic content and speed of clouds lead to low geoeffectiveness • Accepted for publication in J. Geophys. Res. October 2, 2015 1 Abstract We report on a study that compares the properties of magnetic clouds (MCs) during the first 73 months of solar cycles 23 and 24 in order to understand the weak geomagnetic activity in cycle 24. We find that the number of MCs did not decline in cycle 24, although the average sunspot number is known to have declined by ~40%. Despite the large number of MCs, their geoeffectiveness in cycle 24 was very low. The average Dst index in the sheath and cloud portions in cycle 24 was -33 nT and -23 nT, compared to -66 nT and -55 nT, respectively in cycle 23. One of the key outcomes of this investigation is that the reduction in the strength of geomagnetic storms as measured by the Dst index is a direct consequence of the reduction in the factor VBz (the product of the MC speed and the out-of-the-ecliptic component of the MC magnetic field). The reduction in MC-to-ambient total pressure in cycle 24 is compensated for by the reduction in the mean MC speed, resulting in the constancy of the dimensionless expansion rate at 1 AU. -

Magnetic Cloud Field Intensities and Solar Wind Velocities

GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH LETTERS, VOL. 25, NO. 7, PAGES 963-966, APRIL 1, 1998 Magnetic cloud field intensitiesand solar wind velocities W. D. Gonzalez, A. L. (",Idade Go•zalez, A. Da.1La,go Institute Nacional de PesquisasEspaciais, She Jos6dos Campos, SP, Brasil B. T. Tsurutani, .1. K. Arballo, G. K. La,klfina,B. Butt, C. M. SpacePla.sma Physics, Jet PropulsionLaboratory, C, Mifornia Institute of Technology,Pasadena, S.-T. Wu (',enterfor SpacePlasma and AeronomicResearch, and Departmentof Mechanicaland Aerospace Engineering,The 11niversityof Alabamain Huntsville,Huntsville Abstract. For the sets of magnetic clo•ds studied in this work [Dungcy,1961 ]. In the aboveexpression, v is the so- we have shown the existence of a relationship between lar wind velocity and Bs is the southward component their peak magneticfield strength and peak velocity of the interplanetary magnetic field (IMF). Gonzalez values, with a clear tendencythat, cloudswhich move and Tsurutani [1987]have establishedempirically that at,higher speeds also possess higher core magnetic field the interplanetary electric field must be greater than 5 strengths.This resultsuggests a possibleintrinsic prop- mV/m for longerthan 3 hoursto createa Dst _• --100 erty of magneticclouds and alsoimplies a geophysical nT magnetic storm. This correspondsto a southward consequence.The relativelylow field strengthsat low field component larger than 12.5 nT for a solar wind velocitiesis pres•mablythe causeof the lackof intense speedof • 400 km/s. stormsduring low speede. jecta. There is alsoan indi- Although the positive correlation })el,weenfast (',MEs cation that, this type of behavior is peculiar for mag- and magnetic storms have been stressedand is reason- netic clouds, whereas other types of non cloud-driver ably well understood, little attention has been paid to gasevents do not,seem to showa similarrelationship, the opposite question, why don't, slow CMEs lead to at least,for the data studied in this paper. -

Extreme Solar Eruptions and Their Space Weather Consequences Nat

Extreme Solar Eruptions and their Space Weather Consequences Nat Gopalswamy NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, MD 20771, USA Abstract: Solar eruptions generally refer to coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and flares. Both are important sources of space weather. Solar flares cause sudden change in the ionization level in the ionosphere. CMEs cause solar energetic particle (SEP) events and geomagnetic storms. A flare with unusually high intensity and/or a CME with extremely high energy can be thought of examples of extreme events on the Sun. These events can also lead to extreme SEP events and/or geomagnetic storms. Ultimately, the energy that powers CMEs and flares are stored in magnetic regions on the Sun, known as active regions. Active regions with extraordinary size and magnetic field have the potential to produce extreme events. Based on current data sets, we estimate the sizes of one-in-hundred and one-in-thousand year events as an indicator of the extremeness of the events. We consider both the extremeness in the source of eruptions and in the consequences. We then compare the estimated 100-year and 1000-year sizes with the sizes of historical extreme events measured or inferred. 1. Introduction Human society experienced the impact of extreme solar eruptions that occurred on October 28 and 29 in 2003, known as the Halloween 2003 storms. Soon after the occurrence of the associated solar flares and coronal mass ejections (CMEs) at the Sun, people were expecting severe impact on Earth’s space environment and took appropriate actions to safeguard technological systems in space and on the ground. -

ESA Space Weather STUDY Alcatel Consortium

ESA Space Weather STUDY Alcatel Consortium SPACE Weather Parameters WP 2100 Version V2.2 1 Aout 2001 C. Lathuillere, J. Lilensten, M. Menvielle With the contributions of T. Amari, A. Aylward, D. Boscher, P. Cargill and S.M. Radicella 1 2 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 5 2 THE MODELS............................................................................................................................................. 6 2.1 THE SUN 6 2.1.1 Reconstruction and study of the active region static structures 7 2.1.2 Evolution of the magnetic configurations 9 2.2 THE INTERPLANETARY MEDIUM 11 2.3 THE MAGNETOSPHERE 13 2.3.1 Global magnetosphere modelling 14 2.3.2 Specific models 16 2.4 THE IONOSPHERE-THERMOSPHERE SYSTEM 20 2.4.1 Empirical and semi-empirical Models 21 2.4.2 Physics-based models 23 2.4.3 Ionospheric profilers 23 2.4.4 Convection electric field and auroral precipitation models 25 2.4.5 EUV/UV models for aeronomy 26 2.5 METEOROIDS AND SPACE DEBRIS 27 2.5.1 Space debris models 27 2.5.2 Meteoroids models 29 3 THE PARAMETERS ................................................................................................................................ 31 3.1 THE SUN 35 3.2 THE INTERPLANETARY MEDIUM 35 3.3 THE MAGNETOSPHERE 35 3.3.1 The radiation belts 36 3.4 THE IONOSPHERE-THERMOSPHERE SYSTEM 36 4 THE OBSERVATIONS ........................................................................................................................... -

Characteristics of Magnetic Clouds and Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejections Which Cause Intense Geomagnetic Storms

Terr. Atmos. Ocean. Sci., Vol. 24, No. 2, 233-241, April 2013 doi: 10.3319/TAO.2012.09.26.03(SEC) Characteristics of Magnetic Clouds and Interplanetary Coronal Mass Ejections which Cause Intense Geomagnetic Storms Chin-Chun Wu1, *, Natchimuthuk Gopalswamy 2, Ronld Paul Lepping 3, and Seiji Yashiro 2, 4 1 Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC, USA 2 Solar Physics Laboratory, Solar System Exploration Division, NASA/GSFC, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA 3 Heliosphysics Science Division, NASA/GSFC, Greenbelt, Maryland, USA 4 The Physics Department, The Catholic University of America, Washington, DC, USA Received 18 March 2012, accepted 26 September 2012 ABSTRACT We present the results of a statistical data analysis of the geo-effectiveness of non-magnetic-cloud interplanetary coronal mass ejections (ICMEs) and compare them with those of magnetic-cloud (MC) interplanetary coronal mass ejections observed during solar cycle 23. (The term ICME as used here will refer to a non-MC ICME.) The starting point of this investigation is the set of intense geomagnetic storms (Dstmin ≤ -100 nT) of solar cycle 23 between 1996 and 2005. We also compare the solar source locations of the ICMEs with those of the MCs. The source locations of the solar disturbances are, on average, closer to the Sun-Earth line for the MCs than for the ICMEs. There is an anomaly for the location of the related solar sources: no event came from the region between the solar equator plane and 10°S (south) of that plane. The primary results are listed as follows. The average duration of these MCs is slightly longer (~7%) than that of ICMEs. -

Observation of an Evolving Magnetic Flux Rope Before and During a Solar Eruption

ARTICLE Received 31 Oct 2011 | Accepted 16 Feb 2012 | Published 20 Mar 2012 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1753 Observation of an evolving magnetic flux rope before and during a solar eruption Jie Zhang1, Xin Cheng1,2 & Ming-de Ding2 Explosive energy release is a common phenomenon occurring in magnetized plasma systems ranging from laboratories, Earth’s magnetosphere, the solar corona and astrophysical environments. Its physical explanation is usually attributed to magnetic reconnection in a thin current sheet. Here we report the important role of magnetic flux rope structure, a volumetric current channel, in producing explosive events. The flux rope is observed as a hot channel before and during a solar eruption from the Atmospheric Imaging Assembly telescope on board the Solar Dynamic Observatory. It initially appears as a twisted and writhed sigmoidal structure with a temperature as high as 10 MK, and then transforms toward a semi-circular shape during a slow-rise phase, which is followed by fast acceleration and onset of a flare. The observations suggest that the instability of the magnetic flux rope triggers the eruption, thus making a major addition to the traditional magnetic-reconnection paradigm. 1 School of Physics, Astronomy and Computational Sciences, George Mason University, 4400 University Drive, MSN 6A2, Fairfax, Virginia 22030, USA. 2 Department of Astronomy, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to J.Z. (email: [email protected]). NATURE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:747 | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1753 | www.nature.com/naturecommunications © 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited. All rights reserved. ARTICLE NatUre cOMMUNicatiONS | DOI: 10.1038/ncomms1753 n contrast to a thin current sheet structure, a magnetic flux rope rope11.